Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malins, Stephen.Pdf (1.094Mb)

CONVERGENCE AND COLLABORATION: INTEGRATING CULTURAL AND NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT By STEPHEN JOHN MALINS B.A., University of Victoria, 1990 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ______________________________ Dr. Alice MacGillivray, Thesis Supervisor Fielding Graduate University ______________________________ ______________________________ Thesis Coordinator Michael-Anne Noble, Director School of Environment and Sustainability School of Environment and Sustainability ROYAL ROADS UNIVERSITY March 2011 © Stephen John Malins, 2011 Convergence and Collaboration ii ABSTRACT Protected heritage area management is challenged by conflicting priorities perpetuated by the real and perceived dichotomy between cultural and natural resource management, their practitioners, their disciplines, and their values. Current guidelines promote integrating cultural and natural resource management to ensure holistic management of all values within a protected heritage area. This paper uses the management of the Cave and Basin National Historic Site to illustrate challenges in protecting both historic and natural resources. A qualitative inductive study included analysis of interview and focus group data for the site and similar protected heritage areas. The gap between integrative policies and the tendency for uni-disciplinary approaches to the practice of managing protected heritage areas is investigated. Five barriers to integration, such as lack of awareness, and five methods for progress, including facilitated inclusion, are examined. The author proposes collaborative, sustainable, values-based practices for the successful integration of cultural and natural resource management. Convergence and Collaboration iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to a number of people who have seen me through this journey from tilting at windmills to slaying of dragons. -

Pdf Blue Gum Forest

Mt Wilson Mt Irvine Bushwalking Group Volume 24 Issue 4 April 2014 BLUE GUM FOREST – PERRYS TO GOVETTS TOPIC the magical aura which exists OUR MARCH among those majestic Blue Gums. WALK (The full Herald article is BLUE GUM FOREST – reproduced in Andy PERRYS LOOKDOWN to Macqueen’s marvellous book GOVETTS LEAP LOOKOUT Back from the Brink - Blue Friday 21 st March 2014 Gum Forest and the Grose th Wilderness , an absolute ‘must On Saturday 24 October read’ for anyone interested in 1931the Sydney Morning Herald carried a story titled The Blue the history and preservation of Gum Forest – Plea for its this area.) Protection , it read in part: “In the Today’s planned venue heart of the Grose Valley, in the attracted a good roll up with shadow of Mt King George, Autumn in the Bush twenty-three gathering at where Govett’s Leap Creek joins Govetts Leap Lookout. We the Grose, there is a wondrous watched the morning sun forest of tall trees, cathedral-like in its burning through the light haze to illuminate splendour. Mountain mists rise from it in early the surrounding cliffs and glanced, perhaps morning, later a blue haze invests its noble askance, at the bottom of Govetts Leap Falls aisles, and in the evening, when the setting sun from which we will climb later in the day. Our is reflected from an overtowering cliff-face, primary goal for the day was hidden behind sunbeams filter through the trees in shafts of the ridge running down from the base of Pulpit dancing gold.” Rock. -

Submission As an Attachment Via Email E

To the Department of Industry Submission regarding the Proposal to grant a commercial lease for Katoomba Airfield Submitted by Manda Kaye CO-FOUNDER BLUEMTNSPEACEKEEPERS, SMALL BUSINESS OWNER AND MTNS MADE CREATIVE [email protected] / bluemtnspeacekeepers.org July 26, 2019 Mr Glen Bunny Department of Industry, Crown Lands [email protected] Dear Mr Bunny RE: LX 602686 – submission as an objection to proposed lease of Katoomba Airfield I am a small business owner, a member of the growing Mtns Made creative community and one of the co-founders of Blue Mtns Peacekeepers. I’m writing to you to express my deep concern over the proposal to commercially develop Katoomba Airfield, which, if it is granted, will profit the leaseholder at an enormous cost to our local community, environment and economy. Who are Blue Mtns Peacekeepers and what is our position? Blue Mtns Peacekeepers was begun by a group of local citizens who are deeply concerned about the proposed commercial lease of Katoomba Airfield. We speak for the vulnerable plant and animal species in this glorious and fragile World Heritage Area where we live. We represent the many residents and visitors who come here to experience the natural quiet of the bush. It is the mission of the Blue Mtns Peacekeepers to protect the tranquil environment that supports the biodiversity of our beloved Blue Mountains National Park - for its own sake, but also, because this is the bedrock of our local economy. We object to the approval of any commercial lease on the crown land containing Katoomba Airfield. To protect the ecology and the economy that depends on it, this crown land should be added to the Blue Mountains National Park and World Heritage Area by which it is surrounded. -

