JCC NUCLEAR ARMS RACE: INDIA BACKGROUND GUIDE & Letters from the Directors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of 33 Rd Meeting of the Executive

bl ~(I fctsg fch"l I~~ I TRIPURA UNIVERSITY ~<f"i fU1 '1~1 VSuryamaninagar, ~/Tripura - 799022 F· .. ruiRE01E·c/33:AiiO t9• ....................................................... Date: 30th August, 2019 1 Proceedings of the 33rd Meeting of Executive Council held on 30 h August, 2019 at 11 :30 AM in the Council Hall, Administrative Building, Tripura University. Members present in the meeting: I. Prof. V.L. Dharurkar, Vice-Chancellor, T.U. - Ex-officio Chairman 2. Prof. S. Sinha, Senior-most Professor, T.U. - Member 3. Prof. C.B. Maju1nder -Member Dean, Faculty of Arts & Commerce, T.U. 4. Prof. S. Banik, Dean, Faculty of Science, T.U. - Member 5. Prof. T.V. Kattimani - Member (Visitor's Nominee) Vice-Chancellor, IGNTU, Amarkantak 6. Prof. Khemsingh Daheriya - Member (Visitor's Nominee) Department of Hindi & Dean, Faculty of Humanities and Philosophy, IGNTU, Amarkantak (MP) 7. Prof. N. Lokendra Singh - Member (Visitor's Nominee) Head, Department of History, Manipur University, Imphal 8. Director, Higher Education, Govt. of Tripura - Member (Nominee of the Secretary, Higher Education) 9. Prof. B.K. Datta, Registrar (i/c), T.U . - Ex-officio Secretary At the outset, the Hon'ble Vice-Chancellor welcomed all members to the 33rd \1eeting of Executive Council, T.U. He specially thanked Visitor's Nominees for their kind presence in the meeting. The membi;rs, who attended the meeting first time, were felicitated by books and mementos. Before starting the day's business, the Hon'ble Vice-Chancellor ap raised the members about the verdict of the litigation filed against Tripura University w.r.t. app intment of Registrar and validity of the 32nd Meeting of the Executive Council, which was in favour of the University. -

Magazine Can Be Printed in Whole Or Part Without the Written Permission of the Publisher

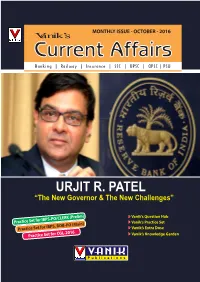

MONTHLY ISSUE - OCTOBER - 2016 CurrVanik’s ent Affairs Banking | Railway | Insurance | SSC | UPSC | OPSC | PSU URJIT R. PATEL “The New Governor & The New Challenges” Vanik’s Question Hub -PO/CLERK (Prelim) Practice Set for IBPS Vanik’s Practice Set -PO (Main) Practice Set for IBPS, BOB Vanik’s Extra Dose GL-2016 Practice Set for C Vanik’s Knowledge Garden P u b l i c a t i o n s VANIK'S PAGE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORTS OF INDIA NAME OF THE AIRPORT CITY STATE Rajiv Gandhi International Airport Hyderabad Telangana Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International Airport Amristar Punjab Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport Guwaha ti Assam Biju Patnaik International Airport Bhubaneshwar Odisha Gaya Airport Gaya Bihar Indira Gandhi International Airport New Delhi Delhi Andaman and Nicobar Veer Savarkar International Airport Port Blair Islands Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport Ahmedabad Gujarat Kempegowda International Airport Bengaluru Karnatak a Mangalore Airport Mangalore Karnatak a Cochin International Airport Kochi Kerala Calicut International Airport Kozhikode Kerala Trivandrum International Airport Thiruvananthapuram Kerala Raja Bhoj Airport Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Devi Ahilyabai Holkar Airport Indore Madhya Pradesh Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport Mumbai Maharashtr a Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport Nagpur Maharashtr a Pune Airport Pune Maharashtra Zaruki International Airport Shillong Meghalay a Jaipur International Airport Jaipur Rajasthan Chennai International Airport Chennai Tamil Nadu Civil Aerodrome Coimbator e Tamil Nadu Tiruchirapalli International Airport Tiruchirappalli Tamil Nadu Chaudhary Charan Singh Airport Lucknow Uttar Pradesh Lal Bahadur Shastri International Airport Varanasi Uttar Pradesh Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose International Airport Kolkata West Bengal Message from Director Vanik Publications EDITOR Dear Students, Mr. -

Politics of Coalition in India

Journal of Power, Politics & Governance March 2014, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 01–11 ISSN: 2372-4919 (Print), 2372-4927 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Politics of Coalition in India Farooq Ahmad Malik1 and Bilal Ahmad Malik2 Abstract The paper wants to highlight the evolution of coalition governments in india. The evaluation of coalition politics and an analysis of how far coalition remains dynamic yet stable. How difficult it is to make policy decisions when coalition of ideologies forms the government. More often coalitions are formed to prevent a common enemy from the government and capturing the power. Equally interesting is the fact a coalition devoid of ideological mornings survives till the enemy is humbled. While making political adjustments, principles may have to be set aside and in this process ideology becomes the first victim. Once the euphoria victory is over, differences come to the surface and the structure collapses like a pack of cards. On the grounds of research, facts and history one has to acknowledge india lives in politics of coalition. Keywords: india, government, coalition, withdrawal, ideology, partner, alliance, politics, union Introduction Coalition is a phenomenon of a multi-party government where a number of minority parties join hands for the purpose of running the government which is otherwise not possible. A coalition is formed when many groups come into common terms with each other and define a common programme or agenda on which they work. A coalition government always remains in pulls and pressures particularly in a multinational country like india. -

Shake Hands and Make up 0

NEWSBEAT Shake hands and make up Chief minister Ramakrishna Hegde and the dissidents, led by H. D. Deve Gowda, have called a truce. But, given the belligerence of both sides, how long will it last? ast week, Sunday wondered In fact, there is a persistent suspicion whether Ajit Singh, the new that in spite of the Express'reference to young president of the Janata central government sources, the trans Party would accept Ramak cript came from Bangalore. Who stands rishna Hegde’s resignation. to gain the most from exposing a nexus This week, the answer is in. Yet anotherbetween Ajit Singh and Deve Gowda ofL Hegde’s resignation dramas has ask the cynics. Obviously, it is the chief drawn curtains prematurely. It was up minister. staged by a bigger story: the transcript The chief minister, of course, loudly of the phone conversation between Ajit denied his involvement. In fact, he tried Singh and Janata rebel leader H.D. Deve to give yet another tape episode Gowda, that appeared in Ihe Indian the political. mileage he had ex Express on 10 July. tracted from the Veerappa Moily -Byre The timing was devastating enough to Gowda tapes. This time hewasmuch look suspiciously like a deliberate plant. more subdued. But he is still the injured It came on the eve of Hegde’s departure innocent. “You know, even my phone is to Delhi for the crucial Janata Parliamen tapped, ” he said in Bangalore. So will he Hegde being welcomed by loyalists on his tary Board meeting. Worse. It was not lodge a protest with the central return from Delhi: triumphant carried along with the full text of government? “I have done it so many Hegde’s conditional resignation to Ajit times, what is the use?” he replied. -

Cm of Karnataka List Pdf

Cm of karnataka list pdf Continue CHIEF MINISTERS OF KARNATAKA Since 1947 SL.NO. Date from date to 1. Sri K.CHENGALARAY REDDY 25-10-1947 30-03-1952 2. Sri K.HANUMANTAYA 30-03-1952 19-08-1956 3. Sri KADIDAL MANJAPPA 19-08-1956 31-10-1956 4. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 01-11-1956 16-05-1958 5. Sri B.D. JATTI 16-05-1958 09-03-1962 6. Sri S.R.Kanthi 14-03-1962 20-06-1962 7. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 21-06-1962 28-05-1968 8. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 29-05-1968 18-03-1971 9. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 19-03-1971 20-03-1972 10. Sri D.DEVRAJ URS 20-03-1972 31-12-1977 11. RULE PRESIDENTS 31-12-1977 28-02-1978 12. Sri D.DEVARAJ URS 28-02-1978 07-01-1980 13. Sri R.GUNDU RAO 12-01-1980 06-01- 1983 14. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 10-01-1983 29-12-1984 15. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 08-03-1985 13-02-1986 16. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 16-02-1986 10-08-1988 17. Sri S.R.BOOMMAI 13-08-1988 21-04-1989 18. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 21-04-1989 30-11-1989 19. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 30-11-1989 10-10-1990 20. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 10-10-1990 17-10-1990 21. Sri S.BANGARAPPA 17-10-1990 19-11-1992 22. Sri VEERAPPA MOILY 19-11-1992 11-12-1994 23. Sri H.D. DEVEGOVDA 11-12-1994 31-05-1996 24. Sri J.H.PATEL 31-05-1996 07-10-1999 25. -

Important Days in February

INSIDE STORY IMPORTANT DAYS IN JANUARY January 09 NRI Day (Pravasi Bharatiya Divas) CAA-2019 3 Miss Universe and Miss World-2019 4 January 10 World Hindi Day First Chief of Defence Staff 5 January 12 National Youth Day Sports Person of the Year-2019 5 January 15 Indian Army Day National News 6 January 24 National Girl Child Day International News 11 January 25 National Voters Day 500+ G.K. One Liner Questions 15 January 27 World Leprosy Day (Every last GS Special 31 Sunday) Awards 32 New Appointments 36 IMPORTANT DAYS IN FEBRUARY Sports 40 February 02 World Wetlands Day Banking & Financial Awareness 45 February 04 World Cancer Day Defence & Technology 47 February 10 National De-worming Day Study Notes 49 February 12 National Productivity Day Tricky Questions 59 February 13 World Radio Day IBPS Clerk (Mains) - Practice Test Paper 70 February 20 World Day of Social Justice SSC CGL (Tier-I) - Practice Test Paper 95 SSC CHSL (Tier-I) - Practice Test Paper 104 February 21 International Mother Language IBPS SO AFO (Mains) - Memory Based Paper 110 Day February 28 National Science Day IMPORTANT RATES (31-12-2019) Repo Rate 5.15% Reverse Repo Rate 4.90% Marginal Standing Facility Rate 5.40% Statutory Liquidity Ratio 18.50% Cash Reserve Ratio 4% Bank Rate 5.40% New Batches Starting for SSC CHSL : 13th & 16th Jan 2020 RBI ASSISTANT : 13th Jan. 2020 For Admission Contact : IBT Nearest Center or Call - 9696960029 ...for abundant practice download Makemyexam app IBT: How much time did you use to Name: Karan Bhagat devote for the preparation of the exam? Fathers Name: Haqeeqat Rai Karan: Sir, I never made a hard and fast Education: B.Sc (Non-Medical) rule for myself to study for a fixed no. -

The Fall-Out of a New Political Regime in India

ASIEN, (Juli 1998) 68, S. 5-20 The Fall-out of a New Political Regime in India Dietmar Rothermund Eine "rechte" Koalition geführt von der Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) hat das "Congress System" abgelöst, das darin bestand, daß sich eine "Zentrumspartei" durch die Polarisation von rechter und linker Opposition an der Macht erhielt. Wahlallianzen der BJP haben regionalen Parteien zu Sitzen verholfen, die früher im Schatten der nationalen Parteien standen. So verschaffte sich die BJP Koali- tionspartner. Die Wähler haben der BJP kein überzeugendes Mandat erteilt, dennoch führte sie ihr Programm durch, zu dem die Atomtests gehörten, die dann in der Bevölkerung breite Zustimmung fanden. Die BJP fühlt sich so dazu ermutigt, eine sehr selbstbewußte Außenpolitik zu betreiben. Dazu gehört auch die Betonung der wirtschaftlichen Eigenständigkeit (Swadeshi). Der am 1.6.1998 vorgelegte Staatshaushalt zeigt kein Entgegenkommen gegenüber ausländischen Investoren. Den angekündigten amerikanischen Sanktionen wurde mit einer Rücklage begegnet und die Verteidigungsausgaben um 14 Prozent erhöht. The formation of a government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is certainly a new departure in Indian politics. All previous governments were formed either by the Indian National Congress or by politicians who had earlier belonged to that party. The BJP and its precursor the Bharatiya Jan Sangh had always been in the opposition with the exception of the brief interlude of the Janata government (1977- 1980) in which the present Prime Minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, held the post of Minister of External Affairs. The BJP has consistently stood for Hindu nationalism and has attacked the secularism of the Congress as a spurious ideology which should be replaced by genuine secularism. -

Leader of the House F

LEADER OF THE HOUSE F. No. RS. 17/5/2005-R & L © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLISHED BY SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AND NEW DELHI PRINTED BY MANAGER, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002. PREFACE This booklet is part of the Rajya Sabha Practice and Procedure Series which seeks to describe, in brief, the importance, duties and functions of the Leader of the House. The booklet is intended to serve as a handy guide for ready reference. The information contained in it is synoptic and not exhaustive. New Delhi DR. YOGENDRA NARAIN February, 2005 Secretary-General THE LEADER OF THE HOUSE Leader of the House in Rajya Sabha Importance of the Office Rule 2(1) of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) defines There are quite a few functionaries in Parliament who the Leader of Rajya Sabha as follows: render members’ participation in debates more real, effective and meaningful. One of them is the 'Leader of "Leader of the Council" means the Prime Minister, the House'. The Leader of the House is an important if he is a member of the Council, or a Minister who parliamentary functionary who exercises direct influence is a member of the Council and is nominated by the on the course of parliamentary business. Prime Minister to function as the Leader of the Council. Origin of Office in England In Rajya Sabha, the following members have served In England, one of the members of the Government, as the Leaders of the House since 1952: who is primarily responsible to the Prime Minister for the arrangement of the government business in the Name Period House of Commons, is known as the Leader of the House. -

Analysis of Zirconium and Nickel Based Alloys and Zirconium Oxides

NET318_proof ■ 22 February 2017 ■ 1/7 Nuclear Engineering and Technology xxx (2017) 1e7 Available online at ScienceDirect 65 66 1 67 2 Nuclear Engineering and Technology 68 3 69 4 70 5 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/net 71 6 72 7 73 8 74 9 Original Article 75 10 76 11 Analysis of Zirconium and Nickel Based Alloys and 77 12 78 13 Zirconium Oxides by Relative and Internal 79 14 80 15 81 16 Monostandard Neutron Activation Analysis 82 17 83 18 Q1 Methods 84 19 85 20 * 86 21 a b, a,1 Q15 Q2Amol D. Shinde , R. Acharya , and A.V.R. Reddy 87 22 88 Q3 a Analytical Chemistry Division, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Trombay, Mumbai 400 085, India 23 89 b Radiochemistry Division, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Trombay, Mumbai 400 085, India 24 90 25 91 26 92 article info abstract 27 93 28 94 29 Article history: Background: The chemical characterization of metallic alloys and oxides is conventionally 95 30 Received 9 March 2016 carried out by wet chemical analytical methods and/or instrumental methods. Instru- 96 31 Received in revised form mental neutron activation analysis (INAA) is capable of analyzing samples nondestruc- 97 32 1 August 2016 tively. As a part of a chemical quality control exercise, Zircaloys 2 and 4, nimonic alloy, and 98 33 99 34 Accepted 19 September 2016 zirconium oxide samples were analyzed by two INAA methods. The samples of alloys and Available online xxx oxides were also analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy 100 35 101 (ICP-OES) and direct current Arc OES methods, respectively, for quality assurance pur- 36 102 Keywords: poses. -

WEDNESDAY, the 22ND JULY, 1998 (The Rajya Sabha Met in The

WEDNESDAY, THE 22ND JULY, 1998 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11.00 a.m.) 1. STATEMENT BY MINISTER CORRECTING ANSWER TO QUESTION Shri L. K. Advani (Minister of Home Affairs) laid on the Table a Statement (in English and Hindi) correcting the reply given in Rajya Sabha on the 3rd June, 1998 to Unstarred Question 803 regarding Technicians in ITBP. 2. PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE Shri P. R. Kumaramangalam (Minister of Power) laid on the Table a copy (in English and Hindi) of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of India (Ministry of Power) and National Hydro Electric Power Corporation Limited, for the year 1998-99. Shri Kashiram Rana (Minister of Textiles) laid on the Table- I. (1) A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers, under sub-section (1) of section 619A of the Companies Act, 1956:- (i) Annual Report and Accounts of the Jute Corporation of India Limited, Calcutta, for the year 1996-97, together with the Auditors' Report on the Accounts and the comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India thereon. (ii) Review by Government on the working of the above Corporation. (2) Statement (in English and Hindi) giving reasons for the delay in laying the papers mentioned at (1) above. II. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers:- (i) Annual Report and Accounts of the Indian Jute Industries' Research Association, Calcutta, for the year 1996-97, together with the Auditors' Report on the Accounts. (ii) Review by Government on the working of the above Association. -

3. Modern Indian History

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION IV SEMESTER B.A HISTORY: COMPLEMENTARY MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT DAY: HIS4C01 SELECTED THEMES IN CONTEMPORARY INDIA (2014 Admission onwards) Multiple-Choice Questions and Answers Prepared by Dr.N.PADMANABHAN Associate Professor&Head P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi P.O.Payangadi-RS-670358 Dt.Kannur-Kerala 1. The Constitution of ....................is the largest written liberal democratic constitution of the world. 1 a) India b) America c) Pakistan d) Afghanistan 2. The Constitution of ...................provides for a mixture of federalism and Unitarianism, and flexibility and with rigidity. a) Afghanistan b) America c) Pakistan d) India 3. since its inauguration on 26th January.............. , the Constitution India has been successfully guiding the path and progress of India. a)1905 b)1915 c)1930 d) 1950 4. Indian Constitution consists of ................ Articles divided into 22 Parts with 12 Schedules and 94 constitutional amendments. a)295 b)305 c)388 d) 395 5.The Constitution of India indeed much bigger than the US Constitution which has only 7 Articles and the ..................Constitution with its 89 Articles. a) French b) Dutch c) Pakistan d)Afghanistan 6. The constitution of India became fully operational with effect from 26th January.......................... a)1905 b)1935 c)1947 d) 1950 7. Although, right from the beginning the Indian Constitution fully reflected the spirit of democratic socialism, it was only in ................. that the Preamble was amended to include the term ‘Socialism’. a)1936 b)1946 c)1956 d) 1976 8.India has an elected head of state (President of India) who wields power for a fixed term of .................. -

Final Shareholders List

Folio DP ID Client ID First Named Shareholder Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Address Line 4 PIN Shares 118792 GOVIND MOHANLAL BHATIA P O BOX NO 755 SHARJAH U A E 000000 3780 000290 AMRIT LAL MADAN 105,PARKS ROAD, DENVILLE, N.J.07834 TEL:973-627-3967 000000 435 162518 RADHA MANUCHA 2,TIPPETT ROAD, TORONTO ONTARIO, CANADA M3H 2V2 000000 1867 001495 GEORGE A TERRETT C/O BURMA OIL CO (1954) LTD 604,MERCHAN P B -1049.RANGOON 000000 210 188740 RAMESH KUMAR KEJRIWAL 1434,VIAN AVENUE HEWLETT NEWYORK, U S A 000000 375 118672 SARITA KUKREJA 6A,STATION TERRACE, LYNFIELD,AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND TEL:6496272877 000000 1890 118605 FELIX JOAQUIM FAUSTINO FERNANDES P O BOX 11052 AL-FUTTAIM TOYOTA-NPDC RASHIDIA DUBAI 000000 750 099084 TUSHAR SHANTARAM PATKAR FINANCE & ADMINISTRATION MANAGER, C/O.HASCO & SHELL MARKETING, P.B.19440,HADDA,SANAA, REPUBLIC OF YEMEN 000000 367 118801 BHAGWAN VIROOMAL GWALANI P O BOX 5689 DUBAI U A E 000000 630 002449 SAT PAUL BHALLA A 316 NORTH OF MEDICAL ENCLAVE NEW DELHI 000000 210 118804 MUKESH SHANTILAL SHAH C/O SAHIL ENTERPRISE P O BOX 7363 MATRAH SULTANATE OF OMAN 000000 1680 071262 JATINDER LABANA C/O CAPT K S LAMANA 197 INDEPENDENT FIELD WORKSHOP C/O 56 A P O 000000 135 118573 BHOGI MOHANLAL RATHOD P O BOX 397 SHARJAH U A E 000000 367 038806 BIBHASH CHANDRA DEB D D M S HQ 1 CORPS C/O 56 A P O 000000 37 048511 ATUL CHANDRA PANDE 3974 EDMONTON COURT ANN ARBOR,ML 48103 U S A 000000 157 100436 LAXMI GRANDHI C/O MR RANGA RAO GRANDHI ASST EX ENGINEER POWER HOUSE CONSTRUCTION DIVISION CHUKHA HYDEL PROJECT 000000 270 118571 IYER KRISHNAN C/O CALEB-BRETT (UAE) PVT LTD P O BOX 97 SHARJAH U A E 000000 97 118557 BHARATKUMAR B SHUKLA 6204,N HOYNE AVENUE APARTMENT 1A CHICAGA IL 60659 U.S.A.