Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Architecture for Expeditionary Installations

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 3-16-2006 Indigenous Architecture for Expeditionary Installations Matthew B. Hutchings Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Hutchings, Matthew B., "Indigenous Architecture for Expeditionary Installations" (2006). Theses and Dissertations. 3383. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/3383 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE FOR EXPEDITIONARY INSTALLATIONS THESIS Matthew B. Hutchings, Major, USAF AFIT/GEM/ENV/06M-06 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED i The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense or U.S. Government. i AFIT/GEM/ENV/06M-06 INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE FOR EXPEDITIONARY INSTALLATIONS THESIS Presented to the Faculty Department of Systems and Engineering Management Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Engineering Management) Matthew B. Hutchings, BArch Major, USAF March 2006 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED ii AFIT/GEM/ENV/06M-06 INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE FOR EXPEDITIONARY INSTALLATIONS Matthew B. -

Animacy, Symbolism, and Feathers from Mantle's Cave, Colorado By

Animacy, Symbolism, and Feathers from Mantle's Cave, Colorado By Caitlin Ariel Sommer B.A., Connecticut College 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology 2013 This thesis entitled: Animacy, Symbolism, and Feathers from Mantle’s Cave, Colorado Written by Caitlin Ariel Sommer Has been approved for the Department of Anthropology Dr. Stephen H. Lekson Dr. Catherine M. Cameron Sheila Rae Goff, NAGPRA Liaison, History Colorado Date__________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Abstract Sommer, Caitlin Ariel, M.A. (Anthropology Department) Title: Animacy, Symbolism, and Feathers from Mantle’s Cave, Colorado Thesis directed by Dr. Stephen H. Lekson Rediscovered in the 1930s by the Mantle family, Mantle’s Cave contained excellently preserved feather bundles, a feather headdress, moccasins, a deer-scalp headdress, baskets, stone tools, and other perishable goods. From the start of excavations, Mantle’s Cave appeared to display influences from both Fremont and Ancestral Puebloan peoples, leading Burgh and Scoggin to determine that the cave was used by Fremont people displaying traits heavily influenced by Basketmaker peoples. Researchers have analyzed the baskets, cordage, and feather headdress in the hopes of obtaining both radiocarbon dates and clues as to which culture group used Mantle’s Cave. This thesis attempts to derive the cultural influence of the artifacts from Mantle’s Cave by analyzing the feathers. -

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

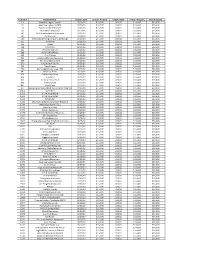

2021-02-09 Final Disbursement Spreadsheet

License # Establishment Check 1 Date Check 1 Amount Check 2 Date Check 2 Amount Total Awarded 51 American Legion Post #1 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 59 American Legion Post #28 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 74 Pancho's Villa Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 83 Asia GarDens/BranDy's 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 107 Bella Vista Pizzaria & Restaurant 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 140 The Blue Fox 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 200 Matanuska Brewing ComPany, Anchorage 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 217 Williwaw 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 225 Koots 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 258 Club Paris 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 321 Chili's Bar anD Grill 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 398 Buffalo WilD Wings 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 434 Fiori D'Italia 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 629 La Cabana Mexican Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 635 Serrano's Mexican Grill 11/12/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 670 Long Branch Saloon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 733 Twin Dragon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 750 Anchorage Moose LoDge 1534 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 761 MulDoon Pizza 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 814 The BraDley House 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 826 Tequila 61 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 842 The New Peanut Farm 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 888 Pizza OlymPia 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 891 Pizza Plaza 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 Anchorage977 Brewing ComPany (NeeD sPecial email if aPPlieD for Tier11/05/20 A) $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1064 Sorrento's 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1203 V.F.W. -

COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd

2558 Schillinger Rd. • 219-7761 COFFEE, SMOOTHIES, LUNCH & BEERS. CHUCK’S FISH ($$) 966 Government St.• 408-9001 LAID-BACK EATERY & FISH MARKET 3249 Dauphin St. • 479-2000 5460 Old Shell Rd. • 344-4575 SEAFOOD AND SUSHI BAMBOO 1477 Battleship Pkwy. • 621-8366 FOY SUPERFOODS ($) 551 Dauphin St.• 219-7051 STEAKHOUSE & SUSHI BAR ($$) RIVER SHACK ($-$$) 119 Dauphin St.• 307-8997 SERDA’S COFFEEHOUSE ($) TRADITIONAL JAPANESE WITH HIBACHI GRILLS SEAFOOD, BURGERS & STEAKS COFFEE, LUNCHES, LIVE MUSIC & GELATO CORNER 251 ($-$$) 650 Cody Rd. S • 300-8383 6120 Marina Dr. • Dog River • 443-7318 GULF COAST EXPLOREUM CAFE ($) 3 Royal St. S. • 415-3000 HIGH QUALITY FOOD & DRINKS BANGKOK THAI ($-$$) THE GRAND MARINER ($-$$) HOMEMADE SOUPS & SANDWICHES 1539 US-98 • Daphne • 517-3963 251 Government St • 432-8000 DELICIOUS, TRADITIONAL THAI CUISINE 65 Government St. • 208-6815 28600 US 98 • Daphne • 626-5286 LOCAL SEAFOOD & PRODUCE DAUPHIN’S ($$-$$$) 6036 Rock Point Rd. • 443-7540 $10/PERSON • $$ 10-25/PERSON • $$$ OVER 25/PERSON SHELL FOOD MART ($) 3821 Airport Blvd. • 344-9995 HOOTERS ($) Co. Rd. 49 & U.S. 98• Magnolia Springs HIGH QUALITY FOOD WITH A VIEW 3869 Airport Blvd. • 345-9544 107 St. Francis St/RSA Building • 444-0200 BANZAI JAPANESE THE HARBOR ROOM ($-$$) COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd. • 661-9117 SIMPLY SWEET ($) RESTAURANT ($$) UNIQUE SEAFOOD 28975 US 98 • Daphne • 625-3910 CUPCAKE BOUTIQUE DUMBWAITER ($$-$$$) TRADITIONAL SUSHI & LUNCH. 64 S. Water St. • 438-4000 9 Du Rhu Dr. Suite 201 ALL SPORTS BAR & GRILL ($) 6207 Cottage Hill Rd. Suite B • 665-3003 312 Schillinger Rd./Ambassador Plaza• 633-9077 3408 Pleasant Valley Rd. • 345-9338 JAMAICAN VIBE ($) 167 Dauphin St. -

Beaches & Holiday Homes Dog-Friendly Directory

South Devon LOVES DOGS A pet-friendly holiday guide from Coast & Country Cottages Alfie Bear visits Salcombe TipsHoliday from advice local from vets, experts bloggers and The National Farmers’ Union The best forBeaches you and your & four-leggedholiday homes friend Dog-friendlyOver 100 eateries, attractionsdirectory and useful contacts SOUTH DEVON LOVES DOGS Welcome I’m Alfie, an English Springer Spaniel… Water obsessed and beach mad! I am always on the road with my human, sniffing out the very best in all things dog-friendly. Being a famous blogger allows me and my best friend Emma to travel around the country, going to prestigious events such as Crufts and staying in luxury properties like Poll Cottage in the heart of Salcombe. Together, Emma and I find our favourite dog-friendly locations, that our followers love to read about. Emma Bearman is a freelance Personally, I love Devon; it is the perfect place for a doggy photographer based in the holiday. With so many beaches to explore, I know I will Warwickshire countryside. have the best adventures. We always have to take a trip to Emma’s photographs of her beloved canine pal ‘Alfie Bear’, East Portlemouth, with miles of sandy beach and endless quickly turned into a full-time swimming. I love stopping at our favourite pub, The Victoria job and fully functioning online Inn, for a bite to eat on the way home. blog with thousands of fans visiting www.alfiebear.com. Alfie Bear Star of dog blog alfiebear.com We know how lucky we are to live and work in this Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty -

Architectural Co-Design for Indigenous Housing WHAT CAN WE LEARN from CASE STUDIES? Presentation by Louise Atkins CHRA Co

