Cm BEAT ING 40 YEARS Focus Staff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connect at Calvary December 2018

Connect at Calvary December 2018 “Then an angel of the Lord stood before them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. But the angel said to them, ‘Do not be afraid; for see – I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people; to you is born this day in the city of David, a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign for you: you will find a child wrapped in bands of cloth and lying in a manger.’” Luke 2:8-12 What is the best gift that you have ever received at Christmastime? What is the best gift that you’ve given someone? I remember the year that we gave my Dad a bicycle. We had it hidden somewhere else and only a small box that was wrapped underneath the tree. He’s always able to pick up a wrapped gift and figure out what it is, so we didn’t want him to know – we wanted him to be surprised. He was very surprised when his gift was not what he though it was. We had wrapped a pair of socks in the small box. Of course, he figured it out and said thank you. But then, there was the look on his face when we brought the bicycle into the room! I’ll never forget it. My prayer for you is that you will enjoy your time of gift giving and receiving this Christmas season as you celebrate the greatest gift of all – the gift of Jesus. -

Here I Am, Lord Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost

Here I Am, Lord Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost by Luis Palau HERE I AM, LORD Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost Copyright © 2009 Luis Palau All rights reserved. “Here I Am, Lord” Text and music © 1981, OCP. Published by OCP. 5536 NE Hassalo, Portland, OR 97213. All rights reserved. Used by permission. In the summer of 2009, Luis Palau spoke to a small group of ministry friends in Sunriver, Oregon. This booklet is a transcription of that message. CULTIVATING A TENDER HEART FOR THE LOST Here I Am, Lord I want to read just a few verses from Matthew 18: 1-6. Keep an eye for what Jesus did here in this chapter: At that time the disciples came to Jesus and asked, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” He called a little child and had him stand among them. And he said: “I tell you the truth, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. “And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me. But if anyone causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him to have a large millstone hung around his neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.” And in another passage a bit further down (Matthew 18: 10-14) Jesus is still speaking: “See that you do not look down on one of these little ones. -

A Parent's Lullaby

A Parent’s Lullaby A Song of Hope for Bereaved Parents From Our Children Live On, by Elissa Al-Chokhachy Mom and Dad, here I am! Your child I’ll always be Loving you both with all my heart through all eternity. Will you love me even though on earth I could not stay? There were things beyond control that called me on my way. Sometimes when you miss me, I know it makes you cry. Know that I am still with you and will be by your side. If you sit quietly with me, I’ll share with you my thoughts. Ask me what you’d like to know. Then listen with your heart. Be open to the subtle ways I will say to you, “Thanks for being my Mom and Dad, for loving me through and through.” I want to make you happy. I want to make you smile. Know each time that you think of me I’m loving you all the while. I’m sorry I’ll never accomplish the things you’d hoped for me. God and I had other plans. Search and you will see ... I came to earth to be your child, to be a teacher true. There’s so much I’ve been teaching since I’ve come to be with you. You’ve learned to live in the moment and cherish each day we have. It’s the little things that mean the most, like a smile or touch of the hand. You know it doesn’t matter the things that will never be. -

When She Was Bad Script

When She Was Bad July 8, 1997 (Pink) Written by: Joss Whedon Teaser ANGLE: A HEADSTONE It's night. We hold on the stone a moment, then the camera tracks to the side, passing other stones in the EXT. GRAVEYARD/STREET - NIGHT CAMERA comes to a stone wall at the edge of the cemetery, passes over that to see the street. Two figures in the near distance. XANDER and WILLOW are walking home, eating ice cream cones. WILLOW Okay, hold on... XANDER It's your turn. WILLOW Okay, Um... "In the few hours that we had together, we loved a lifetimes worth." XANDER Terminator. WILLOW Good. Right. XANDER Okay. Let's see... (Charlton Heston) 'It's a madhouse! A m-- WILLOW Planet of the Apes. XANDER Can I finish, please? WILLOW Sorry. Go ahead. XANDER 'Madhouse!' She waits a beat to make sure he's done, then WILLOW Planet of the Apes. Good. Me now. Um... Buffy Angel Show XANDER Well? WILLOW I'm thinking. Okay. 'Use the force, Luke.' He looks at her. XANDER Do I really have to dignify that with a guess? WILLOW I didn't think of anything. It's a dumb game anyway. XANDER You got something better to do? We played rock-paper-scissors long enough, okay? My hand cramped up. WILLOW Well, sure, if you're ALWAYS scissors, of course your tendons are gonna stretch -- XANDER (interrupting) You know, I gotta say, this has really been the most boring summer ever. WILLOW Yeah, but on the plus side, no monsters or stuff. She sits on the stone wall. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

