Growing Greener Cities in Latin America and the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Degradation and Race in Anacristina Rossi's Limón Reggae

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Degradation and Race in Anacristina Rossi's Limón reggae Joseph Timothy Morgan Jr. Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Latin American Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Morgan, Joseph Timothy Jr., "Degradation and Race in Anacristina Rossi's Limón reggae" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 151. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/151 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Degradation and Race in Anacristina Rossi’s Limón reggae Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Languages and Literatures Of Bard College By Joseph Morgan Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May, 2017 Morgan 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Melanie Nicholson, my friends, and my family. Morgan 2 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Translation……………………………………………………………………………………….26 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………...82 Morgan 3 Introduction In reality, my Senior Project began with an impromptu one-month trip to Costa Rica in 2015, the summer after the completion of my sophomore year. -

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No. 2646 Wednesday, March 20, 2013, 1:30 p.m. City Council Chamber One Technology Center – 175 E. 2nd Street, 2nd Floor Members Present Members Absent Staff Present Others Present Covey Stirling Bates Tohlen, COT Carnes Walker Fernandez VanValkenburgh, Legal Dix Huntsinger Warrick, COT Edwards Miller Leighty White Liotta Wilkerson Midget Perkins Shivel The notice and agenda of said meeting were posted in the Reception Area of the INCOG offices on Monday, March 18, 2013 at 2:10 p.m., posted in the Office of the City Clerk, as well as in the Office of the County Clerk. After declaring a quorum present, 1st Vice Chair Perkins called the meeting to order at 1:30 p.m. REPORTS: Director’s Report: Ms. Miller reported on the TMAPC Receipts for the month of February 2013. Ms. Miller submitted and explained the timeline for the general work program for 6th Street Infill Plan Amendments and Form-Based Code Revisions. Ms. Miller reported that the TMAPC website has been improved and should be online by next week. Mr. Miller further reported that there will be a work session on April 3, 2013 for the Eugene Field Small Area Plan immediately following the regular TMAPC meeting. * * * * * * * * * * * * 03:20:13:2646(1) CONSENT AGENDA All matters under "Consent" are considered by the Planning Commission to be routine and will be enacted by one motion. Any Planning Commission member may, however, remove an item by request. 1. LS-20582 (Lot-Split) (CD 3) – Location: Northwest corner of East Apache Street and North Florence Avenue (Continued from 3/6/2013) 1. -

Final Assessment Report

FINAL ASSESSMENT REPORT ASSESSMENT OF DEVELOPMENT ACCOUNT PROJECT 14/15 AK April 2018 Strengthening national capacities to design and implement rights-based policies and programmes that address care of dependent populations and women’s economic autonomy in urban development and planning FINAL ASSESSMENT REPORT ASSESSMENT OF DEVELOPMENT ACCOUNT PROJECT 14/15 AK Strengthening national capacities to design and implement rights-based policies and programmes that address care of dependent populations and women’s economic autonomy in urban development and planning April 2018 This report was prepared by Eva Otero, an external consultant, who led the evaluation and worked under the overall guidance of Raul García-Buchaca, Deputy Executive Secretary for Management and Programme Analysis of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and Sandra Manuelito, Chief of the Programme Planning and Evaluation Unit. The work was directly supervised by Irene Barquero, Programme Management Officer of the same unit, who provided strategic and technical guidance, coordination, and methodological and logistical support. The evaluation team is grateful for the support provided by its project partners at ECLAC, all of whom were represented in the Evaluation Reference Group. Warm thanks go to the programme managers and technical advisors of ECLAC for their cooperation throughout the evaluation process and their assistance in the review of the report. All comments on the evaluation report by the Evaluation Reference Group and the evaluation team of the Programme Planning and Evaluation Unit were considered by the evaluator and duly addressed, where appropriate, in the final text of the report. The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission. -

