Change in Rural Karnataka Over the Last Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shake Hands and Make up 0

NEWSBEAT Shake hands and make up Chief minister Ramakrishna Hegde and the dissidents, led by H. D. Deve Gowda, have called a truce. But, given the belligerence of both sides, how long will it last? ast week, Sunday wondered In fact, there is a persistent suspicion whether Ajit Singh, the new that in spite of the Express'reference to young president of the Janata central government sources, the trans Party would accept Ramak cript came from Bangalore. Who stands rishna Hegde’s resignation. to gain the most from exposing a nexus This week, the answer is in. Yet anotherbetween Ajit Singh and Deve Gowda ofL Hegde’s resignation dramas has ask the cynics. Obviously, it is the chief drawn curtains prematurely. It was up minister. staged by a bigger story: the transcript The chief minister, of course, loudly of the phone conversation between Ajit denied his involvement. In fact, he tried Singh and Janata rebel leader H.D. Deve to give yet another tape episode Gowda, that appeared in Ihe Indian the political. mileage he had ex Express on 10 July. tracted from the Veerappa Moily -Byre The timing was devastating enough to Gowda tapes. This time hewasmuch look suspiciously like a deliberate plant. more subdued. But he is still the injured It came on the eve of Hegde’s departure innocent. “You know, even my phone is to Delhi for the crucial Janata Parliamen tapped, ” he said in Bangalore. So will he Hegde being welcomed by loyalists on his tary Board meeting. Worse. It was not lodge a protest with the central return from Delhi: triumphant carried along with the full text of government? “I have done it so many Hegde’s conditional resignation to Ajit times, what is the use?” he replied. -

Cm of Karnataka List Pdf

Cm of karnataka list pdf Continue CHIEF MINISTERS OF KARNATAKA Since 1947 SL.NO. Date from date to 1. Sri K.CHENGALARAY REDDY 25-10-1947 30-03-1952 2. Sri K.HANUMANTAYA 30-03-1952 19-08-1956 3. Sri KADIDAL MANJAPPA 19-08-1956 31-10-1956 4. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 01-11-1956 16-05-1958 5. Sri B.D. JATTI 16-05-1958 09-03-1962 6. Sri S.R.Kanthi 14-03-1962 20-06-1962 7. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 21-06-1962 28-05-1968 8. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 29-05-1968 18-03-1971 9. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 19-03-1971 20-03-1972 10. Sri D.DEVRAJ URS 20-03-1972 31-12-1977 11. RULE PRESIDENTS 31-12-1977 28-02-1978 12. Sri D.DEVARAJ URS 28-02-1978 07-01-1980 13. Sri R.GUNDU RAO 12-01-1980 06-01- 1983 14. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 10-01-1983 29-12-1984 15. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 08-03-1985 13-02-1986 16. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 16-02-1986 10-08-1988 17. Sri S.R.BOOMMAI 13-08-1988 21-04-1989 18. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 21-04-1989 30-11-1989 19. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 30-11-1989 10-10-1990 20. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 10-10-1990 17-10-1990 21. Sri S.BANGARAPPA 17-10-1990 19-11-1992 22. Sri VEERAPPA MOILY 19-11-1992 11-12-1994 23. Sri H.D. DEVEGOVDA 11-12-1994 31-05-1996 24. Sri J.H.PATEL 31-05-1996 07-10-1999 25. -

1 to 15 May, 2008

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIVVV (((111 tttooo 111555 MMMaaayyy,,, 222000000888))) NNNooo... 999 AGRICULTURE -(INDIA) 1 KADAMBOT SIDDIQUE Challenge and opportunity in agriculture. HINDU, 2008(2.5.2008) ** Agriculture-(India). -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COTTON 2 DESAI, Sachiketa Taking the organic route. BUSINESS INDIA, No.782, 2008(9.3.2008): P.110-111 Examines India's emergence as world's top producer of Organic cotton. ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Cotton; Organic farming -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-SUGARCANE 3 ANTONY, M.J. Bitter battles in the sugar fields. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on lack of rationalisation of sugarcane prices and coordinated policy. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Sugarcane. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-TEA 4 SATYA SUNDARAM, I Tea: Facing rough weather. FACTS FOR YOU, V.28(No.5), 2008(February): P.7-9 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Tea. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-VEGETABLES 5 RAHUL JAYARAM Brinjal battles. TELEGRAPH, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on controversies related with genetically modified brinjals. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Vegetables. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 6 GOSWAMI, Anupam Credit for a waiver. BUSINESS INDIA, No.784, 2008(6.4.2008): P.42-44 Analyses the consequences of farm loan waiver scheme announced in the current budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. 7 JOSHI, Rakesh Notes for votes. BUSINESS INDIA, No.783, 2008(23.3.2008): P.98-104 Highlights the loan waiver package offered to farmers in the present budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA) 8 Prospects of agriculture. ASSAM TRIBUNE, 2008(7.5.2008) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Policy-(India). 9 SHARMA, Manish Optimise the food-energy mix. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2008(7.5.2008) Emphasises the need for comprehensive agriculture sector reforms. -