D:\My Documents\Desktop\Website\Pages

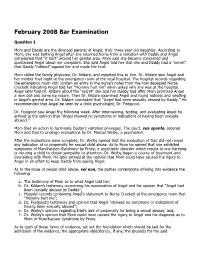

February 2008 Bar Examination Question 1 Mom and Daddy are the divorced parents of Angel, their three year old daughter. According to Mom, she was bathing Angel after she returned home from a visitation with Daddy and Angel complained that “it hurt” around her genital area. Mom said she became concerned and questioned Angel about her complaint. She said Angel told her that she and Daddy had a “secret” that Daddy “rubbed” against her and made her hurt. Mom called the family physician, Dr. Kildare, and reported this to him. Dr. Kildare saw Angel and her mother that night at the emergency room at the local hospital. The hospital records regarding the emergency room visit contain an entry in the nurse’s notes from the now deceased Nurse Crockett indicating Angel told her “Mommy hurt me” when asked why she was at the hospital. Angel later told Dr. Kildare about the “secret” she and her Daddy had after Mom promised Angel a new doll and some ice cream. Then Dr. Kildare examined Angel and found redness and swelling in Angel’s genital area. Dr. Kildare concluded that “Angel had been sexually abused by Daddy.” He recommended that Angel be seen by a child psychologist, Dr. Feelgood. Dr. Feelgood saw Angel the following week. After interviewing, testing, and evaluating Angel he arrived at the opinion that “Angel showed no symptoms or indications of having been sexually abused.” Mom filed an action to terminate Daddy’s visitation privileges. The court, sua sponte, ordered Mom and Dad to undergo evaluations by Dr. Marcus Welby, a psychiatrist. -

2019 11 Newsletter Copy

MEDICINE HAT & DISTRICT LIVE MUSIC CLUB Live Newsletter NOV 2019 Music Club Editor: Betty Bischke [email protected] In Memoriam Albert William “Billy” Jones, beloved husband of the late Nina Mabel Jones, passed away peacefully on Thursday October 24, 2019 at the age of 88 years. He leaves to cherish his memory his children Carolynn and her daughter Lindsay, and David (Tammy) and their children Alexander and Connor. He was predeceased by his wife of 53 years Nina, his parents Doris and Henry and his sister Margaret. It is difficult to capture the depth and richness of life in so brief a span. Billy’s life was dedicated to his family, friends, music and to God. Originally born and raised in Toronto, ON, Billy early on became dedicated to music. Although he also explored talents in Tool and Die Making, electronics and other passions, music and the steel guitar were the consistent theme of his professional life and for most that knew him, they were an inseparable combination. It was in Toronto that he met his wife Nina and together spent years touring the continent driven by the country and western sound that dominated his musical focus. His talent for the steel guitar was legendary. He played with some of the greats: Stompin’ Tom Connors, Hank Williams Sr., King Ganam and Tommy Hunter (to name but a few). Billy and Nina went on to pursue a family, with their children Carolynn and David, eventually moving out to Medicine Hat, AB, where they enjoyed the remainder of their lives building new relationships with great friends discovered there. -

