Malins, Stephen.Pdf (1.094Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISC A3 2016 Canada Alaska Sue Verrall E-Version

CANADA & ALASKA Lakes Wildlife Glaciers Mountains Wilderness Salmon Fishing Join me as we explore the spectacular scenery and Canadian Rockies wildlife of the Canadian Rockies and Alaska’s Inside Passage & Wild Alaska. - Tour Escort, Sue Verrall with Sue Verrall Sue Verrall is a landscape and rural development specialist, now based back in Canterbury after many years 26 day Escorted Tour, 6-31 July, 2016 living in Africa. Sue regularly escorts tours to Tanzania, Ethiopia and India where she draws on her regional knowledge and many friendships to Experience all the Your tour highlights: create a rare experience of people highlights of the l Rocky Mountaineer Train and fun times when travelling. Canadian Journey – Vancouver to We are delighted to be able to offer Rockies and the Jasper this one-off tour to Canada & Alaska Inside Passage l Jasper, Lake Louise and for 2016. Like Africa and India, this Banff tour has been crafted to include all on this small the key highlights, sights and l group journey. Drive the Icefield Parkway experiences as well as some off the From the and visit the Athabasca beaten track activities. The tour is Glacier limited to just 20 and typically Sue’s cosmopolitan city trips are sell-outs, mostly to friends l The Calgary Stampede – of Vancouver you will and family of past travellers. Rodeo Event & Grandstand enjoy the stunning Rocky Show Meet your fellow travellers Mountaineer train journey to Jasper. Marvel at the l Vancouver – Stanley Park, We will have social evenings before magnificent Rockies as we travel from Jasper to Lake Capilano Bridge & Grouse the tour where you can meet Sue and Louise and Banff. -

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

The Heritage Character of the Honeymoon Cabin Resides in Its Picturesque Mountainous Setting and in Its Rustic Design. Its Simp

HERITAGE CHARACTER STATEMENT Honeymoon Cabin Skoki Ski Lodge National Historic Site Banff National Park, Alberta The Honeymoon Cabin of the Skoki Ski Lodge National Historic Site was constructed in 1932. Constructed during the management tenure of Peter and Catherine Whyte, it was one of two structures built to provide additional accommodation shortly after construction of the main building. The cabin currently retains its original use as tourist accommodation. Parks Canada is the custodian of this National Historic Site. See FHBRO Building Report 96-1 05. Reasons for Designation The Honeymoon Cabin of the Skoki Ski Lodge National Historic Site has been designated Classified primarily for its environmental significance, but also for its architectural qualities and historical associations. The Skoki Ski Lodge is environmentally significant for several reasons. Situated twelve miles north of Lake Louise in the Skoki Valley, the resort lies in the centre of magnificent ski touring country close to several glaciers. The Honeymoon Cabin and four other guest cabins are arranged in a fan-like semi-circle around the centrally- placed main building. Since access to the site has not changed, being restricted to foot, horseback and ski trail, the remote, wilderness character remains unspoiled. The Skoki Ski Lodge is a unique example of an original rustic winter resort characteristic of the Banff region. It has remained virtually unchanged since its completion in 1936. The historical significance of the Honeymoon Cabin, as a component of the entire lodge, derives from its association with the growth of back-country recreation in the national parks and the development of tourism. -

Archaeological Assessment of the Twin Falls Teahouse National Historic Site, Yoho National Park

Archaeological Assessment of the Twin Falls Teahouse National Historic Site, Yoho National Park William Perry Cultural Resource Services, Parks Canada, Calgary May 1999 Twin Falls Teahouse National Historic Site Assessment 2 Introduction From September 8th to the 10th, 1998, the Twin Falls Tea House National Historic Site located in the backcountry of Yoho National Park (figure 1), was assessed by an archaeological team from Cultural Resource Services, Western Canada Service Centre, Parks Canada, Calgary. The assessment was part of a larger heritage recording and assessment program led by Public Works, Architecture and Engineering, Calgary. The archaeological component of this recording involved the excavation at three locations along the foundation of the log structure to aid the restoration recording team in obtaining structural information as well as enhancing the site's historic and archaeological information base. Background The site was initially recorded in 1985 (Sumpter and Perry 1987:31), where the log chalet was photographed and a brief structural history was reported (See Getty 1972:200; Canadian Pacific Railway 1928:2,8,9; and Richard Friesen and Associates 1985:npag.). This initial assessment was a baseline recording and did not provide any management direction. Rectangular in shape, the lodge was constructed in three stages. The first stage involved the erection of a one-room cabin ca. 1908. The second stage, an addition, was constructed about 1917. The third stage, a two-storey log chalet addition, was constructed around 1923-24 (Getty 1972:200). This log structure was the first of five teahouses to be erected by the Canadian Pacific Railway in Yoho National Park. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’S 2016 Media Kit

