INTRODUCTION John Smith Murdoch This Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

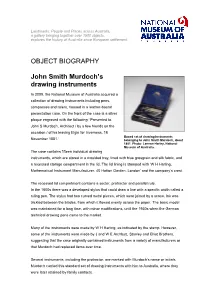

OBJECT BIOGRAPHY John Smith Murdoch's Drawing Instruments

Landmarks: People and Places across Australia, a gallery bringing together over 1500 objects, explores the history of Australia since European settlement. OBJECT BIOGRAPHY John Smith Murdoch’s drawing instruments In 2009, the National Museum of Australia acquired a collection of drawing instruments including pens, compasses and rulers, housed in a leather-bound presentation case. On the front of the case is a silver plaque engraved with the following: ‘Presented to John S Murdoch, Architect / by a few friends on the occasion / of his leaving Elgin for Inverness. 18 Boxed set of drawing instruments November 1881.’ belonging to John Smith Murdoch, about 1881. Photo: Lannon Harley, National Museum of Australia. The case contains fifteen individual drawing instruments, which are stored in a moulded tray, lined with blue grosgrain and silk fabric, and a recessed storage compartment in the lid. The lid lining is stamped with ‘W H Harling, Mathematical Instrument Manufacturer, 40 Hatton Garden, London’ and the company’s crest. The recessed lid compartment contains a sector, protractor and parallel rule. In the 1600s there was a developed stylus that could draw a line with a specific width called a ruling pen. The stylus had two curved metal pieces, which were joined by a screw. Ink was trickled between the blades, from which it flowed evenly across the paper. The basic model was maintained for a long time, with minor modifications, until the 1930s when the German technical drawing pens came to the market. Many of the instruments were made by W H Harling, as indicated by the stamp. However, some of the instruments were made by J and W E Archbutt, Stanley and Elliot Brothers, suggesting that the case originally contained instruments from a variety of manufacturers or that Murdoch had replaced items over time. -

Heritage Management Plan Final Report

Australian War Memorial Heritage Management Plan Final Report Prepared by Godden Mackay Logan Heritage Consultants for the Australian War Memorial January 2011 Report Register The following report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Australian War Memorial—Heritage Management Plan, undertaken by Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd in accordance with its quality management system. Godden Mackay Logan operates under a quality management system which has been certified as complying with the Australian/New Zealand Standard for quality management systems AS/NZS ISO 9001:2008. Job No. Issue No. Notes/Description Issue Date 06-0420 1 Draft Report July 2008 06-0420 2 Second Draft Report August 2008 06-0420 3 Third Draft Report September 2008 06-0420 4 Fourth Draft Report April 2009 06-0420 5 Final Draft Report (for public comment) September 2009 06-0420 6 Final Report January 2011 Contents Page Glossary of Terms Abbreviations Conservation Terms Sources Executive Summary......................................................................................................................................i How To Use This Report .............................................................................................................................v 1.0 Introduction............................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background..........................................................................................................................................1 -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Botanical Laboratories Canberra

ArchivesACT Research Guide 1929 . ., CONI~11TTEE I WORI\S. REPORT ~ - , - ~ TOGETHER WITH " MINUTES OF EVIDEN CE RELATING TO THE PROPOSED ERECTION OF BOTANICAL LABORATORIES AT CANBERRA. I Presented pursuant to Sta.tute; ordered to be printed, lOth Septeniber, 1929. [Cost of Paper; Preparation, not given ; 835 copies; approximate cost of printing and publishing, £96. ] Printed and Published for the GovERNMENT of the CoMMONWEA LTH of AUSTRALIA by H. J. GREEN Government. Printer , Canberra . No. 57.- F.734.-PRrcE 2s. 8D. I J ArchivesACT Research Guide MEMBERS OF THE PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC WORKS. (Sixth Committee.) MALCOLM DuNCAN CAMERON, Esquire, M.P., Chairman. Senate. House of Representatives. Senator John Barnes. Percy Edmund Coleman, Esquire, M.P. Senator Herbert James Mockforcl Payne.* Josiah Francis, Esquire, M.P. Senator Matthew Reid. The Honorable Henry Gregory, M.P. Senator Burford Sampson.t r._ ' David Sydney Jackson, Esquire, M.P . David Charles McGrath, Esquire, M.P. .... • Resigned 14th August, 1929. t Appointed 14th August, 1929. INDEX. PAGE Report Ill Minutes of Evidence 1 EXTRACT FROM THE VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, No.17. Dated lith March, 1929. 6. PuBLIC WoRKS CoMMITTEE-REFERENCE oF WoRK-ERECTION OF LABORATORIES AND AN ADMINISTRATIVE BLOCK FOR THE DIVISION OF EcoNOMIC BoTANY, CANBERRA.-The Order of the Day having been read for the resumption of the debate upon the following motion of Mr. Aubrey Abbott (Minister for Home Affairs), That, in accordance with the provisions of the Commonwealth Public Works Committee Act 1913- 1921, the following proposed work be referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works for investigation and report, viz. -