Derwent Estuary Program Environmental Management Plan February 2009

Engineering procedures for Southern Tasmania Engineering procedures foprocedures for Southern Tasmania Engineering procedures for Southern Tasmania Derwent Estuary Program Environmental Management Plan February 2009 Working together, making a difference The Derwent Estuary Program (DEP) is a regional partnership between local governments, the Tasmanian state government, commercial and industrial enterprises, and community-based groups to restore and promote our estuary. The DEP was established in 1999 and has been nationally recognised for excellence in coordinating initiatives to reduce water pollution, conserve habitats and species, monitor river health and promote greater use and enjoyment of the foreshore. Our major sponsors include: Brighton, Clarence, Derwent Valley, Glenorchy, Hobart and Kingborough councils, the Tasmanian State Government, Hobart Water, Tasmanian Ports Corporation, Norske Skog Boyer and Nyrstar Hobart Smelter. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Derwent: Values, Challenges and Management The Derwent estuary lies at the heart of the Hobart metropolitan area and is an asset of great natural beauty and diversity. It is an integral part of Tasmania’s cultural, economic and natural heritage. The estuary is an important and productive ecosystem and was once a major breeding ground for the southern right whale. Areas of wetlands, underwater grasses, tidal flats and rocky reefs support a wide range of species, including black swans, wading birds, penguins, dolphins, platypus and seadragons, as well as the endangered spotted handfish. Nearly 200,000 people – 40% of Tasmania’s population – live around the estuary’s margins. The Derwent is widely used for recreation, boating, fishing and marine transportation, and is internationally known as the finish-line for the Sydney–Hobart Yacht Race. -

Volunteer Fire Fighters Association

the Winter 2012 volunteer fire fighter Volume 4 No.1 Official magazine of the Volunteer Fire Fighters Association Volunteer Rural Fire-Fighters Could Face Prosecution Under New National Safety Laws National Corridors Plan Concern Estimating Wind Speed Encouraging our Volunteers NEW WEBSITE www.volunteerfirefighters.org.au inside front cover Contents Volunteer Fire Fighters Executive-Council and From the President’s Desk 2 Representatives THE VOLUNTEER FIRE FIGHTERS ASSOCIATION 2011/12 Who we are: 4 Senior Management Team 5 Independent Hazard Reduction Audit Panel 5 Executive Council Letters to the Editor 6 Peter Cannon, President – Region West Brian Williams, Vice President – Region East VFFA Profile – Denis McIntyre 10 Val Cannon, Secretary – Region West – Alan Brown 11 Michael Scholz, Treasurer – Region East Estimating Wind Speed 12 Jon Russell, Media/Website Officer – Region East Andrew Scholz, Media /Website – Region East National Corridors Plan Concern 14 Laurie Norton – Region South The NAPA Pilot Proposal 16 Peter Cathles – Region South Alan Brown – Region South Volunteer Rural Fire-Fighters Could Face Prosecution Rod Young – Region North Under New National Safety Laws 19 Tony Ellis – Region West RFS Library 25 Don Tarlinton – Region South Neil Crawley – Region South AA Safety & Workwear 26 Challenge Testing – Recognised Prior Learning 28 Patrons BAL Compliance, ‘to seal or not to seal’ that’s the question 29 Mr. Kurt Lance. Encouraging our Volunteers 30 Fire Tragedy in the Blue Mountains 31 Consultants NSW Farmers and Bushfire Matters 35 Mr. Phil Cheney, Retired Fire Scientist CSRIO Photo Gallery 36 Mr. Arthur Owens, Retired RFS FCO Mr. Kevin Browne, AFSM The Good Ol’ Days 37 The Gravy Train 38 Regional Representatives Vale – Dennis Joiner 39 for the VFFA VFFA Membership Application 40 REGION SOUTH: REGION NORTH: Ron McPherson Doug Wild Peter Webb Steve McCoy John Ross Fergus Walker The VFFA welcomes and encourages members to send Max Hedges in any pictures, photos and articles of interest. -

Great Ocean Road and Scenic Environs National Heritage List

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Item: 1 Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Great Ocean Road and Rural Environs Other Names: Place ID: 105875 File No: 2/01/140/0020 Primary Nominator: 2211 Geelong Environment Council Inc. Nomination Date: 11/09/2005 Principal Group: Monuments and Memorials Status Legal Status: 14/09/2005 - Nominated place Admin Status: 22/08/2007 - Included in FPAL - under assessment by AHC Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Apollo Bay Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): 42000 Address: Great Ocean Rd, Apollo Bay, VIC, 3221 LGA: Surf Coast Shire VIC Colac - Otway Shire VIC Corangamite Shire VIC Location/Boundaries: About 10,040ha, between Torquay and Allansford, comprising the following: 1. The Great Ocean Road extending from its intersection with the Princes Highway in the west to its intersection with Spring Creek at Torquay. The area comprises all that part of Great Ocean Road classified as Road Zone Category 1. 2. Bells Boulevarde from its intersection with Great Ocean Road in the north to its intersection with Bones Road in the south, then easterly via Bones Road to its intersection with Bells Beach Road. The area comprises the whole of the road reserves. 3. Bells Beach Surfing Recreation Reserve, comprising the whole of the area entered in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) No H2032. 4. Jarosite Road from its intersection with Great Ocean Road in the west to its intersection with Bells Beach Road in the east. -

Land of Tasmania Report by the Surveyor-General

(No. 18.) 18 6 4. TASMAN I A. LANDS OF TASMANIA. REPORT BY THE SURVEYOR-GENERAL. Laid upon the Table by Mr. Colonial Treasurer, and ordered by the House to he printed, 29 June, I 864. LANDS OF TASTh1ANIA; . COMPILED FROM THE OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE SURVEY DEPARTMENT, DY ORDER OF THE HONORABLE THE COLONIAL TREASURER. Made up to the 31st December, 1862. '««f,man ta: JAMES BARNARD, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, HOBART TOWN. 186 4. T A B L E OF C O N T E N T S. PAGE PREFACE •••••••••• , • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 Area of Tasmania, with alienated and unalienated Lands . • . • • • • . • . 17 Population of Tasmania ...............••..• ,........................... ib. Ditto of Towns . • • . • • • . • . • . • . • • . • . ] 8 Country Lands granted and sold since 1804 ..• , • • • • . • • • • • . • • • . • . • • • • • . 19 Town· Lands sold . • • • • • . • . • . • • • • • . • • • . • . • • • . • . • . 20 'fown Lands sold for Cash under " The Waste Lands Act" ·• . • • • • • • • • • • . • . 21 Deposits forfeited- on ditto •.••• , . • . • • • . • • . • • • . • . • . .. • . • . • • . • 40 Town Lands sold on Credit . • • • . • . • • • • . • • . • • • • . • . • . • . • • • • 42 Agricultural Lands sold for Cash, under 18th Sect. of" The Waste Lands Act". 45 Ditto on Credit, ditto .•.•• , • . • • • • . • . • . • . • • • • • . • . • • • . • • • • . • . 46 Ditto for Cash, under 19th Sect. of" The Waste Lands Act" • . • . 49 Ditto on Credit, ditto . • . • • • • • • • • • . • . • . • . • . • • • • • -