Architectural Co-design for Indigenous Housing WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM CASE STUDIES? Presentation by Louise Atkins CHRA Congress, April 4, 2019 Presentation Outline • Purpose • Context • Collaborative Architectural Co-Design – definition • Case Studies and Best Practices • Key Learnings for Indigenous Housing • Contact Info & Document Links Purpose •How collaborative architectural co-design principles and processes lead to excellence and best practices applicable to Indigenous housing •Themes •Case Study Examples Housing Matters/Architecture Matters • Housing is fundamental to wellbeing of families and individuals • For Indigenous housing, architectural design matters: • Meets physical needs, household composition • Fosters a sense of belonging, contributes to healing • Reflects Indigenous identity and is a base for cultural expression, reclamation and growth Context • 2016-17 Indigenous Task Force established by Royal Architectural Institute of Canada • ITF membership includes Indigenous and non- Indigenous architects and designers who are working in Indigenous contexts • Fosters and promotes Indigenous design in Canada. Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Indigenous Task Force International Indigenous Architectural and Design Symposium • May 27, 2017 • Gathered speakers and 160 delegates from across Canada, New Zealand, Australia and the United States. • The first ever event privileging Indigenous architecture and design in Canada and across the globe. “The first ever event privileging Indigenous architecture and design in Canada” -

A Study of Vernacular Architecture and Indigenous Construction Techniques of the Kullu Region, Himachal Pradesh

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 A study of vernacular architecture and indigenous construction techniques of the Kullu Region, Himachal Pradesh Manoj Panwar#1, Sandeep Sharma2 1 D. C. R. University of Science & Technology, Murthal, India 131001 2 National Institute of Technology Hamirpur, Hamirpur, India 177005 Abstract: The architecture of a place depends on the climate, geography, resource availability, material and knowledge of construction techniques, geography, building rules and regulations, socio-economic conditions, household characteristics, culture, infrastructure availability, and other natural forces. The hilly regions remain less connected to outside regions, both in physical and information linkages. The exchange of materials and information about the construction techniques has endangered the usage of indigenous material and construction techniques for the development of climate-responsive architecture. The authors thoroughly investigated the local materials and contemporary construction techniques of the Kullu region, Himachal Pradesh. Vernacular buildings constructed by using indigenous materials and construction techniques are more responsive to their geo-climatic conditions. The lessons of traditional wisdom in building construction can be a very powerful tool for sustainable development. The paper concludes with the plausible policy required for the preservation of indigenous construction techniques for sustainable development. Keywords: Vernacular Architecture; Indigenous Construction Techniques; Hilly Region; Sustainable Development. Note: This paper is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled ‘study of vernacular architecture and indigenous construction techniques of the Kullu Region, Himachal Pradesh’ presented at International Conference on Advances in Construction Materials and Structures (ACMS-2018) organised by Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, Roorkee, Uttarakhand, India [March 7-8, 2018]. -

Jack Clemo 1916-55: the Rise and Fall of the 'Clay Phoenix'

1 Jack Clemo 1916-55: The Rise and Fall of the ‘Clay Phoenix’ Submitted by Luke Thompson to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English In September 2015 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract Jack Clemo was a poet, novelist, autobiographer, short story writer and Christian witness, whose life spanned much of the twentieth century (1916- 1994). He composed some of the most extraordinary landscape poetry of the twentieth century, much of it set in his native China Clay mining region around St Austell in Cornwall, where he lived for the majority of his life. Clemo’s upbringing was one of privation and poverty and he was famously deaf and blind for much of his adult life. In spite of Clemo’s popularity as a poet, there has been very little written about him, and his confessional self-interpretation in his autobiographical works has remained unchallenged. This thesis looks at Clemo’s life and writing until the mid-1950s, holding the vast, newly available and (to date) unstudied archive of manuscripts up against the published material and exploring the contrary narratives of progressive disease and literary development and success. -

Wood Design & Building – Winter 2019/20

Six dollars Winter 2019-20 — Number 84 CHAMPIONS OF WOOD #40063877 Publications Mail agreement The Modular 2019 Wood Innovators & Unit (MU50) Design Awards Gamechangers An elegantly sustainable award-winner A full spectrum of excellence Architects who master wood FIRST. AGAIN. UL Design No. V314, the first ASTM E119 (UL 263) fire-retardant-treated lumber and plywood 2-Hour bearing wall assembly. UL System No. EWS0045, the first NFPA 285 fire-retardant-treated lumber and plywood exterior wall system demonstrating compliance with IBC Section 1402.5. Based on UL Design No. V314, UL System No. Leading the way. Learn more at frtw.com EWS0045 requires UL Classified Pyro-Guard® For technical assistance: 1-800-TEC-WOOD fire-retardant-treated lumber and plywood. contents Above and on the cover: The Modular Unit (MU50) PHOTOS: ALTKAT Architectural Photography O C F The Modular Unit (MU50) 26 CHAMPIONS OF WOOD A project on oceanside cliffs in Turkey wins a 2019 Wood Design 2019 Wood Design & Building Award Winners 12 & Building Award (Honor). Wood Design & Building recognizes excellence, innovation and creativity in a wide range of wood projects D Cardinal House 30 Against the Grain 6 Douglas Cardinal presents a modular, mass Artful staircases timber solution to address the housing crisis Wood Chips 8 Innovators & Gamechangers 34 Ten architects who are wood champions, Projects to watch and recent news including some of their best projects Wood Ware 46 Foon Skis uses local B.C. wood for handcrafted custom skis Ideas & Applications 42 Sansin answers some of the most common questions about architectural finishes for wood Buildings that inspire us This was my second year observing the Wood Design & Building Award jury deliberations, and it was an event I eagerly anticipated for months. -

