The Visual Memory of Alfonso Xi and Pedro I Under the First Trastamaran Kings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mpub10110094.Pdf

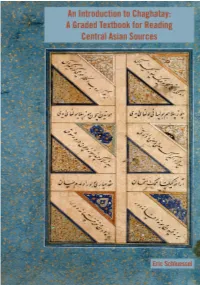

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

Andalusian Roots and Abbasid Homage in the Qubbat Al-Barudiyyin 133

andalusian roots and abbasid homage in the qubbat al-barudiyyin 133 YASSER TABBAA ANDALUSIAN ROOTS AND ABBASID HOMAGE IN THE QUBBAT AL-BARUDIYYIN IN MARRAKECH Without any question, I was attracted to the fi eld of Andalusian artisans are known to have resettled in Islamic architecture and archaeology through Oleg Morocco—it seems anachronistic in dealing with peri- Grabar’s famous article on the Dome of the Rock, ods when Andalusia itself was ruled by dynasties from which I fi rst read in 1972 in Riyadh, while contemplat- Morocco, in particular the Almoravids (1061–1147) ing what to do with the rest of my life.1 More specifi cally and the Almohads (1130–1260). More specifi cally, to the article made me think about domes as the ultimate view Almoravid architecture from an exclusively Cor- aesthetic statements of many architectural traditions doban perspective goes counter to the political and and as repositories of iconography and cosmology, cultural associations of the Almoravids, who, in addi- concepts that both Grabar and I have explored in different ways in the past few decades. This article, on a small and fragile dome in Marrakech, continues the conversation I began with Oleg long before he knew who I was. The Qubbat al-Barudiyyin in Marrakech is an enig- matic and little-studied monument that stands at the juncture of historical, cultural, and architectural trans- formations (fi g. 1). Although often illustrated, and even featured on the dust jacket of an important sur- vey of Islamic architecture,2 this monument is in fact very little known to the English-speaking scholarly world, a situation that refl ects its relatively recent dis- covery and its location in a country long infl uenced by French culture. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

MUST YOU JOIN the QUEUE? OR Lulate E Ession :Ly ~Uous A

113 N R MUST YOU JOIN THE QUEUE? OR lulaTE E essIoN :lY ~UouS A. ROSS ECKLER Morristown, New Jersey liNg ITiEs One of the most enduring pieces of orthographic folklore is the as ~ sertion that the letter Q in a word is always followed by the letter U. nT The staunchest defenders of this rule are unruffled by the counterex iNG ample Iraq, for this is a foreign proper name and not a genuine English )NE word; similarly, they quickly dismis s Qantas (an Australian airline) ~RIAL and Qiana (a synthetic fahric) as trade name s de signed to attract notice. 'Ed ~inE Actually, a considerable number of words in which Q is not followed by U can be found in English-language dictionaries. A substantial frac oring tion of these words are borrowed from Hebrew or Arabic. describing ise particular institutions or situa~ions that may have no direct counterpart Low in Western culture; if the use of these words were barred in English language texts describing the Near East, it would be necessary to re (oMenon sort to clumsy circumlocutions. Of the remainder, many come from kablE the French. >ine e To avoid being overwhelmed by examples. I somewhat arbitrarily 'ION restricted myself to uncapitalized words; furthermore, I ignored a ~d very large number of obsolete words in use in England or Scotland ,izer five hundred or more year sago, listed in the Oxford Engli sh Dictionary. ~r These words fall broadly into two classes: the substitution of W for U atloN (as in sqware for square) , and the substitution of QW for WH (as in qwere for where). -

Tunisie Tunisia

TUNISIETUNISIA ROUTEUMAYYAD DES OMEYYADES ROUTE Umayyad Route TUNISIA UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route Tunisia. Umayyad Route 1st Edition, 2016 Copyright …… Index Edition Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí Introduction Texts Mohamed Lamine Chaabani (secrétaire général de l’Association Liaisons Méditerranéennes); Mustapha Ben Soyah; Office National du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT) Umayyad Project (ENPI) 5 Photographs Office National du Tourisme Tunisien; Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí; Tunisia. History and heritage 7 Association Environnement et Patrimoine d’El Jem; Inmaculada Cortés; Carmen Pozuelo; Shutterstock Umayyad and Modern Arab Food. Graphic Design, layout and maps José Manuel Vargas Diosayuda. Diseño Editorial Gastronomy in Tunis 25 Printing XXXXXX Itinerary Free distribution ISBN Kairouan 34 978-84-96395-84-8 El Jem 50 Legal Deposit Number XXXXX-2016 Monastir 60 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, nor transmitted or recorded by any information Sousse 74 retrieval system in any form or by any means, either mechanical, photochemical, electronic, photocopying or otherwise without written permission of the editors. Zaghouan 88 © of the edition: Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí. Tunis 102 © of texts: their authors © of pictures: their authors Bibliography 138 The Umayyad Route is a project funded by the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) and led by the Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí. It gathers a network of partners in seven countries -

The Bird-Shaped Finial on Islamic Royal Parasols: a Ghaznavid Or Fatimid Innovation?

[Vicino Oriente XXIII (2019), pp. 185-206] THE BIRD-SHAPED FINIAL ON ISLAMIC ROYAL PARASOLS: A GHAZNAVID OR FATIMID INNOVATION? Valentina Laviola - University of Naples “L‟Orientale” This paper aims at investigating when and why the bird-shaped finial made its appearance on Islamic parasols through the analysis of written sources and miniature paintings. Evidence attest to the trans-regional and diachronic use of the parasol as a royal insignia whose meaning and value grew wider to symbolise the seat of government, was it the royal tent, palace or throne. Keywords: parasol; Islamic royal insignia; Iran; Ghaznavids; Fatimids 1. THE LONG-LASTING TRADITION OF THE PARASOL The parasol, a device to provide shadow repairing from the sun (or snow), is alternatively referred to as miẓalla, shamsa1 or shamsiyya in the Arabic-speaking context,2 and chatr3 in the Persian-speaking areas. It is attested as a royal insignia in almost every Islamic dynasty, but the Islamic period was not at all its starting point. In fact, the history of the parasol is far more ancient. The device has been in use throughout a very long period extending from Antiquity to the Modern Age, and in different cultural areas. Evidence come from Egypt,4 Assyria, Achaemenid and Sasanian Persia,5 where the parasol is usually held by an attendant standing behind the figure of the king as an attribute of royalty;6 a further spread concerned Asia from China7 to the west.8 Though it majorly spread in the Eastern lands, the parasol (ζκιάδειον) was known in Late Archaic and Classical Athens as well. -

Andalusia Guidebook

ANDALUSIA UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route ANDALUSIA UMAYYAD ROUTE ANDALUSIA UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route Andalusia. Umayyad Route 1st Edition 2016 Published by Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí Texts Index Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí Town Councils on the Umayyad Route in Andalusia Photographs Photographic archive of the Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí, Alcalá la Real Town Council, Algeciras Town Council, Almuñecar Town Council, Carcabuey Town Council, Cordoba City Council, Écija Town Council, Medina Sidonia Introduction Town Council, Priego de Cordoba Town Council, Zuheros Town Council, Cordoba Tourism Board, Granada Provincial Tourism Board, Seville Tourism Consortium, Ivan Zoido, José Luis Asensio Padilla, José Manuel Vera Borja, Juan Carlos González-Santiago, Xurxo Lobato, Inmaculada Cortés, Eduardo Páez, Google (Digital Globe) The ENPI Project 7 Design and layout The Umayyads in Andalusia 8 José Manuel Vargas Diosayuda. Editorial design The Umayyad Route 16 Printing ISBN: 978-84-96395-86-2 Itinerary Legal Depositit Nº. Gr-1511-2006 All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced either entirely or in part, nor may it be recorded or transmitted Algeciras 24 by a system of recovery of information, in any way or form, be it mechanical, photochemical, electronic, magnetic, Medina Sidonia 34 electro-optic by photocopying or any other means, without written permission from the publishers. Seville 44 © for the publication: Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí © for the texts: their authors Carmona 58 © for the photographs: their authors Écija 60 The Umayyad Route is a project financed by the ENPI (the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument) Cordoba 82 led by the Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí. -

Rights Guide to Winning Titles

Rights Guide to Winning Titles Literature and Children’s Books / Translation Funding Spring 2018 “The book is a pot of science and civilization, culture and knowledge, literature and the arts, and nations are not measured by material wealth only, but by their cultural authenticity.” — Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan (1971–2004) The Award The Sheikh Zayed Book Award honours the outstanding achieve- ments of innovators and thinkers in literature, the arts and human- ities in Arabic and other languag- es. Launched in 2007 and cover- Selection Process 2017–18 Timeline ing nine categories, the award promotes creativity, advances w The Award’s rigorous selection process is Arabic literature and culture, and May–October 2017 supervised by a Board of Trustees and a Nominations open provides new opportunities for Scientific Committee. Arabic-language writers. w Every year, the Scientific Committee ap- October 2017 Authors writing about Arab cul- points a group of distinguished regional Judging begins and international literary figures as judg- ture and civilisation in English, es to serve on nine selection commit- French, German, Italian and Span- February 2018 tees, one for each award category. ish also are recognised by the Longlist announced award. In addition to honouring w There are 3 to 5 judges per category, all writers and their publishers, the of whom remain anonymous to safe- March 2018 guard the independence and integrity award addresses the import- Shortlist announced of the selection process. ant role that translators play in helping bridge the cultural and w Each committee reviews all nominated April 2018 literary gap between Arab and works in a category and submits its se- Winners announced non-Arab readers and authors. -

100 Interesting Facts About Islam 11/30/14 7:10 AM

100 Interesting Facts about Islam 11/30/14 7:10 AM Histories | Facts | Archives | About Us | Contact Us | Catholicism Facts 100 Interesting Facts About . ShareShareShareShareShareShareShareMore Egypt Facts India Facts Islam Iran Facts 1. Islam is the name of the Iraq Facts religion. A person who practices Islam is known as a Muslim. Pornography Facts The adjective “Islamic” usually Scientology Facts refers to objects and places, not people. The term Serial Killers Facts “Mohammedanism” is an Spain Facts outdated term for the faith and is usually considered insulting.e 2. Islam is an Arabic word that means “peace,” “security,” and “surrender.” Muslim means “one who peacefully surrenders to God.” Anyone from any race could be Muslim; in other words, “Muslim” does not refer to a particular race.d 3. Famous Muslims in America include Janet Jackson, Muhammad Ali, Shaquille O’Neal, Mara Brock Akil (writer/producer of the series “The Game” and “Girlfriends”), Mos Def (Yasiin Bey), Mike Tyson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Ice Cube, Akon, and Anousheh Ansari, the first Muslim woman in space.h 4. Mohammad’s flight (the Hegira) from Mecca in A.D. 622 is the beginning of the rise of Islam. It also marks the beginning of the Islamic, or Hijri, calendar.c 5. Mohammad ibn Abd Allah was born around A.D. 570 in Mecca, Arabia (present-day Saudi Arabia) and died on June 8, 632, in Medina, Arabia. He claimed that when he was 40 years old, he received his first revelation from God.i 6. The Islamic Golden Age, which is traditionally dated as being the 8th–13th centuries, was marked by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate. -

The Provenance of Arabic Loan-Words in a Phonological and Semantic Study. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosoph

1 The Provenance of Arabic Loan-words Hausa:in a Phonological and Semantic study. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the UNIVERSITY OF LONDON by Mohamed Helal Ahmed Sheref El-Shazly Volume One July 1987 /" 3ISL. \ Li/NDi V ProQuest Number: 10673184 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673184 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 VOOUMEONE 3 ABSTRACT This thesis consists of an Introduction, three Chapters, and an Appendix. The corpus was obtained from the published dictionaries of Hausa together with additional material I gathered during a research visit to Northern Nigeria. A thorough examination of Hausa dictionaries yielded a large number of words of Arabic origin. The authors had not recognized all of these, and it was in no way their purpose to indicate whether the loan was direct or indirect; the dictionaries do not always give the Arabic origin, and sometimes their indications are inaccurate. The whole of my corpus amounts to some 4000 words, which are presented as an appendix. -

By Izar F. Hermes

‘IFRAJALISM’: THE [EUROPEA] OTHER I MEDIEVAL ARABIC LITERATURE AD CULTURE, 9 th -12 th CETURY (A.D.) by izar F. Hermes A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto Copyright by izar F. Hermes (2009) Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2009 Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Toronto ‘Ifranjalism’: The [European] Other in Medieval Arabic Literature and Culture, 9th -12 th Century (A.D.) by Nizar F. Hermes Many western scholars of the Middle East such as Bernard Lewis have too often claimed that medieval Arabs/Muslims did not exhibit any significant desire to discover the cultures, literatures and religions of non-Muslim peoples. Perhaps no less troubling is their assertion that only Europeans are endowed with the gift of studying foreign cultures and traveling into alien lands. In the same connection, without intending to ‘add fire’ to the already fiery polemic over Edward Said’s Orientalism , it must be said that very few of Said’s critics and defenders alike have discussed the counter, or reverse, tradition of Orientalism especially as found in the rich corpus of Classical Arabic Literature. Through introducing and exploring a cross-generic selection of non-religious Arabic prose and poetic texts such as the geo-cosmographical literature, récits de voyages , diplomatic memoirs, captivity narratives, pre-Crusade and Crusade poetry, all of which were written from the 9 th to the 12 th century(A.D.), this dissertation will present both an argument for and a demonstration of the proposition that there was no shortage of medieval Muslims who cast curious eyes and minds towards the Other and that more than a handful of them were textually and physically interested in Europe and the Euro- Christians they encountered inside and outside dār al-Islām.