SPECIAL BOARD of COMMISSIONERS Daniel S

SPECIAL BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS Daniel S. Bernheim, President February 26, 2020 AGENDA When addressing the Board of Commissioners, please state your name and address before making comments. As a courtesy to all, comments made from the audience during testimony or Board deliberation are not permitted and are not included as part of the public record. Public speakers are encouraged to summarize their comments and limit presentation to three minutes per item. The Board requests that the audience silence their cell phones at the beginning of the meeting. The Township has an assistive listening system to accommodate the hearing impaired. Please advise Township staff if you wish to utilize this equipment. 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call 3. Public Hearings / Adoption of Ordinances • PUBLIC HEARING AND ADOPTION OF ORDINANCE - CHAPTER 155, ZONING CODE UPDATE • PUBLIC HEARING AND ADOPTION OF ORDINANCE - CHAPTER 155, AMENDMENT OF ZONING MAP • PUBLIC HEARING AND ADOPTION OF ORDINANCE - CHAPTER 135, SUBDIVISION AND LAND DEVELOPMENT - UPDATE CROSS REFERENCES TO ZONING CODE • PUBLIC HEARING AND ADOPTION OF ORDINANCE - VARIOUS CHAPTERS - UPDATE CROSS REFERENCES TO ZONING CODE 4. Adjournment 1 AGENDA ITEM INFORMATION COMMITTEE: Building and Planning Committee ITEM: PUBLIC HEARING AND ADOPTION OF ORDINANCE - CHAPTER 155, ZONING CODE UPDATE An Ordinance to amend the Code of the Township of Lower Merion, Chapter 155, Zoning, amending that Chapter in its entirety, revoking the text as it now appears, and adopting the text attached, thereby effecting a comprehensive -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial

Radiant Beings: Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristin Michelle Ferebee Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Dr. Thomas S. Davis, Advisor Dr. Jared Gardner Dr. Brian McHale Dr. Rebekah Sheldon 1 Copyrighted by Kristin Michelle Ferebee 2019 2 Abstract The Anthropocene era— a term put forward to differentiate the timespan in which human activity has left a geological mark on the Earth, and which is most often now applied to what J.R. McNeill labels the post-1945 “Great Acceleration”— has seen a proliferation of narratives that center around questions of radioactive, toxic, and other bodily contamination and this contamination’s potential effects. Across literature, memoir, comics, television, and film, these narratives play out the cultural anxieties of a world that is itself increasingly figured as contaminated. In this dissertation, I read examples of these narratives as suggesting that behind these anxieties lies a more central anxiety concerning the sustainability of Western liberal humanism and its foundational human figure. Without celebrating contamination, I argue that the very concept of what it means to be “contaminated” must be rethought, as representations of the contaminated body shape and shaped by a nervous policing of what counts as “human.” To this end, I offer a strategy of posthuman/ist reading that draws on new materialist approaches from the Environmental Humanities, and mobilize this strategy to highlight the ways in which narratives of contamination from Marvel Comics to memoir are already rejecting the problematic ideology of the human and envisioning what might come next. -

12/2008 Mechanical, Photocopying, Recording Without Prior Written Permission of Ukchartsplus

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in Issue 383 a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, 27/12/2008 mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Number 1 Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 7” Vinyl only Download only Pre-Release For the week ending 27 December 2008 TW LW 2W Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) High Wks 1 NEW HALLELUJAH - Alexandra Burke Syco (88697446252) 1 1 1 1 2 30 43 HALLELUJAH - Jeff Buckley Columbia/Legacy (88697098847) -- -- 2 26 3 1 1 RUN - Leona Lewis Syco ( GBHMU0800023) -- -- 12 3 4 9 6 IF I WERE A BOY - Beyoncé Columbia (88697401522) 16 -- 1 7 5 NEW ONCE UPON A CHRISTMAS SONG - Geraldine Polydor (1793980) 2 2 5 1 6 18 31 BROKEN STRINGS - James Morrison featuring Nelly Furtado Polydor (1792152) 29 -- 6 7 7 2 10 USE SOMEBODY - Kings Of Leon Hand Me Down (8869741218) 24 -- 2 13 8 60 53 LISTEN - Beyoncé Columbia (88697059602) -- -- 8 17 9 5 2 GREATEST DAY - Take That Polydor (1787445) 14 13 1 4 10 4 3 WOMANIZER - Britney Spears Jive (88697409422) 13 -- 3 7 11 7 5 HUMAN - The Killers Vertigo ( 1789799) 50 -- 3 6 12 13 19 FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK - The Pogues featuring Kirsty MacColl Warner Bros (WEA400CD) 17 -- 3 42 13 3 -- LITTLE DRUMMER BOY / PEACE ON EARTH - BandAged : Sir Terry Wogan & Aled Jones Warner Bros (2564692006) 4 6 3 2 14 8 4 HOT N COLD - Katy Perry Virgin (VSCDT1980) 34 --