LATE WISCONSIN GLACIATION of TASMANIA by Eric A

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 130(2), 1996 33 LATE WISCONSIN GLACIATION OF TASMANIA by Eric A. Calhoun, David Hannan and Kevin Kiernan (with two tables, four text-figures and one plate) COLHOUN, E.A., HANNAN, D. & KIERNAN, K., 1996 (xi): Late Wisconsin glaciation of Tasmania. In Banks, M. R. & Brown, M.F. (Eds): CLIMATIC SUCCESSION AND GLACIAL HISTORY OF THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE OVER THE LAST FIVE MILLION YEARS. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 130(2): 33-45. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.130.2.33 ISSN 0080-4703. Department of Geography, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia 2308 (EAC); Department of Physical Sciences, University of Tasmania at Launceston, Tasmania, Australia 7250 (DH); Forest Practices Board ofTasmania, 30 Patrick Street, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7000 (KK). During the Late Wisconsin, icecap and outlet glacier systems developed on the West Coast Range and on the Central Plateau ofTasmania. Local cirque and valley glaciers occurred in many other mountain areas of southwestern Tasmania. Criteria are outlined that enable Late Wisconsin and older glacial landforms and deposits to be distinguished. Radiocarbon dates show Late Wisconsin ice developed after 26-25 ka BP, attained its maximum extent c. 19 ka BP, and disappeared from the highest cirques before 10 ka BP. Important Late Wisconsin age glacial landforms and deposits of the West Coast Range, north-central and south-central Tasmania are described. Late Wisconsin ice was less extensive than ice formed during middle and earlier Pleistocene glaciations. Late Wisconsin snowline altitudes, glaciological conditions and palaeodimatic conditions are outlined. Key Words: glaciation, Tasmania, Late Wisconsin, snowline altitude, palaeoclimate. -

Voices of Aboriginal Tasmania Ningina Tunapri Education

voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry education guide Written by Andy Baird © Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery 2008 voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry A guide for students and teachers visiting curricula guide ningenneh tunapry, the Tasmanian Aboriginal A separate document outlining the curricula links for exhibition at the Tasmanian Museum and the ningenneh tunapry exhibition and this guide is Art Gallery available online at www.tmag.tas.gov.au/education/ Suitable for middle and secondary school resources Years 5 to 10, (students aged 10–17) suggested focus areas across the The guide is ideal for teachers and students of History and Society, Science, English and the Arts, curricula: and encompasses many areas of the National Primary Statements of Learning for Civics and Citizenship, as well as the Tasmanian Curriculum. Oral Stories: past and present (Creation stories, contemporary poetry, music) Traditional Life Continuing Culture: necklace making, basket weaving, mutton-birding Secondary Historical perspectives Repatriation of Aboriginal remains Recognition: Stolen Generation stories: the apology, land rights Art: contemporary and traditional Indigenous land management Activities in this guide that can be done at school or as research are indicated as *classroom Activites based within the TMAG are indicated as *museum Above: Brendon ‘Buck’ Brown on the bark canoe 1 voices of aboriginal tasmania contents This guide, and the new ningenneh tunapry exhibition in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, looks at the following -

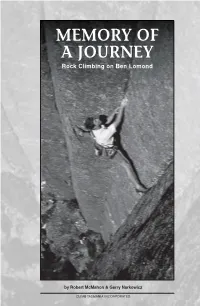

MEMORY of a JOURNEY Rock Climbing on Ben Lomond

MEMORY OF A JOURNEY Rock Climbing on Ben Lomond by Robert McMahon & Gerry Narkowicz CLIMB TASMANIA INCORPORATED To all those who enjoyed the freedom of the mountain and took part in the great adventure. “Think where man’s glory most begins and ends, And say my glory was I had such friends.” WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS BEN LOMOND First published in 2008 by Climb Tasmania Incorporated, in association with Oriel, 150 Frankford Road Exeter, Tasmania 7275. Copies of this book are available from the above address or by phoning (03) 63944225. Email : [email protected] Copyright © 2008 by Robert McMahon and Gerry Narkowicz of Climb Tasmania Incorporated. ISBN : 0 9578179 8 3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a Photography by Robert McMahon unless otherwise indicated retrieval system, or transmitted by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or Front Cover: Denison Crag at dawn. otherwise) without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized Frontispiece: Brent Oldinger on C.E.W Bean (23) at Ragged Jack. act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. Back Cover Inset: Gerry Narkowicz on the marathon second pitch of Howitzer (22) at Pavement Bluff. CONTENTS Numbers in brackets are route numbers Access Map 6 LOCAL LOSER 45 RAGGED JACK 97 Rhine Buttress (292-297) 152 Overview Map 7 Introduction and Access 47 Map To Ragged Jack 98 Trinity Face (298-302) 155 Introduction 8 Local -

Controversies Over the Name of Mount Kosciuszko

Controversies over the name of Mount Kosciuszko Andrzej Kozek 2020-03-26 The story we are going to tell is about visibility of the highest peak of the continental Australia, Mt Kosciuszko (2228 m), from all directions around because this is the key to understanding where all the troubles with naming of the mountain came from. The tourism industry is another factor. Tourism Industry in Australia became an important component of Australian economy. In the year to June 2019, there were over 8.5 million international visitors in Australia, an increase of 3% from 2018. Tourism contributed 8.0% of Australia's total export earnings in 2010-11. Australian Alps with the highest Australian continental peak, Mt Kosciuszko belong to the icons attracting tourists [1,2]. Often over 1000 tourists visit Mt Kosciuszko on summer weekend days. Clearly the walk from Thredbo is the most popular one. Chair lifting over 560 m to level 1930 m [3], then a comfortable walk 5 km over elevated steel mesh way to Rawson Pass (2124 m) with ecological toilets brings you to the final 1.5 km on a maintained road to the top of Australia. The metal walkways have been built in the 1980’s. What a cute description of the walk has been found on the internet. Climbing Mount Kosciuszko is worth doing. It is pleasant. It is easy. It is hugely enjoyable. And, when you have done it, you can bask in the glory that once you stood on the highest point between the Andes and the East African Plateau. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS 01' THII ROYAL SOCIETY 01' TASMANIA, JOB (ISSUED JUNE, 1894.) TASMANIA: PJUl'TBD .&.T «TO XBROUBY" OJ'lPIOE, JUOQUUIE BT., HOBART. 1894. Googk A CATALOGUE OF THE MINERALS KNOWN TO OCCUR IN TASMANIA, WITH NOTES ON THEIR DISTRIBUTION• .Bv W. F. PETTERD. THE following Catalogue of the Minerals known to occur and reeortled from this Island is mainly prepared from specimen~ contained in my own collection, and in the majority of instances I have verified the identifications by careful qualitative analysis. It cannot claim any originality of research, 01' even accluac)" of detail, but as the material has been so rapidly accumulating during the past few )'ears I bave thoug-ht it well to place on record the result of my personal observation and collecting, wbich, with information ~Ieaned from authentic sources, may, I trust, at least pave tbe way for a more elaborate compilation by a more capable authority. I have purposely curtailed my remarks on the various species 80 Rs to make them as concise as possible, and to redulle the bulk of the matter. As an amateur I think I may fairly claim tbe indulgence of the professional or otber critics, for I feel sure tbat my task has been very inadequately performed in pro portion to the importance of the subjeot-one not only fraugbt with a deep scientific interest on account of tbe multitude of questions arisin~ from the occurrence and deposition of the minerals them selves, but also from the great economic results of our growing mining indu.try. My object has been more to give some inform ation on tbis subject to the general student of nature,-to point out tbe larg-e and varied field of observation open to him,- than to instruct the more advanced mineralo~ist.