The Architectural Practice of Gerard Wight and William Lucas from 1885 to 1894

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Symposium

Xl. ve XVIII. yüzyıllar Xl. to XVIII. centuries iSLAM-TÜRK MEDENiYETi VE AVRUPA ISLAMIC-TURKISH CIVILIZATION AND EUROPE Uluslararası Sempozyum International Symposium iSAM Konferans Salonu !SAM Conference Hall Xl. ve XVIII. yüzyıllar islam-Türk Medaniyeti ve Avrupa ULUSLARARASISEMPOZYUM 24-26 Kas1m, 2006 · • Felsefe - Bilim • Siyaset- Devlet • Dil - Edebiyat - Sanat • Askerlik • Sosyal Hayat •Imge fl,cm. No: Tas. No: Organizasyon: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı islam Araştırmaları Merkezi (iSAM) T.C. Diyanet işleri Başkanlığı Marmara Üniversitesi ilahiyat Fakültesi © Kaynak göstermek için henüz hazır değildir. 1 Not for quotation. ,.1' Xl. ve XVIII. yüzyıllar Uluslararası Sempozyum DIFFERING ATTITUDES OF A FEW EUROPEAN SCHOLARS AND TRAVELLERS TOWARDS THE REMOVAL OF ARTEFACTS FROM THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE Fredrik THOMASSON• The legitimacy of removal of artefacts from the Ottoman Empire during the Iate 181h and early 191h century was already debated by contemporary observers. The paper presents a few Swedish scholars/travellers and their views on the dismemberment of the Parthenon, exeavation of graves ete. in the Greek and Egyptian territories of the Empire. These scholars are often very critica! and their opinions resemble to a great extent many of the positions in today's debate. This is contrasted with views from representatives from more in:fluential countries who seem to have fewer qualms about the whotesale removal of objects. The possible reasons for the difference in opinions are discussed; e.g. how the fact of being from a sınaller nation with less negotiating and economic power might influence the opinions of the actors. The main characters are Johan David Akerblad (1763-1819) orientalist and classical scholar, the diplomat Erik Bergstedt (1760-1829) and the language scholar Jacob Berggren (1790-1868). -

Hoock Empires Bibliography

Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination: Politics, War, and the Arts in the British World, 1750-1850 (London: Profile Books, 2010). ISBN 978 1 86197. Bibliography For reasons of space, a bibliography could not be included in the book. This bibliography is divided into two main parts: I. Archives consulted (1) for a range of chapters, and (2) for particular chapters. [pp. 2-8] II. Printed primary and secondary materials cited in the endnotes. This section is structured according to the chapter plan of Empires of the Imagination, the better to provide guidance to further reading in specific areas. To minimise repetition, I have integrated the bibliographies of chapters within each sections (see the breakdown below, p. 9) [pp. 9-55]. Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination (London, 2010). Bibliography © Copyright Holger Hoock 2009. I. ARCHIVES 1. Archives Consulted for a Range of Chapters a. State Papers The National Archives, Kew [TNA]. Series that have been consulted extensively appear in ( ). ADM Admiralty (1; 7; 51; 53; 352) CO Colonial Office (5; 318-19) FO Foreign Office (24; 78; 91; 366; 371; 566/449) HO Home Office (5; 44) LC Lord Chamberlain (1; 2; 5) PC Privy Council T Treasury (1; 27; 29) WORK Office of Works (3; 4; 6; 19; 21; 24; 36; 38; 40-41; 51) PRO 30/8 Pitt Correspondence PRO 61/54, 62, 83, 110, 151, 155 Royal Proclamations b. Art Institutions Royal Academy of Arts, London Council Minutes, vols. I-VIII (1768-1838) General Assembly Minutes, vols. I – IV (1768-1841) Royal Institute of British Architects, London COC Charles Robert Cockerell, correspondence, diaries and papers, 1806-62 MyFam Robert Mylne, correspondence, diaries, and papers, 1762-1810 Victoria & Albert Museum, National Art Library, London R.C. -

CITY of BOROONDARA Review of B-Graded Buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn

CITY OF BOROONDARA Review of B-graded buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn Prepared for City of Boroondara January 2007 Revised June 2007 VOLUME 4 BUILDINGS NOT RECOMMENDED FOR THE HERITAGE OVERLAY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 Main Report VOLUME 2 Individual Building Data Sheets – Kew VOLUME 3 Individual Building Data Sheets – Camberwell and Hawthorn VOLUME 4 Individual Building Data Sheets for buildings not recommended for the Heritage Overlay LOVELL CHEN 1 Introduction to the Data Sheets The following data sheets have been designed to incorporate relevant factual information relating to the history and physical fabric of each place, as well as to give reasons for the recommendation that they not be included in the Schedule to the Heritage Overlay in the Boroondara Planning Scheme. The following table contains explanatory notes on the various sections of the data sheets. Section on data sheet Explanatory Note Name Original and later names have been included where known. In the event no name is known, the word House appears on the data sheet Reference No. For administrative use by Council. Building type Usually Residence, unless otherwise stated. Address Address as advised by Council and checked on site. Survey Date Date when site visited. Noted here if access was requested but not provided. Grading Grading following review (C or Ungraded). In general, a C grading reflects a local level of significance albeit a comparatively low level when compared with other examples. In some cases, such buildings may not have been extensively altered, but have been assessed at a lower level of local significance. In other cases, buildings recommended to be downgraded to C may have undergone alterations or additions since the earlier heritage studies. -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 As a Masterpiece of Late Gothic Architecture

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 as a masterpiece of late Gothic architecture. The church’s reputation was strong enough of the time for it to be chosen as the location for a young Louis XIV to receive communion. Mozart also Church of Saint 2 Impasse Saint- chose the sanctuary as the location for his mother’s funeral. Among ** Unknown Eustace Eustache those baptised here as children were Richelieu, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, future Madame de Pompadour and Molière, who was also married here in the 17th century. Amazing façade. Mon-Fri (9.30am-7pm), Sat-Sun (9am-7pm) Japanese architect Tadao Ando has revealed his plans to convert Paris' Bourse de Commerce building into a museum that will host one of the world's largest contemporary art collections. Ando was commissioned to create the gallery within the heritage-listed building by French Bourse de Commerce ***** Tadao Ando businessman François Pinault, who will use the space to host his / Collection Pinault collection of contemporary artworks known as the Pinault Collection. A new 300-seat auditorium and foyer will be set beneath the main gallery. The entire cylinder will be encased by nine-metre-tall concrete walls and will span 30 metres in diameter. Opening soon The Jardin du Palais Royal is a perfect spot to sit, contemplate and picnic between boxed hedges, or shop in the trio of beautiful arcades that frame the garden: the Galerie de Valois (east), Galerie de Montpensier (west) and Galerie Beaujolais (north). However, it's the southern end of the complex, polka-dotted with sculptor Daniel Buren's Domaine National du ***** 8 Rue de Montpensier 260 black-and-white striped columns, that has become the garden's Palais-Royal signature feature. -

Architecture: the Museum As Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12

Architecture: The Museum as Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12 Program Outline & Volunteer Resource Package Single Visit Program Option : 2 HOURS Contents of Resource Package Contents Page Program Development & Description 1 Learning Objectives for Students & Preparation Guidelines 2 One Page Program Outline 3 Powerpoint Presentation Overview 4 - 24 Glossary – Architectural Terms 24 - 27 Multimedia Resource Lists (Potential Research Activities) 27 - 31 Field Journal Sample 32 - 34 Glossary – Descriptive Words Program Development This programme was conceived in conjunction with the MOA Renewal project which expanded the Museum galleries, storages and research areas. The excitement that developed during this process of planning for these expanded spaces created a renewed enthusiasm for the architecture of Arthur Erickson and the landscape architecture of Cornelia Oberlander. Over three years the programme was developed with the assistance of teacher specialists, Jane Kinegal, Cambie Secondary School and Russ Timothy Evans, Tupper Secondary School. This programme was developed under the direction of Jill Baird, Curator of Education & Public Programmes, with Danielle Mackenzie, Public Programs & Education Intern 2008/09, Jennifer Robinson, Public Programs & Education Intern 2009/10, Vivienne Tutlewski, Public Programs & Education Intern 2010/2011, Katherine Power, Public Programs & Education Workstudy 2010/11, and Maureen Richardson, Education Volunteer Associate, who were all were key contributors to the research, development and implementation of the programme. Program Description Architecture: The Museum as Muse, Grades 6 - 12 MOA is internationally recognized for its collection of world arts and culture, but it is also famous for its unique architectural setting. This program includes a hands-on phenomenological (sensory) activity, an interior and exterior exploration of the museum, a stunning visual presentation on international museum architecture, and a 30 minute drawing activity where students can begin to design their own museum. -