SC6.13 Planning Scheme Policy – Places of Significance

SC6.13 Planning scheme policy – Places of significance SC6.13.1 Purpose of the planning scheme policy (1) The purpose of this planning scheme policy is to provide guidance on preparing a statement of significance, impact assessment report, archaeological management plan, conservation management plan and an archival report. The planning scheme policy also contains the statements of cultural significance for each of the places of local significance which must be considered when assessing development applications of the place. SC6.13.2 Information Council may request SC6.13.2.1 Guidelines for preparing a Statement of significance (1) An appropriately qualified heritage consultant is to prepare the statement of significance. (2) A statement of cultural significance is to be prepared in accordance with the ICOMOS Burra Charter, 1999 and associated guidelines and the Queensland Government publication, using the criteria – a methodology. (3) The statement of cultural significance describes the importance of a place and the values that make it important. (4) A statement of cultural significance is to include the following: (a) Place details including place name, if the place is known by any other alternative; names and details if it listed on any other heritage registers; (b) Location details including the physical address, lot and plan details, coordinates and the specific heritage boundary details; (c) Statement/s of the cultural significance with specific reference to the cultural significance criteria; (d) A description of the thematic history and context of the place demonstrating an understanding of the history, key themes and fabric of the place within the context of its class; (e) A description of the place addressing the architectural description, locational description and the integrity and condition of the place; (f) Images and plans of the place both current and historical if available; (g) Details of the author/s, including qualifications and the date of the report. -

The Architectural Practice of Gerard Wight and William Lucas from 1885 to 1894

ABPL90382 Minor Thesis Jennifer Fowler Student ID: 1031421 22 June 2020 Boom Mannerism: The Architectural Practice of Gerard Wight and William Lucas from 1885 to 1894 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Urban and Cultural Heritage, Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne Frontispiece: Herbert Percival Bennett Photograph of Collins Street looking east towards Elizabeth Street, c.1894, glass lantern slide, Gosbel Collection, State Library of Victoria. Salway, Wight and Lucas’ Mercantile Bank of 1888 with dome at centre above tram. URL: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/54894. Abstract To date there has been no thorough research into the architectural practice of Wight and Lucas with only a few of their buildings referred to with brevity in histories and articles dealing with late nineteenth-century Melbourne architecture. The Boom era firm of Wight and Lucas from 1885 to 1894 will therefore be investigated in order to expand their catalogue of works based upon primary research and field work. Their designs will be analysed in the context of the historiography of the Boom Style outlined in various secondary sources. The practice designed numerous branches for the Melbourne Savings Bank in the metropolitan area and collaborated with other Melbourne architects when designing a couple of large commercial premises in the City of Melbourne. These Mannerist inspired classical buildings fit the general secondary descriptions of what has been termed the Boom Style of the 1880s and early 1890s. However, Wight and Lucas’ commercial work will be assessed in terms of its style, potential overseas influences and be compared to similar contemporary Melbourne architecture to firstly reveal their design methods and secondly, to attempt to give some clarity to the overall definition of Melbourne’s Boom era architecture and the firm’ place within this period. -

Another Two Diagonal Avenues Intersect the Site, Radiating from the Central Section of the Gardens on Carlton Street, to the Two Southern Entry Points

