Archaeological Desktop Assessment (Provided by Cambridge University Archaeological Unit)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Minutes

LITTLE EASTON PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE MEETING held on Wednesday 12th January 2011, 8pm in the Memorial Hall Present: Vincent Thompson (Chairman), Shirley Holden, Sue Gilbert, Bob Halford, Roger Board, Jackie Deane (Clerk) and 1 member of the public. Apologies for absence: Cllr Simon Walsh (ECC), Cllr Cecile Down (UDC) 1. Declaration of interest: None. 2. Minutes of last meeting: Were approved and signed. 3. Co-opting a Councillor: Roger Board was co-opted onto the Council and was welcomed by the Chairman. There is another vacancy to be filled and this has been advertised. V Thompson agreed to speak with an interested party with a view to another co-option before the May election. 4. Memorial Hall: It was agreed that marquee bookings for the Memorial Hall should be included in the charging policy at a percentage of the market rate. The Parish Council are happy for these to be erected on PC land and would not seek an automatic payment but would welcome a donation should an increased level of bookings be generated in the future. The toddler group had been informed about the size of shed permitted but had not yet decided on the long-term booking. 5. Street Lights: A&J lighting payment was reviewed and a decision made to settle the disputed invoice payments. 6. Vulnerable People: Correspondence was received from UDC regarding awareness and involvement. There are no vulnerable people that social services were unaware of so it was decided not to alert UDC to any changes to the emergency plan. 7. Digitial TV Switchover Sep 2011: Correspondence was received regarding outreach funding for publicity. -

Regulation 14 Consultation Draft July 2020

Stansted Mountfitchet Neighbourhood Plan Version 1.18 Regulation 14 Consultation Draft July 2020 Version 1.18 1 Stansted Mountfitchet Neighbourhood Plan Version 1.18 Stansted Mountfitchet Neighbourhood Plan Area Vision To conserve and enhance the strong historic character and rural setting of Stansted Mountfitchet by ensuring that development in the Neighbourhood Plan Area is sustainable, protects valued landscape features, strengthens a sense of community, improves the quality of life and well-being of existing and future generations. To ensure that the Parish of Stansted Mountfitchet remains “A Great Place to Live”. Comments on this Regulation 14 draft Neighbourhood Plan can be provided in the following ways: XXXXX The deadline for consultation comments to be received is XXXXX We welcome questions and suggestions or, if you require any further information, please do not hesitate to contact us: Telephone: xxxx Email: xxxx Thank you for your support. Stansted Mountfitchet Windmill 2 Stansted Mountfitchet Neighbourhood Plan Version 1.18 Contents 1. Introduction Page no. 1.1 What is Neighbourhood Planning? 6 1.2 Why does Stansted Mountfitchet need a Neighbourhood Plan? 8 1.3 The progression of the Neighbourhood Plan 9 1.4 Regulation 14 Consultation 10 1.5 How to make comments 10 1.6 Neighbourhood Plan designated area 11 2. The Parish Today 2.1 Location and context 12 2.2 Key issues for the future of the Neighbourhood Plan Area 15 2.3 Stansted Mountfitchet Neighbourhood Plan Area SWOT 20 analysis 2.4 Local planning context 21 3. The Future of the Plan Area 3.1 Vision 27 3.2 Objectives 27 4. -

Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Chigwell Parish

higwell C PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES Meeting: COUNCIL Date: 9th January 2020 Time: 8.00pm Venue: COUNCIL OFFICES, HAINAULT ROAD, CHIGWELL PRESENT: Councillors (9) Councillors; Barry Scrutton (Chairman), Naveed Akhtar, Pranav Bhanot, Jamie Braha, Kewal Chana, Alan Lion, Faiza Rizvi, Mona Sehmi and Darshan Singh Sunger. Officers (1) Anthony-Louis Belgrave – Clerk to the Council. Also in Attendance (4) # Jane Gardner – Deputy Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner for Essex. # Chief Inspector Lewis Basford – District Commander for Epping Forest & Brentwood, Essex Police. There were two members of the public in attendance. # For part of the meeting. 19.193 RECORDING OF MEETINGS NOTED that in accordance with Standing Order 3 (i) photographing, recording, broadcasting or transmitting the proceedings of a meeting may take place. 19.194 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE (2) Apologies were received from Councillors; Deborah Barlow (Vice-Chairman) and Rochelle Hodds. 19.195 OTHER ABSENCES (0) Members NOTED that there were no other absences 19.196 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES The minutes of the meetings held on 12th December 2019 were confirmed. 19.197 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST NOTED that there were no Declarations of Interest. MINUTES19/9th January 2020 - 1 - Chigwell PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES Meeting: COUNCIL Date: 9th January 2020 19.198 COMMUNICATIONS NOTED that no communications had been received: 19.199 DOCUMENTS ON DEPOSIT Members NOTED the documents that had been received and/or deposited with the Clerk to the Council during November 2019. 19.200 REPORT OF THE RESPONSIBLE FINANCIAL OFFICER a) List of Cheques After brief discussions, during which members were reminded that the largest payment was for the renovation of the cemetery driveway (Froghall Lane), it was moved by the Chairman and RESOLVED that: • the list of cheques and payments signed up to 9th January 2020 be APPROVED, and that the summary of income received and the account balance, at that date be NOTED. -

