Animacy, Symbolism, and Feathers from Mantle's Cave, Colorado By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Possibilities of Osteology in Historical Sarni Archaeology Th Life and Livelihood at the 18 -Century Ohcejohka Sarni Market Site

The possibilities of osteology in historical Sarni archaeology th Life and livelihood at the 18 -century Ohcejohka Sarni market site Eeva-Kristiina Harlin Giellagas Institute, Porotie 12, Fl- 99950 Karigasniemi, Finland Abstract The Ohcejohka market site This paper presents the archaeological material The Ohcejohka market site is well known from from a historical Sarni market site in Ohcejohka. written sources. In the past, it was the central The site was in use already in 1640 when annual place for the Ohcejohka siida (Lapp village), markets were held in the area, and the Ohcejoh- and annual markets were held there at the end ka church was erected at the site in 1701. The of February already in 1640. Due to the colonial excavated material derives from two traditional policy of the Swedish crown, the Ohcejohka and Sarni huts, goahti. The find material is quite typi- Guovdageaidnu churches were erected in 1701, cal for l ?1"- l 9th-century Sarni sites, and the main and even today the new Ohcejohka church, find group consists of unburned animal bones. erected between 1850 and 1853, is situated near The animal bones are analysed and questions of the site (ltkonen 1948 I: 206- 208, 303; 1948 II: livelihood are discussed. 59, 203). Additionally, there is an old sacristy and cemetery at the site and a historical road Keywords: to the Norwegian coast passes through the area Sarni studies, osteology, ethnoarchaeology, his- (Karjalainen 2003). torical archaeology, reindeer. During the winter markets, both live reindeer and reindeer products were sold by the Sarni and traded with burghers coming from southern Introduction towns. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Bioarchaeology (Anthropological Archaeology) - Mario ŠLAUS

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Bioarchaeology (Anthropological Archaeology) - Mario ŠLAUS BIOARCHAEOLOGY (ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHAEOLOGY) Mario ŠLAUS Department of Archaeology, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zagreb, Croatia. Keywords: Bioarchaeology, archaeological, forensic, antemortem, post-mortem, perimortem, traumas, Cribra orbitalia, Harris lines, Tuberculosis, Leprosy, Treponematosis, Trauma analysis, Accidental trauma, Intentional trauma, Osteological, Degenerative disease, Habitual activities, Osteoarthritis, Schmorl’s nodes, Tooth wear Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. Definition of Bioarchaeology 1.2. History of Bioarchaeology 2. Analysis of Skeletal Remains 2.1. Excavation and Recovery 2.2. Human / Non-Human Remains 2.3. Archaeological / Forensic Remains 2.4. Differentiating between Antemortem/Postmortem/Perimortem Traumas 2.5. Determination of Sex 2.6. Determination of Age at Death 2.6.1. Age Determination in Subadults 2.6.2. Age Determination in Adults. 3. Skeletal and dental markers of stress 3.1. Linear Enamel Hypoplasia 3.2. Cribra Orbitalia 3.3. Harris Lines 4. Analyses of dental remains 4.1. Caries 4.2. Alveolar Bone Disease and Antemortem Tooth Loss 5. Infectious disease 5.1. Non–specific Infectious Diseases 5.2. Specific Infectious Disease 5.2.1. Tuberculosis 5.2.2. Leprosy 5.2.3. TreponematosisUNESCO – EOLSS 6. Trauma analysis 6.1. Accidental SAMPLETrauma CHAPTERS 6.2. Intentional Trauma 7. Osteological and dental evidence of degenerative disease and habitual activities 7.1. Osteoarthritis 7.2. Schmorl’s Nodes 7.3. Tooth Wear Caused by Habitual Activities 8. Conclusion Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Bioarchaeology (Anthropological Archaeology) - Mario ŠLAUS 1. Introduction 1.1. Definition of Bioarchaeology Bioarchaeology is the study of human biological remains within their cultural (archaeological) context. -

Ancient DNA from Chalcolithic Israel Reveals the Role of Population Mixture in Cultural Transformation