ROYAL EXHIBITION BUILDING AND CARLTON GARDENS Another two diagonal avenues intersect the site, radiating from the central section of the gardens on Carlton Street, to the two southern entry points. The avenue on the east side is planted with Plane trees (Platanus x acerifolia). Near the Works Depot, in the avenue’s most northern extent, the trees are planted at wide spacings. This may have been a realisation of John Guilfoyle’s 1916 proposal to remove every second plane tree from the South Garden Plane Tree Avenue. It is unclear when the removal was to take place. The plane tree avenue referred to may have been that in the North Garden and not the one in the South Garden. In the southern section the trees are closely spaced, forming a denser over canopy and providing a stronger sense of enclosure. The avenue on the opposite diagonal on the west side of the gardens is planted with Grey Poplars (Populus x canescens) also reaching senescence. A replanting on the south-west side of this avenue with poplars occurred in 2006. The avenue’s integrity is strongest near Carlton Street where the trees are regularly spaced and provide good canopy coverage. 4.4.5 North Garden Boundary Trees The layout of the North Garden in the 1890s was primarily based on extensive avenue plantings crossing the site, with little in the way of other ornamentation. Individual specimen trees were mainly planted around the perimeter of the site, forming loose boundary plantations. The spaces between the avenue plantations remained relatively free of in-fill plantings, with expanses of turf being the primary surface treatment in these areas. -

The Former High Court Building Is Important As the First Headquarters of the High Court of Australia

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: High Court of Australia (former) Other Names: Federal Court Place ID: 105896 File No: 2/11/033/0434 Nomination Date: 13/06/2006 Principal Group: Law and Enforcement Status Legal Status: 15/06/2006 - Nominated place Admin Status: 16/06/2006 - Under assessment by AHC--Australian place Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Melbourne Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): Address: 450 Little Bourke St, Melbourne, VIC 3000 LGA: Melbourne City VIC Location/Boundaries: 450 Little Bourke Street, Melbourne, comprising the whole of Allotment 13B Section 19, City of Melbourne. Assessor's Summary of Significance: The former High Court Building is important as the first headquarters of the High Court of Australia. It operated from 1928 to 1980, a time when many Constitutional and other landmark judicial decisions were made affecting the nation’s social and political life. The whole of the building and its interior design, fitout (including original furniture) and architectural features bear witness to these events. As the first purpose built building for the home of the nation's High Court, it combines the then budgetary austerity of the Commonwealth with a skilled functional layout, where the public entry is separated from the privacy of the Justices’ chambers and the Library by the three central Courts, in a strongly modelled exterior, all viewed as a distinct design entity. The original stripped classical style and the integrity of the internal detailing and fit out of the Courts and Library is overlaid by sympathetic additions with contrasting interior Art Deco design motifs. -

Periodic Report

australian heritage council Periodic Report march 2004 – february 2007 australian heritage council Periodic Report march 2004 – february 2007 Published by the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Water Resources ISBN: 9780642553513 © Commonwealth of Australia 2007 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca Cover images: (left to right): Royal National Park, Ned Kelly’s armour, Old Parliament House, Port Arthur, Nourlangie rock art. © Department of the Environment and Water Resources (and associated photographers). Printed by Union Offset Printers Designed and typeset by Fusebox Design 2 australian heritage council – periodic report The Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister Australian Heritage Council: Periodic Report On 19 February, 2004 the Minister for the Environment and Heritage appointed the Australian Heritage Council (the Council) to act as his principal adviser on heritage matters with roles and responsibilities laid out in the Australian Heritage Council Act 2003 (the AHC Act). Under Section 24A of the AHC Act, Council may prepare a report on any matter related to its functions and provide the report to the Minister for laying before each House of the Parliament within 15 sitting days after the day on which the Minister receives the report. -