Services to Colchester 2020/21

Services to Colchester 2020/21 Routes: 505 Danbury - Maldon - Langford - Hatfield Peverel - Witham to Colchester 506 Heybridge - Gt Totham - Wickham Bishops - Tiptree - Inworth - Feering - Copford to Colchester 676 Broomfield - North Melbourne - Chelmsford - Springfield - Hatfield Peverel to Colchester 702 Frinton - Kirby Cross - Thorpe le Soken - Weeley Little Clacton Clacton on Sea St Osyth Thorrington to Colchester 716 Castle Hedingham - Sible Hedingham - Halstead - Earls Colne - Chappel - Eight Ash Green to Colchester 505 Danbury - Maldon - Langford - Hatfield Peverel - Witham to Colchester Key stops Read Read Fare Fare zones: down up zone Danbury, Eves Corner, A414 0707 1650 Danbury, Runsell Green 0709 1648 Woodham Mortimer, Oak Corner 0711 1646 Maldon, Wycke Hill, Morrisons store 0717 1641 Maldon, High St, All Saints Church 0723 1638 Langford, Holloway Road 0729 1633 Langford Church 0732 1631 B All stops are in Zone B Ulting, Does Corner 0734 1629 Hatfield Peverel, Maldon Road, New Road 0737 1626 Witham, Hatfield Rd, Jack & Jenny 0741 1622 Hatfield Road, Bridge Hospital 0742 1619 Witham High St, Newland St 0744 1617 Witham, Colchester Rd, Police station 0746 1615 THEN DIRECT TO Colchester, Norman Way Schools bus park (for County 0820 1545 High School) Colchester, Lexden Road, St School 0822 1547 Colchester, Royal Grammar School 0825 1550 506 Heybridge - Gt Totham - Wickham Bishops - Tiptree - Inworth - Feering - Copford to Colchester schools Key stops Read Read Fare Fare zones: down up zone Heybridge, Church 0723 1646 Heybridge, -

Stephensons of Essex 313 313A Saffron Walden-Great Dunmow

Stephensons of Essex 313 313A Saffron Walden-Great Dunmow Mondays to Fridays (from 4 September 2017) service no. 313 313 313A 313 notes MWF TTh Saffron Walden, High Street 0900 1100 1300 1300 Wimbish, Carver Barracks 0909 1109 - 1309 Debden, Primary School 0912 1112 - 1312 Debden, Henham Road 0916 1116 - 1316 Wimbish, Carver Barracks - - 1309 - Wimbish, Primary School - - 1315 - Howlett End, The White Hart - - 1318 - Thaxted, Post Office 0924 1124 1324 1324 Duton Hill, The Three Horseshoes 0932 1132 1332 1332 Great Easton, Great Easton Cross Roads 0935 1135 1335 1335 Little Easton, Butchers Pasture 0939 1139 1339 1339 Great Dunmow, The Broadway 0944 1144 1344 1344 Great Dunmow, High Street 0948 1148 1348 1348 Great Dunmow, Tesco 0952 1152 1352 1352 Explanation of notes: MWF this journey runs on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays only TTh this journey runs on Tuesdays and Thursdays only Stephensons of Essex 313 313A Saffron Walden-Great Dunmow Saturdays (from 4 September 2017) service no. 313 313 notes Saffron Walden, High Street 1200 1400 Wimbish, Carver Barracks 1209 1409 Debden, Primary School 1212 1412 Debden, Henham Road 1216 1416 Thaxted, Post Office 1224 1424 Duton Hill, The Three Horseshoes 1232 1432 Great Easton, Great Easton Cross Roads 1235 1435 Little Easton, Butchers Pasture 1239 1439 Great Dunmow, The Broadway 1244 1444 Great Dunmow, High Street 1248 1448 Great Dunmow, Tesco 1252 1452 Stephensons of Essex 313 313A Great Dunmow-Saffron Walden Mondays to Fridays (from 4 September 2017) service no.313A 313 313 313 notesMWF TTh Great -

