Vernacular Architecture in Michigan's Upper Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keeping the Cottage in the Family

Keeping the Cottage in the Family A country place is a symbol of relaxation, continuity in life, and family harmony. But when the topic of ownership succession is raised, that lovely spot can be transformed into a source of stress, uncertainty and family strife Anthony Layton MBA, CIM August 2017 Keeping the Cottage in the Family | 1 Letter from Anthony Layton Cottage succession, along with other estate planning issues, is among my professional specialties. After decades of helping families confront and solve the cottage-succession problem, I decided to put pen to paper and document this knowledge. The result is Keeping the Cottage in the Family, a detailed review of everything a cottage owner should consider when contemplating what happens when it’s time to pass on the property to the next generation. A succession plan can only be produced with the help of seasoned professionals who are familiar with the many pitfalls common to this challenge. I would like to thank Tom Burpee, Morris Jacobson and Matthew Elder for sharing their considerable expertise in the preparation of this article. Sincerely, Anthony Layton MBA, CIM CEO and Portfolio Manager, PWL Capital Inc. Table of Contents A responsibility as well as a privilege .................... 6 The taxman must be paid, one way or another.............................................................. 12 Get a head start .................................................... 7 Owning through a trust ........................................ 12 Planning closer to the event................................... 8 Share-ownership agreements .............................. 13 The capital gains tax problem ............................... 9 Use of a nature conservancy .............................. 14 Use the exemption, or pay the tax? ...................... 9 Conclusion .......................................................... 14 A couple with two residences ............................... -

Wyncote, Pennsylvania: the History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1985 Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb Doreen L. Foust University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Foust, Doreen L., "Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb" (1985). Theses (Historic Preservation). 239. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/239 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Foust, Doreen L. (1985). Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/239 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Foust, Doreen L. (1985). Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and -

Cabins, Cottages, Pole Barns, Sheds, Outbuildings & More SHELDON

Cabins, Cottages, Pole Barns, Sheds, Outbuildings & More Spring - 2009 Copyright 2008 - Andrew Sheldon 8'-0" 8'-0" Plan #GH101 - 8' x 8' Greenhouse or Shed - $19 This little greenhouse is constructed on pressure treated skids making it mobile and in many communities it will be considered a temporary structure. It is constructed of 2x4's obtainable at any lumber yard. The roof glazing is a single sheet of acrylic, or if you prefer, the roof glass can be eliminated and the building used as a shed. A 2ft module makes the design easily expandable if the 8ft length does not fit your needs. A material list is included in the drawing. Additional or Reverse sets are $15.00 SHELDON DESIGNS, INC. Order by Phone: 800-572-5934 or by Fax: 609-683-5976 Page 1 Welcome ! My name is Andy Sheldon. I am an architect and have been designing small houses and farm buildings for over 25 years. My mission at SHELDON DESIGNS is to provide you with beautiful, economical, easy-to-build designs with complete blueprints at reasonable prices. This catalog contains some of my favorite small buildings. Each design that I offer specifies standard build- ing materials readily available at any lumber yard. When we receive your order, we will make every effort to pro- cess and ship within forty-eight hours. You should receive your detailed blueprints in approximately seven to ten days and your credit card will not be charged nor your check deposited until your plans are shipped. Your satisfaction is our highest priority. If you are dissatisfied in any way, you may return the order within 30 days for a full refund or exchange the plans for another de- sign. -

Digging Into a Dugout House (Site 21Sw17): the Archaeology of Norwegian Immigrant Anna Byberg Christopherson Goulson, Swenoda Township, Swift County, Minnesota

