Religious Self-Fashioning As a Motive in Early Modern Diary Keeping: the Evidence of Lady Margaret Hoby's Diary 1599-1603, Travis Robertson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rıchard Hooker: an Introductıon to Hıs Lıfe and Thought Torrance KIRBY

İslâmÎ İlİmler derGİsİ, yıl 11 cİlt 11 sayı 2 Güz 2016 (69/81) rıchard hOOker: an ıntrOductıOn tO hıs lıfe and thOuGht Torrance KIRBY, McGill University, Montreal, Canada Abstract Richard Hooker (1554-1600) Richard Hooker was born in Devon, near Exeter in April 1554; he died at Bishopsbourne, Kent on 2 November 1600. From 1579 to 1585 he was a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and read the Hebrew Lecture at the University during this period. In 1585 Queen Elizabeth I appointed him Master of the Temple Church at the Inns of Court where he engaged in a preaching struggle with his assistant, Walter Travers. Their disagreement over the theological and political assumptions of the reformed Church of England as defined by the Act of Uniformity of 1559 and the Book of Common Prayer led to Hooker’s composition of his great work Of the Lawes of Ecclesiasticall Politie (1593). The treatise consists of a lengthy preface which frames the polemical context, fol- lowed by eight books. The first four books address what he terms “gen- eral meditations”: (1) the nature of law in general, (2) the proper uses of the authorities of reason and revelation, (3) the application of the latter to the government of the church and (4) objections to practices inconsistent with the continental “reformed” example. The final four address the more “particular decisions” of the Church’s constitution: (5) public religious duties as prescribed by the Book of Common Prayer (1559), (6) the power of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, (7) the authority of bishops and (8) the supreme authority of the Prince in both church and commonwealth, and hence their unity in the Christian state. -

The Empty Tomb

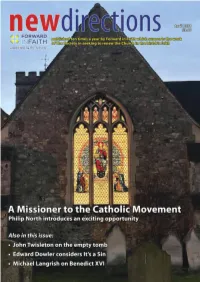

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

The History of the North Beach Sub-Branch 1945 – 1991

HISTORY OF NORTH BEACH SUB-BRANCH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 1945 to 1991 Original Edition was Edited by Joe W. HARRIS and Compiled by Ron E. TOMLINSON This Edition of The History of the North Beach Sub-Branch of RSLWA 1945 to 1991 has not altered, or added to, that originally published. No attempt has been made to edit the content, as it reflects original input and recollections of the members of the Sub-Branch. It has however been reformatted to provide the Sub-Branch with a digital copy in a form that can be distributed to members or added to should the Sub-Branch choose. Brian Jennings Member North Beach Sub-Branch RSLWA July 2020 © North Beach Sub-Branch of the RSLWA 2020 2 PREFACE This history makes no pretence of being founded on actual records until early 1962, as all minutes of meetings from the foundation date were burnt in a fire that destroyed the then Secretary's shed. It has been compiled up to that time from the memory of early members. In most cases over 45 years have elapsed since the members joined the Sub-Branch and many are 75 years old and over. You will therefore appreciate their difficulty in recalling names and dates accurately. Over the last five years I have been urged by the long -term members to put together this History but have lacked the facilities and the know how to complete the task. When Joe Harris joined the Sub-Branch and later published a book to enlighten his family on his service in the Army, I approached him to assist the Sub-Branch with the use of his computer, to produce this History. -