Central City (Hoddle Grid) Heritage Review 2011

Central City (Hoddle Grid) Heritage Review 2011 Collie, R & Co warehouse, 194-196 Little Lonsdale Victorian Cricket Association Building (VCA), 76-80 Street, Melbourne 3000 ........................................... 453 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000..............................285 Cavanagh's or Tucker & Co's warehouse, 198-200 Schuhkraft & Co warehouse, later YMCA, and AHA Little Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000 ................... 459 House, 130-132 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000....292 Women's Venereal Disease Clinic, 372-378 Little Cobden Buildings, later Mercantile & Mutual Chambers Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000............................ 466 and Fletcher Jones building, 360-372 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000 .......................................................298 Cleve's Bonded Store, later Heymason's Free Stores, 523-525 Little Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000 ..... 473 Waterside Hotel, 508-510 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000 .........................................................................308 Blessed Sacrament Fathers Monastery, St Francis, 326 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000............................ 479 Coffee Tavern (No. 2), 516-518 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000 .......................................................315 Michaelis Hallenstein & Co building, 439-445 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne 3000 ........................................... 485 Savings Bank of Victoria Flinders Street branch, former, 520-522 Flinders Street, Melbourne 3000....322 Watson's warehouse, later 3LO and 3AR studios, 3AW Radio Theatre, -

20120622 Newstead Database

Shire of Mount Alexander Heritage Study of the Shire of Newstead STAGE 2 Section 3 Heritage Citations: Volume 3 Newstead Wendy Jacobs, Phil Taylor, Robyn Ballinger, Vicki Johnson & Dr David Rowe May 2004 Revised June 2012 .. Table of Contents Page Section 1: The Report Executive Summary i 1.0 Introduction to the Study 1.1 The Study Team 1 1.2 Sections 1 1.3 Acknowledgments 2 1.4 Consultants Brief 2 1.5 The Study Area 3 1.6 Terminology 5 2.0 Methodology 2.1 Stage 1 6 2.2 Stage 2 6 3.0 Scope of Works & Assessment 3.1 Thematic Environmental History 9 3.2 Heritage Places 11 3.2.1 Individual Heritage Places 12 3.2.2 Rural Areas 12 3.2.3 Archaeological Sites 12 3.2.4 Mining Sites 13 3.3 Heritage Precincts 3.3.1 Precinct Evaluation Criteria 19 3.3.2 Campbells Creek Heritage Precinct 21 3.3.3 Fryerstown Heritage Precinct 32 3.3.4 Guildford Heritage Precinct 43 3.3.5 Newstead Heritage Precinct 53 3.3.6 Vaughan Heritage Precinct 68 4.0 Assessment of Significance 4.1 Basis of Assessment Criteria 78 4.2 The Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter (November 1999) 78 4.3 Assessment Criteria utilised in this Study 80 4.4 Levels of Significance 80 5.0 Heritage Program 5.1 Introduction 81 5.2 Heritage Program Recommendations 81 5.2.1 Statutory Registers 81 5.2.2 Mount Alexander Shire Policy review and implementation 82 5.2.3 Recommended Planning Scheme Amendment Process 84 5.2.4 Additional Planning Issues to be considered by Council 86 5.2.5 Council Heritage Incentives 86 5.2.6 Public Awareness Program 87 6.0 Appendices 6.01 The Project Brief 6.02 The Australia -

Victorian Heritage Database Place Details - 30/9/2021 FORMER ROYAL MINT

Victorian Heritage Database place details - 30/9/2021 FORMER ROYAL MINT Location: 280-318 WILLIAM STREET and 391-429 LATROBE STREET and 388-426 LITTLE LONSDALE STREET MELBOURNE, Melbourne City Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number: H0770 Listing Authority: VHR Extent of Registration: AMENDMENT OF REGISTER OF HISTORIC BUILDINGS Historic Building No. 770, former Royal Mint, 280 William Street, Melbourne 3000. (All of the buildings and land shown hatched on the plan hereunder). [Victoria Government Gazette No. G13 28 March 1990 p.932] Statement of Significance: The Former Royal Mint was designed by John James Clark of the Public Works Office. Design work began in 1869 and it was built during 1871-72 by the contractors William Murray and Company of Emerald Hill, and Martin and Peacock of West Melbourne. The complex originally contained coin production facilities, administration and residential quarters and associated structures, but all that remains now are the two-storey office building and residence, two gate-houses, perimeter walling and palisading. The main two storey building is a rendered brick structure on a heavy rusticated base. Unlike the Palladian norm, the piano nobile is on the ground floor. The first floor features paired ionic columns, while an attic storey features oval windows. The perimeter wall is an imposing brick construction with large wrought iron gates and iron lamps. 1 The Former Royal Mint is of historical and architectural significance to the State of Victoria. The Former Royal Mint is of historical significance because of its important role in the economic, financial and political development of Victoria for nearly 100 years.