DIGGING INTO A DUGOUT HOUSE (SITE 21SW17): THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF NORWEGIAN IMMIGRANT ANNA BYBERG CHRISTOPHERSON GOULSON, SWENODA TOWNSHIP, SWIFT COUNTY, MINNESOTA \\|// \\|// \\|// \\|// TR1 North \\|// \\|// II \\|// |// \\ I IV |// | \\ VI \ // \\|// | TR2 North \\ // / Root \\|// \\|/ IVa \\|// II \\| / // \\|/ III I |// \\| \\ III VII Roots // XI \\|/ \|// XI XII / \ V IX VIII VIII VIII \\|// TU1 North \\|// IV \ \\|// \|// \\|// X V | \\|// XIII \\|/ \\|// \\ // VI III / \\|// \\|// \\|// \\|/ | \\|// VII / \\|// \\ // VIII I XIV IX III XI XII XV IV XVa II X IV Roots XVI III II VI VI V University of Kentucky Program for Archaeological Research Department of Anthropology Technical Report No. 480 May 2003 DIGGING INTO A DUGOUT HOUSE (SITE 21SW17): THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF NORWEGIAN IMMIGRANT ANNA BYBERG CHRISTOPHERSON GOULSON, SWENODA TOWNSHIP, SWIFT COUNTY, MINNESOTA Author: Donald W. Linebaugh, Ph.D., R.P.A. With Contributions by: Hilton Goulson, Ph.D. Tanya M. Peres, Ph.D., R.P.A. Renee M. Bonzani, Ph.D. Report Prepared by: Program for Archaeological Research Department of Anthropology University of Kentucky 1020A Export Street Lexington, Kentucky 40506-9854 Phone: (859) 257-1944 Fax: (859) 323-1968 www.uky.edu/as/anthropology/PAR Technical Report No. 480 ________________________________________ Donald W. Linebaugh, Ph.D., R.P.A. Principal Investigator May 15, 2003 i ABSTRACT This report presents the results of excavations on the dugout house site (21SW17) of Anna Byberg Christopherson Goulson in west-central Minnesota. The work was completed by Dr. Donald W. Linebaugh of the University of Kentucky and a group of family volunteers between June 6 and 12, 2002. Anna and Lars Christopherson reportedly moved into their dugout house ca. 1868. Lars and two of the five Christopherson children died of scarlet fever ca. -

2018 Holiday Cottage Brochure

HOLIDAY COT TAGES History, adventure, enjoyment. All on your doorstep. English Heritage cares for over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places – from world-famous prehistoric sites to grand medieval castles, from Roman forts on the edge of an empire to a Cold War bunker. Through these, we bring the story of England to life for over 10 million visitors each year. The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. www.english-heritage.org.uk English Heritage, The Engine House, Fire fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH Cover image: Dover Castle 23996/BD4408/JAN18/PAR5000 WEST OF ENGLAND A PENDENNIS CASTLE Callie’s Cottage 6 The Custodian’s House 8 B ST MAWES CASTLE Fort House 10 C WITLEY COURT & GARDENS Pool House 12 SOUTH OF ENGLAND D CARISBROOKE CASTLE The Bowling Green Apartment 16 E OSBORNE Pavilion Cottage 18 N No 1 Sovereign’s Gate 20 No 2 Sovereign’s Gate 22 F BATTLE ABBEY South Lodge 24 G DOVER CASTLE M L The Sergeant Major’s House 26 Peverell’s Tower 28 H WALMER CASTLE & GARDENS Garden Cottage 30 K The Greenhouse Apartment 32 EAST OF ENGLAND J I AUDLEY END C HOUSE & GARDENS I Cambridge Lodge 36 EAST MIDLANDS H F G J KIRBY HALL D Peacock Cottage 40 E K HARDWICK OLD HALL B A East Lodge 42 NORTH YORKSHIRE L RIEVAULX ABBEY SYMBOL GUIDE Refectory Cottage 46 M MOUNT GRACE PRIORY, COTTAGES PROPERTY FACILITIES NEARBY HOUSE AND GARDENS Prior’s Lodge 48 Dogs (max 2 well-behaved) Events Pub Travel Cot/Highchair Tearoom Coast NORTHUMBERLAND Barbeque Shop Shops Wood Burner Children’s Play Area Train Station N LINDISFARNE PRIORY Wi-Fi Wheelchair Access Coastguard’s Cottage 52 Join us on social media englishheritageholidaycottages @EnglishHeritage All cottages are equipped with TV/DVD, washer/tumble dryer, dishwasher and microwave. -

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

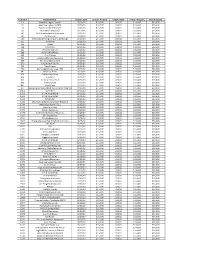

2021-02-09 Final Disbursement Spreadsheet

License # Establishment Check 1 Date Check 1 Amount Check 2 Date Check 2 Amount Total Awarded 51 American Legion Post #1 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 59 American Legion Post #28 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 74 Pancho's Villa Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 83 Asia GarDens/BranDy's 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 107 Bella Vista Pizzaria & Restaurant 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 140 The Blue Fox 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 200 Matanuska Brewing ComPany, Anchorage 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 217 Williwaw 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 225 Koots 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 258 Club Paris 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 321 Chili's Bar anD Grill 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 398 Buffalo WilD Wings 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 434 Fiori D'Italia 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 629 La Cabana Mexican Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 635 Serrano's Mexican Grill 11/12/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 670 Long Branch Saloon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 733 Twin Dragon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 750 Anchorage Moose LoDge 1534 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 761 MulDoon Pizza 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 814 The BraDley House 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 826 Tequila 61 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 842 The New Peanut Farm 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 888 Pizza OlymPia 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 891 Pizza Plaza 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 Anchorage977 Brewing ComPany (NeeD sPecial email if aPPlieD for Tier11/05/20 A) $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1064 Sorrento's 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1203 V.F.W. -

