The Case of Karnataka's Biotechnology Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 to 15 May, 2008

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIVVV (((111 tttooo 111555 MMMaaayyy,,, 222000000888))) NNNooo... 999 AGRICULTURE -(INDIA) 1 KADAMBOT SIDDIQUE Challenge and opportunity in agriculture. HINDU, 2008(2.5.2008) ** Agriculture-(India). -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COTTON 2 DESAI, Sachiketa Taking the organic route. BUSINESS INDIA, No.782, 2008(9.3.2008): P.110-111 Examines India's emergence as world's top producer of Organic cotton. ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Cotton; Organic farming -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-SUGARCANE 3 ANTONY, M.J. Bitter battles in the sugar fields. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on lack of rationalisation of sugarcane prices and coordinated policy. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Sugarcane. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-TEA 4 SATYA SUNDARAM, I Tea: Facing rough weather. FACTS FOR YOU, V.28(No.5), 2008(February): P.7-9 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Tea. -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-VEGETABLES 5 RAHUL JAYARAM Brinjal battles. TELEGRAPH, 2008(14.5.2008) Focuses on controversies related with genetically modified brinjals. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities-Vegetables. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 6 GOSWAMI, Anupam Credit for a waiver. BUSINESS INDIA, No.784, 2008(6.4.2008): P.42-44 Analyses the consequences of farm loan waiver scheme announced in the current budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. 7 JOSHI, Rakesh Notes for votes. BUSINESS INDIA, No.783, 2008(23.3.2008): P.98-104 Highlights the loan waiver package offered to farmers in the present budget. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA) 8 Prospects of agriculture. ASSAM TRIBUNE, 2008(7.5.2008) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Policy-(India). 9 SHARMA, Manish Optimise the food-energy mix. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2008(7.5.2008) Emphasises the need for comprehensive agriculture sector reforms. -

And Post-WTO Changes in Oilseed Economy of Karnataka: a Case of Groundnut

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Agricultural Economics Research Review Vol. 20 (Conference Issue) 2007 pp 529-540 Pre- and Post-WTO Changes in Oilseed Economy of Karnataka: A Case of Groundnut N.N. Karnool1, H.S. Vijayakumar2, L.B. Raghavendra3, G.M. Yogisha4, A.D. Naik5 and N.M. Kerur5 Abstract The growth in exports, economics of production and global competitiveness of groundnut has been reported over the period of 20 years (1984-85 to 2004-05) in Karnataka by collecting data from various published sources. Techniques used for the analysis are growth functions, tabular function, nominal protection coefficient and domestic resource cost. The analysis of export trends of groundnut from 1985-86 to 2004-05 has shown that quantity of groundnut export has grown annually at a compound growth rate of 9.52 per cent, whereas the value of groundnut exported has grown at a much higher rate of 13.13 per cent. Structural changes in costs are due to changes in quantity and quality of inputs associated with the technological process and also due to their prices. Groundnut has shown competitive disadvantage during the pre-WTO period, as values of NPC and DRC are more than one. But, during the post-WTO period, the competitiveness has increased as is evident from the NPC and DRC values which turned out be less than one. The study has suggested to exploit the competitiveness of Karnataka in groundnut and other oilseed crops. Introduction Oilseeds constitute one of the important groups of cash crops in Indian agriculture. -