Corrected: Publisher correction ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05649-9 OPEN Ancient DNA from Chalcolithic Israel reveals the role of population mixture in cultural transformation Éadaoin Harney1,2,3, Hila May4,5, Dina Shalem6, Nadin Rohland2, Swapan Mallick2,7,8, Iosif Lazaridis2,3, Rachel Sarig5,9, Kristin Stewardson2,8, Susanne Nordenfelt2,8, Nick Patterson7,8, Israel Hershkovitz4,5 & David Reich2,3,7,8 1234567890():,; The material culture of the Late Chalcolithic period in the southern Levant (4500–3900/ 3800 BCE) is qualitatively distinct from previous and subsequent periods. Here, to test the hypothesis that the advent and decline of this culture was influenced by movements of people, we generated genome-wide ancient DNA from 22 individuals from Peqi’in Cave, Israel. These individuals were part of a homogeneous population that can be modeled as deriving ~57% of its ancestry from groups related to those of the local Levant Neolithic, ~17% from groups related to those of the Iran Chalcolithic, and ~26% from groups related to those of the Anatolian Neolithic. The Peqi’in population also appears to have contributed differently to later Bronze Age groups, one of which we show cannot plausibly have descended from the same population as that of Peqi’in Cave. These results provide an example of how population movements propelled cultural changes in the deep past. 1 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. 2 Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA. 3 The Max Planck–Harvard Research Center for the Archaeoscience of the Ancient Mediterranean, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. -

Carpals and Tarsals of Mule Deer, Black Bear and Human: an Osteology Guide for the Archaeologist

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2009 Carpals and tarsals of mule deer, black bear and human: an osteology guide for the archaeologist Tamela S. Smart Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Smart, Tamela S., "Carpals and tarsals of mule deer, black bear and human: an osteology guide for the archaeologist" (2009). WWU Graduate School Collection. 19. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/19 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASTER'S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master's degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWu. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. I acknowledge that I retain ownership rights to the copyright of this work, including but not limited to the right to use all or part of this work in future works, such as articles or books. -

Early Farmers from Across Europe Directly Descended from Neolithic Aegeans

Early farmers from across Europe directly descended from Neolithic Aegeans Zuzana Hofmanováa,1, Susanne Kreutzera,1, Garrett Hellenthalb, Christian Sella, Yoan Diekmannb, David Díez-del-Molinob, Lucy van Dorpb, Saioa Lópezb, Athanasios Kousathanasc,d, Vivian Linkc,d, Karola Kirsanowa, Lara M. Cassidye, Rui Martinianoe, Melanie Strobela, Amelie Scheua,e, Kostas Kotsakisf, Paul Halsteadg, Sevi Triantaphyllouf, Nina Kyparissi-Apostolikah, Dushka Urem-Kotsoui, Christina Ziotaj, Fotini Adaktylouk, Shyamalika Gopalanl, Dean M. Bobol, Laura Winkelbacha, Jens Blöchera, Martina Unterländera, Christoph Leuenbergerm, Çiler Çilingiroglu˘ n, Barbara Horejso, Fokke Gerritsenp, Stephen J. Shennanq, Daniel G. Bradleye, Mathias Curratr, Krishna R. Veeramahl, Daniel Wegmannc,d, Mark G. Thomasb, Christina Papageorgopoulous,2, and Joachim Burgera,2 aPalaeogenetics Group, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, 55099 Mainz, Germany; bDepartment of Genetics, Evolution, and Environment, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Biology, University of Fribourg, 1700 Fribourg, Switzerland; dSwiss Institute of Bioinformatics, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; eMolecular Population Genetics, Smurfit Institute of Genetics, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; fFaculty of Philosophy, School of History and Archaeology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; gDepartment of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S1 4ET, United Kingdom; hHonorary Ephor of Antiquities, Hellenic Ministry of Culture & Sports, -

Project Summary Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit

Project Summary Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit Project Title: Landscape Condition Analysis, Dinosaur National Monument—Uintah County, UT and Moffat County, CO Discipline: Natural Type of Project: Technical Assistance Funding Agency: National Park Service Other Partners/Cooperators: University of Wyoming Effective Dates: 7/10/2010– 3/31/2014 Funding Amount: $48,900 Investigators and Agency Representative: NPS Contact: Tamara Naumann, Botanist, Dinosaur National Monument, 4545 E Highway 40, Dinosaur, CO 81610, Tel.: 970-374-3051, Fax.: 970-374-3059, Email: [email protected] Investigator: William L. Baker, Professor, Dept. of Geography, Dept. 3371, 1000 E. University Ave., University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071, Tel.: 307-766-2925, Fax.: 307-766-3294, Email: [email protected] Project Abstract: Dinosaur National Monument is a 211,000 acre park located on the northeastern edge of the Colorado Plateau and the northeastern edge of the Uinta Basin. The park straddles the border between the states of Colorado and Utah (Moffat and Uintah Counties). Elevation ranges from just under 5,000 ft at the southwest boundary to just over 9,000 ft at Zenobia Peak on the eastern boundary. Vegetation includes desert shrublands and riparian communities at the lowest elevations, semi- desert and montane shrub-steppe and pinyon-juniper woodlands at mid-elevations, and montane forest at the highest elevations. Pinyon-juniper woodlands comprise roughly 60% of Dinosaur’s vegetation; shrub-steppe covers approximately 25% of the landscape. A comprehensive vegetation classification and a vegetation map were completed for Dinosaur in 2008 and a soil survey was completed in 2007. Increasingly complex interactions between fire and invasive species have begun to present unprecedented complications for park managers, leading to the need for a comprehensive assessment of current landscape condition, analysis of historical patterns of change, and an improved understanding of the past and future role of fire in Dinosaur’s unique environment. -

Indigenous Architecture for Expeditionary Installations

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 3-16-2006 Indigenous Architecture for Expeditionary Installations Matthew B. Hutchings Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Hutchings, Matthew B., "Indigenous Architecture for Expeditionary Installations" (2006). Theses and Dissertations. 3383. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/3383 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE FOR EXPEDITIONARY INSTALLATIONS THESIS Matthew B. Hutchings, Major, USAF AFIT/GEM/ENV/06M-06 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED i The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense or U.S. Government. i AFIT/GEM/ENV/06M-06 INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE FOR EXPEDITIONARY INSTALLATIONS THESIS Presented to the Faculty Department of Systems and Engineering Management Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Engineering Management) Matthew B. Hutchings, BArch Major, USAF March 2006 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED ii AFIT/GEM/ENV/06M-06 INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE FOR EXPEDITIONARY INSTALLATIONS Matthew B. -

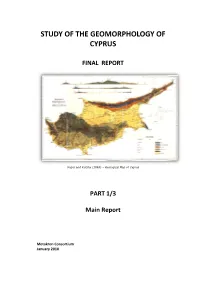

Study of the Geomorphology of Cyprus

STUDY OF THE GEOMORPHOLOGY OF CYPRUS FINAL REPORT Unger and Kotshy (1865) – Geological Map of Cyprus PART 1/3 Main Report Metakron Consortium January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1/3 1 Introduction 1.1 Present Investigation 1-1 1.2 Previous Investigations 1-1 1.3 Project Approach and Scope of Work 1-15 1.4 Methodology 1-16 2 Physiographic Setting 2.1 Regions and Provinces 2-1 2.2 Ammochostos Region (Am) 2-3 2.3 Karpasia Region (Ka) 2-3 2.4 Keryneia Region (Ky) 2-4 2.5 Mesaoria Region (Me) 2-4 2.6 Troodos Region (Tr) 2-5 2.7 Pafos Region (Pa) 2-5 2.8 Lemesos Region (Le) 2-6 2.9 Larnaca Region (La) 2-6 3 Geological Framework 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Terranes 3-2 3.3 Stratigraphy 3-2 4 Environmental Setting 4.1 Paleoclimate 4-1 4.2 Hydrology 4-11 4.3 Discharge 4-30 5 Geomorphic Processes and Landforms 5.1 Introduction 5-1 6 Quaternary Geological Map Units 6.1 Introduction 6-1 6.2 Anthropogenic Units 6-4 6.3 Marine Units 6-6 6.4 Eolian Units 6-10 6.5 Fluvial Units 6-11 6.6 Gravitational Units 6-14 6.7 Mixed Units 6-15 6.8 Paludal Units 6-16 6.9 Residual Units 6-18 7. Geochronology 7.1 Outcomes and Results 7-1 7.2 Sidereal Methods 7-3 7.3 Isotopic Methods 7-3 7.4 Radiogenic Methods – Luminescence Geochronology 7-17 7.5 Chemical and Biological Methods 7-88 7.6 Geomorphic Methods 7-88 7.7 Correlational Methods 7-95 8 Quaternary History 8-1 9 Geoarchaeology 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Survey of Major Archaeological Sites 9-6 9.3 Landscapes of Major Archaeological Sites 9-10 10 Geomorphosites: Recognition and Legal Framework for their Protection 10.1 -