Managing Metropolitan Growth: Reflections on the Twin Cities Experience

_____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE Ted Mondale and William Fulton A Case Study Prepared for: The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy © September 2003 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE BY TED MONDALE AND WILLIAM FULTON1 I. INTRODUCTION: MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH PRAGMATICALLY Many debates about whether and how to manage urban growth on a metropolitan or regional level focus on the extremes of laissez-faire capitalism and command-and-control government regulation. This paper proposes an alternative, or "third way," of managing metropolitan growth, one that seeks to steer in between the two extremes, focusing on a pragmatic approach that acknowledges both the market and government policy. Laissez-faire advocates argue that we should leave growth to the markets. If the core cities fail, it is because people don’t want to live, shop, or work there anymore. If the first ring suburbs decline, it is because their day has passed. If exurban areas begin to choke on large-lot, septic- driven subdivisions, it is because that is the lifestyle that people individually prefer. Government policy should be used to accommodate these preferences rather than seek to shape any particular regional growth pattern. Advocates on the other side call for a strong regulatory approach. Their view is that regional and state governments should use their power to engineer precisely where and how local communities should grow for the common good. Among other things, this approach calls for the creation of a strong—even heavy-handed—regional boundary that restricts urban growth to particular geographical areas. -

Land-Use, Land-Cover Changes and Biodiversity Loss - Helena Freitas

LAND USE, LAND COVER AND SOIL SCIENCES – Vol. I - Land-Use, Land-Cover Changes and Biodiversity Loss - Helena Freitas LAND-USE, LAND-COVER CHANGES AND BIODIVERSITY LOSS Helena Freitas University of Coimbra, Portugal Keywords: land use; habitat fragmentation; biodiversity loss Contents 1. Introduction 2. Primary Causes of Biodiversity Loss 2.1. Habitat Degradation and Destruction 2.2. Habitat Fragmentation 2.3. Global Climate Change 3. Strategies for Biodiversity Conservation 3.1. General 3.2. The European Biodiversity Conservation Strategy 4. Conclusions Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary During Earth's history, species extinction has probably been caused by modifications of the physical environment after impacts such as meteorites or volcanic activity. On the contrary, the actual extinction of species is mainly a result of human activities, namely any form of land use that causes the conversion of vast areas to settlement, agriculture, and forestry, resulting in habitat destruction, degradation, and fragmentation, which are among the most important causes of species decline and extinction. The loss of biodiversity is unique among the major anthropogenic changes because it is irreversible. The importance of preserving biodiversity has increased in recent times. The global recognition of the alarming loss of biodiversity and the acceptance of its value resultedUNESCO in the Convention on Biologi – calEOLSS Diversity. In addition, in Europe, the challenge is also the implementation of the European strategy for biodiversity conservation and agricultural policies, though it is increasingly recognized that the strategy is limitedSAMPLE by a lack of basic ecological CHAPTERS information and indicators available to decision makers and end users. We have reached a point where we can save biodiversity only by saving the biosphere. -

The Land Use Element Within the Comprehensive Planning Process 2

Chapter The Land Use Element within the Comprehensive Planning Process 2 Included in this chapter: The Land Use Element: Framework and Requirements Using the Land Use Element to Integrate Elements Developing Consistency Between Plan Elements Designing a Public Participation Plan Introduction The land use element is often lengthy as it serves as a centerpiece of the comprehensive The land use element is one of nine required plan and ties together many other elements. elements within Wisconsin’s comprehensive This chapter includes a discussion of the planning law. The major goal in completing statutory requirements, a section on how to this element is to create a useful tool for use the land use element to integrate other decision makers (elected officials and plan elements, and public participation plan commissioners) to guide growth and essential to the development of the plan. development in their communities, for developers as they seek planned areas to advance projects, and for residents and others to make known their desire for growth and change in the future. Chapter 2 – The Land Use Element within the Comprehensive Planning Process Land Use Element (§66.1001(2)(h)) - Statutory language A compilation of objectives, policies, goals, maps and programs to guide the future development and redevelopment of public and private property. The element shall contain a listing of the amount, type, intensity, and net density of existing uses of land in the local governmental unit, such as agricultural, residential, commercial, industrial, and other public and private uses. The element shall analyze trends in the supply, demand and price of land, opportunities for redevelopment and existing and potential land-use conflicts. -

THE ANDHRA PRADESH METROPOLITAN REGION and URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITIES ACT, 2016 ARRANGEMENT of SECTIONS (ACT No.5 of 2016)

