Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Connect at Calvary December 2018

Connect at Calvary December 2018 “Then an angel of the Lord stood before them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. But the angel said to them, ‘Do not be afraid; for see – I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people; to you is born this day in the city of David, a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign for you: you will find a child wrapped in bands of cloth and lying in a manger.’” Luke 2:8-12 What is the best gift that you have ever received at Christmastime? What is the best gift that you’ve given someone? I remember the year that we gave my Dad a bicycle. We had it hidden somewhere else and only a small box that was wrapped underneath the tree. He’s always able to pick up a wrapped gift and figure out what it is, so we didn’t want him to know – we wanted him to be surprised. He was very surprised when his gift was not what he though it was. We had wrapped a pair of socks in the small box. Of course, he figured it out and said thank you. But then, there was the look on his face when we brought the bicycle into the room! I’ll never forget it. My prayer for you is that you will enjoy your time of gift giving and receiving this Christmas season as you celebrate the greatest gift of all – the gift of Jesus. -

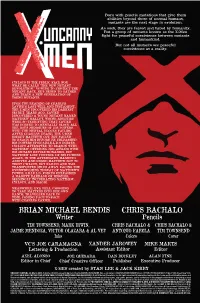

Brian Michael Bendis Chris Bachalo

Born with genetic mutations that give them abilities beyond those of normal humans, mutants are the next stage in evolution. As such, they are feared and hated by humanity. But a group of mutants known as the X-Men fight for peaceful coexistence between mutants and humankind. But not all mutants see peaceful coexistence as a reality. CYCLOPS IS THE PUBLIC FACE FOR WHAT HE CALLS “THE NEW MuTANT REVOLuTION.” VOWING TO PROTECT THE MuTANT RACE, HE’S BEGuN TO GATHER AND TRAIN A NEW GENERATION OF YOUNG MUTANTS. UPON THE READING OF CHARLES XAVIER’S LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT, THE X-MEN UNCOVERED HIS DARKEST SECRET. YEARS AGO, XAVIER DISCOVERED A YOUNG MUTANT NAMED MATTHEW MALLOY, WHOSE ABILITIES WERE SO TERRIFYING THAT XAVIER WAS FORCED TO MENTALLY BLOCK ALL THE BOY’S MEMORIES OF HIS POWERS. WITH THE MENTAL BLOCKS FAILING AFTER CHARLES’ DEATH, THE x-MEN SOUGHT MATTHEW OUT, BUT FAILED TO REACH HIM BEFORE HE UNLEASHED HIS POWERS uPON S.H.I.E.L.D.’S FORCES. CYCLOPS ATTEMPTED TO REASON WITH MATTHEW, OFFERING HIM ASYLUM WITH HIS MUTANT REVOLUTIONARIES, BUT MATTHEW LOST CONTROL OF HIS POWERS AGAIN. IN THE AFTERMATH, MAGNETO ARRIVED AND URGED MATTHEW NOT TO TRUST CYCLOPS, BUT FAILED AND WAS TRANSPORTED MILES AWAY. FACING THE OVERWHELMING THREAT OF MATTHEW’S POWER, S.H.I.E.L.D. FORCES UNLEASHED A MASSIVE BARRAGE OF MISSILES, SEEMINGLY INCINERATING MATTHEW, CYCLOPS, AND MAGIK. MEANWHILE, EVA BELL, CHOOSING TO TAKE MATTERS INTO HER OWN HANDS, TRAVELLED BACK IN TIME, COMING FACE-TO-FACE WITH CHARLES XAVIER. BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS CHRIS BACHALO Writer Pencils TIM TOWNSEND, MARK IRWIN, CHRIS BACHALO & CHRIS BACHALO & JAIME MENDOZA, VICTOR OLAZABA & AL VEY ANTONIO FABELA TIM TOWNSEND Inks Colors Cover VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA XANDER JAROWEY MIKE MARTS Lettering & Production Assistant Editor Editor AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE Editor in Chief Chief Creative Officer Publisher Executive Producer X-MEN created by STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY UNCANNY X-MEN No. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

