Department of the Environment and Heritage Submission to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OBJECT BIOGRAPHY John Smith Murdoch's Drawing Instruments

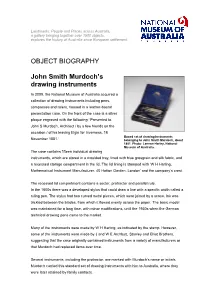

Landmarks: People and Places across Australia, a gallery bringing together over 1500 objects, explores the history of Australia since European settlement. OBJECT BIOGRAPHY John Smith Murdoch’s drawing instruments In 2009, the National Museum of Australia acquired a collection of drawing instruments including pens, compasses and rulers, housed in a leather-bound presentation case. On the front of the case is a silver plaque engraved with the following: ‘Presented to John S Murdoch, Architect / by a few friends on the occasion / of his leaving Elgin for Inverness. 18 Boxed set of drawing instruments November 1881.’ belonging to John Smith Murdoch, about 1881. Photo: Lannon Harley, National Museum of Australia. The case contains fifteen individual drawing instruments, which are stored in a moulded tray, lined with blue grosgrain and silk fabric, and a recessed storage compartment in the lid. The lid lining is stamped with ‘W H Harling, Mathematical Instrument Manufacturer, 40 Hatton Garden, London’ and the company’s crest. The recessed lid compartment contains a sector, protractor and parallel rule. In the 1600s there was a developed stylus that could draw a line with a specific width called a ruling pen. The stylus had two curved metal pieces, which were joined by a screw. Ink was trickled between the blades, from which it flowed evenly across the paper. The basic model was maintained for a long time, with minor modifications, until the 1930s when the German technical drawing pens came to the market. Many of the instruments were made by W H Harling, as indicated by the stamp. However, some of the instruments were made by J and W E Archbutt, Stanley and Elliot Brothers, suggesting that the case originally contained instruments from a variety of manufacturers or that Murdoch had replaced items over time. -

Heritage Management Plan Final Report

Australian War Memorial Heritage Management Plan Final Report Prepared by Godden Mackay Logan Heritage Consultants for the Australian War Memorial January 2011 Report Register The following report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Australian War Memorial—Heritage Management Plan, undertaken by Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd in accordance with its quality management system. Godden Mackay Logan operates under a quality management system which has been certified as complying with the Australian/New Zealand Standard for quality management systems AS/NZS ISO 9001:2008. Job No. Issue No. Notes/Description Issue Date 06-0420 1 Draft Report July 2008 06-0420 2 Second Draft Report August 2008 06-0420 3 Third Draft Report September 2008 06-0420 4 Fourth Draft Report April 2009 06-0420 5 Final Draft Report (for public comment) September 2009 06-0420 6 Final Report January 2011 Contents Page Glossary of Terms Abbreviations Conservation Terms Sources Executive Summary......................................................................................................................................i How To Use This Report .............................................................................................................................v 1.0 Introduction............................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background..........................................................................................................................................1 -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Botanical Laboratories Canberra