1 THE ANDHRA PRADESH METROPOLITAN REGION AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITIES ACT, 2016 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS (ACT No.5 of 2016) (19th January, 2016) SECTIONS CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title, extent and commencement 2. Definitions CHAPTER II DECLARATION OF DEVELOPMENT AREA AND CONSTITUTION OF THE AUTHORITY 3. Declaration of Development Area 4. Constitution of the Development Authority 5. Powers and functions of the Authority 6. Powers and Functions of the Executive Committee 7. Powers and Functions of the Metropolitan Commissioner / Vice- Chairperson 8. Officers & staff and Constitution of the ‘Andhra Pradesh Metropolitan Region and Urban Development Authorities Service’ CHAPTER III UNIFIED TRANSPORT AUTHORITY 9. Constitution of Unified Transport Authority 10. Powers and functions of the Transport Authority CHAPTER IV DEVELOPMENT PLANS 11. Preparation and Content of Development Plans 12. Submission of plans to the Government for sanction 13. Sanction of plans by the Government 2 14. Power to undertake preparation of area development plan or action plan or Zonal Development plan. 15. Modification to the sanctioned plans 16. Enforcement of the sanctioned plans CHAPTER V DEVELOPMENT SCHEMES (i) Types and details of Development Schemes 17. Development Schemes (4) Types of Development Schemes (5) Power of the Government to require the authority to make a development scheme 18. Provisions of the development scheme 19. Contents of the development scheme 20. Infrastructure and amenities to be provided 21. Cost of the development scheme 22. Reconstitution of plots 23. Restrictions on the use and development of land after publication of draft development scheme 24. Disputed ownership 25. Registration of document, plan or map in connection with development scheme not required. -

Land-Use Planning Methodology and Middle-Ground Planning Theories

Article Land-Use Planning Methodology and Middle-Ground Planning Theories Alexandros Ph. Lagopoulos 1,2 1 Department of Urban and Regional Planning and Development, School of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected]; Tel.: (+30)-2310-995-484 2 Academy of Athens, Panepistimiou 28, 10679 Athens, Greece Received: 27 August 2018; Accepted: 17 September 2018; Published: 19 September 2018 Abstract: This paper argues that a monolithic land-use planning “grand narrative” is not sufficiently flexible, but that the fragmentation into innumerable “small narratives” goes against any sense of the existence of an established domain of knowledge. Its aim is to explore the epistemological possibility for “middle ground” theories. The methodology adopted for this purpose is to take as a standard reference the methodological components of comprehensive/procedural planning and to measure against them the methodologies proposed by a corpus of other major land-use planning approaches. The outcome of this comparison is that for more than half a century, planning theories in the field of urban and regional planning have been revolving incessantly around the methodological components of the comprehensive model, which seem, at least at the present stage of our knowledge, to be the universal nucleus of the land-use planning enterprise. This paper indicates on this basis the prerequisites for the construction of middle-ground land-use planning theories and how we can pass from the formal contextual variants to real life contexts through the original articulation of planning theory with input from the findings of the actual planning systems. -

Urbanistica N. 146 April-June 2011

Urbanistica n. 146 April-June 2011 Distribution by www.planum.net Index and english translation of the articles Paolo Avarello The plan is dead, long live the plan edited by Gianfranco Gorelli Urban regeneration: fundamental strategy of the new structural Plan of Prato Paolo Maria Vannucchi The ‘factory town’: a problematic reality Michela Brachi, Pamela Bracciotti, Massimo Fabbri The project (pre)view Riccardo Pecorario The path from structure Plan to urban design edited by Carla Ferrari A structural plan for a ‘City of the wine’: the Ps of the Municipality of Bomporto Projects and implementation Raffaella Radoccia Co-planning Pto in the Val Pescara Mariangela Virno Temporal policies in the Abruzzo Region Stefano Stabilini, Roberto Zedda Chronographic analysis of the Urban systems. The case of Pescara edited by Simone Ombuen The geographical digital information in the planning ‘knowledge frameworks’ Simone Ombuen The european implementation of the Inspire directive and the Plan4all project Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen, Interoperability and spatial planners: a proposal for a land use Franco Vico ‘data model’ Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen What is a land use data model? Giuseppe De Marco Interoperability and metadata catalogues Stefano Magaudda Relationships among regional planning laws, ‘knowledge fra- meworks’ and Territorial information systems in Italy Gaia Caramellino Towards a national Plan. Shaping cuban planning during the fifties Profiles and practices Rosario Pavia Waterfrontstory Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Monica Bocci Brasilia, the city of the future is 50 years old. The urban design and the challenges of the Brazilian national capital Michele Talia To research of one impossible balance Antonella Radicchi On the sonic image of the city Marco Barbieri Urban grapes. -