Here I Am, Lord Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost

Here I Am, Lord Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost by Luis Palau HERE I AM, LORD Cultivating a Tender Heart for the Lost Copyright © 2009 Luis Palau All rights reserved. “Here I Am, Lord” Text and music © 1981, OCP. Published by OCP. 5536 NE Hassalo, Portland, OR 97213. All rights reserved. Used by permission. In the summer of 2009, Luis Palau spoke to a small group of ministry friends in Sunriver, Oregon. This booklet is a transcription of that message. CULTIVATING A TENDER HEART FOR THE LOST Here I Am, Lord I want to read just a few verses from Matthew 18: 1-6. Keep an eye for what Jesus did here in this chapter: At that time the disciples came to Jesus and asked, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” He called a little child and had him stand among them. And he said: “I tell you the truth, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. “And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me. But if anyone causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him to have a large millstone hung around his neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.” And in another passage a bit further down (Matthew 18: 10-14) Jesus is still speaking: “See that you do not look down on one of these little ones. -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Katalog Zur Ausstellung "60 Jahre Marvel

Liebe Kulturfreund*innen, bereits seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs befasst sich das Amerikahaus München mit US- amerikanischer Kultur. Als US-amerikanische Behörde war es zunächst für seine Bibliothek und seinen Lesesaal bekannt. Doch schon bald wurde das Programm des Amerikahauses durch Konzerte, Filmvorführungen und Vorträge ergänzt. Im Jahr 1957 zog das Amerika- haus in sein heutiges charakteristisches Gebäude ein und ist dort, nach einer vierjährigen Generalsanierung, seit letztem Jahr wieder zu finden. 2014 gründete sich die Stiftung Bay- erisches Amerikahaus, deren Träger der Freistaat Bayern ist. Heute bietet das Amerikahaus der Münchner Gesellschaft und über die Stadt- und Landesgrenzen hinaus ein vielfältiges Programm zu Themen rund um die transatlantischen Beziehungen – die Vereinigten Staaten, Kanada und Lateinamerika- und dem Schwerpunkt Demokratie an. Unsere einladenden Aus- stellungräume geben uns die Möglichkeit, Werke herausragender Künstler*innen zu zeigen. Mit dem Comicfestival München verbindet das Amerikahaus eine langjährige Partnerschaft. Wir freuen uns sehr, dass wir mit der Ausstellung „60 Jahre Marvel Comics Universe“ bereits die fünfte Ausstellung im Rahmen des Comicfestivals bei uns im Haus zeigen können. In der Vergangenheit haben wir mit unseren Ausstellungen einzelne Comickünstler, wie Tom Bunk, Robert Crumb oder Denis Kitchen gewürdigt. Vor zwei Jahren freute sich unser Publikum über die Ausstellung „80 Jahre Batman“. Dieses Jahr schließen wir mit einem weiteren Jubiläum an und feiern das 60-jährige Bestehen des Marvel-Verlags. Im Mainstream sind die Marvel- Helden durch die in den letzten Jahren immer beliebter gewordenen Blockbuster bekannt geworden, doch Spider-Man & Co. gab es schon lange davor. Das Comic-Heft „Fantastic Four #1“ gab vor 60 Jahren den Startschuss des legendären Marvel-Universums. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