A Historical Note

A Historical Note We have included the information on this page to show you the original procedure that the Sioux used to determine the proper tripod pole measurements. If you have a tipi and do not know what size it is (or if you lose this set up booklet) you would use the method explained on this page to find your exact tripod pole lengths. It is simple and it works every time. We include this page only as an interesting historical reference. You will not need to follow the instructions on this page. The complete instructions that you will follow to set up your Nomadics tipi begin on page 4. All the measurements you will need are already figured out for you starting on page 5. -4”- In order to establish the proper position and length for the door pole, start at A and walk around the edge of the tipi cover to point B. Walk toe-to-heel one foot in front of the other and count your steps from A to B. Let us say for instance that you count 30 steps from A to B. Simply divide 30 by 1/3. This gives you 10. That means that you start again at A and walk toe-to- heel around the edge of the tipi cover 10 steps, going towards B again. Stop at 10 steps and place the end of the door pole (D) at that point on the edge of the tipi cover. Your three tripod poles should now look like the drawing above. The north and south poles going side by side down the middle of the tipi cover, the door pole placed 1/3 of the way from A to B, and the door pole crossing the north and south poles at Z. -

Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture

Anno 1778 m # # PHILLIPS ACADEMY # # # OLIVER-WENDELL- HOLMES # # # LIBRARY # # # # Lulie Anderson Fuess Fund The discovery and recording of the “vernacular” architec¬ ture of the Americas was a unique adventure. There were no guide books. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s search involved some 15,000 miles of travel between the St. Lawrence River and the Antilles by every conceivable means of transportation. Here in this handsome volume, illustrated with 105 photo¬ graphs and 21 drawings, are some of the amazing examples of architecture—from 1600 on—to be found in the Americas. Everybody concerned with today’s problems of shelter will be fascinated by the masterly solutions of these natural archi¬ tects who settled away from the big cities in search of a us architecture is a fascinating happier, freer, more humane existence. various appeal: Pictorially excit- ly brings native architecture alive is many provocative insights into mericas, their culture, the living and tradition. It explores, for the )f unknown builders in North and litectural heritage. Never before the beautiful buildings—homes, nills and other structures—erected architects by their need for shelter 3 settlers brought a knowledge of irt of their former cultures and their new surroundings that they ures both serviceable and highly art. The genius revealed in the ptation of Old World solutions to sibyl moholy-nagy was born and educated in Dresden, Ger¬ choice of local materials; in com- many. In 1931 she married the noted painter, photographer ationships might well be the envy and stage designer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. After living in Hol¬ land and England, they settled in Chicago where Moholy- Nagy founded the Institute of Design for which Mrs. -

The Carlsons at Home in Estonia, 1926-1937

The Carlsons: At Home in Estonia U.S. Consul Harry E. Carlson (Eesti Filmiarhiiv) U.S. Consul Harry E. Carlson and his wife Laura Reynert Carlson were two early fans of Estonia. While the normal tour of duty for a U.S. Consul was just two years, the Carlsons spent almost eleven years in Tallinn from 1926 to 1937. They liked life in Estonia so much that they kept summer homes in Haapsalu and Valgejõe where they spent their weekends and summers just like many Estonian couples. Making Estonia into a real family home, Harry and Laura's son Harry Edwin Reynert Carlson was born in Tallinn on October 21, 1927 – thereby setting a precedent which many U.S. diplomats have since followed. Harry Jr.'s sister Margaret Elisabeth Reynert Carlson was born here several years later on January 30, 1932. The Carlson's made themselves at home in Estonia in many other ways. Harry was a well-known fisherman and went fishing every chance he got. On February 1, 1937, Rahvaleht described Harry as belonging to a "family of famous sports fishermen." Like many Americans, Harry also liked to drive – he would take his car and drive his family all across Estonia to fish or spend time in the country-side. According to Postimees (May 5, 1932), one of the Carlsons' favorite places was Rõuge in southern Estonia near the town of Võru. By the end of his extended tour in Estonia, Harry seemed to have developed a particular affinity for Estonian summers. During his farewell interview to Uus Eesti (January 21, 1937), Harry was quoted as saying: "Estonia is not so rich in nature and the climate here is not that pleasant either, but the short Estonian summer is very appealing." By the time the Carlsons left for their onward assignment in London on February 1, 1937, they seem to have adjusted quite well to life in Estonia. -

COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd

2558 Schillinger Rd. • 219-7761 COFFEE, SMOOTHIES, LUNCH & BEERS. CHUCK’S FISH ($$) 966 Government St.• 408-9001 LAID-BACK EATERY & FISH MARKET 3249 Dauphin St. • 479-2000 5460 Old Shell Rd. • 344-4575 SEAFOOD AND SUSHI BAMBOO 1477 Battleship Pkwy. • 621-8366 FOY SUPERFOODS ($) 551 Dauphin St.• 219-7051 STEAKHOUSE & SUSHI BAR ($$) RIVER SHACK ($-$$) 119 Dauphin St.• 307-8997 SERDA’S COFFEEHOUSE ($) TRADITIONAL JAPANESE WITH HIBACHI GRILLS SEAFOOD, BURGERS & STEAKS COFFEE, LUNCHES, LIVE MUSIC & GELATO CORNER 251 ($-$$) 650 Cody Rd. S • 300-8383 6120 Marina Dr. • Dog River • 443-7318 GULF COAST EXPLOREUM CAFE ($) 3 Royal St. S. • 415-3000 HIGH QUALITY FOOD & DRINKS BANGKOK THAI ($-$$) THE GRAND MARINER ($-$$) HOMEMADE SOUPS & SANDWICHES 1539 US-98 • Daphne • 517-3963 251 Government St • 432-8000 DELICIOUS, TRADITIONAL THAI CUISINE 65 Government St. • 208-6815 28600 US 98 • Daphne • 626-5286 LOCAL SEAFOOD & PRODUCE DAUPHIN’S ($$-$$$) 6036 Rock Point Rd. • 443-7540 $10/PERSON • $$ 10-25/PERSON • $$$ OVER 25/PERSON SHELL FOOD MART ($) 3821 Airport Blvd. • 344-9995 HOOTERS ($) Co. Rd. 49 & U.S. 98• Magnolia Springs HIGH QUALITY FOOD WITH A VIEW 3869 Airport Blvd. • 345-9544 107 St. Francis St/RSA Building • 444-0200 BANZAI JAPANESE THE HARBOR ROOM ($-$$) COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd. • 661-9117 SIMPLY SWEET ($) RESTAURANT ($$) UNIQUE SEAFOOD 28975 US 98 • Daphne • 625-3910 CUPCAKE BOUTIQUE DUMBWAITER ($$-$$$) TRADITIONAL SUSHI & LUNCH. 64 S. Water St. • 438-4000 9 Du Rhu Dr. Suite 201 ALL SPORTS BAR & GRILL ($) 6207 Cottage Hill Rd. Suite B • 665-3003 312 Schillinger Rd./Ambassador Plaza• 633-9077 3408 Pleasant Valley Rd. • 345-9338 JAMAICAN VIBE ($) 167 Dauphin St. -

Beaches & Holiday Homes Dog-Friendly Directory

South Devon LOVES DOGS A pet-friendly holiday guide from Coast & Country Cottages Alfie Bear visits Salcombe TipsHoliday from advice local from vets, experts bloggers and The National Farmers’ Union The best forBeaches you and your & four-leggedholiday homes friend Dog-friendlyOver 100 eateries, attractionsdirectory and useful contacts SOUTH DEVON LOVES DOGS Welcome I’m Alfie, an English Springer Spaniel… Water obsessed and beach mad! I am always on the road with my human, sniffing out the very best in all things dog-friendly. Being a famous blogger allows me and my best friend Emma to travel around the country, going to prestigious events such as Crufts and staying in luxury properties like Poll Cottage in the heart of Salcombe. Together, Emma and I find our favourite dog-friendly locations, that our followers love to read about. Emma Bearman is a freelance Personally, I love Devon; it is the perfect place for a doggy photographer based in the holiday. With so many beaches to explore, I know I will Warwickshire countryside. have the best adventures. We always have to take a trip to Emma’s photographs of her beloved canine pal ‘Alfie Bear’, East Portlemouth, with miles of sandy beach and endless quickly turned into a full-time swimming. I love stopping at our favourite pub, The Victoria job and fully functioning online Inn, for a bite to eat on the way home. blog with thousands of fans visiting www.alfiebear.com. Alfie Bear Star of dog blog alfiebear.com We know how lucky we are to live and work in this Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty