Buddhist Perspectives on Sharing Wisdom, Sallie B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Taiwan's Tzu Chi As Engaged Buddhism

BSRV 30.1 (2013) 137–139 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (print) 0256-2897 doi: 10.1558/bsrv.v30i1.137 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (online) 1747-9681 Taiwan’s Tzu Chi as Engaged Buddhism: Origins, Organization, Appeal and Social Impact, by Yu-Shuang Yao. Global Oriental, Brill, 2012. 243pp., hb., £59.09/65€/$90, ISBN-13: 9789004217478. Reviewed by Ann Heirman, Oriental Languages and Cultures, Ghent University, Belgium. Keywords Tzu Chi, Taiwanese Buddhism, Engaged Buddhism Taiwan’s Tzu Chi as Engaged Buddhism is a well-written book that addresses a most interesting topic in Taiwanese Buddhism, namely the way in which Engaged Buddhism found its way into Taiwan in, and through, the Tzu Chi Foundation (the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation). Founded in 1966, the Foundation expanded in the 1990s, and so became the largest lay organiza- tion in a contemporary Chinese context. The overwhelming involvement of the laity introduced a new aspect, and has triggered major changes in Taiwanese Buddhism. The present book offers a most welcome comprehensive study of the Foundation, discussing its context, development, structure, teaching and prac- tices. With its focus on both the history and the social context, the work devel- ops an interesting interdisciplinary approach, offering valuable insights into the appeal of the movement to a Taiwanese public. Nevertheless, some remarks still need to be made. The work is based on research that was completed in 2001, and research updates have not been pro- duced since, apart from a small Afterword (pp. 228-230). Yet not publishing the present work would have been a loss to the scientific community. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

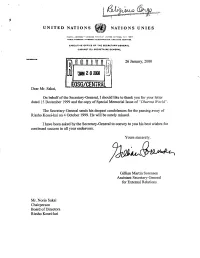

EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS ADRESSE POST ALE- UNITED NATIONS, N.V. 1OO17 CABLE AODflCSS ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: I/NATIONS NEWYORK EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL CABINET OU SECRETAIRE GENERAL REFERENCE: 26 January, 2000 EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr. Sakai, On behalf of the Secretary-General, I should like to thank you for your letter dated 15 December 1999 and the copy of Special Memorial Issue of "Dharma World". The Secretary-General sends his deepest condolences for the passing away of Rissho Kosei-kai on 4 October 1999. He will be surely missed. I have been asked by the Secretary-General to convey to you his best wishes for continued success hi all your endeavors. Yours sincerely, Gillian Martin Sorensen Assistant Secretary-General for External Relations Mr. Norio Sakai Chairperson Board of Directors Rissho Kosei-kai RISSHO KOSEI-KAI C, A BUDDHIST ORGANIZATION 2-11-1 Wada, Suginami-ku, Tokyo 166-8537, Japan, Tel: 03-3383-1111 lilJLU DEC 2 9 I999 December 15, 1999 Dear Sir/Madam, Special Memorial Issue of Dharrna World I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude for your friendship with Rissho Kosei-kai. As you may know, Founder Nikkyo Niwano peacefully passed away on October 4, 1999 at the age of 92. The enclosed Special Memorial Issue of Dharma World carries full details of the Founder's funeral ceremonies and a complete review of his life and work. I am very pleased to present this issue to you as a token of our wholehearted appreciation. Founder's posthumous name is "If^JLEIifc—SfbfcfiirlJ" (Kaiso Nikkyo Ichijo Daishi) in Japanese and "The Founder Nikkyo, Great Teacher of the One Vehicle" in English. -

Religion in the Age of Development

religions Article Religion in the Age of Development R. Michael Feener 1,* and Philip Fountain 2 1 Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, Marston Road, Oxford OX3 0EE, UK 2 Religious Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 20 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Religion has been profoundly reconfigured in the age of development. Over the past half century, we can trace broad transformations in the understandings and experiences of religion across traditions in communities in many parts of the world. In this paper, we delineate some of the specific ways in which ‘religion’ and ‘development’ interact and mutually inform each other with reference to case studies from Buddhist Thailand and Muslim Indonesia. These non-Christian cases from traditions outside contexts of major western nations provide windows on a complex, global history that considerably complicates what have come to be established narratives privileging the agency of major institutional players in the United States and the United Kingdom. In this way we seek to move discussions toward more conceptual and comparative reflections that can facilitate better understandings of the implications of contemporary entanglements of religion and development. Keywords: Religion; Development; Humanitarianism; Buddhism; Islam; Southeast Asia A Sarvodaya Shramadana work camp has proved to be the most effective means of destroying the inertia of any moribund village community and of evoking appreciation of its own inherent strength and directing it towards the objective of improving its own conditions. A.T. -

Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart

Coventry University Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart McGrew, L. Submitted version deposited in CURVE January 2014 Original citation: McGrew, L. (2011) Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University. Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. CURVE is the Institutional Repository for Coventry University http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart by Laura McGrew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Coventry University Centre for the Study of Peace and Reconciliation Coventry, United Kingdom April 2011 © Laura McGrew All Rights Reserved 2011 ABSTRACT Under the brutal Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 1979 in Cambodia, 1.7 million people died from starvation, overwork, torture, and murder. While five senior leaders are on trial for these crimes at the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia, hundreds of lower level perpetrators live amongst their victims today. This thesis examines how rural Cambodians (including victims, perpetrators, and bystanders) are coexisting after the trauma of the Khmer Rouge years, and the decades of civil war before and after. -

Caring for the Dead Ritually in Cambodia

Caring for the Dead Ritually in Cambodia John Cliff ord Holt* Buddhist conceptions of the after-life, and prescribed rites in relation to the dead, were modified adaptations of brahmanical patterns of religious culture in ancient India. In this article, I demonstrate how Buddhist conceptions, rites and dispositions have been sustained and transformed in a contemporary annual ritual of rising importance in Cambodia, pchum ben. I analyze phcum ben to determine its funda- mental importance to the sustenance and coherence of the Khmer family and national identity. Pchum ben is a 15-day ritual celebrated toward the end of the three-month monastic rain retreat season each year. During these 15 days, Bud- dhist laity attend ritually to the dead, providing special care for their immediately departed kin and other more recently deceased ancestors. The basic aim of pchum ben involves making a successful transaction of karma transfer to one’s dead kin, in order to help assuage their experiences of suffering. The proximate catalyst for pchum ben’s current popularity is recent social and political history in Southeast Asia, especially the traumatic events that occurred nationally in Cambodia during the early 1970s through the 1980s when the country experienced a series of convul- sions. Transformations in religious culture often stand in reflexive relationship to social and political change. Keywords: Cambodia, buddhism, Khmer Rouge, death, ritual, pchum ben, family, national identity Death is an inevitable fact of life. For the religious, its occurrence does not necessarily signal life’s end, but rather the beginning of a rite de passage, a transitional experience in which the newly dead leave behind the familiarity of human life for yet another mode of being beyond. -

Religious Pluralism, Globalization, and World Politics This Page Intentionally Left Blank Religious Pluralism, Globalization, and World Politics

Religious Pluralism, Globalization, and World Politics This page intentionally left blank Religious Pluralism, Globalization, and World Politics edited by thomas banchoff 1 2008 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2008 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Religious pluralism, globalization, and world politics / edited by Thomas Banchoff. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-19-532340-5; ISBN-13: 978-0-19-532341-2 (pbk.) i. Religions—Relations. 2. Religious pluralism. 3. Globalization. 4. International relations. I. Banchoff, Thomas F., 1964– BL 410.R44 2008 201'.5—dc22 2008002473 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Acknowledgments Few issues are more important and less understood than the role of religion in world affairs. -

Buddhism and Nonviolent Global Problem-Solving

Buddhism and Nonviolent Global Problem-Solving Ulan Bator Explorations BUDDHISM AND NONVIOLENT GLOBAL PROBLEM-SOLVING Ulan Bator Explorations Edited by Glenn D. Paige and Sarah Gilliatt Center for Global Nonviolence 2001 Copyright ©1991 by the Center for Global Nonviolence Planning Project, Spark M. Matsunaga Institute for Peace, University of Hawai'i, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96822. Copyright ©1999 by the nonprofit Center for Global Nonviolence, Inc., 3653 Tantalus Drive, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96822-5033. Website: www.globalnonviolence.org. Email: [email protected]. Copying for personal and educational use is encouraged by the copyright holders. Original publication was made possible by the generosity of the Korean Buddhist Dae Won Sa Temple of Hawai'i. Now Mu-Ryang-Sa (Broken Ridge Buddhist Temple), 2408 Halelaau Place, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96816. By gentle and skillful means based on reason. --From the Mongolian Buddhist tradition CONTENTS Preface Introduction 1 OPENING ADDRESS From Violent Combat to Playful Exchange of Flowers Khambo Lama Kh. Gaadan 7 PERSPECTIVES: BUDDHISM, LEADERSHIP, SCHOLARSHIP, ACTION Global Problem-Solving: A Buddhist Perspective Sulak Sivaraksa 15 The United Nations, Religion, and Global Problems: Facing a Crisis of Civilization Kinhide Mushakoji 33 Visioning a Peaceful World Johan Galtung 37 Nonviolent Buddhist Problem-Solving in Sri Lanka A.T. Ariyaratne 65 GLOBAL PROBLEM-SOLVING Five Principles for a New Global Moral Order Thich Minh Chau 91 The Importance of the Buddhist concept of Karma for World Peace Yoichi Kawada 103 Disarmament Efforts from the Standpoint of Mahayana Buddhism Yoichi Shikano 115 Buddhism and Global Economic Justice Medagoda Sumanatissa 125 "buddhism" and Tolerance for Diversity of Religion and Belief Sulak Sivaraksa 137 Nonviolent Ecology: The Possibilities of Buddhism Leslie E. -

Scriptural Continuity Between Traditional and Engaged Buddhism

SCRIPTURAL CONTINUITY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND ENGAGED BUDDHISM Jack Carman B.A., California State University, Fresno 1974 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in LIBERAL ARTS at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 © 2010 Jack Carman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii SCRIPTURAL CONTINUITY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND ENGAGED BUDDHISM A Thesis by Jack Carman Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Joel Dubois, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader Jeffrey Brodd, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Jack Carman I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Department Chair ___________________ Jeffrey Brodd, Ph.D. Date Liberal Arts Master’s Program iv Abstract of SCRIPTURAL CONTINUITY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND ENGAGED BUDDHISM by Jack Carman Engaged Buddhism is a modern reformist movement. It stirs debate concerning the scriptural and philosophical origins of Buddhist social activism. Some scholars argue there is continuity between traditional Buddhism and a rationale for social activism in engaged Buddhism. Other scholars argue that while the origins of social activism may be latent in the traditional scriptures, this latency cannot be activated until Asian Buddhism interacts with Western sociopolitical theory. In this thesis I present an overview of Buddhist fundamentals that are common to both traditional and engaged Buddhism, and I conduct a critical overview of three seminal Buddhist texts – The Dhammapada, The Edicts of Asoka, and Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland. I provide critical reviews of contemporary Buddhist scholars representing both the traditional and modernist schools. -

Vol.14 No.1 Jan.-Apr. 2541 (1998)

SEEDS OF PEACE Vol.14 No.1 Jan.-Apr. 2541 (1998) Special Issue On 'Alternatives to Consumerism' And Remembering Gandhi On His 50Th Death Anniversary SEEDS OF c 0 N T E N T Publisher 4 Editorial Notes Sulak Sivaraksa COUNTRY REPORTS Editor 5 BANGLADESH: Non-violence Training for Buddhist Women Br. Jarlath D'Souza Zarina Mulla 5 BURMA: Buddhist Women in Burma Martin Petrich 8 CAMBODIA: Toward an Environmental Ethic in SE Asia 9 INDIA: A Gandhian Seminar Towards Global Unity Br. Jarlath D'Souza Cover 9 INDONESIA: Seminar on Love in Action Yabin Pali verses by the Venerable P.O.Box 19 10 MALAYSIA: "Operation Lalang"- 10 Years Later Mahadthai P Somdech Maha 11 THAILAND: Buddhist Monks and Teachers Behind Most Child Assaults Bangkok 10 Ghosananda Tel./Fax [66 OUR ACTIVITIES E-mail: ineb Lay-out 12 Alternatives to Consumerism Gathering 1997 Pavel Gmuzdek Song Sayam. , Ltd. 18 Declaration on Alternatives to Consumerism: Draft The goals Tel. 662-225-9533-5 19 Declaration on Alternatives to Consumerism: Comments Jane Rasbaslz I. Promote 20 Sao Paulo Message of the Alliance for a Responsible and United World among Bu Published by 21 Creative Street Theatre James Andean Buddhist se 24 A Workshop: Self Reliance at the Grassroots Lillian Willoughby Buddhist gro /NEB 26 Natural Childhood Hans van Willensvaard 2. Facilitate Ph & Fax [66-2]433-7169 30 Yadana Pipeline Walks and Tree Ordination Todd Ansted many proble E-mail: [email protected] 33 Dharma Walks: Expressing Solidarity .,.,j,h Indigenous Peoples Zarina Mulla societies, and & 36 Letter to the Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai ATC Forest Walks Participants 3.