The Political and Administative Context of Environmental Degradation in South-India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

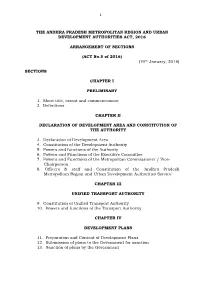

THE ANDHRA PRADESH METROPOLITAN REGION and URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITIES ACT, 2016 ARRANGEMENT of SECTIONS (ACT No.5 of 2016)

1 THE ANDHRA PRADESH METROPOLITAN REGION AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITIES ACT, 2016 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS (ACT No.5 of 2016) (19th January, 2016) SECTIONS CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title, extent and commencement 2. Definitions CHAPTER II DECLARATION OF DEVELOPMENT AREA AND CONSTITUTION OF THE AUTHORITY 3. Declaration of Development Area 4. Constitution of the Development Authority 5. Powers and functions of the Authority 6. Powers and Functions of the Executive Committee 7. Powers and Functions of the Metropolitan Commissioner / Vice- Chairperson 8. Officers & staff and Constitution of the ‘Andhra Pradesh Metropolitan Region and Urban Development Authorities Service’ CHAPTER III UNIFIED TRANSPORT AUTHORITY 9. Constitution of Unified Transport Authority 10. Powers and functions of the Transport Authority CHAPTER IV DEVELOPMENT PLANS 11. Preparation and Content of Development Plans 12. Submission of plans to the Government for sanction 13. Sanction of plans by the Government 2 14. Power to undertake preparation of area development plan or action plan or Zonal Development plan. 15. Modification to the sanctioned plans 16. Enforcement of the sanctioned plans CHAPTER V DEVELOPMENT SCHEMES (i) Types and details of Development Schemes 17. Development Schemes (4) Types of Development Schemes (5) Power of the Government to require the authority to make a development scheme 18. Provisions of the development scheme 19. Contents of the development scheme 20. Infrastructure and amenities to be provided 21. Cost of the development scheme 22. Reconstitution of plots 23. Restrictions on the use and development of land after publication of draft development scheme 24. Disputed ownership 25. Registration of document, plan or map in connection with development scheme not required. -

1 to 15 May, 2008

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIVVV (((111 tttooo 111555 MMMaaayyy,,, 222000000888))) NNNooo... 999 AGRICULTURE -(INDIA) 1 KADAMBOT SIDDIQUE Challenge and opportunity in agriculture. HINDU, 2008(2.5.2008) ** Agriculture-(India). -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COTTON 2 DESAI, Sachiketa Taking the organic route. BUSINESS INDIA, No.782, 2008(9.3.2008): P.110-111 Examines India's emergence as world's top producer of Organic cotton. ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Cotton; Organic farming -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-SUGARCANE 3 ANTONY, M.J. Bitter battles in the sugar fields. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on lack of rationalisation of sugarcane prices and coordinated policy. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Sugarcane. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-TEA 4 SATYA SUNDARAM, I Tea: Facing rough weather. FACTS FOR YOU, V.28(No.5), 2008(February): P.7-9 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Tea. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-VEGETABLES 5 RAHUL JAYARAM Brinjal battles. TELEGRAPH, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on controversies related with genetically modified brinjals. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Vegetables. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 6 GOSWAMI, Anupam Credit for a waiver. BUSINESS INDIA, No.784, 2008(6.4.2008): P.42-44 Analyses the consequences of farm loan waiver scheme announced in the current budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. 7 JOSHI, Rakesh Notes for votes. BUSINESS INDIA, No.783, 2008(23.3.2008): P.98-104 Highlights the loan waiver package offered to farmers in the present budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA) 8 Prospects of agriculture. ASSAM TRIBUNE, 2008(7.5.2008) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Policy-(India). 9 SHARMA, Manish Optimise the food-energy mix. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2008(7.5.2008) Emphasises the need for comprehensive agriculture sector reforms. -