ArchivesACT Research Guide 1929 . ., CONI~11TTEE I WORI\S. REPORT ~ - , - ~ TOGETHER WITH " MINUTES OF EVIDEN CE RELATING TO THE PROPOSED ERECTION OF BOTANICAL LABORATORIES AT CANBERRA. I Presented pursuant to Sta.tute; ordered to be printed, lOth Septeniber, 1929. [Cost of Paper; Preparation, not given ; 835 copies; approximate cost of printing and publishing, £96. ] Printed and Published for the GovERNMENT of the CoMMONWEA LTH of AUSTRALIA by H. J. GREEN Government. Printer , Canberra . No. 57.- F.734.-PRrcE 2s. 8D. I J ArchivesACT Research Guide MEMBERS OF THE PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC WORKS. (Sixth Committee.) MALCOLM DuNCAN CAMERON, Esquire, M.P., Chairman. Senate. House of Representatives. Senator John Barnes. Percy Edmund Coleman, Esquire, M.P. Senator Herbert James Mockforcl Payne.* Josiah Francis, Esquire, M.P. Senator Matthew Reid. The Honorable Henry Gregory, M.P. Senator Burford Sampson.t r._ ' David Sydney Jackson, Esquire, M.P . David Charles McGrath, Esquire, M.P. .... • Resigned 14th August, 1929. t Appointed 14th August, 1929. INDEX. PAGE Report Ill Minutes of Evidence 1 EXTRACT FROM THE VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, No.17. Dated lith March, 1929. 6. PuBLIC WoRKS CoMMITTEE-REFERENCE oF WoRK-ERECTION OF LABORATORIES AND AN ADMINISTRATIVE BLOCK FOR THE DIVISION OF EcoNOMIC BoTANY, CANBERRA.-The Order of the Day having been read for the resumption of the debate upon the following motion of Mr. Aubrey Abbott (Minister for Home Affairs), That, in accordance with the provisions of the Commonwealth Public Works Committee Act 1913- 1921, the following proposed work be referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works for investigation and report, viz. -

SC6.13 Planning Scheme Policy – Places of Significance

SC6.13 Planning scheme policy – Places of significance SC6.13.1 Purpose of the planning scheme policy (1) The purpose of this planning scheme policy is to provide guidance on preparing a statement of significance, impact assessment report, archaeological management plan, conservation management plan and an archival report. The planning scheme policy also contains the statements of cultural significance for each of the places of local significance which must be considered when assessing development applications of the place. SC6.13.2 Information Council may request SC6.13.2.1 Guidelines for preparing a Statement of significance (1) An appropriately qualified heritage consultant is to prepare the statement of significance. (2) A statement of cultural significance is to be prepared in accordance with the ICOMOS Burra Charter, 1999 and associated guidelines and the Queensland Government publication, using the criteria – a methodology. (3) The statement of cultural significance describes the importance of a place and the values that make it important. (4) A statement of cultural significance is to include the following: (a) Place details including place name, if the place is known by any other alternative; names and details if it listed on any other heritage registers; (b) Location details including the physical address, lot and plan details, coordinates and the specific heritage boundary details; (c) Statement/s of the cultural significance with specific reference to the cultural significance criteria; (d) A description of the thematic history and context of the place demonstrating an understanding of the history, key themes and fabric of the place within the context of its class; (e) A description of the place addressing the architectural description, locational description and the integrity and condition of the place; (f) Images and plans of the place both current and historical if available; (g) Details of the author/s, including qualifications and the date of the report. -

The Former High Court Building Is Important As the First Headquarters of the High Court of Australia

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: High Court of Australia (former) Other Names: Federal Court Place ID: 105896 File No: 2/11/033/0434 Nomination Date: 13/06/2006 Principal Group: Law and Enforcement Status Legal Status: 15/06/2006 - Nominated place Admin Status: 16/06/2006 - Under assessment by AHC--Australian place Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Melbourne Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): Address: 450 Little Bourke St, Melbourne, VIC 3000 LGA: Melbourne City VIC Location/Boundaries: 450 Little Bourke Street, Melbourne, comprising the whole of Allotment 13B Section 19, City of Melbourne. Assessor's Summary of Significance: The former High Court Building is important as the first headquarters of the High Court of Australia. It operated from 1928 to 1980, a time when many Constitutional and other landmark judicial decisions were made affecting the nation’s social and political life. The whole of the building and its interior design, fitout (including original furniture) and architectural features bear witness to these events. As the first purpose built building for the home of the nation's High Court, it combines the then budgetary austerity of the Commonwealth with a skilled functional layout, where the public entry is separated from the privacy of the Justices’ chambers and the Library by the three central Courts, in a strongly modelled exterior, all viewed as a distinct design entity. The original stripped classical style and the integrity of the internal detailing and fit out of the Courts and Library is overlaid by sympathetic additions with contrasting interior Art Deco design motifs. -