Subdisciplines of Anthropology: a Modular Approach

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 260 774 JC 850 487 AUTHOR Kassebaum, Peter TITLE Subdisciplines of Anthropology: A Modular Approach. Cultural Anthropology. INSTITUTION College of Marin, Kentfield, Calif. PUB DATE ) [84] NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use- Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE ,MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Anthropology; Community Colleges; *Intellectual Disciplines; Learning Modules; TwoYear Colleges IDENTIFIERS *Cultural Anthropology ABSTRACT Designed for mse as supplementary instructional material in 4 cultural anthropologycourse; this learning module introduces the idea that anthropology iscomposed of a number of subdisciplines and that cultural amthropologyhas numerous subfields which are thg specialtyareas for many practicing anthropologists. Beginning with a general discussion ofthe field of anthropology, the paper next describes, defines, and discusses theoreticaland historical considerations, for the followingsubdisciplines within anthropology:. (1) archaeology; (2) physicalanthropology; (3) medical anthropology; (4) cultural anthropology; (5)ethnology; (6) =mathematical anthropology; (7),economicanthropology; (8) political anthropology; (9) the ethnography of law; (10)anthropology and education; (11) linguistics; (12) folklore; (13)ethnomusicology; (14) art and anthropology; (15) *nthropologyand belief systems; (16) culture and perionality; (17)-appliedanthropology; (18) urban anthropology; and,(1,9) economic anthropology.A test for students is included. (LAL) %N. ***************************************w******************************* -

Cultural Resources Overview Desert Peaks Complex of the Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks National Monument Doña Ana County, New Mexico

Cultural Resources Overview Desert Peaks Complex of the Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks National Monument Doña Ana County, New Mexico Myles R. Miller, Lawrence L. Loendorf, Tim Graves, Mark Sechrist, Mark Willis, and Margaret Berrier Report submitted to the Wilderness Society Sacred Sites Research, Inc. July 18, 2017 Public Version This version of the Cultural Resources overview is intended for public distribution. Sensitive information on site locations, including maps and geographic coordinates, has been removed in accordance with State and Federal antiquities regulations. Executive Summary Since the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966, at least 50 cultural resource surveys or reviews have been conducted within the boundaries of the Desert Peaks Complex. These surveys were conducted under Sections 106 and 110 of the NHPA. More recently, local avocational archaeologists and supporters of the Organ Monument-Desert Peaks National Monument have recorded several significant rock art sites along Broad and Valles canyons. A review of site records on file at the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division and consultations with regional archaeologists compiled information on over 160 prehistoric and historic archaeological sites in the Desert Peaks Complex. Hundreds of additional sites have yet to be discovered and recorded throughout the complex. The known sites represent over 13,000 years of prehistory and history, from the first New World hunters who gazed at the nighttime stars to modern astronomers who studied the same stars while peering through telescopes on Magdalena Peak. Prehistoric sites in the complex include ancient hunting and gathering sites, earth oven pits where agave and yucca were baked for food and fermented mescal, pithouse and pueblo villages occupied by early farmers of the Southwest, quarry sites where materials for stone tools were obtained, and caves and shrines used for rituals and ceremonies. -

Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Winter 2019 Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington Serafina erriF Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Education Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Ferri, Serafina, "Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington" (2019). All Master's Theses. 1124. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1124 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-GLACIAL FIRE HISTORY OF HORSETAIL FEN AND HUMAN-ENVIRONMENT INTERACTIONS IN THE TEANAWAY AREA OF THE EASTERN CASCADES, WASHINGTON __________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Resource Management ___________________________________ by Serafina Ann Ferri February 2019 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies