Cultural Resources Overview Desert Peaks Complex of the Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks National Monument Doña Ana County, New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interpretation of the Structural Geology of the Franklin Mountains, Texas Earl M

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/26 An interpretation of the structural geology of the Franklin Mountains, Texas Earl M. P. Lovejoy, 1975, pp. 261-268 in: Las Cruces Country, Seager, W. R.; Clemons, R. E.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 26th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 376 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1975 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Prehistoric Trackways National Monument Recreation Area Management Plan

October 2020 Prehistoric Trackways National Monument Recreation Area Management Plan Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-NM-L0000-2021-0004-EA Las Cruces District Office 1800 Marquess Street Las Cruces, New Mexico 88005 575-525-4300 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Purpose and Need ........................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Decision to Be Made ....................................................................................................... 1 1.3. RAMP Planning Process ................................................................................................ 3 1.4. Plan Conformance and Relationship to Statutes and Regulations ............................ 3 1.4.1. Plan Conformance ..................................................................................................... 3 1.4.2. Relationship to Statutes and Regulations .................................................................. 5 1.5. Scoping and Issues .......................................................................................................... 6 1.5.1. Internal Scoping ........................................................................................................ 6 1.5.2. Internal and External Scoping ................................................................................... 7 1.5.3. Issues ........................................................................................................................ -

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

Late Paleozoic Tectonic and Sedimentologic History of the Penasco Uplift, North-Central New Mexico

RICE UNIVERSITY LATE PALEOZOIC TECTONIC AND SEDIMENTOLOGIC HISTORY OF THE PENASCO UPLIFT, NORTH-CENTRAL NEW MEXICO by ROY DONALD ADAMS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: 0^ (3- /jtd&i obfe B. Anderson, Chairman Assistant Professor pf Geology KT Rudy R. Schwarzer, Adjunct Assistant Professor of GSology John /E. Warme Professor of Geology Donald R. Baker Professor of Geology Houston, Texas May, 1980 ABSTRACT LATE PALEOZOIC TECTONIC AND SEDIMENTOLOGIC HISTORY OF THE PENASCO UPLIFT, NORTH-CENTRAL NEW MEXICO Roy Donald Adams The Paleozoic Peiiasco Uplift, located on the site of the present Nacimiento Mountains of north-central New Mexico, acted as a sediment source and modifier of regional sedimentation patterns from Middle Pennsylvanian to Early Permian time. The earliest history of the uplift is still poorly defined. Orogenic activity may have started as early as the Late Mississippian, or there may have been quiescence until after deposition of the Morrow-age Osha Canyon Formation and prior to deposition of the Atoka-age Sandia Formation. Coarse, arkosic siliciclastic sediments inter- bedded with fossilferious carbonates in the Madera Formation indicate that by early Desmoinesian time the Peiiasco Uplift had risen sufficiently to expose and erode Precambrian rocks. Paleotransport indicators in the arkosic sediments show transport away from the uplift. Throughout the remainder of the Pennsylvanian, the Peiiasco Uplift was a sediment source. The siliciclastic sediments derived from the Peiiasco Uplift formed a wedge that prograded out onto and interfingered with carbonate sediments of a shallow normal marine shelf. A change in paleotransport directions from northeasterly to southwesterly occurs on the east side of the Peiiasco Uplift and is due to the arrival of a flood of siliciclastic sediments derived from the Uncompahgre-San Luis Uplift to the northeast. -

Upper Paleozoic and Cretaceous Stratigraphy of the Hidalgo County Area, New Mexico Eugene Greenwood, F

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/21 Upper Paleozoic and Cretaceous stratigraphy of the Hidalgo County area, New Mexico Eugene Greenwood, F. E. Kottlowski, and A. K. Armstrong, 1970, pp. 33-44 in: Tyrone, Big Hatchet Mountain, Florida Mountains Region, Woodward, L. A.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 21st Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 176 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1970 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

By Douglas P. Klein with Plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado

U.S DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein with plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado Open-file Report 95-506 1995 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. The use of trade, product, or firm names in this papers is for descriptive purposes only, and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................. 1 DEEP SEISMIC CRUSTAL STUDIES .................................. 4 SEISMIC REFRACTION DATA ....................................... 7 RELIABILITY OF VELOCITY STRUCTURE ............................. 9 CHARACTER OF THE SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTION ..................... 13 DRILL HOLE DATA ............................................... 16 BASIN DEPOSITS AND BEDROCK STRUCTURE .......................... 20 Line 1 - Playas Valley ................................... 21 Cowboy Rim caldera .................................. 23 Valley floor ........................................ 24 Line 2 - San Luis Valley through the Alamo Hueco Mountains ....................................... 25 San Luis Valley ..................................... 26 San Luis and Whitewater Mountains ................... 26 Southern -

A Proposed Low Distortion Projection for the City of Las Cruces and Dona Ana County Scott Farnham, PE, PS City Surveyor, City of Las Cruces NM October 2020

A Proposed Low Distortion Projection for the City of Las Cruces and Dona Ana County Scott Farnham, PE, PS City Surveyor, City of Las Cruces NM October 2020 Introduction As part of the ongoing modernization of the U.S. National Spatial Reference System (NSRS), the National Geodetic Survey (NGS) will replace our horizontal and vertical datums (NAD83 and NAVD88) with new geometric datums assigned in the North American Terrestrial Reference Frame of 2022 (NATRF2022). The City of Las Cruces / Dona Ana County and the City of Albuquerque / Bernalillo County submitted proposals to NGS to incorporate Low Distortion Projections (LDP) as part of the New Mexico State Plane Coordinate Systems. Approval by NGS was obtained on June 17, 2019 for the proposed systems (see approval notice). Design of the LDP is the responsibility of the submitting agencies and must be submitted to NGS on or prior to March 31, 2021. Mark Marrujo1 with NMDOT is submitting final LDP design forms to NGS for the State of New Mexico. The City of Las Cruces (City) is designing a new Low Distortion Projection for Public Works Department, Engineering and Architecture projects to NGS criteria. To meet NGS LDP minimum size and shape criterion, the LDP area extends to Dona Ana County (County) boundary lines. This report presents design analysis and conclusions of the proposed City / County local NGS LDP system for stakeholders’ review prior to NGS final design submittal. NGS NM SPCS2022 Zones and Stakeholder Organizations NGS is designing new State Plane Coordinate Systems (SPCS2022) for New Mexico. The default SPCS2022 designs for the State are a statewide single zone and the three State Plane Zones: West, Central, and East. -

The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/63 The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, Karl Krainer, Dan S. Chaney, William A. DiMichele, Sebastian Voigt, David S. Berman, and Amy C. Henrici, 2012, pp. 345-376 in: Geology of the Warm Springs Region, Lucas, Spencer G.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Lueth, Virgil W.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Krainer, Karl, New Mexico Geological Society 63rd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 580 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2012 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. -

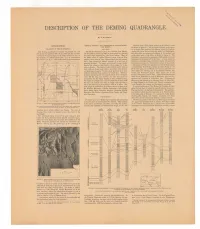

Description of the Deming Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE DEMING QUADRANGLE, By N. H. Darton. INTRODUCTION. GENERAL GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHWESTERN Paleozoic rocks. The general relations of the Paleozoic rocks NEW MEXICO. are shown in figure 3. 2 All the earlier Paleozoic rocks appear RELATIONS OF THE QUADRANGLE. STRUCTURE. to be absent from northern New Mexico, where the Pennsyl- The Deming quadrangle is bounded by parallels 32° and The Rocky Mountains extend into northern New Mexico, vanian beds lie on the pre-Cambrian rocks, but Mississippian 32° 30' and by meridians 107° 30' and 108° and thus includes but the southern part of the State is characterized by detached and older rocks are extensively developed in the southern and one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's surface, an area, in mountain ridges separated by wide desert bolsons. Many of southwestern parts of the State, as shown in figure 3. The that latitude, of 1,008.69 square miles. It is in southwestern the ridges consist of uplifted Paleozoic strata lying on older Cambrian is represented by sandstone, which appears to extend New Mexico (see fig. 1), a few miles north of the international granites, but in some of them Mesozoic strata also are exposed, throughout the southern half of the State. At some places the and a large amount of volcanic material of several ages is sandstone has yielded Upper Cambrian fossils, and glauconite 109° 108° 107" generally included. The strata are deformed to some extent. in disseminated grains is a characteristic feature in many beds. Some of the ridges are fault blocks; others appear to be due Limestones of Ordovician age outcrop in all the larger ranges solely to flexure. -

Geology of the Central Organ Mountains Dona Aña County, New Mexico Thomas G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/26 Geology of the central Organ Mountains Dona Aña County, New Mexico Thomas G. Glover, 1975, pp. 157-161 in: Las Cruces Country, Seager, W. R.; Clemons, R. E.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 26th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 376 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1975 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Geologic Setting, Hydrology, and Geochemistry of the Hueco Tanks Geothermal Area, Texas and New Mexico

Geological Circular 81-1 APreliminaryAssessmentoftheGeologicSetting,Hydrology,andGeochemistyoftheHuecoTanksGeothermalArea,TexasandNewMexico Christopher D.Henry and James K.Gluck jointly published by Bureau of Economic Geology The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712 W. L.Fisher,Director and Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council Executive Office Building 411 West 13th Street, Suite 800 Austin, Texas 78701 Milton L. Holloway, Executive Director prime funding provided by Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council throughInteragency Cooperation Contract No.IAC(80-81)-0899 1981 Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Regional geologic setting 2 Origin and locationof geothermal waters 5 Hot wells 5 Source of heat and ground-water flow paths 5 Faults in geothermal area 9 Implications of geophysical data 15 Hydrology 16 Data availability 16 Water-table elevation 17 Substrate permeability 19 Geochemistry 22 Geothermometry 27 Summary 32 Acknowledgments 32 References 33 Appendix A. Well data 35 Appendix B. Chemical analyses Wl Appendix C. Well designations WJ Figures 1. Tectonic map of Hueco Bolson near El Paso, Texas 3 2. Wells in Hueco Tanks geothermal area 6 3. Measured andreported temperatures ( C) of thermal and nonthermal wells 7 4. Depth to bedrock, absolute elevation of bedrock, and inferred normal faults . 10 5. Generalized west-east cross sections in Hueco Tanks geothermal area . .11 6. Depth to water table, absolute elevation of water table, and water- table elevation contours 18 111 7. Percentages of gravel, sand, clay, and bedrock from driller's logs 21 8. Trilinear diagram of thermal and nonthermal waters 24 9. Total dissolved solids and chloride concentrations 25 Tables 1. Saturation indices 28 2. -

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past Series: No. 1—SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO No. 2—TAOS—RED RIVER—EAGLE NEST, NEW MEXICO, CIRCLE DRIVE No. 3—ROSWELL—CAPITAN—RUIDOSO AND BOTTOMLESS LAKES STATE PARK, NEW MEXICO No. 4—SOUTHERN ZUNI MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO No. 5—SILVER CITY—SANTA RITA—HURLEY, NEW MEXICO No. 6—TRAIL GUIDE TO THE UPPER PECOS, NEW MEXICO No. 7—HIGH PLAINS NORTHEASTERN NEW MEXICO, RATON- CAPULIN MOUNTAIN—CLAYTON No. 8—MOSlAC OF NEW MEXICO'S SCENERY, ROCKS, AND HISTORY No. 9—ALBUQUERQUE—ITS MOUNTAINS, VALLEYS, WATER, AND VOLCANOES No. 10—SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO No. 11—CUMBRE,S AND TOLTEC SCENIC RAILROAD C O V E R : REDONDO PEAK, FROM JEMEZ CANYON (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by John Whiteside) Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by Robert W . Talbott) WHITEWATER CANYON NEAR GLENWOOD SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, a n d History edited by PAIGE W. CHRISTIANSEN and FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES 1972 NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, President NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, Director BOARD OF REGENTS Ex Officio Bruce King, Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo, Superintendent of Public Instruction Appointed William G. Abbott, President, 1961-1979, Hobbs George A. Cowan, 1972-1975, Los Alamos Dave Rice, 1972-1977, Carlsbad Steve Torres, 1967-1979, Socorro James R.