Notes, Texts, and Translations I Four Songs for Voice and Violin, Opus 35

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

Connect at Calvary December 2018

Connect at Calvary December 2018 “Then an angel of the Lord stood before them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. But the angel said to them, ‘Do not be afraid; for see – I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people; to you is born this day in the city of David, a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign for you: you will find a child wrapped in bands of cloth and lying in a manger.’” Luke 2:8-12 What is the best gift that you have ever received at Christmastime? What is the best gift that you’ve given someone? I remember the year that we gave my Dad a bicycle. We had it hidden somewhere else and only a small box that was wrapped underneath the tree. He’s always able to pick up a wrapped gift and figure out what it is, so we didn’t want him to know – we wanted him to be surprised. He was very surprised when his gift was not what he though it was. We had wrapped a pair of socks in the small box. Of course, he figured it out and said thank you. But then, there was the look on his face when we brought the bicycle into the room! I’ll never forget it. My prayer for you is that you will enjoy your time of gift giving and receiving this Christmas season as you celebrate the greatest gift of all – the gift of Jesus. -

Marvin Gaye As Vocal Composer 63 Andrew Flory

Sounding Out Pop Analytical Essays in Popular Music Edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2010 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2013 2012 2011 2010 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sounding out pop : analytical essays in popular music / edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach. p. cm. — (Tracking pop) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-472-11505-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-03400-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—History and criticism. 2. Popular music— Analysis, appreciation. I. Spicer, Mark Stuart. II. Covach, John Rudolph. ML3470.S635 2010 781.64—dc22 2009050341 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the “Dramatic AABA” Form 1 john covach 2 “Only the Lonely” Roy Orbison’s Sweet West Texas Style 18 albin zak 3 Ego and Alter Ego Artistic Interaction between Bob Dylan and Roger McGuinn 42 james grier 4 Marvin Gaye as Vocal Composer 63 andrew flory 5 A Study of Maximally Smooth Voice Leading in the Mid-1970s Music of Genesis 99 kevin holm-hudson 6 “Reggatta de Blanc” Analyzing -

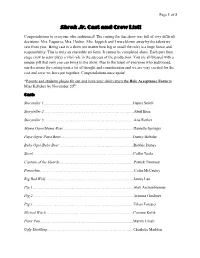

Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List!

Page 1 of 3 Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List! Congratulations to everyone who auditioned! The casting for this show was full of very difficult decisions. Mrs. Esquerra, Mrs. Hosker, Mrs. Joppich and I were blown away by the talent we saw from you. Being cast in a show (no matter how big or small the role) is a huge honor and responsibility. This is truly an ensemble art form. It cannot be completed alone. Each part from stage crew to actor plays a vital role in the success of the production. You are all blessed with a unique gift that only you can bring to the show. Due to the talent of everyone who auditioned, our decisions for casting took a lot of thought and consideration and we are very excited for the cast and crew we have put together. Congratulations once again! *Parents and students please fill out and have your child return the Role Acceptance Form to Miss Kelleher by November 20th. Cast: Storyteller 1……………………………………………………….…..Hanna Smith Storyteller 2………………………………………………………...….Abril Brea Storyteller 3……………………………..……………………..………Ana Rother Mama Ogre/Mama Bear………………………….………………...…Danielle Springer Papa Ogre/ Papa Bear……………………………………………..…Danny Boboltz Baby Ogre/Baby Bear ………………………………...…….………...Robbie Dubay Shrek…………………………………………………………….....….Collin Toole Captain of the Guards………………………………………….…...…Patrick Twomey Pinocchio……………………………………………………………....Colin McCauley Big Bad Wolf………………………………………………….….…....James Lau Pig 1……………………………………………………………….......Alex Aschenbrenner Pig 2…………………………………………………………….…......Arianna Gardiner Pig 3………………………………………………………….......……Ethan -

Here I Am, Lord Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost

Here I Am, Lord Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost by Luis Palau HERE I AM, LORD Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost Copyright © 2009 Luis Palau All rights reserved. “Here I Am, Lord” Text and music © 1981, OCP. Published by OCP. 5536 NE Hassalo, Portland, OR 97213. All rights reserved. Used by permission. In the summer of 2009, Luis Palau spoke to a small group of ministry friends in Sunriver, Oregon. This booklet is a transcription of that message. CULTIVATING A TENDER HEART FOR THE LOST Here I Am, Lord I want to read just a few verses from Matthew 18: 1-6. Keep an eye for what Jesus did here in this chapter: At that time the disciples came to Jesus and asked, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” He called a little child and had him stand among them. And he said: “I tell you the truth, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. “And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me. But if anyone causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him to have a large millstone hung around his neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.” And in another passage a bit further down (Matthew 18: 10-14) Jesus is still speaking: “See that you do not look down on one of these little ones. -

A Parent's Lullaby

A Parent’s Lullaby A Song of Hope for Bereaved Parents From Our Children Live On, by Elissa Al-Chokhachy Mom and Dad, here I am! Your child I’ll always be Loving you both with all my heart through all eternity. Will you love me even though on earth I could not stay? There were things beyond control that called me on my way. Sometimes when you miss me, I know it makes you cry. Know that I am still with you and will be by your side. If you sit quietly with me, I’ll share with you my thoughts. Ask me what you’d like to know. Then listen with your heart. Be open to the subtle ways I will say to you, “Thanks for being my Mom and Dad, for loving me through and through.” I want to make you happy. I want to make you smile. Know each time that you think of me I’m loving you all the while. I’m sorry I’ll never accomplish the things you’d hoped for me. God and I had other plans. Search and you will see ... I came to earth to be your child, to be a teacher true. There’s so much I’ve been teaching since I’ve come to be with you. You’ve learned to live in the moment and cherish each day we have. It’s the little things that mean the most, like a smile or touch of the hand. You know it doesn’t matter the things that will never be. -

When She Was Bad Script

When She Was Bad July 8, 1997 (Pink) Written by: Joss Whedon Teaser ANGLE: A HEADSTONE It's night. We hold on the stone a moment, then the camera tracks to the side, passing other stones in the EXT. GRAVEYARD/STREET - NIGHT CAMERA comes to a stone wall at the edge of the cemetery, passes over that to see the street. Two figures in the near distance. XANDER and WILLOW are walking home, eating ice cream cones. WILLOW Okay, hold on... XANDER It's your turn. WILLOW Okay, Um... "In the few hours that we had together, we loved a lifetimes worth." XANDER Terminator. WILLOW Good. Right. XANDER Okay. Let's see... (Charlton Heston) 'It's a madhouse! A m-- WILLOW Planet of the Apes. XANDER Can I finish, please? WILLOW Sorry. Go ahead. XANDER 'Madhouse!' She waits a beat to make sure he's done, then WILLOW Planet of the Apes. Good. Me now. Um... Buffy Angel Show XANDER Well? WILLOW I'm thinking. Okay. 'Use the force, Luke.' He looks at her. XANDER Do I really have to dignify that with a guess? WILLOW I didn't think of anything. It's a dumb game anyway. XANDER You got something better to do? We played rock-paper-scissors long enough, okay? My hand cramped up. WILLOW Well, sure, if you're ALWAYS scissors, of course your tendons are gonna stretch -- XANDER (interrupting) You know, I gotta say, this has really been the most boring summer ever. WILLOW Yeah, but on the plus side, no monsters or stuff. She sits on the stone wall. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

RHIANNA WYNTER Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 1Y7 +1 778 997 9040 [email protected] EDUCATION: Bachelor Degree in Creative

RHIANNA WYNTER Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 1Y7 +1 778 997 9040 [email protected] EDUCATION: Bachelor Degree in Creative Technology, JMC Academy, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2009 Graduated with High Distinction average, recipient of Elizabeth Cass award for Outstanding Academic Achievement Commercial Animation Diploma, Capilano University, BC, Canada 2014 Graduated with A+ average, recipient of Wacom Leadership Award and recipient of Governor General’s Collegiate Bronze Medal for highest GPA in University Diploma-level Course. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: August 2017- present: Bardel Entertainment, Vancouver, Canada Unit director (Storyboards) on unannounced series for Dreamworks TV Animation April 2017 – July 2017: Bardel Entertainment, Vancouver, Canada Senior Storyboard Artist on unannounced series for Dreamworks TV Animation January 2017 – April 2017: Capilano University, Vancouver, Canada Lab supervisor for 2D Animation program February 2015 – March 2017: Bardel Entertainment, Vancouver, Canada Storyboard Artist on Season 2 and 3 of “Puss in Boots” for Dreamworks TV Animation June 2015 - September 2015: Colourist and painter for children's book ‘How it Happened in Hotterly Hollow’, by Tracey Lynn Coutts April 2014 - February 2015 Bardel Entertainment, Vancouver, Canada Storyboard Trainee on Season 1 of ‘Puss in Boots’ for Dreamworks TV Animation June 2013 - present (freelance) Animated BioMedical Productions, Parramatta, Australia Graphics artist and After Effects animator on multiple projects for educational material April 2012 - August -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out -

D:\My Documents\Desktop\Website\Pages

February 2008 Bar Examination Question 1 Mom and Daddy are the divorced parents of Angel, their three year old daughter. According to Mom, she was bathing Angel after she returned home from a visitation with Daddy and Angel complained that “it hurt” around her genital area. Mom said she became concerned and questioned Angel about her complaint. She said Angel told her that she and Daddy had a “secret” that Daddy “rubbed” against her and made her hurt. Mom called the family physician, Dr. Kildare, and reported this to him. Dr. Kildare saw Angel and her mother that night at the emergency room at the local hospital. The hospital records regarding the emergency room visit contain an entry in the nurse’s notes from the now deceased Nurse Crockett indicating Angel told her “Mommy hurt me” when asked why she was at the hospital. Angel later told Dr. Kildare about the “secret” she and her Daddy had after Mom promised Angel a new doll and some ice cream. Then Dr. Kildare examined Angel and found redness and swelling in Angel’s genital area. Dr. Kildare concluded that “Angel had been sexually abused by Daddy.” He recommended that Angel be seen by a child psychologist, Dr. Feelgood. Dr. Feelgood saw Angel the following week. After interviewing, testing, and evaluating Angel he arrived at the opinion that “Angel showed no symptoms or indications of having been sexually abused.” Mom filed an action to terminate Daddy’s visitation privileges. The court, sua sponte, ordered Mom and Dad to undergo evaluations by Dr. Marcus Welby, a psychiatrist.