Life and Letters of Brooke Foss Westcott Vol. I

ST. mars couKE LIFE AND LETTERS OF BROOKE FOSS WESTCOTT Life and Letters of Foss Westcott Brooke / D.D., D.C.L. Sometime Bishop of Durham BY HIS SON ARTHUR WESTCOTT WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I 117252 ILonfcon MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1903 Ail rights reserved "To make of life one harmonious whole, to realise the invisible, to anticipate the transfiguring majesty of the Divine Presence, is all that is worth living for." B. F. \V. FRATRI NATU MAXIMO DOMUS NOSTRAE DUCI ET SIGNIFERO PATERNI NOMINIS IMPRIMIS STUDIOSO ET AD IPSIUS MEMORIAM SI OTIUM SUFFECISSET PER LITTERAS CELEBRANDAM PRAETER OMNES IDONEO HOC OPUSCULUM EIUS HORTATU SUSCEPTUM CONSILIIS AUCTUM ATQUE ADIUTUM D. D. D. FRATER NATU SECUNDUS. A. S., MCMIII. FRATKI NATU MAXIMO* 11ace tibi in re. ai<-o magni monnmcnta Parent is Maioi'i natu, frater, amo re pari. Si<jui'i inest dignnni, lactabere ; siquid ineptnm, Non milii tn censor sed, scio, [rater eris. Scis boif qnam duri fnerit res ilia laboris, Qnae melius per te suscipienda fiiit. 1 Tie diex, In nobis rcnoi'ali iwiinis /icres, Agtniw's ct nostri signifer unus eras. Scribcndo scd enim spatiiim, tibi sorte ncgatum, Iniporlnna minus fata dedcre mihi : Rt levin.: TISUDI cst infabrius arnia tulisse (Juain Patre pro tanto nil voluisse pati. lament: opus exaction cst quod, te sitadcnte, siibivi . Aecipc : indicia stctque cadatqne tno. Lcctorurn hand dnbia cst, reor, indulgentia. ; nalo Quodfrater frat ri tu dabis, ilia dabit. Xcc pctinins landcs : magnani depingerc vitani Ingcnio fatcor grandins ess.: nieo. Hoc erat in votis, nt, nos quod atnavinms, Hind Serns in cxtcrnis continnaret amor. -

Resourcing Sustainable Church: a Time to Change - Together

RESOURCING SUSTAINABLE CHURCH: A TIME TO CHANGE - TOGETHER Transforming lives in Greater Lincolnshire 1 Foreword from The Bishop of Lincoln Returning to Lincoln after almost two years’ absence gives me the opportunity to see and evaluate the progress that has been made to address the issues we face as a diocese. Many of the possibilities that are placed before you in this report were already under discussion in 2019. What this report, and the work that lies behind it, does is to put flesh on the bones. It gives us a diocese the opportunity to own up to and address the issues we face at this time. I am happy strongly to recommend this report. It comes with my full support and gratitude to those who have contributed so far. What it shows is that everything is possible if we trust in God and each other. Of course, this is only a first step in a process of development and change. Much as some of us, including me at times, might like to look back nostalgically to the past – the good news is that God is calling us into something new and exciting. What lies ahead will not be easy – as some hard decisions will need to be taken. But my advice is that there will never be a better opportunity to work together to uncover and build the Kingdom of God in Greater Lincolnshire. I urge the people of God in this diocese to join us on this journey. +Christopher Lincoln: Bishop of Lincoln 2 Introduction Resourcing Sustainable Church: A Time to Change - Together sets a vision for a transformed church. -

The Reception of Hobbes's Leviathan

This is a repository copy of The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/71534/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Parkin, Jon (2007) The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. In: Springborg, Patricia, (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes's Leviathan. The Cambridge Companions to Philosophy, Religion and Culture . Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 441-459. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521836670.020 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ jon parkin 19 The Reception of Hobbes’s Leviathan The traditional story about the reception of Leviathan was that it was a book that was rejected rather than read seriously.1 Leviathan’s perverse amalgamation of controversial doctrine, so the story goes, earned it universal condemnation. Hobbes was outed as an athe- ist and discredited almost as soon as the work appeared. Subsequent criticism was seen to be the idle pursuit of a discredited text, an exer- cise upon which young militant churchmen could cut their teeth, as William Warburton observed in the eighteenth century.2 We need to be aware, however, that this was a story that was largely the cre- ation of Hobbes’s intellectual opponents, writers with an interest in sidelining Leviathan from the mainstream of the history of ideas. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

The Legacy of Thomas Valpy French

The Legacy of Thomas Valpy French Vivienne Stacey ew seem to have heard of this self-effacing man, Thomas service abroad. Soon after this Lea was fatally injured in a railway F Valpy French. However, Bishop Stephen Neill described accident. Their mutual decision bound French even more and he him as the most distinguished missionary who has ever served applied to the CMS. the Church Missionary Society (CMS).1 For those concerned with There was one other matter to be resolved before he and his communicating the gospel to Muslims, his legacy is especially companion, Edward Stuart, sailed in 1850 for India. Thomas was precious. attracted to M. A. Janson, daughter of Alfred Janson of Oxford. Twice her parents refused permission to Thomas to pursue his The Life of French (1825-1891) suit even by correspondence. According to the custom of the day, he accepted this, though very reluctantly.i Then suddenly Alfred Thomas Valpy French was born on New Year's Day 1825, the Janson withdrew his objections and Thomas was welcomed by first child of an evangelical Anglican clergyman, Peter French, the family. He became engaged to the young woman shortly who worked in the English Midlands town of Burton-on-Trent before he sailed." A year later she sailed to India to be married for forty-seven years. In those days before the Industrial Revo to him. Throughout- his life, she was a strong, quiet support to lution, Burton-on Trent was a small county town. Thomas liked him. The health and educational needs of their eight children walking with his father to the surrounding villages where Peter sometimes necessitated long periods of separation for the parents. -