CSM Outer Cover Front

COFFEE TO GO? TheThe vitalvital rolerole ofof IndianIndian coffeecoffee towardstowards ecosystemecosystem servicesservices andand livelihoodslivelihoods October-October- 20122012 First published in October 2012 United Nations COP-11 CBD Edition Published by Centre for Social Markets A-1 Hidden Nest, 16 Leonard Lane, Richmond Town, Bangalore 560 025, India Tel: + 91 80 40918235 Website :www.csmworld.org Centre for Social Markets. All rights reserved. COFFEE TO GO? The vital role of Indian coffee towards ecosystem services and livelihoods October 2012 United Nations COP-11 CBD Edition For more information on this report Contact Viva Kermani, Centre for Social Markets (CSM), Bangalore Email: [email protected] CONTENTS PARTNERS 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 FOREWORD 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER 2 OVERVIEW OF COFFEE CULTIVATION IN KARNATAKA 12 CHAPTER 3 STATUS OF BIODIVERSITY AND ECOSYSTEM SERVICES IN COFFEE PLANTATIONS 20 CHAPTER 4 COFFEE CULTIVATION IN KARNATAKA ANALYSIS OF EIGHT COFFEE ESTATES FROM 1999 TO 2011 44 CHAPTER 5 COFFEE CULTIVATION IN KARNATAKA IMPLICATIONS FOR LIVELIHOOD AND BIODIVERSITY 20 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 25 REFERENCES 52 A Pioneering Partnership In order to assess the extent of contribution of coffee growing practices of Southern India to ecosystem services and biodiversity, the Centre for Social Markets (CSM) and Karnataka Growers Federation (KGF) have convened a team, on behalf of the farmers and coffee plantation owners of the region, of the world’s leading practioners in the economic valuation of natural resources, entrepreneurship and coffee productivity and research. Centre for Social Markets (CSM) CSM is an independent, non-profit organization promoting entrepreneurship for the triple bottom line – people, planet and prosperity. -

Questions & Solutions

ENGLISH NDA-2012 EXAMINATION CAREER POINT QUESTIONS & SOLUTIONS PART – A Direction (For the next 08 items which follow) : Read the following 02 passages and answer the questions that following each passage : Passage – 1 There was a farewell ceremony on here day at school, to which my parents and I were invited. It was a touching ceremony in a solemn kind of way. The City Corporation sent a representative and so did the two main political parties. There were many speeches and my grandmother was garlanded by a girl from every class. Then the haed-girl, a particular favourite of hers, unveiled the farewell present the girls had bought for her by subscription. It was a large marble model of the Taj Mahal; it had a bulb inside and could be lit up like a table lamp. My grandmother made a speech too, but she couldn't finish it properly, for she began to cry before she got to the end of it and to stop to wipe away her tears. I turned away when she began dabbing at her eyes with a huge green handkerchief and discovered, to my surprise, that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their green hankerchief and discovered, to my surprise. that many of the girls sitting around me were wiping their eyes too. I was very jealous. I remember. I had always taken it for granted that it was my own special right to love her ; I did know how to cope with the discovery that my right had been infringed by a whole school. -

Executive Summary LFC Presents to You, the Economic Impact of COVID-19 from the States Will Start Easing Off Lockdown, but It Will Take Ground Zero

COVID19 Economic Impact Study Report from Ground Zero Executive Summary LFC presents to you, the economic impact of COVID-19 from The States will start easing off lockdown, but it will take Ground Zero. up to 4-5 months for India, to come out of Lock down completely In a decade of our implementation consulting experience, we have reached almost 65% of India’s tehsils. Among the top 10 states, which contribute to 75% of the To truly understand this unprecedented pandemic situation, we national GDP, 5 states, which are contributing to 31% of decided to go back and touch base with all stakeholders in the the economy, shall come out of lockdown within next 2-3 past decade and take feedback on the local conditions: months infections, the effectiveness of containment efforts, reach of government interventions and actual scenario on the ground. However other 5 states including Maharashtra, which contribute to 44% of the GDP, will be able to come out of We connected with hundreds of stakeholders: CEOs, small lockdown in 4-5 months time business owners, farmers, large distributors, retailers, truck owners and salaried employees. Based on expected post lockdown demand and All those efforts will be meaningful if it helps you in forming a effectiveness of Govt intervention - sectors contributing to clear view of the economic situation, once you finish reading the 36% of the GDP might see a quick and early revival and report. sectors contributing to 64% of GDP might experience a slow revival Thank you for your time. Ankur Kumar Indian towns will be fully back to normal by end Editor – COVID-19 Economic Impact Study Q3-FY21 Operating Partner, LFC Consulting Practice LLP Indian economy will be fully back to normal by Q2-FY22 Disclaimer: If vaccines not invented Executive Summary: States Rate of infections; Effectiveness of lockdown; Pace of testing; Rigor of containment zones management are keys to faster opening up States at a Glance Based on virus Spread, confirmed cases per million MH - Rate of testing could be significantly higher. -