Chappel & Wakes Colne At

On the cover: Wartime photo of Colchester Home Guard manning a Northover Projector © Imperial War Museum H.22527 Chappel & 1942: members of Colchester Home Wakes Colne Guard at their post with a spigot mortar © Imperial War Museum H.22530 at War 1939-1945 Follow the World War Two Trail World War Two Trail A walking trail has been compiled to take in a number of the pillboxes, anti-tank obstacles and spigot mortar pedestals – see the dotted line on the map. The area covered is south of Colchester Road encompassing The Street, Millennium Green and the main bulk of defence structures around the arches close to the river. App Download There is no fi xed route; the trail can be followed in The app is available to several directions. Parking is available either at Chappel download for free by following and Wakes Colne railway station, where there is a QR codes above. museum open from 10.00am to 4.30pm daily, or to the rear of The Swan public house. Both the railway museum Further Information Leafl ets accompanying this and and The Swan offer the opportunity for refreshments. other World War Two walks in Essex are available from Tourist Today: One of the two surviving Information Offi ces and local spigot mortar pedestals at libraries. There is a website at: Chappel Viaduct www.worldwar2heritage.com Acknowledgements World War Two trail funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, Essex Heritage Trust, the Hervey Benham Charitable Trust and the Essex and South Suffolk Community Rail Partnership. Project managed by Paul Gilman, Environment and Economy, Essex County Council. -

Colchester Halstead

Route map for Hedingham service 88 (outbound) Willowmere Camp. Park Little Cornard Great Yeldham Gestingthorpe Assington Polstead The 88 Green Toppesfield Road Poole Colne Valley Leavenheath Farm Railway Bowmans Park Wickham St Paul Stoke by Nayland Yeldham Road Castle Hedingham Lamarsh Memories Alphamstone Sible 88 Great Maplestead Hedingham Nayland Sugar Loaves Little Maplestead Bures Hamlet Bures Post Office The Lamb Pebmarsh Lane Boxted Swan Foxborough Wash Castle Farm Mound 88 Little Horkesley Wormingford Hospital High Great Horkesley Street Nether Court Colne Engaine Monklands Court Halstead Gosfield Gosfield Parker Earls Colne Horkesley Heath Lake Resort Conies Road White Colne Way The Kennels The Street Wakes Colne 88 The Lion The Fox & Colchester Road Greenstead Green Pheasant Chappel West Bergholt Highwoods New Fordstreet Road Wood Corner 88 Bike&Go Eight Ash Green Aqua Springs Bocking Churchstreet Great Tey Aldham Brick Mellor Chase Colchester And Tile Holiday Stisted Inn Lexden Stanway Head Street Hythe Copford Pattiswick Marks Tey 88 © OpenStreetMap 2.5 km 5 km 7.5 km 10 km set-05088_(1).y08 (outbound) Route map for Hedingham service 88 (inbound) Willowmere Camp. Park Little Cornard Great Yeldham Gestingthorpe Assington Polstead The 88 Green Toppesfield Road Poole Colne Valley Leavenheath Farm Railway Bowmans Park Wickham St Paul Stoke by Nayland Yeldham Road Castle Hedingham Lamarsh Memories The Bell Alphamstone 88 Sible Hedingham Sugar Little Maplestead Nayland Bures Hamlet Bures Loaves Post Office The Pebmarsh Boxted Swan -

Neighbourhood Plan (PDF)