A Study of the Leadership Provided by Successive Archbishops of Perth in the Recruitment and Formation of Clergy in Western Australia 1914-2005

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-2005 Six Archbishops and their ordinands: A study of the leadership provided by successive Archbishops of Perth in the recruitment and formation of clergy in Western Australia 1914-2005 Brian Kyme Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kyme, B. (2005). Six Archbishops and their ordinands: A study of the leadership provided by successive Archbishops of Perth in the recruitment and formation of clergy in Western Australia 1914-2005. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/631 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/631 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Select List 38. Question Is Shall the Right Reverend Francis De Witt Batty, M. A., Bishop of Newcastle, Be P

Select List 38. Question is shall the Right Reverend Francis de Witt Batty, M. A., Bishop of Newcastle, be placed on the Select List? 39. Proposed by Rev Dr. Micklem, seconded by Mr C. H. G. Simpson, supported by Sir Albert Gould, Chancellor. 40. Vote taken. 41. The Right Reverend Francis de Witt Batty is not placed on the Select List. 42. The question is shall the Reverend Thomas Walter Gilbert, M.A., D.D., Principal of St. John's Hall, Highbury, be placed on the Select List? 43. Proposed by Archdeacon Charlton, seconded by Mr T. S. Holt. 44. Mr H. L. Tress said that information had been received that he is uncertain that he will even consider the nomination. 45. Vote taken. 46. The Reverend Dr. Gilbert is not placed on the Select List. 47. The question is shall the Reverend Arthur Rowland Harry Grant, D.D., C.V.O., M.V.O., Canon Residentiary in Norwich Cathedral, be placed on the Select List? 48. Proposed by Rev S. H. Denman, seconded by Mr H. L. Tress, supported by Rev Stanley Howard and Canon H. S. Begbie. 49. Vote taken. 50. The Rev Canon Grant, D.D., is placed on the Select List. 51. The question is, shall the Reverend Laurence William Grensted, D.D., Canon of Liverpool Cathedral, be placed on the Select List? 52. Proposed by Rev Dixon Hudson; seconded by Rev H. N. Baker; supported by Rev G. C. Glanville, Rev C.' T. Parkinson, Rev L. N. Sutton and Canon Garnsey. 53. Vote taken. 54. -

No. 3 March 2014

No. 3 March 2014 Newsletter of the Religious History Association TheRHA: Newsletter of the Religious History Association March 2014 http:// www.therha.com.au CONTENTS PRESIDENT’S REPORT 1 JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS HISTORY: EDITORS’ REPORT 3 CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTS: NEW ZEALAND 5 VICTORIA 6 QUEENSLAND 12 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 12 MACQUARIE 14 TASMANIA 17 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 19 UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 20 AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY – CENTRE FOR EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES 29 AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY – GOLDING CENTRE 31 SYDNEY COLLEGE OF DIVINITY RESEARCH REPORT 33 SUBSCRIPTION AND EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES 36 OFFICE BEARERS 37 Cover photographs: Sent in by Carole M. Cusack: Ancient Pillar, Sanur, Bali (photographed by Don Barrett, April 2013) Astronomical Clock, Prague (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prague_astronomical_clock) Europe a Prophecy, (frontispiece, also known as The Ancient of Days) printed 1821 by William Blake, The Ancient of Days is the title of a design by William Blake, originally published as the frontispiece to a 1794 work, Europe a Prophecy. (http://www.blakearchive.org/exist/blake/archive/biography.xq?b=biography&targ_div=d1) Madonna Della Strada (Or Lady of the Way) the original – Roma, Chiesa Del SS. Nome Di Gesù All’Argentina The image of The Virgin before whom St Ignatius prayed and entrusted the fledgling Society of Jesus. (http://contemplatioadamorem.blogspot.com.au/2006/12/restored-image-of-madonna-della-strada.html). The Religious History Association exists for the following objects: to promote and advance the study of religious history in Australia to promote the study of all fields of religious history to encourage research in Australian religious history to publish the Journal of Religious History TheRHA: Newsletter of the Religious History Association March 2014 http:// www.therha.com.au Religious History Association - President’s Report for 2013 2103 has seen some changes on the executive as various office-bearers have moved on after a period of considerable service.