Rural Development Contents

T'1Afr -)1.1 11\1S ( Rt \IhU 1)j Vl I(.)I '1 N 1)I I (A 11()N, \NI ) I 11-\l III - Public Disclosure Authorized kYD 5Z FILE COPYi 11171 Report No.:11171 Type: (PUB) Title: THE ASSAULT ON WORLD POVERTY : ,Author: WORLD BANK Ext.: 0 Room: Dept. OLD PUBLICATION Public Disclosure Authorized .1 If~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~1II TP0 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Return to BRDC, I 8 -203 ASSAULT on WORLD The ASSAU LT on WORLD POVE RTY Problems of Rural Development, Education and Health With a preface by Robert S. McNamara Published for THE WORLD BANK by THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS Baltimore and London Copyright © 1975 by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 75-7912 ISBN 0-8018-1745-5 (clothbound edition) ISBN 0-8018-1746-3 (paperbound edition) iv PREFACE Among our century's most urgent problems is the wholly unaccept- able poverty that blights the lives of some 2,000 million people in the more than 100 countries of the developing world. Of these 2,000 million, nearly 800 million are caught up in what can only be termed absolute poverty-a condition of life so limited as to prevent realiza- tion of the potential of the genes with which they were born; a condition of life so degrading as to be an insult to human dignity. The collection of papers in this volume, while dealing with five related subjects, share a common theme. -

7. Implementation Strategies

April 20, 2009 7. Implementation Strategies 7.1 Introduction The following Implementation Strategies address the issues and opportunities raised in Chapter 5. Action items are identified, along with responsible parties and a projected timeframe for implementation. This timeframe is expressed either as Ongoing, Short-Range (one to five years), or Long-Range (five plus years). Below is a list of responsible parties and partners in this plan. Also included in this chapter is a discussion of how to implement Activity Centers, an essential element of this Comprehensive Plan and a strategy that cuts across all of the basic components of its implementation. Parties and Partners AFT American Farmland Trust ARC Atlanta Regional Commission CPHE The Commission for the Promotion of Higher Education FHA Federal Highway Administration GC Georgia Conservancy GCF Georgia Cities Foundation GDCA Georgia Department of Community Affairs GDNR Georgia Department of Natural Resources GDOL Georgia Department of Labor GDOT Georgia Department of Transportation GEPD Georgia Environmental Protection Division GRPA Georgia Rail Passenger Authority GRTA Georgia Regional Transportation Authority HBD Hampton Building Department HCBOC Henry County Board of Commissioners HCBOE Henry County Board of Education HCBD Henry County Building Department HCC Hampton City Council HCCC Henry County Chamber of Commerce HCCE Henry County Cooperative Extension HCDA Henry County Development Authority HCDOT Henry County Department of Transportation HCDPR Henry County Development Plan -

Questions & Solutions

ENGLISH NDA-2012 EXAMINATION CAREER POINT QUESTIONS & SOLUTIONS PART – A Direction (For the next 08 items which follow) : Read the following 02 passages and answer the questions that following each passage : Passage – 1 There was a farewell ceremony on here day at school, to which my parents and I were invited. It was a touching ceremony in a solemn kind of way. The City Corporation sent a representative and so did the two main political parties. There were many speeches and my grandmother was garlanded by a girl from every class. Then the haed-girl, a particular favourite of hers, unveiled the farewell present the girls had bought for her by subscription. It was a large marble model of the Taj Mahal; it had a bulb inside and could be lit up like a table lamp. My grandmother made a speech too, but she couldn't finish it properly, for she began to cry before she got to the end of it and to stop to wipe away her tears. I turned away when she began dabbing at her eyes with a huge green handkerchief and discovered, to my surprise, that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their green hankerchief and discovered, to my surprise. that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their eyes too. I was very jealous. I remember. I had always taken it for granted that it was my own special right to love her ; I did know how to cope with the discovery that my right had been infringed by a whole school. -

Regional Rural Banks

Sources of Agricultural Loans in India Agricultural credit in India is available to farmers and other people working in the farming sector in India from various sources. Short and medium term agricultural credit requirements of farmers and others employed in the agricultural sector in India are usually met by the government, money lenders, and co-operative credit societies. Farmers with long-term loan requirements, such as a long-term agri loan or a loan for agri land purchase, can avail of loans from land development banks, the Indian government, and money lenders. The National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development (NABARD) provides long- term and short-term credit to service the needs of Indian farmers at highly competitive interest rates. The sources of agricultural finance in India can be classified into two main categories, i.e., institutional and non-institutional sources. Non-institutional sources, constitute around 40 percent of total credit availed by farmers in India. The interest rate of the non-institutional agri loans is usually very high, although the land or other assets are kept as collateral in the secured loans. include entities like relatives, landlords, traders, commission agents, and money lenders. On the other hand, institutional sources include entities such as co-operatives, NABARD, and commercial banks like the RBI and SBI Group. In the following section, the various institutional sources of agriculture business loan or agriculture loan are discussed briefly. Institutional sources The key goal of institutional credit is to enable farmers to increase their agricultural productivity and, as a consequence, their income. Institutional credit doesn’t employ exploitative practices. -

