Caring for the Dead Ritually in Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Etiquette, Language & Culture

Business etiquette, language & culture Page 1 of 5 Business etiquette, language & culture Overview Khmer is the official language of Cambodia and is used by roughly 90% of the population. Due to the past colonial rule by France, a number of French words exist in the language. However, English is not widely understood, particularly amongst the older generation and in rural areas. Business cards should be translated into Cambodian and printed in English on one side and Cambodian on the other. Use the services of a professional translator (rather than translating online) – a list of translators and interpreters has been prepared by the British Embassy Phnom Penh for the convenience of British Nationals who may require these services and assistance in Cambodia, at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cambodia-list-of-translators-and- interpreters. As in China, business cards should be given and received with both hands and studied carefully. This is particularly important when dealing with Cambodia’s ethnic Chinese minority, many of whom hold influential positions in the country’s business community. The Cambodian culture is conservative and hierarchical, and Theravada Buddhism is practiced by 95% of the population. Followers adhere to the concept of collectivism – the idea that the family, neighbourhood and society is more important than the wishes of the individual – and as in many Asian cultures the sense of ‘face’ is also considered paramount. Consequently you should avoid causing public embarrassment, not lose your temper in public and strive to maintain a sense of harmony. As a sign of respect for western customs, handshakes are the norm between men, but it is not uncommon to greet women with the “Sampeah” – the placing of palms together in a prayer-like position at chest level, with a slight bow of the head. -

The Continuing Presence of Victims of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Today's

Powerful remains: the continuing presence of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime in today’s Cambodia HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Helen Jarvis Permanent People’s Tribunal, UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme [email protected] Abstract The Khmer Rouge forbade the conduct of any funeral rites at the time of the death of the estimated two million people who perished during their rule (1975–79). Since then, however, memorials have been erected and commemorative cere monies performed, both public and private, especially at former execution sites, known widely as ‘the killing fields’. The physical remains themselves, as well as images of skulls and the haunting photographs of prisoners destined for execution, have come to serve as iconic representations of that tragic period in Cambodian history and have been deployed in contested interpretations of the regime and its overthrow. Key words: Cambodia, Khmer Rouge, memorialisation, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, dark tourism Introduction A photograph of a human skull, or of hundreds of skulls reverently arranged in a memorial, has become the iconic representation of Cambodia. Since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime on 7 January 1979, book covers, film posters, tourist brochures, maps and sign boards, as well as numerous original works of art, have featured such images of the remains of its victims, often coupled with the haunting term ‘the killing fields’, as well as ‘mug shots’ of prisoners destined for execution. Early examples on book covers include the first edition of Ben Kiernan’s seminal work How Pol Pot Came to Power, published in 1985, on which the map of Cambodia morphs into the shape of a human skull and Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death, edited by Karl D. -

Newcambodia 1 HS

CULTUREGUIDE CAMBODIA SERIES 1 SECONDARY (7–12) Photo by Florian Hahn on Unsplash CAMBODIA CULTUREGUIDE This unit is published by the International Outreach Program of the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies at Brigham Young University as part of an effort to foster open cultural exchange within the educational community and to promote increased global understanding by providing meaningful cultural education tools. Curriculum Development Richard Gilbert has studied the Cambodian language and culture since 1997. For two years, he lived among the Cambodian population in Oakland, California. He was later priv- ileged to work in Cambodia during the summer of 2001 as an intern for the U.S. Embassy. He is fluent in Cambodian and is a certified Cambodian language interpreter. Editorial Staff Content Review Committee Victoria Blanchard, CultureGuide publica- Jeff Ringer, director tions coordinator International Outreach Cory Leonard, assistant director Leticia Adams David M. Kennedy Center Adrianne Gardner Ana Loso, program coordinator Anvi Hoang International Outreach Anne Lowman Sopha Ly, area specialist Kimberly Miller Rebecca Thomas Special Thanks To: Julie Volmar Bradley Bessire, photographer Audrey Weight Kirsten Bodensteiner, photographer Andrew Gilbert, photographer J. Lee Simons, editor Brett Gilbert, photographer Kennedy Center Publications Ian Lowman, photographer: Monks and New Age Shaman in Phnom Penh, Coconut Vender in Phnom Penh, Pediment on Eleventh Century Buddhist Temple, and Endangered Wat Nokor in Kâmpóng Cham For more information on the International Outreach program at Brigham Young University, contact International Outreach, 273 Herald R. Clark Building, PO Box 24537, Provo, UT 84604- 9951, (801) 422-3040, [email protected]. © 2004 International Outreach, David M. -

"The Collapse of Cambodian Democracy and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal"

TRANSCRIPT "The Collapse of Cambodian Democracy and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal" A conversation with Putsata Reang, Heather Ryan, and David Tolbert Moderator: Jim Goldston Recorded October 24, 2017 ANNOUNCER: You are listening to a recording of the Open Society Foundations, working to build vibrant and tolerant democracies worldwide. Visit us at OpenSocietyFoundations.org. JIM GOLDSTON: I'm Jim Goldston with the Open Society Justice Initiative, and we're very pleased to welcome you to this evening's-- (MIC NOISE) discussion on the collapse of Cambodian democracy and the Khmer Rouge tribunal. We have with us three great-- panelists who are gonna be looking at-- what has been happening in Cambodia and-- what has been the impact of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia-- in operation now for a decade. To my-- immediate right is David Tolbert, the president of the International Center for Transitional Justice, the former special expert to the U.N. secretary general on the E-triple-C, if I can call the Extraordinary Chambers that. And David brings, of course, a diverse range of experiences dealing with mass crimes in lots of places around the world. To his right is-- Putsata Reang, who is an author and journalist who's followed closely the work of the E-triple-C, and also broader developments-- in Cambodia. And to Putsata's right is Heather Ryan, a consultant with the Open Society Justice Initiative who has-- was based in Phnom Penh for quite some time, and has also monitored the court very, very closely. So we really have people who know what they're talking about, which is a good start for a great panel. -

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy Sophie Diamant Richardson Old Chatham, New York Bachelor of Arts, Oberlin College, 1992 Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia May, 2005 !, 11 !K::;=::: .' P I / j ;/"'" G 2 © Copyright by Sophie Diamant Richardson All Rights Reserved May 2005 3 ABSTRACT Most international relations scholarship concentrates exclusively on cooperation or aggression and dismisses non-conforming behavior as anomalous. Consequently, Chinese foreign policy towards small states is deemed either irrelevant or deviant. Yet an inquiry into the full range of choices available to policymakers shows that a particular set of beliefs – the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – determined options, thus demonstrating the validity of an alternative rationality that standard approaches cannot apprehend. In theoretical terms, a belief-based explanation suggests that international relations and individual states’ foreign policies are not necessarily determined by a uniformly offensive or defensive posture, and that states can pursue more peaceful security strategies than an “anarchic” system has previously allowed. “Security” is not the one-dimensional, militarized state of being most international relations theory implies. Rather, it is a highly subjective, experience-based construct, such that those with different experiences will pursue different means of trying to create their own security. By examining one detailed longitudinal case, which draws on extensive archival research in China, and three shorter cases, it is shown that Chinese foreign policy makers rarely pursued options outside the Five Principles. -

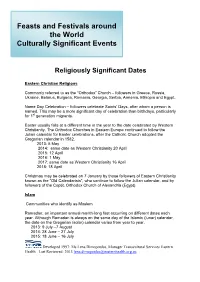

Feasts and Festivals Around the World Culturally Significant Events

Feasts and Festivals around the World Culturally Significant Events Religiously Significant Dates Eastern Christian Religions Commonly referred to as the “Orthodox” Church – followers in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia, Serbia, Armenia, Ethiopia and Egypt. Name Day Celebration – followers celebrate Saints’ Days, after whom a person is named. This may be a more significant day of celebration than birthdays, particularly for 1st generation migrants. Easter usually falls at a different time in the year to the date celebrated by Western Christianity. The Orthodox Churches in Eastern Europe continued to follow the Julian calendar for Easter celebrations, after the Catholic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582. 2013: 5 May 2014: same date as Western Christianity 20 April 2015: 12 April 2016: 1 May 2017: same date as Western Christianity 16 April 2018: 18 April Christmas may be celebrated on 7 January by those followers of Eastern Christianity known as the “Old Calendarists”, who continue to follow the Julian calendar, and by followers of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (Egypt). Islam Communities who identify as Moslem Ramadan: an important annual month-long fast occurring on different dates each year. Although Ramadan is always on the same day of the Islamic (lunar) calendar, the date on the Gregorian (solar) calendar varies from year to year. 2013: 9 July –7 August 2014: 28 June – 27 July 2015: 18 June – 16 July Developed 1997: Ms Lena Dimopoulos, Manager Transcultural Services Eastern Health Last Reviewed: 2013 [email protected] 2016: 6 June – 5 July 2017: 27 May – 25 July 2018: 16 May – 14 June New Year: some Moslems may fast during daylight hours. -

Hun Sen, the UN, and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Not Worth the Wait: Hun Sen, the UN, and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rh6566v Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 24(1) Author Bowman, Herbert D. Publication Date 2006 DOI 10.5070/P8241022188 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California NOT WORTH THE WAIT: HUN SEN, THE UN, AND THE KHMER ROUGE TRIBUNAL Herbert D. Bowman* I. INTRODUCTION Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge killed between one and three million Cambodians.1 Twenty-four years later, on March 17, 2003, the United Nations and the Cambodian govern- ment reached an agreement to establish a criminal tribunal de- signed to try those most responsible for the massive human rights violations which took place during the Khmer Rouge reign of terror. 2 Another three years later, on July 4, 2006, international and Cambodian judges and prosecutors were sworn in to begin work at the Extraordinary Chamber in the Courts of Cambodia ("ECCC"). 3 To quickly grasp the Cambodia court's prospects for success, one only need know a few basic facts. First, the jurisdiction of the court will be limited to crimes 4 that took place between April 17, 1975 and January 6, 1979. * Fellow of Indiana University School of Law, Indianapolis Center for Inter- national & Comparative Law. Former International Prosecutor for the United Na- tions Mission to East Timor. The author is currently working and living in Cambodia. 1. Craig Etcheson, The Politics of Genocide Justice in Cambodia, in INTERNA- TIONALIZED CRIMINAL COURTS: SIERRA LEONE, EAST TIMOR, Kosovo AND CAM- BODIA 181-82 (Cesare P.R. -

Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture

Thesis Title: Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture In fulfilment of the requirements of Master’s in Theology (Missiology) Submitted by: Gerard G. Ravasco Supervised by: Dr. Bill Domeris, Ph D March, 2004 Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The world we live in 1 1.2 The particular world we live in 1 1.3 Our target location: Cambodia 2 1.4 Our Particular Challenge: Cambodian Culture 2 1.5 An Invitation to Inculturation 3 1.6 My Personal Context 4 1.6.1 My Objectives 4 1.6.2 My Limitations 5 1.6.3 My Methodology 5 Chapter 2 2.0 Religious Influences in Early Cambodian History 6 2.1 The Beginnings of a People 6 2.2 Early Cambodian Kingdoms 7 2.3 Funan 8 2.4 Zhen-la 10 2.5 The Founding of Angkor 12 2.6 Angkorean Kingship 15 2.7 Theravada Buddhism and the Post Angkorean Crisis 18 2.8 An Overview of Christianity 19 2.9 Conclusion 20 Chapter 3 3.0 Religions that influenced Cambodian Culture 22 3.1 Animism 22 3.1.1 Animism as a Philosophical Theory 22 3.1.2 Animism as an Anthropological Theory 23 3.1.2.1 Tylor’s Theory 23 3.1.2.2 Counter Theories 24 3.1.2.3 An Animistic World View 24 3.1.2.4 Ancestor Veneration 25 3.1.2.5 Shamanism 26 3.1.3 Animism in Cambodian Culture 27 3.1.3.1 Spirits reside with us 27 3.1.3.2 Spirits intervene in daily life 28 3.1.3.3 Spirit’s power outside Cambodia 29 3.2 Brahmanism 30 3.2.1 Brahmanism and Hinduism 30 3.2.2 Brahmin Texts 31 3.2.3 Early Brahmanism or Vedism 32 3.2.4 Popular Brahmanism 33 3.2.5 Pantheistic Brahmanism -

Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart

Coventry University Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart McGrew, L. Submitted version deposited in CURVE January 2014 Original citation: McGrew, L. (2011) Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University. Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. CURVE is the Institutional Repository for Coventry University http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open Reconciliation in Cambodia: Victims and Perpetrators Living Together, Apart by Laura McGrew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Coventry University Centre for the Study of Peace and Reconciliation Coventry, United Kingdom April 2011 © Laura McGrew All Rights Reserved 2011 ABSTRACT Under the brutal Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 1979 in Cambodia, 1.7 million people died from starvation, overwork, torture, and murder. While five senior leaders are on trial for these crimes at the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia, hundreds of lower level perpetrators live amongst their victims today. This thesis examines how rural Cambodians (including victims, perpetrators, and bystanders) are coexisting after the trauma of the Khmer Rouge years, and the decades of civil war before and after. -

Tuchman-Rosta, Celia

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performance, Practice, and Possibility: How Large-Scale Processes Affect the Bodily Economy of Cambodia's Classical Dancers Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qb8m3cx Author Tuchman-Rosta, Celia Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Performance, Practice, and Possibility: How Large Scale Processes Affect the Bodily Economy of Cambodia’s Classical Dancers A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta March 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sally Ness, Chairperson Dr. Yolanda Moses Dr. Christina Schwenkel Dr. Deborah Wong Copyright by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta 2018 The Dissertation of Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of many inspiring individuals who have taken the time to guide my research and writing in small and large ways and across countries and oceans. To start, I thank Sophiline Cheam Shapiro and John Shapiro, co-founders of Khmer Arts, and Michael Sullivan the former director (and his predecessor Philippe Peycam) at the Center For Khmer Studies who provided the formal letters of affiliation required for me -

Cambodia's Dirty Dozen

HUMAN RIGHTS CAMBODIA’S DIRTY DOZEN A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals WATCH Cambodia’s Dirty Dozen A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36222 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36222 Cambodia’s Dirty Dozen A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals Map of Cambodia ............................................................................................................... 7 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Khmer Rouge-era Abuses ......................................................................................................... -

Thecambodiadaily

All the News Without Fear or Favor The Cambodia daily Volume 66 issue 5 Thursday, November 10, 2016 2,000 riel/50 cents Against All Trump Wins. Odds, Trump What Does It Triumphs in Mean for US Election Cambodia? ReuteRs By Sek OdOm U.S. Republican Donald Trump and matt SurruScO stunned the world by defeating the cambodia daily heavily favored hillary Clinton in Donald Trump’s victory in the Tuesday’s presidential election, end- U.S. presidential race yesterday ing eight years of Democratic rule shocked pollsters, political pundits and sending the U.S. on a new, un- and many Americans who had certain path. scoffed at their president-elect A wealthy real estate developer when he announced his candidacy and former reality television host, 17 months ago. Trump rode a wave of anger toward As a global audience digested Washington insiders to win the the news—it was clear by lunch - White house race against Clinton, time in Cambodia that Mr. Trump the Democratic candidate whose was headed for victory—Mom gold-plated establishment resume Sinath, 63, was sliding meatballs includes stints as a first lady, U.S. onto a skewer to sell to passersby senator and secretary of state. outside the Royal Pal ace in Phnom Worried a Trump victory could Penh. cause economic and global uncer- Despite having a daughter and tainty, investors were in full flight three granddaughters living in from risky assets such as stocks, Long Beach, California, she said and the U.S. dollar sank. U.S. stock she wasn’t paying any attention to futures dived 5 percent at one point, the election half a world away.