I Semester II Semester

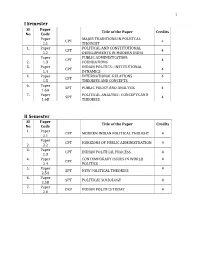

1 I Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code Paper MAJOR TRADITIONS IN POLIITCAL CPT 4 1.1 THOUGHT 1. Paper POLITICAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.2 DEVELOPMENTS IN MODERN INDIA Paper PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION: CPT 4 2. 1.3 FOUNDATIONS 3. Paper INDIAN POLITICS : INSTITUTIONAL CPT 4 1.4 DYNAMICS 4. Paper INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS : 4 CPT 1.5 THEORIES AND CONCEPTS 6. Paper SPT PUBLIC POLICY AND ANALYSIS 4 1.6A 7. Paper POLITICAL ANALYSIS : CONCEPTS AND SPT 4 1.6B THEORIES II Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper CPT MODERN INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT 4 2.1 Paper CPT HORIZONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION 4 2. 2.2 3. Paper CPT INDIAN POLITICAL PROCESS 4 2.3 4. Paper CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN WORLD 4 CPT 2.4 POLITICS 5. Paper 4 SPT NEW POLITICAL THEORIES 2.5A 6. Paper SPT POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY 4 2.5B 7. Paper OEP INDIAN POLITICS TODAY 4 2.6 III Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper DEBATES IN CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL 4 CPT 3.1 THEORY Paper CPT PUBLIC GOVERNANCE 4 2. 3.2 3. Paper DIMENSIONS OF DEVELOPMENT IN CPT 4 3.3 KARNATAKA 4. Paper 4 CPT RESEARCH METHODS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE 3.4 5. Paper 4 SPT RURAL GOVERNANCE IN INDIA 3.5A 6. Paper SPT GLOBAL CHALLENGES 4 3.5B 7. Paper OEP HUMAN RIGHTS : ISSUES AND CHALLENGES 4 3.6 IV Semester Sl Paper Title of the Paper Credits No Code 1. Paper MODERN WESTERN POLITICAL CPT 4 4.1 THOUGHT Paper GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS IN CPT 4 2. -

Dr. Yuvaraja U Dr. B Jayarama Bhat

IF : 3.62 | IC Value 80.26 VolumeVolum-5,e Issue : 3 | Iss-12,ue December: 11 | Novemb - 2016er 2014 • ISSN • ISSN No N 2277o 2277 - -8160 8179 Original Research Paper Economics Regional Disparities of Rural Road Connectivity in Karnataka: An Analysis Assistant Professor, Department of Studies Economics (PG) SDM Dr. Yuvaraja U Collage (Autonomous), Ujire-574 240, Belthangadi Tq. Dakshina Kannada Dt. Karnataka, India Dr. B Jayarama Professor of Economics, Department of Studies in Economics, Jnanasahyadri, Shankaraghatta-577451, Shivamogga Dt. Bhat Karnataka, India ABSTRACT Considering the macro-economic variables, Karnataka economy has been considered to be one of the fast growing economies in the country. The state is in the fore front in GSDP growth, IT & BT services, literacy rate is also increasing, and accessibility of infrastructures is also promising. But, in respect of micro variables, we can observe wide spread disparities among the districts, sub districts and also between the regions in Karnataka. On the one side nature and on the other side man/government have created disparity in respect of economic, social, political and religious. Among those, economic disparity has been treated to be root for the other types of disparities in any economy Even with the longtime efforts of both governments on resolving disparities, Karnataka has facing several disparities between the regions. Here, the researcher has analysed the issues of regional disparities in rural road connectivity in Karnataka. The present study has been conducted based on secondary data. KEYWORDS : Rural Road, Connectivity, PMGSY, Regional Disparity 1.1. Introduction of rural road connectivity is considered to be one of the most Based on macro-economic variables, the economy of Karnataka has threatening disparities in the state. -

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal-571440 Department of Economics LESSON PLAN FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR: 2015-16 Programme: Arts Course/Paper Name: Principles of Macro Economics Semester: II semester Class: B.A Sl. Unit Unit to be covered as Date Unit related events / No prescribed by the components for effective university From To curriculum delivery 01. I An Overview of 11/01/2016 10/02/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Macroeconomics : Assignment, Seminar by Macroeconomics: Meaning, Students, Group Types and Scope - discussion. Importance and Limitations - Basic Concepts of Macroeconomics, Stocks, Flow and Equilibrium - National Income: Meaning and Importance - Concepts - GDP, GNP, NDP, NNP, NI, PI, DPI and Per capita Income - Circular Flow of Income 02. II Classical Theory of 11/02/2016 02/03/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Employment: Basic Assignment, Seminar by Assumptions of Classical Students, Group Theory - Classical Theory discussion. of Employment - Say’s Law of Market - Wage - Price Flexibility (Pigou’s Version) - Saving and Investment Equality - Evaluation of the Classical Theory of Employment 03. III Keynesian Theory: 03/03/2016 01/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Concepts of Effective Assignment, Seminar by Demand and its Students, Group Determinants. Equilibrium discussion. Level of Income and Employment. Consumption Function: Psychological Law of Consumption, Factors Affecting Consumption Function. Investment Function: Factors Affecting Investment Function. Multipiler - Evaluation of the Keynesian Theory of Employment. 04. IV Inflation, Deflation and 02/04/2016 29/04/2016 Unit Test, Unit wise Business Cycle: Inflation: Assignment, Seminar by Meaning and Types - Students, Group Causes and Effects of discussion. -

Change in Rural Karnataka Over the Last Generation

Draft: Not to be quoted CHANGE IN KARNATAKA OVER THE LAST GENERATION: VILLAGES AND THE WIDER CONTEXT James Manor Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex 1 I. INTRODUCTION This paper examines changes that have (and have not) occurred – at the village level in Karnataka where most or the state’s residents live, and at higher levels when they impinge upon villages – since 1972. Throughout this discussion, we often encounter an oddity. Substantial changes have occurred on many (though certainly not all) fronts, but most of them have not resulted from conscious decisions by political leaders to induce dramatic change. With a small number of exceptions, political leaders have been distinctly reluctant to attempt marked changes of any description. They have not remained inert - nearly all governments have introduced changes. But almost all have proceeded quite cautiously, concentrating almost exclusively on incremental change. Four exceptions to this tendency are worth briefly noting here at the outset -- because they were important, but also to indicate how few of them there were. a) This story begins at a point – in 1972 – when Chief Minister Devaraj Urs (with the help of Karnataka’s voters) achieved a substantial, startling change. He broke the dominance that Lingayats and Vokkaligas had exercised over state-level politics since Independence. b) In 1983, the state’s party system changed when the Congress Party lost a state election for the first time. Since then, the alternation of parties at state elections has (with one notable exception) been then norm. c) After 1985, a Janata government generously empowered and funded panchayati raj institutions. -

Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214

V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Veerashaiva Vidyavardhak Sangha‘s SHREE KHASGATESH COLLEGE OF ARTS AND COMMERCE, TALIKOTI – 586214 DIST. VIJAYAPUR KARNATAKA (Affiliated to Rani Channamma University, Belagavi) Website:www.skctalikoti.com Email:[email protected] Phone No./Fax : 08356-266310 Cell : 9740220318 Self Study Report Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council For 3rd Cycle of Accreditation January, 2016 SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Shri. Khasgata Shivayogigalu SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 Shri. Ma. Ni. Pra. Virakta Mahaswamigalu SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. V.V.Sangha’s Shree Khasgatesh College of Arts and Commerce, Talikoti-586 214 CONTENTS Sl. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Covering letter 01 2 Preface and Executive Summary : The SWOC Analysis 02-13 3 Profile of the Institution : Institutional data 14-22 4 Criteria-Wise Analytical Report Criterion – I – Curricular Aspects 23-37 Criterion – II – Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 38-75 Criterion – III – Research, Consultancy and Extension 76-101 Criterion – IV – Infrastructure and Learning Resources 102-117 Criterion – V – Student Support and Progression 118-142 Criterion – VI -- Governance, Leadership and 143-166 Management Criterion – VII - Innovations and Best Practices 167-176 5 Evaluative Report of the Departments 177-234 6 Post Accreditation Initiatives 235-236 7 Compliance Report 237 8 Declaration by the Head of the Institution 238 9 Enclosures 239-287 SSR for Third Cycle of Accreditation…. -

Regional Tourism Satellite Account– Karnataka, 2009-10

Regional Tourism Satellite Account Karnataka, 2009-10 Study Commissioned by Ministry of Tourism, Government of India December, 2015 Regional Tourism Satellite Account Karnataka, 2009-10 Study Commissioned by the Ministry of Tourism, Government of India Prepared by: National Council of Applied Economic Research Parisila Bhawan, 11 I. P. Estate, New Delhi – 110002. India © National Council of Applied Economic Research, 2014 All rights reserved. The material in this publication is copyrighted. NCAER encourages the dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the publisher below. Published by Anil Kumar Sharma Acting Secretary, NCAER National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) Parisila Bhawan, 11, Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi–110 002 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Governing Body of NCAER. Regional Tourism Satellite Account– Karnataka, 2009-10 STUDY TEAM Project Leader Poonam Munjal Senior Advisor Ramesh Kolli Core Research Team K. A. Siddiqui Amit Sharma Monisha Grover Shashi Singh National Council of Applied Economic Research i Regional Tourism Satellite Account– Karnataka, 2009-10 National Council of Applied Economic Research ii Regional Tourism Satellite Account– Karnataka, 2009-10 PREFACE This is the second in a series of reports that NCAER, the National Council of Applied Economic Research, has been doing on detailed tourism satellite accounts for the states and union territories of India. With the tremendous growth of the Indian service sector, tourism as a location-specific economic activity is important at the sub-national level. -

Suppl. Syn. E Dt. 26.11.07.Pdf

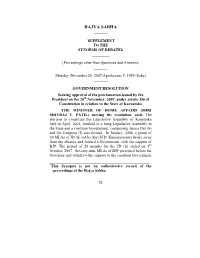

RAJYA SABHA _______ *SUPPLEMENT TO THE SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES _________ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _______ Monday, November 26, 2007/Agrahayana 5, 1929 (Saka) _______ GOVERNMENT RESOLUTION Seeking approval of the proclamation issued by the President on the 20th November, 2007, under article 356 of Constitution in relation to the State of Karnataka THE MINISTER OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI SHIVRAJ V. PATIL) moving the resolution, said: The election to constitute the Legislative Assembly of Karnataka held in April, 2004, resulted in a hung Legislative Assembly in the State and a coalition Government, comprising Janata Dal (S) and the Congress (I) was formed. In January, 2006, a group of 39 MLAs of JD (S) led by Shri H.D. Kumaraswamy broke away from the alliance and formed a Government, with the support of BJP. The period of 20 months for the JD (S) ended on 3rd October, 2007. Seventy-nine MLAs of BJP presented before the Governor and withdrew the support to the coalition Government ___________________________________________________ *This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. 92 on 6th October, 2007. Thereafter, the Chief Minister met the Governor and submitted his resignation on 8th October, 2007. The Governor, recommended invoking the President's rule in the State of Karnataka and the President's rule was proclaimed on 9th October, 2007 in the State of Karnataka under article 356 (1) of the Constitution keeping the Legislative Assembly under suspended animation. On 29th October, 2007, the JD(S)-BJP combine submitted 129 letters of individual support to the Governor -- 79 BJP, 41 JD(S), 3 JD(U) and 6 Independents -- and also signed in the register at Raj Bhawan.