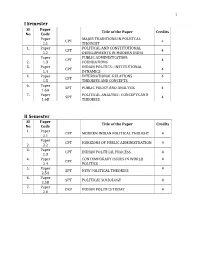

I Semester II Semester

1 I Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code Paper MAJOR TRADITIONS IN POLIITCAL CPT 4 1.1 THOUGHT 1. Paper POLITICAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.2 DEVELOPMENTS IN MODERN INDIA Paper PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION: CPT 4 2. 1.3 FOUNDATIONS 3. Paper INDIAN POLITICS : INSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.4 DYNAMICS 4. Paper INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS : 4 CPT 1.5 THEORIES AND CONCEPTS 6. Paper SPT PUBLIC POLICY AND ANALYSIS 4 1.6A 7. Paper POLITICAL ANALYSIS : CONCEPTS AND SPT 4 1.6B THEORIES II Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper CPT MODERN INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT 4 2.1 Paper CPT HORIZONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION 4 2. 2.2 3. Paper CPT INDIAN POLITICAL PROCESS 4 2.3 4. Paper CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN WORLD 4 CPT 2.4 POLITICS 5. Paper 4 SPT NEW POLITICAL THEORIES 2.5A 6. Paper SPT POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY 4 2.5B 7. Paper OEP INDIAN POLITICS TODAY 4 2.6 III Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper DEBATES IN CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL 4 CPT 3.1 THEORY Paper CPT PUBLIC GOVERNANCE 4 2. 3.2 3. Paper DIMENSIONS OF DEVELOPMENT IN CPT 4 3.3 KARNATAKA 4. Paper 4 CPT RESEARCH METHODS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE 3.4 5. Paper 4 SPT RURAL GOVERNANCE IN INDIA 3.5A 6. Paper SPT GLOBAL CHALLENGES 4 3.5B 7. Paper OEP HUMAN RIGHTS : ISSUES AND CHALLENGES 4 3.6 IV Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper MODERN WESTERN POLITICAL CPT 4 4.1 THOUGHT Paper GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS IN CPT 4 2. -

Rapporteur's Report on Institutional Framework for Agricultural Development

Ind. in. ofAgri. Econ. Vol. 53, No. 3, July-Sept. 1998 Rapporteur's Report on Institutional Framework for Agricultural Development Rapporteur: Vasant P. Gandhi* "There is an intimate connection between the institutions and technology employed,(and) the efficiency ofa market(economy) is directly shaped by the institutionalframework." Douglass C. North (1997) Winner of Nobel Prize for Economics, 1993. INTRODUCTION It is indeed highly opportune that the Indian Society of Agricultural Economics has selected the theme of institutional framework for discussion in this Conference. Worldwide, there has been a great revival of interest in institutions and their role in economic devel- opment. The old institutionalist thinking lead by Thorstein Veblen, John R. Commons and Karl Marx, among others, apparently lost its appeal in the discipline of economics with the advent of neo-classical economics. However, the inability of the neo-classical theories and models to adequately explain the uneven growth across nations, also within nations his- torically over time, as well as the recent experiences of economic reforms in different countries including Russia, India and South-East Asia, has led to a revival of interest in the role of institutions. This has led to the emergence of new institutional economic thought (Rutherford, 1994). The school is lead by the work of economists and economic historians such as Douglass North,Robert W.Fogel, Ronald Coase and Oliver E. Williamson,amongst others. While there are many similarities between the old and the new institutionalist thinking, one of the major differences is the ability of the new institutionalists to bring institutions within the frame of accepted economic theories. -

Williams, K., 1999

4.5 PSP Cover Sheet (Attach to the front of each proposal) Proposal Title: Riparian Corridor Acquisition and Restoration Assessment _____________________ Applicant Name: Bureau of Land Management, Redding Field Office ____________________ Mailing Address: 355 Hemsted Drive Redding. CA 96002 ________________________________ Telephone: (530) 224-2100 ______________________________________________________ Fax: (530) 224-2172 ___________________________________________________________ Email: [email protected] (Kelly Williams) ___________________________________________ Amount of funding requested: $ 2,200,00 for ___2 years Indicate the Topic for which you are applying (check only one box). £ Fish Passage/Fish Screens £ Introduced Species T Habitat Restoration £ Fish Management/Hatchery £ Local Watershed Stewardship £ Environmental Education £ Water Quality Does the proposal address a specified Focused Action? x yes _______no What county or counties is the project located in? Shasta and Tehama Counties ________________ Indicate the geographic area of your proposal (check only one box): T Sacramento River Mainstem__________ £ East Side Trib: _______________________ £ Sacramento Trib: ____________________ £ Suisun Marsh and Bay £ San Joaquin River Mainstem £ North Bay/South Bay: __________________ £ San Joaquin Trib: ___________________ £ Landscape (entire Bay-Delta watershed)_____ £ Delta:_____________________________ £ Other:________________________________ Indicate the primary species which the proposal addresses (check all that apply): -

Fiftieth Annual Report

FIFTIETH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 NATIONAL COOPERATIVE AGRICULTURE & RURAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS’ FEDERATION LTD. 701, BSEL TECH PARK, A Wing, Opp. Railway Station, Vashi, Navi Mumbai - 400 703 Telephone (Office): 27814114 / 426 /226 • (M.D.): 27814224 Telegram: BHUMIVIKAS • Guest House: 022-25514518 • Fax: 91-22-27814225 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.nafcard.org 2 NATIONAL CO-OPERATIVE AGRICULTURE & RURAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS’ FEDERATION LTD., MUMBAI. ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE FEDERATION NOTICE Notice is hereby given, that the Annual General Meeting of the National Co- operative Agriculture and Rural Development Banks‟ Federation Ltd., for the year 2009-2010 will be held on Monday, August 9, 2010 at 2.15 pm at Bogmallo Beach Resort, Goa to transact the following business. 1. To confirm the proceedings of the Annual General Meeting of the Federation held on 30 September 2009 at Hotel Infiniti, Indore, Madhya Pradesh. 2. Consideration of Audited Statement of Accounts for the year 2009-2010. 3. Disposal of surplus for the year 2009-10. 4. Consideration of the Statutory Report of Auditors for the year ended 31.3.2010. 5. Consideration of Compliance Report on Auditor‟s remarks in Audit Report as on 31.3.2010. 6. Consideration of Annual Report for the year 2009-2010. 7. Appointment of Statutory Auditors for the year 2010-11 and fixing audit fees. 8. Consideration of Annual Budget for the year 2011-12. In accordance with the provisions of Multi State Cooperative Societies Act, 2002, and the Byelaws of the Federation, the General Body shall consist of one representative of each member bank of the Federation who shall be either Chairman/President or the Chief Executive or a member of the Board of the member bank nominated by the Board of Directors of the respective Bank by a resolution, or the Administrator, by whatever name called, of a member bank where there is no Board. -

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics LESSON PLAN FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR: 2015-16 Programme: Arts Course/Paper Name: Principles of Macro Economics Semester: II semester Class: B.A Sl. Unit Unit to be covered as Date Unit related events / No prescribed by the components for effective university From To curriculum delivery 01. I An Overview of 11/01/2016 10/02/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Macroeconomics : Assignment, Seminar by Macroeconomics: Meaning, Students, Group Types and Scope - discussion. Importance and Limitations - Basic Concepts of Macroeconomics, Stocks, Flow and Equilibrium - National Income: Meaning and Importance - Concepts - GDP, GNP, NDP, NNP, NI, PI, DPI and Per capita Income - Circular Flow of Income 02. II Classical Theory of 11/02/2016 02/03/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Employment: Basic Assignment, Seminar by Assumptions of Classical Students, Group Theory - Classical Theory discussion. of Employment - Say’s Law of Market - Wage - Price Flexibility (Pigou’s Version) - Saving and Investment Equality - Evaluation of the Classical Theory of Employment 03. III Keynesian Theory: 03/03/2016 01/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Concepts of Effective Assignment, Seminar by Demand and its Students, Group Determinants. Equilibrium discussion. Level of Income and Employment. Consumption Function: Psychological Law of Consumption, Factors Affecting Consumption Function. Investment Function: Factors Affecting Investment Function. Multipiler - Evaluation of the Keynesian Theory of Employment. 04. IV Inflation, Deflation and 02/04/2016 29/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Business Cycle: Inflation: Assignment, Seminar by Meaning and Types - Students, Group Causes and Effects of discussion.