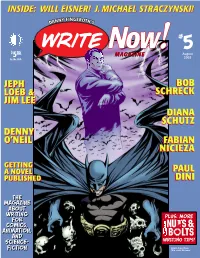

Inside: Will Eisner! J. Michael Straczynski!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: WWIILLLL EEIISSNNEERR!! JJ.. MMIICCHHAAEELL SSTTRRAACCZZYYNNSSKKII!! $ 95 MAGAAZZIINEE August 5 2003 In the USA JJEEPPHH BBOOBB LLOOEEBB && SSCCHHRREECCKK JJIIMM LLEEEE DIANA SCHUTZ DDEENNNNYY OO’’NNEEIILL FFAABBIIAANN NNIICCIIEEZZAA GGEETTTTIINNGG AA NNOOVVEELL PPAAUULL PPUUBBLLIISSHHEEDD DDIINNII Batman, Bruce Wayne TM & ©2003 DC Comics MAGAZINE Issue #5 August 2003 Read Now! Message from the Editor . page 2 The Spirit of Comics Interview with Will Eisner . page 3 He Came From Hollywood Interview with J. Michael Straczynski . page 11 Keeper of the Bat-Mythos Interview with Bob Schreck . page 20 Platinum Reflections Interview with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg . page 30 Ride a Dark Horse Interview with Diana Schutz . page 38 All He Wants To Do Is Change The World Interview with Fabian Nicieza part 2 . page 47 A Man for All Media Interview with Paul Dini part 2 . page 63 Feedback . page 76 Books On Writing Nat Gertler’s Panel Two reviewed . page 77 Conceived by Nuts & Bolts Department DANNY FINGEROTH Script to Pencils to Finished Art: BATMAN #616 Editor in Chief Pages from “Hush,” Chapter 9 by Jeph Loeb, Jim Lee & Scott Williams . page 16 Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN #167 Designer Pages from “The Blind, Part Two” by Benjamin Raab, Rich Burchett and Rodney Ramos . page 26 CHRISTOPHER DAY Script to Thumbnails to Printed Comic: Transcriber SUPERMAN ADVENTURES #40 STEVEN TICE Pages from “Old Wounds,” by Dan Slott, Ty Templeton, Michael Avon Oeming, Neil Vokes, and Terry Austin . page 36 Publisher JOHN MORROW Script to Finished Art: AMERICAN SPLENDOR Pages from “Payback” by Harvey Pekar and Dean Hapiel. page 40 COVER Script to Printed Comic 2: GRENDEL: DEVIL CHILD #1 Penciled by TOMMY CASTILLO Pages from “Full of Sound and Fury” by Diana Schutz, Tim Sale Inked by RODNEY RAMOS and Teddy Kristiansen . -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Nieuwigheden Anderstalige Strips 2014

NIEUWIGHEDEN ANDERSTALIGE STRIPS 2014 WEEK 2 Engels All New X-Men 1: Yesterday’s X-Men (€ 19,99) (Stuart Immonen & Brian Mickael Bendis / Marvel) All New X-Men / Superior Spider-Men / Indestructible Hulk: The Arms of The Octopus (€ 14,99) (Kris Anka & Mike Costa / Marvel) Avengers A.I.: Human After All (€ 16, 99) (André Araujo & Sam Humphries / Marvel) Batman: Arkham Unhinged (€ 14,99) (David Lopez & Derek Fridols / DC Comics) Batman Detective Comics 2: Scare Tactics (€ 16,99) (Tony S. Daniel / DC Comics) Batman: The Dark Knight 2: Cycle of Violence (€ 14,99) (David Finch & Gregg Hurwitz / DC Comics) Batman: The TV Stories (€ 14,99) (Diverse auteurs / DC Comics) Fantastic Four / Inhumans: Atlantis Rising (€ 39,99) (Diverse auteurs / Marvel) Simpsons Comics: Shake-Up (€ 15,99) (Studio Matt Groening / Bongo Comics) Star Wars Omnibus: Adventures (€ 24,99) (Diverse auteurs / Dark Horse) Star Wars Omnibus: Dark Times (€ 24,99) (Diverse auteurs / Dark Horse) Superior Spider-Men Team-Up: Friendly Fire (€ 17,99) (Diverse auteurs / Marvel) Swamp Thing 1 (€ 19,99) (Roger Peterson & Brian K. Vaughan / Vertigo) The Best of Wonder Wart-Hog (€ 29,95) (Gilbert Shelton / Knockabout) West Coast Avengers: Sins of the Past (€ 29,99) (Al Milgrom & Steve Englehart / Marvel) Manga – Engelstalig: Naruto 64 (€ 9,99) (Masashi Kishimoto / Viz) Naruto: Three-in-One 7 (€ 14,99) (Masashi Kishimoto / Viz) Marvel Omnibussen in aanbieding !!! Avengers: West Coast Avengers vol. 1 $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Marvel Now ! $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Punisher by Rick Remender $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! The Avengers vol. 1 $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Ultimate Spider-Man: Death of Spider-Man $ 75 NU: 39,99 Euro !!! Untold Tales of Spider-Man $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! X-Force vol.