Dissertation, Full Draft V. 3

Inventing Architectural Identity: The Institutional Architecture of James Renwick, Jr., 1818-95 Nicholas Dominick Genau Amherst, New York BA, University of Virginia, 2006 MA, University of Virginia, 2009 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McIntire Department of Art University of Virginia May, 2014 i TABLE OF CONTENTS ! ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .......................................................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1! An Architectural Eclectic:!! A Survey of the Career of James Renwick, Jr. .......................................................................................................................................................... 9! CHAPTER 2! “For the Dignity of Our Ancient and Glorious Catholic Name”:!! Renwick and Archbishop Hughes!at St. Patrick’s Cathedral ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill

Marc Fehlmann A Building from which Derived "All that is Good": Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2005) Citation: Marc Fehlmann, “A Building from which Derived ‘All that is Good’: Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2005), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn05/207-a- building-from-which-derived-qall-that-is-goodq-observations-on-the-intended-reconstruction- of-the-parthenon-on-calton-hill. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2005 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Fehlmann: A Building from which Derived "All that is Good" Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2005) A Building from which Derived "All that is Good": Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill by Marc Fehlmann When, in 1971, the late Sir Nikolaus Pevsner mentioned the uncompleted National Monument at Edinburgh in his seminal work A History of Building Types, he noticed that it had "acquired a power to move which in its complete state it could not have had."[1] In spite of this "moving" quality, this building has as yet not garnered much attention within a wider scholarly debate. Designed by Charles Robert Cockerell in the 1820's on the summit of Calton Hill to house the mortal remains of those who had fallen in the Napoleonic Wars, it ended as an odd ruin with only part of the stylobate, twelve columns and their architrave at the West end completed in its Craigleith stone (fig. -

Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group

WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Illustration credits and copyright references for photographs, maps and other illustrations are under negotiation with the following organisations: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster School Parliamentary Estates Directorate Westminster City Council English Heritage Greater London Authority Simmons Aerofilms / Atkins Atkins / PLB / Barry Stow 2 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St. Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site Management Plan Prepared on behalf of the Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, by a consortium led by Atkins, with Barry Stow, conservation architect, and tourism specialists PLB Consulting Ltd. The full steering group chaired by English Heritage comprises representatives of: ICOMOS UK DCMS The Government Office for London The Dean and Chapter of Westminster The Parliamentary Estates Directorate Transport for London The Greater London Authority Westminster School Westminster City Council The London Borough of Lambeth The Royal Parks Agency The Church Commissioners Visit London 3 4 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE S I T E M ANAGEMENT PLAN FOREWORD by David Lammy MP, Minister for Culture I am delighted to present this Management Plan for the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site. For over a thousand years, Westminster has held a unique architectural, historic and symbolic significance where the history of church, monarchy, state and law are inexorably intertwined. As a group, the iconic buildings that form part of the World Heritage Site represent masterpieces of monumental architecture from medieval times on and which draw on the best of historic construction techniques and traditional craftsmanship. -

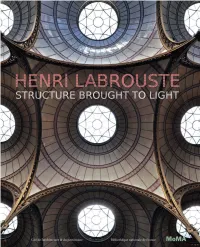

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light Is the Condensed Result of Several Years of Research, Goers Are Plunged

HENRI LABROUSTE STRUCTURE BROUGHT TO LIGHT With essays by Martin Bressani, Marc Grignon, Marie-Hélène de La Mure, Neil Levine, Bertrand Lemoine, Sigrid de Jong, David Van Zanten, and Gérard Uniack The Museum of Modern Art, New York In association with the Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine et the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the special participation of the Académie d’architecture and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. This exhibition, the first the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine has devoted to Since its foundation eighty years ago, MoMA’s Department of Architecture (today the a nineteenth-century architect, is part of a larger series of monographs dedicated Department of Architecture and Design) has shared the Museum’s linked missions of to renowned architects, from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau to Claude Parent and showcasing cutting-edge artistic work in all media and exploring the longer prehistory of Christian de Portzamparc. the artistic present. In 1932, for instance, no sooner had Philip Johnson, Henry-Russell Presenting Henri Labrouste at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine carries with Hitchcock, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., installed the Department’s legendary inaugural show, it its very own significance, given that his name and ideas crossed paths with our insti- Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, than plans were afoot for a show the following tution’s history, and his works are a testament to the values he defended. In 1858, he year on the commercial architecture of late-nineteenth-century Chicago, intended as the even sketched out a plan for reconstructing the Ecole Polytechnique on Chaillot hill, first in a series of shows tracing key episodes in the development of modern architecture though it would never be followed through. -

310 Charles Robert Cockerell's Formation of Architectural Principles

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand Vol. 32 Edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan Published in Sydney, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2015 ISBN: 978 0 646 94298 8 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Kohane, Peter. “Charles Robert Cockerell’s Formation of Architectural Principles.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions and Change, edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan, 310-318. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015. Peter Kohane, UNSW Australia Charles Robert Cockerell’s Formation of Architectural Principles In contributing to the conference theme of the ‘history of architectural and design education’, this paper focuses on an aspect of Charles Robert Cockerell’s career, which is the genesis of design principles, most significantly the human analogy. The architect’s early ideas are worthy of consideration, because they remained vital to his mature work as Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy in London. When lecturing at this institution from 1841 to 1856, he set out principles that had a significant impact on architects in Britain. Cockerell’s initial concepts will be identified in statements about sculptures and buildings, which were studied when travelling in Greece, Asia Minor and Italy. His responses to renowned ancient Greek and Renaissance works were recorded in letters and diaries. These offer insight into a principle, in which an architect imitates the ‘human form divine’ and historical monuments. Cockerell was especially impressed by the representation of human vitality in Greek figure sculptures, as well as the delicate curved line of a column. -

Cloud Download

1 Contents 4 Welcome 6 Jury Members 2017 9 Horbury Hunt Commercial Award 19 Horbury Hunt Residential Award 33 Bruce Mackenzie Landscape Award 43 Kevin Borland Masonry Award 53 Robin Dods Roof Tile Excellence Award 62 Horbury Hunt Commercial Award Entrants Index 62 Horbury Hunt Residential Award Entrants Index 63 Bruce Mackenzie Landscape Award Entrants Index 64 Kevin Borland Masonry Award Entrants Index 64 Robin Dods Roof Tile Excellence Award Entrants Index editor elizabeth mcintyre creative director sally woodward art direction natasha simmons 2 3 Welcome This year marks the eleventh Think Brick Awards – This year’s winners are to be congratulated for their celebrating outstanding architecture and the use imagination, skill and craftsmanship. I hope these of clay brick, concrete masonry and roof tiles in projects ignite your creativity and encourage the contemporary Australian design. Each year, the entries creation of your own designs championing the build on inspiration taken from the previous cohort of use of brick, block, pavers and roof tiles. finalists to present exemplary projects that use these materials in new and exciting ways. The 2017 finalists provide solutions to low-density elizabeth mcintyre housing, a variety of roof systems and landscape group ceo sanctuaries for the home. These innovative projects think brick, cmaa, rtaa show that masonry is being included increasingly in residential and commercial interiors, as well as to create clever connections between indoor and outdoor spaces. Glazed bricks continue to be featured as standout elements in all types of works, particularly in urban design. IS PIERCINGCreativity THE MUNDANE to find the marvelous.- Bill Moyers 5 4 5 cameron bruhn ben green debbie–lyn ryan alexis sanal murat sanal emma williamson elizabeth mcintyre architecture media tzannes mcbride charles ryan sanalarc sanalarc coda think brick Cameron Bruhn is the editorial director at Ben has worked on a large number of significant Debbie Ryan is the founding owner of McBride Alexis Sanal is a co-founder of SANALarc.