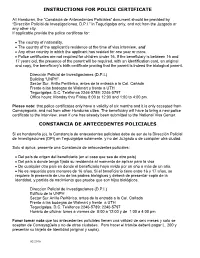

Instructions for Police Certificate

INSTRUCTIONS FOR POLICE CERTIFICATE All Honduran, the “Constacia de Antecedentes Policiales” document should be provided by “Dirección Policial de Investigaciones, D.P.I.” in Tegucigalpa only, and not from the Juzgado or any other city. If applicable provide the police certificate for: The country of nationality, The country of the applicant’s residence at the time of visa interview, and Any other country in which the applicant has resided for one year or more. Police certificates are not required for children under 16. If the beneficiary is between 16 and 17 years old, the presence of the parent will be required, with an identification card, an original and copy, the beneficiary’s birth certificate proving that the parent is indeed the biological parent. Dirección Policial de Investigaciones (D.P.I.) Building “UNPH” Sector Sur, Anillo Periférico, antes de la entrada a la Col. Cañada Frente a las bodegas de Walmart y frente a UTH Tegucigalpa, D.C. Teléfonos 2246-5789; 2246-5797 Office hours: Monday thru Friday 8:00 to 12:00 and 1:00 to 4:00 pm. Please note: that police certificates only have a validity of six months and it is only accepted from Comayaguela, and not from other Honduras cities. The beneficiary will have to bring a new police certificate to the interview, even if one has already been submitted to the National Visa Center. CONSTANCIA DE ANTECEDENTES POLICIALES Si es hondureña (o), la Constancia de antecedentes policiales debe de ser de la Dirección Policial de Investigaciones (DPI) en Tegucigalpa solamente, y no del Juzgado o de cualquier otra ciudad. -

U.S. Mission Tegucigalpa Announcement No: TGG-2018-14

VACANCY ANNOUNCEMENT U.S. Department of State U.S. Mission Tegucigalpa Announcement No: TGG-2018-14 Position Title: Public Engagement Assistant Opening Period: May 2, 2018 - May 16, 2018 Series/Grade: LE 6510 - 8, FS 6510 - 6 Salary: LE-8 L. 332,068 (annual salary) FS-6 $ 48,135 (annual salary) For More Info: Human Resources Office: Martha Nuñez Tel. 2236-9320, Ext. 4518 Mailing Address: Send to American Embassy, Human Resources Office, Room 335, and P.O. Box 3453, Tegucigalpa, Honduras. E-mail Address: Send to [email protected] Who May Apply: All Interested Applicants / All Sources For USEFM - FS is 6. Actual FS salary determined by Washington D.C. Security Clearance Required: Local Security Certification or Public Trust Duration Appointment: Indefinite subject to successful completion of probationary period. Marketing Statement: We encourage you to read and understand the Eight (8) Qualities of Overseas Employees https://careers.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Eight-Qualities-of-Overseas- Employees.pdf before you apply. Summary: The U.S. Mission in Tegucigalpa is seeking eligible and qualified applicants for the position of Public Engagement Assistant. The work schedule for this position is: • Full Time (40 hours per week) VACANCY ANNOUNCEMENT NO. TGG-2018-14 Page 2 of 5 Start date: Candidate must be able to begin working within a reasonable period of time of receipt of agency authorization and/or clearances/certifications or their candidacy may end. Supervisory Position: No Duties: The incumbent coordinates the Mission’s exchange programs for Established Opinion Leaders (EOL) audiences, including individuals and organizations such as think tanks, professional associations, civil society organizations, academic institutions.