Assignment: Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’s 2016 Media Kit TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 4 WHERE IN THE WORLD IS VANCOUVER? ........................................................ 4 VANCOUVER’S TIMELINE.................................................................................... 4 POLITICALLY SPEAKING .................................................................................... 8 GREEN VANCOUVER ........................................................................................... 9 HONOURING VANCOUVER ............................................................................... 11 VANCOUVER: WHO’S COMING? ...................................................................... 12 GETTING HERE ................................................................................................... 13 GETTING AROUND ............................................................................................. 16 STAY VANCOUVER ............................................................................................ 21 ACCESSIBLE VANCOUVER .............................................................................. 21 DIVERSE VANCOUVER ...................................................................................... 22 WHERE TO GO ............................................................................................................... 28 VANCOUVER NEIGHBOURHOOD STORIES ................................................... -

Canada's 46 National Parks, 168 National Historic Sites, 4 National

Canada’s 46 National Parks, 168 National Historic Sites, 219 Les 46 parcs nationaux, 168 lieux historiques nationaux, 4 aires marines 4 National Marine Conservation Areas and 1 National Urban Park nationales de conservation et 1 parc urbain national du Canada •– National Park •– National Historic Site – National Marine Conservation Area •– National Urban Park •– Parc national •– Lieu historique national – Aire marine nationale de conservation •– Parc urbain national Newfoundland and New Brunswick Ontario Manitoba British Columbia Terre-Neuve-et- Nouveau-Brunswick Ontario Manitoba Colombie-Britannique Labrador Labrador 49 Kouchibouguac 93 Glengarry Cairn 138 York Factory 179 Yoho 49 Kouchibouguac 93 Cairn-de-Glengarry 138 York Factory 179 Yoho 1 Torngat Mountains 50 Fort Gaspareaux 94 Sir John Johnson House 139 Wapusk 180 Rogers Pass 1 Monts-Torngat 50 Fort-Gaspareaux 94 Maison-de- 139 Wapusk 180 Col-Rogers 2 Hopedale Mission 51 Monument-Lefebvre 95 Inverarden House 140 Prince of Wales Fort 181 Mount Revelstoke 2 Mission-de-Hopedale 51 Monument-Lefebvre Sir-John-Johnson 140 Fort-Prince-de-Galles 181 Mont-Revelstoke 3 Akami–uapishk u- 52 Fort Beauséjour–Fort 96 Laurier House 141 Lower Fort Garry 182 Glacier 3 Akami–uapishk u- 52 Fort-Beauséjour–Fort- 95 Maison-Inverarden 141 Lower Fort Garry 182 Glaciers KakKasuak-Mealy Cumberland 97 Rideau Canal 142 St. Andrew’s Rectory 183 Kicking Horse Pass KakKasuak-Monts-Mealy Cumberland 96 Maison-Laurier 142 Presbytère-St. Andrew’s 183 Col-Kicking Horse 207 Mountains (Reserve) 53 La Coupe Dry Dock -

Canada's 44 National Parks, 167 National Historic Sites and 4

Canada’s 44 National Parks, 167 National Historic Sites Les 44 parcs nationaux, 167 lieux historiques nationaux and 4 National Marine Conservation Areas et 4 aires marines nationales du Canada •– National Park •– National Historic Site – National Marine Conservation Area Halifax Citadel National Historic Site / •– Parc national •– Lieu historique national – Aire marine nationale de conservation Lieu historique national de la Citadelle-d’Halifax Newfoundland and Quebec Manitoba Yukon Terre-Neuve-et- Île-du-Prince-Édouard Ontario Alberta Labrador Labrador 58 Forillon 136 York Factory 198 S.S. Klondike 42 Ardgowan 92 Cairn-de-Glengarry 159 Lac-La Grenouille 1 Torngat Mountains 59 Mingan Archipelago 137 Wapusk 199 Kluane (National Park and 1 Monts-Torngat 43 Port-la-Joye–Fort-Amherst 93 Maison-de-Sir-John- 160 Elk Island 2 Hopedale Mission (Reserve) 138 Prince of Wales Fort Reserve) 2 Mission-de-Hopedale 44 Province House Johnson 161 Lacs-Waterton 3 Red Bay 60 Battle of the Restigouche 139 Lower Fort Garry 200 Dawson Historical Complex 3 Red Bay 45 Dalvay-by-the-Sea 94 Maison-Inverarden 162 Premier-Puits-de-Pétrole- 4 L’Anse aux Meadows 61 Pointe-au-Père Lighthouse 140 St. Andrew’s Rectory 201 Dredge No. 4 4 L’Anse aux Meadows 46 Cavendish-de-L.-M.- 95 Maison-Laurier de-l’Ouest-Canadien 5 Port au Choix 62 Saguenay–St. Lawrence 141 Forts Rouge, Garry 202 Former Territorial Court 5 Port au Choix Montgomery 96 Canal-Rideau 163 Ranch-Bar U 6 Gros Morne Marine Park and Gibraltar House 6 Gros-Morne 47 Île-du-Prince-Édouard 97 Blockhaus-de-Merrickville 164 Musée-du-Parc-Banff 7 Terra Nova 63 Fort Témiscamingue 142 Riel House 203 S.S. -

Hidden Gems in Yoho and Glacier National Parks

Get off the beaten track; Find the hidden gems in Yoho and Glacier National Parks Experience alpine lakes, waterfalls, historic sites, and stunning scenery – but without the crowds. Visit in late summer or fall when visitor numbers diminish, and higher elevation trails are still accessible. DAY 1: Get ready for your parks experience You'll find a wide variety of accommodations for your stay in Golden, including cozy cabins and rustic charming mountain chalets, slope-side condos, luxury vacation homes, hotels, and welcoming bed and breakfasts, for a truly authentic mountain experience. After checking in, head into town for those last-minute essentials and dinner at one of the many restaurants or pubs. After dinner, you could be relaxing in a hot tub and planning your days at the heart of the parks. The Golden Hiking Maps map includes maps of Yoho and Glacier National Parks, as well as hikes in and around Golden and Kicking Horse Mountain Resort. Find it at the Visitor Info Centre or at other locations in town. Hints & Tips: ● Purchase your Parks pass at the information centres in Field, Rogers Pass or once you arrive in Golden at the Golden Visitor Centre. ● Leave early to avoid busy parking lots. ● Always carry a first aid kit and bear spray and pack adequate food, water clothing, maps, and gear. ● Get updates on trail conditions from Parks Canada website or visitor information centres. Glacier National Park Trail Conditions report Yoho National Park Trail Conditions report DAY 2: Emerald Lake & Basin in Yoho National Park Your options include: Emerald Lake -The parking lot and first 500m of the trail may be busy, but once the bus tour visitors turn back you will enjoy a gentle, lakeshore trail surrounded by mountain and glacier views. -

Nisga'a Memorial Lava Bed Park) (The Memorial Park) for Approximately 12 Km

July 31, 2014 TransCanada Corporation 450 – 1st Street S.W. Calgary, AB, Canada T2P 5H1 Brian Bawtinheimer Parks Planning and Management Branch www.transcanada.com Parks and Protected Areas Division PO Box 9398 Stn Prov Gov Victoria, BC V8W 9M9 Dear Sir: Re: Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Project (Project) Stage 2 Application to Adjust the Boundaries of the Nisga’a Memorial Lava Bed Park Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Ltd. files with BC Parks the attached the Stage 2 Application to Adjust the Boundaries of the Nisga’a Memorial Lava Bed Park for the Project. If you have any questions or require additional information, please contact me at (403) 920-7385. Sincerely, Marilyn Carpenter Director, Environmental and Regulatory Permitting Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Ltd. Stage 2 Park Boundary Adjustment Application Nisga’a Memorial Lava Bed Park PRGT0004776-TC-BCP-RE-VA-0002 July 31, 2014 Rev 0 Revision 0 Final PRGT004776-TC-BCP-RE-VA-0002 July 31, 2014 Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Ltd. Stage 2 Park Boundary Adjustment Application Nisga’a Memorial Lava Bed Park Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 APPLICATION .......................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROJECT OVERVIEW AND ANTICIPATED PROJECT SCHEDULE .................................... 3 3.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE MEMORIAL PARK AND ITS VALUES ............................................. 4 3.1 Role and Goals ...................................................................................................4 3.2 -

Conserving Skeena Fish Populations and Their Habitat 2002

Conserving Skeena Fish Populations and their Habitat Allen S. Gottesfeld, Ken A. Rabnett, and Peter E. Hall November, 2002 Skeena Fisheries Commission Box 229, Hazelton, BC 250 842-5670 © Skeena Fisheries Commission 2002 The authors’ opinions do not necessarily reflect the policies of the Skeena Fisheries Commission. Comments, corrections, omissions, and information updates are welcome and may be forwarded to the authors. Cover: Coho at Stephens Creek, Kispiox Watershed September 2001. Photo Credit: A. S. Gottesfeld Back Cover: Skeena Watershed Map, Scale 1:2,000,000 Cartography by Gordon Wilson, Gitxsan Watershed A uthorities GIS Dept. Skeena Stage I Watershed-based Fish Sustainability Plan Conserving Skeena Fish Populations and Their Habitat Allen S. Gottesfeld, Ken A. Rabnett, and Peter E. Hall Skeena Fisheries Commission Table of Contents Abstract...................................................................................................................1 The Skeena WFSP Process.....................................................................................2 Context................................................................................................................2 Scope.......................................................................................................................3 Skeena WFSP Planning Process.............................................................................4 Stage I: Establishing Skeena Watershed Priorities.................................................5 Biophysical Profile: -

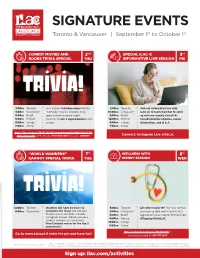

Trivia! Trivia!

SIGNATURE EVENTS Toronto & Vancouver | September 1st to October 1st COMEDY MOVIES AND 2nd SPECIAL ILAC IC 3rd BOOKS TRIVIA SPECIAL THU INFORMATIVE LIVE SESSION FRI TRIVIA! 7:00PM Toronto Join author @Alishasevigny for this 1:00PM Toronto Join our informative live with 4:00PM Vancouver “Comedy” movies & books trivia 10:00AM Vancouver ILAC an IC team member to catch 8:00PM Brazil special and fun social night! 2:00PM Brazil up with our weekly Covid-19/ 6:00PM Mexico Chances to win a signed book by the 12:00PM Mexico Canada boarder updates, events 2:00AM Turkey* author. 8:00PM Turkey information, and Q & A. 7:00AM China* 1:00AM China* https://ilac.zoom.us/j/87957682416?pwd=eksweHBnZHQ5UEpIdTVD RUpLc0xnUT09 or Meeting ID: 879 5768 2416 Passcode: COMEDY Connect: Instagram Live @ilac.ic “WORLD WONDERS” 7th WELLNESS WITH 8th KAHOOT SPECIAL TRIVIA TUE WENDY SESSION WED TRIVIA! 12:00PM Toronto Students will have 24 hours to 5:00PM Toronto Life after Covid-19? The new normal 9:00AM Vancouver complete this trivia! We will post 2:00PM Vancouver and how to deal with it with ILAC’s the pin access on @ilac_canada 6:00PM Brazil registered Nurse Wendy Mohammed. Instagram stories. Please use your 4:00PM Mexico #TogetherWithILAC student number as a nickname. 12:00AM Turkey* Free Cineplex movie for the top 3 contestants! 5:00AM China* https://us02web.zoom.us/j/9887818265 or Go to www.kahoot.it enter the pin and have fun! join using Meeting ID: 988 781 8265 ILAC is not the creator, organizer or owner of the events advertised and provided by third parties companies or outdoor activities suggestions.