Great Dunmow Neighbourhood Plan 2015-2032 1 | GDNP Great Dunmow Neighbourhood Plan 2015-2032 © Great Dunmow Town Council (GDTC) 2016 This Plan was produced by Great Dunmow Town Council through the office of the Town Clerk, Mrs. Caroline Fuller. It was overseen by the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group, chaired by Cllr. John Davey. Written and produced by Daniel Bacon. This document is also available on our website, www.greatdunmow-tc.gov.uk. Hard copies can be viewed by contacting GDTC or Uttlesford District Council. With thanks to the community of Great Dunmow, Planning Aid England, the Rural Community Council of Essex, Easton Planning, and Uttlesford District Council. The Steering Group consisted of: Cllr. John Davey (Chair) (GDTC & UDC), Cllr. Philip Milne (Mayor) (GDTC), Cllr. David Beedle (GDTC), Mr. William Chastell (Flitch Way Action Group), Mr. Tony Clarke, Cllr. Ron Clover (GDTC), Mr. Darren Dack (Atlantis Swimming Club), Mr. Norman Grieg (Parsonage Downs Conservation Society), Mr. Tony Harter, Cllr. Trudi Hughes (GDTC), Mr. Mike Perry (Chamber of Trade), Dr Tony Runacres, Mr. Christopher Turton (Town Team), Mr. Gary Warren (Dunmow Society). With thanks to: Rachel Hogger (Planning Aid), Benjamin Harvey (Planning Aid), Stella Scrivener (Planning Aid), Neil Blackshaw (Easton Planning), Andrew Taylor (UDC), Melanie Jones (UDC), Sarah Nicholas (UDC), Hannah Hayden (UDC), Jan Cole (RCCE), Michelle Gardner (RCCE). Maps (unless otherwise stated): Reproduced under licence from HM Stationary Office, Ordnance Survey Maps. Produced by Just Us Digital, Chelmsford Road Industrial Estate, Great Dunmow. 2 | GDNP Contents I. List of Figures 4 II. Foreword 5 III. Notes on Neighbourhood Planning 7 IV. -

Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2014

Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, Approved June 2014 Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2014 Contents 1 Part 1: Appraisal 3 Introduction 3 Planning Legislative Framework 4 Planning Policy Framework 6 The General Character and Setting of Great Easton 7 Origins and Historic Development 9 Character Analysis 11 Great Easton village 14 1 Part 2 - Management Proposals 29 Revised Conservation Area Boundary 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: The Conservation Area 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: The Potential Need to Undertake an Archaeological Field Assessment 29 Planning Control and Good Practice: Listed Buildings 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: Other Buildings that Make an Important Architectural or Historic Contribution 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: Other Distinctive Features that Make an Important Architectural or Historic Contribution 30 Planning Control and Good Practice: Important Open Spaces, Trees and Groups of Trees 30 Proposed Controls: Other Distinctive Features that make an Important Visual or Historic Contribution 30 Enhancement Proposals to Deal with Detracting Elements 31 1 Maps 32 Figure 1 - 1877 Ordnance Survey Map 32 Fig 2 - Character Analysis 33 Character Analysis Key 34 Figure 3 - Management Plan 35 Management Plan Key 36 1 Appendices 37 Appendix 1 - Sources 37 Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2014 3 Part 1: Appraisal 1 Introduction 1.1 This appraisal has been produced by Officers of Uttlesford District Council to assess the current condition of the Great Easton Conservation Area, to identify where improvements can be made and to advise of any boundary changes that are appropriate. -

Countess ROLLS-ROYCE MOTOR CARS for All Sales and Servicing Requirements of Warwick ‘No Ordinary Dealer’

The Five Parishes are proud to present the £2 Countess ROLLS-ROYCE MOTOR CARS For all sales and servicing requirements of Warwick ‘No Ordinary Dealer’ P & A Wood are authorised Rolls-Royce Motor Car dealers; we specialise in sales, service, restorations and spare parts for the entire range of Rolls-Royce and Bentley motor cars from 1904 to the present day. COUNTRY SHOWSunday 26th & Monday 27th August - 11 till 5pm Proud sponsors of the Countess of Warwick Show 2018 P & A Wood (UK) Ltd., Great Easton, Dunmow, Essex CM6 2HD, England Tel: +44 (0) 1371 852 000 • Fax: +44 (0) 1371 870 810 • www.rolls-roycemotorcars-pawood.co.uk Offi cial Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Dealer Countess of Warwick ad 2.indd 1 02/05/2018 10:44 COUNTRYSHOW To Easton Lodge Little Easton Lakes (Not included in show) Little Easton Manor Gardens Open to the public for a small charge 2 4 1 5 4 4 4 4 8 6 2 1 4 5 9 10 4 3 7 3 6 6 6 Wheelchair 7 access w.c. 2 3 7 5 1 2 4 5 8 Rectory The Barn Theatre 8 ARENA Church 4 7 4 5 2 11 1 12 3 PLOUGHING 6 4 COMPETITIONS 3 Please NOTE: Site may be subject to change and display areas are not to scale T hings to see 1 Horticultural Marquee 2 Art Show 3 Classic Car Display 4 P&A Wood Display T hings5 Animal to doMarquee COUNTRYSHOW 6 Artisan Marquee T hings7 Shire to Horses see Little Easton Lakes To Easton Lodge Little Easton (Not included in show) 2018 Guide 8 Audley End Horses Manor Gardens Open to the public Food & Drink for a small charge T hings to do T hings1 Children’s to see Area 2 Craft stalls 2 Services3 Woods 5 4 4 Bottle Stall & Raffle 1 Food5 &Dog Drink Show T hings6 Rolls to Royce do Rides 4 4 4 7 Live Entertainment 4 8 6 2 1 4 5 9 Services 10 4 3 7 3 Food & Drink T hings1 Hog to Roast see / BBQ 6 6 6 Wheelchair 2 Show Bar 7 access w.c. -

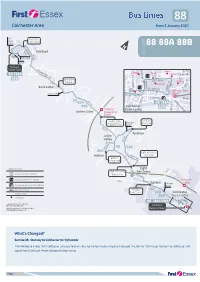

88 88A 88B C O N R Lc R H S E O U a S Halstead

Essex 88 15:58 Colchester Area from 5 January 2020 88 Halstead s 88A e High Street t 88B u © P1 nd ar ©P1ndar o 88 88A 88B C o N r lc R h s e o u a s Halstead t A d b ©P1ndar ©P1ndare ©P1ndar ©P1ndar r 1 1 2 88.88B 4 88A Halstead S N Conies Road t o o Bus Stop n r Castle e t College ©P1ndar b h rid ©P1ndar Town Museum g l ast Hill l E 88 88A e H i Hall ©P1ndar H i Fd i H l ©P1ndar l l l Art 88B e t Earls Colne H n Street S e h t r Hig Gallery The Lion a e S ©P1ndar ©P1ndar d k y l Museum n r a S ©P1ndar e o B t i Earls Colne Ea e r St John’s S u P t Q Db Colchester Town Station Church Hill A1124 ©P1ndar 6 Southway A 2 Ac 134 0 A 1 88 d M 1 B i 1 R l 88A 2 88 88A it 4 a ar e y 88B Colchester s r R 88B o Chappel & e a ©P1ndar Town Centre M d ©P1ndar Wakes Colne ©P1ndar Wakes Colne ©P1ndar Station ©P1ndar Wakes Colne Fordham Ponders Memorial Chappel Corner Road A 1 1ndar 1 ©P 24 Fordham Colne d R ll Valley i M d R w e 88 88B N 88A ©P1ndar Eight Ash Green Aldham He The Walk ath Aldham Rd Village Hall ©P1ndar ©P1ndar ©P1ndar ©P1ndar Eight Bus route 2 1 Eight Ash Green Ash Green A Db Bus stop served to Halstead Brick & Tile Bus stops served from Halstead Ea A12 Colchester Lexden Lexden Station Bus stop served to and from Halstead ©P1ndar Ac Road ©P1ndar Direction of travel Halstead 88 Road Corner 88A Colchester ©P1ndar Terminus point Town Centre ©P1ndar Timed stop 88B 88 88A 88B Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright 2019 Colchester ©P1ndar Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative Osborne Street ©P1ndar www.pindarcreative.co.uk ©P1ndar What’s Changed? Service 88: Stanway to Colchester to Highwoods The Monday to Friday 1640 Colchester to Great Yeldham journey will terminate instead at Halstead. -

CORNER HOUSE, New England, Sible Hedingham, Halstead, Essex

CORNER HOUSE, New England, Sible Hedingham, Halstead, Essex. Corner House, New England, Sible Hedingham, Halstead, the occupants to take advantage of the afternoon and evening sunshine Essex. CO9 3HY. in complete privacy. There are large expanses of neatly mown lawn, adjacent to which are a number of raised vegetable beds, ideal for those Corner House is an immaculately presented detached family home with who are keen on gardening. There are a number of attractive specimen origins believe to date back to the 17th century. The property has been trees which include flowering cherries, magnolia, and a variety of plants thoughtfully and cleverly extended by the current owners, and now and shrubs that provide year round colour and interest. provides a home of considerable character and practicality, which is well suited to modern day family life. The highest quality materials have In addition are two outbuildings, both equipped with power and light, been used throughout the property, which include solid oak doors, which have tiled roofs and weather boarded elevations that are ideal as a attractive tiled and oak floors, and a bespoke oak and glass staircase. workshop/home office, or for those with hobby interests. The property is accessed via a reception hall, with decoratively tiled To the rear of the property is a charming raised courtyard that provides flooring, and a large storage cupboard and velux roof light. The the perfect secluded BBQ area, which has log storage and a charming principal reception rooms are situated in the original building, with the former wash house that is equipped with power and light.