3. Modern Indian History

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION IV SEMESTER B.A HISTORY: COMPLEMENTARY MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT DAY: HIS4C01 SELECTED THEMES IN CONTEMPORARY INDIA (2014 Admission onwards) Multiple-Choice Questions and Answers Prepared by Dr.N.PADMANABHAN Associate Professor&Head P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi P.O.Payangadi-RS-670358 Dt.Kannur-Kerala 1. The Constitution of ....................is the largest written liberal democratic constitution of the world. 1 a) India b) America c) Pakistan d) Afghanistan 2. The Constitution of ...................provides for a mixture of federalism and Unitarianism, and flexibility and with rigidity. a) Afghanistan b) America c) Pakistan d) India 3. since its inauguration on 26th January.............. , the Constitution India has been successfully guiding the path and progress of India. a)1905 b)1915 c)1930 d) 1950 4. Indian Constitution consists of ................ Articles divided into 22 Parts with 12 Schedules and 94 constitutional amendments. a)295 b)305 c)388 d) 395 5.The Constitution of India indeed much bigger than the US Constitution which has only 7 Articles and the ..................Constitution with its 89 Articles. a) French b) Dutch c) Pakistan d)Afghanistan 6. The constitution of India became fully operational with effect from 26th January.......................... a)1905 b)1935 c)1947 d) 1950 7. Although, right from the beginning the Indian Constitution fully reflected the spirit of democratic socialism, it was only in ................. that the Preamble was amended to include the term ‘Socialism’. a)1936 b)1946 c)1956 d) 1976 8.India has an elected head of state (President of India) who wields power for a fixed term of .................. -

(Ph. D. Thesis) March, 1990 Takako Hirose

THE SINGLE DOMINANT PARTY SYSTEM AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT: CASE STUDIES OF INDIA AND JAPAN (Ph. D. Thesis) March, 1990 Takako Hirose ABSTRACT This is an attempt to compare the processes of political development in India and Japan. The two states have been chosen because of some common features: these two Asian countries have preserved their own cultures despite certain degrees of modernisation; both have maintained a system of parliamentary democracy based on free electoral competition and universal franchise; both political systems are characterised by the prevalence of a single dominant party system. The primary objective of this analysis is to test the relevance of Western theories of political development. Three hypotheses have been formulated: on the relationship between economic growth and social modernisation on the one hand and political development on the other; on the establishment of a "nation-state" as a prerequisite for political development; and on the relationship between political stability and political development. For the purpose of testing these hypotheses, the two countries serve as good models because of their vastly different socio-economic conditions: the different levels of modernisation and economic growth; the homogeneity- heterogeneity dichotomy; and the frequency of political conflict. In conclusion, Japan is an apoliticised society in consequence of the imbalance between its political and economic development. By contrast, the Indian political system is characterised by an ever-increasing demand for - 2 - participation, with which current levels of institutionalisation cannot keep pace. The respective single dominant parties have thus played opposing roles, i.e. of apoliticising society in the case of Japan while encouraging participation in that of India. -

Morarji Desai - My True Friend

Morarji Desai - my true friend I was first introduced to Morarji Desai in 1975 when senior leaders were finding it difficult to bring him and Jayaprakash Narayan on the same wave length of thinking and pushed me in the front to dare to talk to both. As I have already described in my earlier article, if it were not for my audacity in bringing JP and Morarji together, the June 25th 1975 historic Ramlila Ground meeting in Delhi (which Mrs. Gandhi used as an excuse to declare Emergency), would never have taken place. The Emergency was originally scheduled for June 22nd when JP was to address the rally, but his Patna-Delhi Indian Airlines flight got cancelled, and so Mrs.Gandhi postponed the decision. She wanted to use JP's speech as an excuse. It is a wonder to me that had I not succeeded to bringing the two together on June 25th, and the meeting thus cancelled, would the declaration of Emergency been further postponed, or even Mrs.Gandhi changed her mind about the idea itself with a little more time to think about it? My Next meeting with Morarji Desai was a stormy one. It was a meeting demanded by Morarji to give me a lecture. It was also meeting that became a turning point because after that Morarji and I became very close. The General Elections to Lok Sabha were declared on January 18, 1977 when I was abroad, having escaped again after a dramatic appearance on the floor of Parliament despite an MISA arrest warrant and the highest reward on my head for my capture. -