Inalienable Interiors : Consumerism and Anthropology, 1890 to 1920

INALIENABLE INTERIORS: CONSUMERISM AND ANTHROPOLOGY, 1890 TO 1920 By Aaron Wayne McCullough A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of American Studies—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT INALIENABLE INTERIORS: CONSUMERISM AND ANTHROPOLOGY, 1890 TO 1920 By Aaron Wayne McCullough In this dissertation, I examine how and why anthropology became a significant discourse through which consumers, taste makers, and authors attempted to understand and navigate the consumer marketplace of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century United States. Anthropology, in its focus on “primitive” material cultures, perceived primitive objects as unconscious and unchanging expressions of identities defined by culture, race, or natural physiography. In a marketplace of alienable commodities, of objects circulating not only from producer to consumer, but also within and across the boundaries of identities, anthropology allowed consumers a discourse through which they could understand the objects of others; and through which they could imagine, identify, or idealize objects that expressed their own racial, national, class, or cultural identity. I call the consumer that emerged from this discourse of consumption, borrowing from historian James Clifford, an ethnographic consumer: an anthropologically aware, rational, consumer self, capable of navigating a cosmopolitan marketplace by perceiving and idealizing objects as cultural. I trace this figure, a version of Walter Benjamin’s flâneur, -

Raic International Indigenous Architecture and Design Symposium

JUNE 23–24, 2021 RAIC INTERNATIONAL INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN SYMPOSIUM The RAIC International Indigenous Architecture and Design Symposium is hosted by the RAIC Indigenous Task Force. The Symposium focuses on Indigenous representation, narratives, and collaborations. The two streams for the 2021 Symposium are: ` Making Room for New Indigenous Voices on the Leading Edge of Architecture Practice ` Collaborations: Indigenous / Non-Indigenous Co-Design and Building with First Nations, Metis and Inuit Communities DAILY SCHEDULES (All times in Eastern Standard) DAY 1 - JUNE 23, 2021 11:00 AM – 11:15 AM Welcome and Introductions 11:15 AM – 12:15 PM Session 1A 12:15 PM – 12:30 PM Break 12:30 PM – 1:30 PM Session 1B 1:30 PM – 2:00 PM Lunch 2:00 PM – 3:00 PM Session 1C 3:00 PM – 3:15 PM Break 3:15 PM – 4:15 PM Session 1D 4:15 PM – 4:30 PM Closing Remarks DAY 2 - JUNE 24, 2021 11:00 AM – 11:15 AM Welcome and Introductions 11:15 AM – 12:15 PM Session 2A 12:15 PM – 12:30 PM Break 12:30 PM – 1:30 PM Session 2B 1:30 PM – 2:00 PM Lunch 2:00 PM – 3:00 PM Session 2C 3:00 PM – 3:15 PM Break 3:15 PM – 4:15 PM Session 2D 4:15 PM – 4:30 PM Closing Remarks RAIC INTERNATIONAL INDIGENOUS 1 RAIC 2021 VIRTUAL CONFERENCE ON ARCHITECTURE ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN SYMPOSIUM SESSIONS – DAY 1 - JUNE 23, 2021 1A INDIGENOUS PLACEKEEPING PEDAGOGY 7-4-4-7: RE-IMAGINING ARCHITECTURE Making Room for New Indigenous Voices on the Leading Edge of Architecture Practice Recent research shows that the “post-Millennial generation is already the most racially and ethnically diverse generation” in history (Frye + Parker, 2020).