INTRODUCTION John Smith Murdoch This Thesis

Introduction 1 INTRODUCTION John Smith Murdoch This thesis presents John Smith Murdoch (1862-1945), architect and public servant and examines the significance of his contribution to the development of Australian architecture between 1885 and 1929. His ability to combine successfully the often mutually exclusive roles of designer and Government employee earned him considerable national respect from the architectural profession and the public service. In this dual role, substantial design constraints were placed upon him which included the economic considerations determined by the public purse. As a representative of Government, he was also entrusted to embody the nation's values in architectural terms, as well as adhering to the architectural practices of his profession. The extent of his architectural contribution in Australia is highlighted by Murdoch himself: As Designer or Supervisor, or both, the buildings engaged upon number very many hundreds of every kind, and in value from a quarter of a million pounds downwards. Due to my position in the Department, probably no person has had a wider experience of buildings in Australia including its tropics ... [I have had] a leading connection with the design of practically all Commonwealth building works during the above period [1904-28].1 A List of Works is provided in Appendix 1 as evidence of his substantial architectural repertoire; the extent of which suggests that the work is of historical importance. Despite a prolific output and acknowledgement for raising 'architecture in Australia to a high level'2 between 1910 and 1920, this is the first critical study of his life and work. Three reasons are immediately evident in determining why Murdoch has not previously been the subject of scholarly analysis. -

Periodic Report

australian heritage council Periodic Report march 2004 – february 2007 australian heritage council Periodic Report march 2004 – february 2007 Published by the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Water Resources ISBN: 9780642553513 © Commonwealth of Australia 2007 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca Cover images: (left to right): Royal National Park, Ned Kelly’s armour, Old Parliament House, Port Arthur, Nourlangie rock art. © Department of the Environment and Water Resources (and associated photographers). Printed by Union Offset Printers Designed and typeset by Fusebox Design 2 australian heritage council – periodic report The Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister Australian Heritage Council: Periodic Report On 19 February, 2004 the Minister for the Environment and Heritage appointed the Australian Heritage Council (the Council) to act as his principal adviser on heritage matters with roles and responsibilities laid out in the Australian Heritage Council Act 2003 (the AHC Act). Under Section 24A of the AHC Act, Council may prepare a report on any matter related to its functions and provide the report to the Minister for laying before each House of the Parliament within 15 sitting days after the day on which the Minister receives the report. -

Central City (Hoddle Grid) Heritage Review 2011

Central City (Hoddle Grid) Heritage Review 2011 Collie, R & Co warehouse, 194-196 Little Lonsdale Victorian Cricket Association Building (VCA), 76-80 Street, Melbourne 3000 ........................................... 453 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000..............................285 Cavanagh's or Tucker & Co's warehouse, 198-200 Schuhkraft & Co warehouse, later YMCA, and AHA Little Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000 ................... 459 House, 130-132 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000....292 Women's Venereal Disease Clinic, 372-378 Little Cobden Buildings, later Mercantile & Mutual Chambers Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000............................ 466 and Fletcher Jones building, 360-372 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000 .......................................................298 Cleve's Bonded Store, later Heymason's Free Stores, 523-525 Little Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000 ..... 473 Waterside Hotel, 508-510 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000 .........................................................................308 Blessed Sacrament Fathers Monastery, St Francis, 326 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000............................ 479 Coffee Tavern (No. 2), 516-518 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000 .......................................................315 Michaelis Hallenstein & Co building, 439-445 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000 ........................................... 485 Savings Bank of Victoria Flinders Street branch, former, 520-522 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000....322 Watson's warehouse, later 3LO and 3AR studios, 3AW Radio Theatre, -

Religious Self-Fashioning As a Motive in Early Modern Diary Keeping: the Evidence of Lady Margaret Hoby's Diary 1599-1603, Travis Robertson

From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond Proceedings of the conference held at St Francis Theological College, Milton, February 12-14 2010 Edited by Marcus Harmes Lindsay Henderson & Gillian Colclough © Contributors 2010 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. First Published 2010 Augustine to Anglicanism Conference www.anglicans-in-australia-and-beyond.org National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Harmes, Marcus, 1981 - Colclough, Gillian. Henderson, Lindsay J. (editors) From Augustine to Anglicanism: the Anglican Church in Australia and beyond: proceedings of the conference. ISBN 978-0-646-52811-3 Subjects: 1. Anglican Church of Australia—Identity 2. Anglicans—Religious identity—Australia 3. Anglicans—Australia—History I. Title 283.94 Printed in Australia by CS Digital Print http://www.csdigitalprint.com.au/ Acknowledgements We thank all of the speakers at the Augustine to Anglicanism Conference for their contributions to this volume of essays distinguished by academic originality and scholarly vibrancy. We are particularly grateful for the support and assistance provided to us by all at St Francis’ Theological College, the Public Memory Research Centre at the University of Southern Queensland, and Sirromet Wines. Thanks are similarly due to our colleagues in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Southern Queensland: librarians Vivienne Armati and Alison Hunter provided welcome assistance with the cataloguing data for this volume, while Catherine Dewhirst, Phillip Gearing and Eleanor Kiernan gave freely of their wise counsel and practical support. -

An Interesting Point © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This Work Is Copyright

AN INTERESTING POINT © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Cover Image: ‘Flying Start’ by Norm Clifford - QinetiQ Pty Ltd National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Campbell-Wright, Steve, author. Title: An interesting point : a history of military aviation at Point Cook 1914-2014 / Steve Campbell-Wright. ISBN: 9781925062007 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aeronautics, Military--Victoria--Point Cook--History. Air pilots, Military--Victoria--Point Cook. Point Cook (Vic.)--History. Other. Authors/Contributors: Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. Dewey Number: 358.400994 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre F3-G, Department of Defence Telephone: + 61 2 6128 7041 PO Box 7932 Facsimile: + 61 2 6128 7053 CANBERRA BC 2610 Email: [email protected] AUSTRALIA Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower AN INTERESTING A History of Military Aviation at Point Cook 1914 – 2014 Steve Campbell-Wright ABOUT THE AUTHOR Steve Campbell-Wright has served in the Air Force for over 30 years. He holds a Masters degree in arts from the University of Melbourne and postgraduate qualifications in cultural heritage from Deakin University. -

Former Rockbank Beam Wireless Station

Shire of Melton Heritage Study – Volume 5 Heritage Overlay No.: 108 Citation No.: 311 Place: Former Rockbank Beam Wireless Station Other Names of Place: Former Australian Beam Wireless Receiving Station. Location: 653-701 Greigs Road East, Mt Cottrell Critical Dates: Built 1926; Opened 1927; Closed 1969. Existing Heritage Listings: None. Recommended Level of Significance: NATIONAL/STATE Statement of Significance: Rockbank Park, 653-701 Greigs Road, Rockbank, is significant as the substantially intact former residential quarters of the Australian Beam Wireless Receiving Station, which commenced operation in 1927, and possibly as a fine example of early twentieth century „Commonwealth Departmental style‟ architecture (with particular Mission Revival overtones) in a landscape setting. It may have been designed by the Commonwealth Department of Works and Railways which was under the design control of J.S. Murdoch, Commonwealth Chief Architect and Director General of Works, and was built in 1926. The buildings and landscape setting at Rockbank Park appear to be remarkably intact. Consultants: David Moloney, David Rowe, Pamela Jellie (2006) Shire of Melton Heritage Study – Volume 5 Rockbank Park at 653-701 Greigs Road is architecturally significant at a STATE level (AHC D.2, E.1). The main building and associated four Bungalows demonstrate outstanding original design qualities that appear to relate to the Commonwealth‟s „Departmental style‟ with specific Mission Revival overtones. The original design qualities of the main building include the elaborate arched portico and carriage way that appears to draw on the Mission Revival design of the San Carlos Church, Monterey, U.S.A, together with the long hipped roof form and rear hipped roofed wings clad in terra cotta tiles: the whole forming a U plan.