Questions & Solutions

ENGLISH NDA-2012 EXAMINATION CAREER POINT QUESTIONS & SOLUTIONS PART – A Direction (For the next 08 items which follow) : Read the following 02 passages and answer the questions that following each passage : Passage – 1 There was a farewell ceremony on here day at school, to which my parents and I were invited. It was a touching ceremony in a solemn kind of way. The City Corporation sent a representative and so did the two main political parties. There were many speeches and my grandmother was garlanded by a girl from every class. Then the haed-girl, a particular favourite of hers, unveiled the farewell present the girls had bought for her by subscription. It was a large marble model of the Taj Mahal; it had a bulb inside and could be lit up like a table lamp. My grandmother made a speech too, but she couldn't finish it properly, for she began to cry before she got to the end of it and to stop to wipe away her tears. I turned away when she began dabbing at her eyes with a huge green handkerchief and discovered, to my surprise, that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their green hankerchief and discovered, to my surprise. that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their eyes too. I was very jealous. I remember. I had always taken it for granted that it was my own special right to love her ; I did know how to cope with the discovery that my right had been infringed by a whole school. -

Jayaprakash Narayan: an Idealist Betrayed

Jayaprakash Narayan: An Idealist Betrayed M.G. DEVASAHAYAM Jayaprakash Narayan addressing a public meeting at Sitabdiara during a visit to his village on November 5, 1977. Photo: The Hindu Archives. The imposition of the Emergency in June 1975 by Indira Gandhi led to a general uprising across the country under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly known as JP. It also brought together strange bedfellows—the socialists and the Jan Sangh, the political face of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). In this personal epitaph on Jayaprakash Narayan, former civil servant M.G. Devasahayam, who was "the only person who had unrestricted access" to the late JP when he was prisoner during the Emergency, explains how the JP movement fizzled out due to what he terms the "betrayal of the RSS". Prelude The150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi commenced on October 2, 2018 with all solemnity and is being celebrated across the country. October 2 has become an iconic date known to even kindergarten kids. October 11 is the 116th birth anniversary of Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly known as JP. If Mahatma Gandhi is the architect of India’s first freedom in 1947, which was extinguished by Congress supremo Indira Gandhi on 25/26 June, 1975, it was JP who got us our second freedom after defeating Emergency in 1977. While Gandhiji won it from a tottering alien rule, JP had to take on and defeat the might of an entrenched domestic despot with vast resources and armed with draconian Emergency powers, reminiscent of Stalinist regime. In gratitude, common people called him the Second Mahatma. -

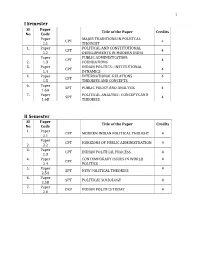

I Semester II Semester

1 I Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code Paper MAJOR TRADITIONS IN POLIITCAL CPT 4 1.1 THOUGHT 1. Paper POLITICAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.2 DEVELOPMENTS IN MODERN INDIA Paper PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION: CPT 4 2. 1.3 FOUNDATIONS 3. Paper INDIAN POLITICS : INSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.4 DYNAMICS 4. Paper INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS : 4 CPT 1.5 THEORIES AND CONCEPTS 6. Paper SPT PUBLIC POLICY AND ANALYSIS 4 1.6A 7. Paper POLITICAL ANALYSIS : CONCEPTS AND SPT 4 1.6B THEORIES II Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper CPT MODERN INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT 4 2.1 Paper CPT HORIZONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION 4 2. 2.2 3. Paper CPT INDIAN POLITICAL PROCESS 4 2.3 4. Paper CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN WORLD 4 CPT 2.4 POLITICS 5. Paper 4 SPT NEW POLITICAL THEORIES 2.5A 6. Paper SPT POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY 4 2.5B 7. Paper OEP INDIAN POLITICS TODAY 4 2.6 III Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper DEBATES IN CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL 4 CPT 3.1 THEORY Paper CPT PUBLIC GOVERNANCE 4 2. 3.2 3. Paper DIMENSIONS OF DEVELOPMENT IN CPT 4 3.3 KARNATAKA 4. Paper 4 CPT RESEARCH METHODS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE 3.4 5. Paper 4 SPT RURAL GOVERNANCE IN INDIA 3.5A 6. Paper SPT GLOBAL CHALLENGES 4 3.5B 7. Paper OEP HUMAN RIGHTS : ISSUES AND CHALLENGES 4 3.6 IV Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper MODERN WESTERN POLITICAL CPT 4 4.1 THOUGHT Paper GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS IN CPT 4 2. -

Lotus Blooms in Karnataka

https://www.facebook.com/Kamal.Sandesh/ www.kamalsandesh.org @kamalsandeshbjp STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN INDIA AND RUSSIA IS IMPORTANT FOR GLOBAL PEACE & STABILITY Vol. 13, No. 11 01-15 June, 2018 (Fortnightly) `20 kaRNATaka ASSEMBLY ELECTION RESULTS 2018 LOTUS BLOOMS in Karnataka THIRD NORTH EAST DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE AMID TMC VIOLENCE, BJP EMERGES ‘All yoJANAS TO BENEFIT PEOPLE 1 I KAMAL SANDESH(NEDA) I 01-15CONC JULY,LAVE, 2017GUWAHATI AS SECOND LARGEST paRTY 01-15 JUNE,AT THE 2018 END I KAMALOF SOC SANDESHIETy’ I 1 BJP National President Shri Amit Shah along with other senior BJP National President Shri Amit Shah addressing the Party leaders welcoming PM Shri Narendra Modi to BJP National Karyakartas at BJP National Headquarters after Karnataka Headquarters after Karnataka verdict verdict PM Shri Narendra Modi flanked by BJP National President Shri Amit Shah & Members of BJP Parliamentary Board in a meeting at BJP HQ, New Delhi after Karnataka verdict BJP National President Shri Amit Shah interacting with BJP Shri Amit Shah addressing the 3rd Conclave of North East National Office Bearers, State Presidents, In-Charge of States and Democratic Alliance (NEDA) in Guwahati, Assam State Organizational General Secretaries on party organizational activities at BJP HQ, New Delhi 2 I KAMAL SANDESH I 01-15 JUNE, 2018 Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Mukesh Kumar Phone +91(11) 23381428 FAX +91(11) 23387887 LOTUS BLOOMS IN KARNATaka E-mail The Election Commission declared the Karnataka Assembly Election [email protected] Results on 15 May, 2018. -

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics LESSON PLAN FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR: 2015-16 Programme: Arts Course/Paper Name: Principles of Macro Economics Semester: II semester Class: B.A Sl. Unit Unit to be covered as Date Unit related events / No prescribed by the components for effective university From To curriculum delivery 01. I An Overview of 11/01/2016 10/02/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Macroeconomics : Assignment, Seminar by Macroeconomics: Meaning, Students, Group Types and Scope - discussion. Importance and Limitations - Basic Concepts of Macroeconomics, Stocks, Flow and Equilibrium - National Income: Meaning and Importance - Concepts - GDP, GNP, NDP, NNP, NI, PI, DPI and Per capita Income - Circular Flow of Income 02. II Classical Theory of 11/02/2016 02/03/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Employment: Basic Assignment, Seminar by Assumptions of Classical Students, Group Theory - Classical Theory discussion. of Employment - Say’s Law of Market - Wage - Price Flexibility (Pigou’s Version) - Saving and Investment Equality - Evaluation of the Classical Theory of Employment 03. III Keynesian Theory: 03/03/2016 01/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Concepts of Effective Assignment, Seminar by Demand and its Students, Group Determinants. Equilibrium discussion. Level of Income and Employment. Consumption Function: Psychological Law of Consumption, Factors Affecting Consumption Function. Investment Function: Factors Affecting Investment Function. Multipiler - Evaluation of the Keynesian Theory of Employment. 04. IV Inflation, Deflation and 02/04/2016 29/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Business Cycle: Inflation: Assignment, Seminar by Meaning and Types - Students, Group Causes and Effects of discussion. -

Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214

V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Veerashaiva Vidyavardhak Sangha‘s SHREE KHASGATESH COLLEGE OF ARTS AND COMMERCE, TALIKOTI – 586214 DIST. VIJAYAPUR KARNATAKA (Affiliated to Rani Channamma University, Belagavi) Website:www.skctalikoti.com Email:[email protected] Phone No./Fax : 08356-266310 Cell : 9740220318 Self Study Report Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council For 3rd Cycle of Accreditation January, 2016 SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Shri. Khasgata Shivayogigalu SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Shri. Ma. Ni. Pra. Virakta Mahaswamigalu SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 CONTENTS Sl. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Covering letter 01 2 Preface and Executive Summary : The SWOC Analysis 02-13 3 Profile of the Institution : Institutional data 14-22 4 Criteria-Wise Analytical Report Criterion – I – Curricular Aspects 23-37 Criterion – II – Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 38-75 Criterion – III – Research, Consultancy and Extension 76-101 Criterion – IV – Infrastructure and Learning Resources 102-117 Criterion – V – Student Support and Progression 118-142 Criterion – VI -- Governance, Leadership and 143-166 Management Criterion – VII - Innovations and Best Practices 167-176 5 Evaluative Report of the Departments 177-234 6 Post Accreditation Initiatives 235-236 7 Compliance Report 237 8 Declaration by the Head of the Institution 238 9 Enclosures 239-287 SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation….