Tuchman-Rosta, Celia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Etiquette, Language & Culture

Business etiquette, language & culture Page 1 of 5 Business etiquette, language & culture Overview Khmer is the official language of Cambodia and is used by roughly 90% of the population. Due to the past colonial rule by France, a number of French words exist in the language. However, English is not widely understood, particularly amongst the older generation and in rural areas. Business cards should be translated into Cambodian and printed in English on one side and Cambodian on the other. Use the services of a professional translator (rather than translating online) – a list of translators and interpreters has been prepared by the British Embassy Phnom Penh for the convenience of British Nationals who may require these services and assistance in Cambodia, at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cambodia-list-of-translators-and- interpreters. As in China, business cards should be given and received with both hands and studied carefully. This is particularly important when dealing with Cambodia’s ethnic Chinese minority, many of whom hold influential positions in the country’s business community. The Cambodian culture is conservative and hierarchical, and Theravada Buddhism is practiced by 95% of the population. Followers adhere to the concept of collectivism – the idea that the family, neighbourhood and society is more important than the wishes of the individual – and as in many Asian cultures the sense of ‘face’ is also considered paramount. Consequently you should avoid causing public embarrassment, not lose your temper in public and strive to maintain a sense of harmony. As a sign of respect for western customs, handshakes are the norm between men, but it is not uncommon to greet women with the “Sampeah” – the placing of palms together in a prayer-like position at chest level, with a slight bow of the head. -

The Continuing Presence of Victims of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Today's

Powerful remains: the continuing presence of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime in today’s Cambodia HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Helen Jarvis Permanent People’s Tribunal, UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme [email protected] Abstract The Khmer Rouge forbade the conduct of any funeral rites at the time of the death of the estimated two million people who perished during their rule (1975–79). Since then, however, memorials have been erected and commemorative cere monies performed, both public and private, especially at former execution sites, known widely as ‘the killing fields’. The physical remains themselves, as well as images of skulls and the haunting photographs of prisoners destined for execution, have come to serve as iconic representations of that tragic period in Cambodian history and have been deployed in contested interpretations of the regime and its overthrow. Key words: Cambodia, Khmer Rouge, memorialisation, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, dark tourism Introduction A photograph of a human skull, or of hundreds of skulls reverently arranged in a memorial, has become the iconic representation of Cambodia. Since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime on 7 January 1979, book covers, film posters, tourist brochures, maps and sign boards, as well as numerous original works of art, have featured such images of the remains of its victims, often coupled with the haunting term ‘the killing fields’, as well as ‘mug shots’ of prisoners destined for execution. Early examples on book covers include the first edition of Ben Kiernan’s seminal work How Pol Pot Came to Power, published in 1985, on which the map of Cambodia morphs into the shape of a human skull and Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death, edited by Karl D. -

Mission Statement

Mission Statement The Center for Khmer Studies promotes research, teaching and public service in the social sciences, arts and humanities in Cambodia and the Mekong region. CKS seeks to: • Promote research and international scholarly exchange by programs that increase understanding of Cambodia and its region, •Strengthen Cambodia’s cultural and educational struc- tures, and integrate Cambodian scholars in regional and inter- national exchange, • Promote a vigorous civil society. CKS is a private American Overseas Research Center support- ed by a consortium of educational institutions, scholars and individuals. It is incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA. It receives partial support for overhead and American fellowships from the US Government. Its pro- grams are privately funded. CKS is the sole member institution of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC) in Southeast Asia. CKS’s programs are administered from its headquarters in Siem Reap and from Phnom Penh. It maintains a small administrative office in New York and a support office in Paris, Les Three Generations of Scholars, Prof. SON Soubert (center), his teacher (left), and Board of Directors Amis du Centre Phon Kaseka (right) outside the Sre Ampil Museum d’Etudes Lois de Menil, Ph.D., President Khmeres. Anne H. Bass, Vice-President Olivier Bernier, Vice-President Center for Khmer Studies Dean Berry, Esq., Secretary and General Counsel Head Office: Gaye Fugate, Treasurer PO Box 9380 Wat Damnak, Siem Reap, Cambodia Prof. Michel Rethy Antelme, INALCO, Paris Tel: (855) 063 964 385 Prof. Kamaleswar Bhattacharya, Paris Fax: (855) 063 963 035 Robert Kessler, Denver, CO Phnom Penh Office: Emma C. -

![Annualreport [2002] IIAS Reasearch: Programmes, Networks and Fellowships [ Section 2 |P 27]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8707/annualreport-2002-iias-reasearch-programmes-networks-and-fellowships-section-2-p-27-478707.webp)

Annualreport [2002] IIAS Reasearch: Programmes, Networks and Fellowships [ Section 2 |P 27]

Annualreport [2002] IIAS Reasearch: Programmes, Networks and Fellowships [ section 2 |p 27] Senior visiting fellows Visiting exchange fellows The IIAS offers (senior) scholars the possibility to engage in research The IIAS has signed several Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) with work in the Netherlands. The period varies from one to three months. foreign research institutes, thereby providing scholars with an opportunity to participate in international exchanges for a maximum Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere (Sri Lanka) period of one year. Foreign scholars can apply to be sent abroad to the Stationed at the Branch Office Amsterdam MoU partners of the IIAS. Co-sponsored by the ISIM Period: 1 July–3 November 2002 Dr HO Ming-Yu (Taiwan) Topic: Restudying the veddah: Buddhism, aboriginality, and Co-sponsored by NSC. primitivism in pre-colonial and post-colonial discourses. Period: 18 December 2002 – 18 June 2003 Topic: Law, foreign direct investment, and economic development Academic activities: in Taiwan 1992-2002 24 September, ‘On quartering and cannibalism and forms of anthropophagy’, lecture presented, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Prof. LIN Wei-Sheng (Taiwan) Co-sponsored by NSC Period: 9 October – 15 March 2003 Topic: Transformation of international trade in Taiwan under Dutch rule Dr TSENG Mei-Chiun (Taiwan) Co-sponsored by NSC. Period: 1 December 2002 – 1 March 2003 Topic: Costs of first-ever eschemic stroke in Taiwan. Academic activities: Two abstracts prepared for the 12th European Stroke Conference were accepted for poster presentation. (poster-number Management/Economics 8, and Risk Factors and Etiology 32, respectively). Following the conference submission, we completed the full papers and submitted them to the Stroke journal (http://stroke.ahajournals.org/) for publication consideration (manuscript #03-0177 and #03-0204). -

Newcambodia 1 HS

CULTUREGUIDE CAMBODIA SERIES 1 SECONDARY (7–12) Photo by Florian Hahn on Unsplash CAMBODIA CULTUREGUIDE This unit is published by the International Outreach Program of the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies at Brigham Young University as part of an effort to foster open cultural exchange within the educational community and to promote increased global understanding by providing meaningful cultural education tools. Curriculum Development Richard Gilbert has studied the Cambodian language and culture since 1997. For two years, he lived among the Cambodian population in Oakland, California. He was later priv- ileged to work in Cambodia during the summer of 2001 as an intern for the U.S. Embassy. He is fluent in Cambodian and is a certified Cambodian language interpreter. Editorial Staff Content Review Committee Victoria Blanchard, CultureGuide publica- Jeff Ringer, director tions coordinator International Outreach Cory Leonard, assistant director Leticia Adams David M. Kennedy Center Adrianne Gardner Ana Loso, program coordinator Anvi Hoang International Outreach Anne Lowman Sopha Ly, area specialist Kimberly Miller Rebecca Thomas Special Thanks To: Julie Volmar Bradley Bessire, photographer Audrey Weight Kirsten Bodensteiner, photographer Andrew Gilbert, photographer J. Lee Simons, editor Brett Gilbert, photographer Kennedy Center Publications Ian Lowman, photographer: Monks and New Age Shaman in Phnom Penh, Coconut Vender in Phnom Penh, Pediment on Eleventh Century Buddhist Temple, and Endangered Wat Nokor in Kâmpóng Cham For more information on the International Outreach program at Brigham Young University, contact International Outreach, 273 Herald R. Clark Building, PO Box 24537, Provo, UT 84604- 9951, (801) 422-3040, [email protected]. © 2004 International Outreach, David M. -

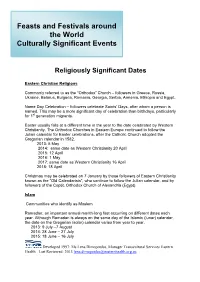

Feasts and Festivals Around the World Culturally Significant Events

Feasts and Festivals around the World Culturally Significant Events Religiously Significant Dates Eastern Christian Religions Commonly referred to as the “Orthodox” Church – followers in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia, Serbia, Armenia, Ethiopia and Egypt. Name Day Celebration – followers celebrate Saints’ Days, after whom a person is named. This may be a more significant day of celebration than birthdays, particularly for 1st generation migrants. Easter usually falls at a different time in the year to the date celebrated by Western Christianity. The Orthodox Churches in Eastern Europe continued to follow the Julian calendar for Easter celebrations, after the Catholic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582. 2013: 5 May 2014: same date as Western Christianity 20 April 2015: 12 April 2016: 1 May 2017: same date as Western Christianity 16 April 2018: 18 April Christmas may be celebrated on 7 January by those followers of Eastern Christianity known as the “Old Calendarists”, who continue to follow the Julian calendar, and by followers of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (Egypt). Islam Communities who identify as Moslem Ramadan: an important annual month-long fast occurring on different dates each year. Although Ramadan is always on the same day of the Islamic (lunar) calendar, the date on the Gregorian (solar) calendar varies from year to year. 2013: 9 July –7 August 2014: 28 June – 27 July 2015: 18 June – 16 July Developed 1997: Ms Lena Dimopoulos, Manager Transcultural Services Eastern Health Last Reviewed: 2013 [email protected] 2016: 6 June – 5 July 2017: 27 May – 25 July 2018: 16 May – 14 June New Year: some Moslems may fast during daylight hours. -

Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture

Thesis Title: Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture In fulfilment of the requirements of Master’s in Theology (Missiology) Submitted by: Gerard G. Ravasco Supervised by: Dr. Bill Domeris, Ph D March, 2004 Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The world we live in 1 1.2 The particular world we live in 1 1.3 Our target location: Cambodia 2 1.4 Our Particular Challenge: Cambodian Culture 2 1.5 An Invitation to Inculturation 3 1.6 My Personal Context 4 1.6.1 My Objectives 4 1.6.2 My Limitations 5 1.6.3 My Methodology 5 Chapter 2 2.0 Religious Influences in Early Cambodian History 6 2.1 The Beginnings of a People 6 2.2 Early Cambodian Kingdoms 7 2.3 Funan 8 2.4 Zhen-la 10 2.5 The Founding of Angkor 12 2.6 Angkorean Kingship 15 2.7 Theravada Buddhism and the Post Angkorean Crisis 18 2.8 An Overview of Christianity 19 2.9 Conclusion 20 Chapter 3 3.0 Religions that influenced Cambodian Culture 22 3.1 Animism 22 3.1.1 Animism as a Philosophical Theory 22 3.1.2 Animism as an Anthropological Theory 23 3.1.2.1 Tylor’s Theory 23 3.1.2.2 Counter Theories 24 3.1.2.3 An Animistic World View 24 3.1.2.4 Ancestor Veneration 25 3.1.2.5 Shamanism 26 3.1.3 Animism in Cambodian Culture 27 3.1.3.1 Spirits reside with us 27 3.1.3.2 Spirits intervene in daily life 28 3.1.3.3 Spirit’s power outside Cambodia 29 3.2 Brahmanism 30 3.2.1 Brahmanism and Hinduism 30 3.2.2 Brahmin Texts 31 3.2.3 Early Brahmanism or Vedism 32 3.2.4 Popular Brahmanism 33 3.2.5 Pantheistic Brahmanism -

Caring for the Dead Ritually in Cambodia

Caring for the Dead Ritually in Cambodia John Cliff ord Holt* Buddhist conceptions of the after-life, and prescribed rites in relation to the dead, were modified adaptations of brahmanical patterns of religious culture in ancient India. In this article, I demonstrate how Buddhist conceptions, rites and dispositions have been sustained and transformed in a contemporary annual ritual of rising importance in Cambodia, pchum ben. I analyze phcum ben to determine its funda- mental importance to the sustenance and coherence of the Khmer family and national identity. Pchum ben is a 15-day ritual celebrated toward the end of the three-month monastic rain retreat season each year. During these 15 days, Bud- dhist laity attend ritually to the dead, providing special care for their immediately departed kin and other more recently deceased ancestors. The basic aim of pchum ben involves making a successful transaction of karma transfer to one’s dead kin, in order to help assuage their experiences of suffering. The proximate catalyst for pchum ben’s current popularity is recent social and political history in Southeast Asia, especially the traumatic events that occurred nationally in Cambodia during the early 1970s through the 1980s when the country experienced a series of convul- sions. Transformations in religious culture often stand in reflexive relationship to social and political change. Keywords: Cambodia, buddhism, Khmer Rouge, death, ritual, pchum ben, family, national identity Death is an inevitable fact of life. For the religious, its occurrence does not necessarily signal life’s end, but rather the beginning of a rite de passage, a transitional experience in which the newly dead leave behind the familiarity of human life for yet another mode of being beyond. -

Tuchman-Rosta Completedissertation Final

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Performance, Practice, and Possibility: How Large Scale Processes Affect the Bodily Economy of Cambodia’s Classical Dancers A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta March 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sally Ness, Chairperson Dr. Yolanda Moses Dr. Christina Schwenkel Dr. Deborah Wong Copyright by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta 2018 The Dissertation of Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of many inspiring individuals who have taken the time to guide my research and writing in small and large ways and across countries and oceans. To start, I thank Sophiline Cheam Shapiro and John Shapiro, co-founders of Khmer Arts, and Michael Sullivan the former director (and his predecessor Philippe Peycam) at the Center For Khmer Studies who provided the formal letters of affiliation required for me to begin my long-term research in Cambodia. Without them this research would not exist. I also thank all of the individuals who provided access to their organizations without whom I would not have been able to attain the full breadth of data collected: Fred Frumberg and Kang Rithisal at Amrita, Neak Kru Vong Metry at Apsara Art Association, Arn Chorn-Pond and Phloeun Prim at Cambodian Living Arts (and Ieng Sithul and Nop Thyda at the Folk and Classical Dance Class), Horm Bunheng and Chhon Sophearith at the Cambodian Cultural Village, Mam Si Hak at Koulen Restaurant, Ravynn Karet-Coxin at the Preah Ream Buppha Devi Conservatoire (NKF), Annie and Dei Lei at Smile of Angkor, Ouk Sothea at the School of Art, Siem Reap, Mann Kosal at Sovanna Phum, and Bun Thon at Temple Balcony Club. -

IN Focus 2011-2012 MICHAEL((Friday))Final Draft In

In Focus No.10, 2012-2013 No.10, The Center for Khmer Studies IN THIS ISSUE Welcome to CKS 3 KHMER DANCE PROJECT LOIS DE MENIL, PRESIDENT CKS TRAVEL Director’s Note 4-5 CKS Programs 16-19 MICHAEL SULLIVAN SUMMER JUNIOR RESIDENT FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM KHMER LANGUAGE AND CULTURE STUDY PROGRAM Members & Benefactors 6-7 SOUTHEAST ASIAN CURRICULUM DESIGN PROGRAM OLIVIER BERNIER, VICE-PRESIDENT PUBLISHING & TRANSLATION UPCOMING EVENTS The CKS Library 8-9 Feature Article 20-23 Activities & Projects 10-15 THE YASODHARAS̄RAMAŚ PROJECT CONFERENCES AND WORKSHOPS NATIONAL MUSEUM OF CAMBODIA DATABASE PROJECT Senior Fellows 24-27 OUTREACH ACTIVITIES AND LECTURE SERIES GIANT PUPPET PROJECT Photo: Detail of the caste over the entrance to the CKS Library depicting traditional Apsara dancers Mission Statement The Center for Khmer Studies supports research, teaching and public service in the social sciences, arts and humanities in Cambodia and the Mekong region. CKS seeks to: •Promote research and international scholarly exchange by programs that increase understanding of Cambodia and its region, •Strengthen Cambodia’s cultural and educational struc tures, and integrate Cambodian scholars into regional and international exchange, •Promote a vigorous civil society. CKS is an American Overseas Research Center supported by a consortium of educational institutions, scholars and individuals. It is incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA. It receives partial support for overhead and American fellowships from the US Government. Its programs are pri vately funded. CKS is the sole member institution of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC) in Southeast Asia. CKS’s programs are administered from its headquarters in Siem Reap and from Phnom Penh. -

German-Cambodian Relations

From the Cold War Legacy to a Cooperative Development Partnership Dr. Raimund Weiß www.kas.de/cambodia Mr. Robert Hör THE KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG Freedom, justice and solidarity are the basic principles underlying the work of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS). The KAS is a political foundation, closely associated with the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU). As co-founder of the CDU and the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967) united Christian-social, conserva- tive and liberal traditions. His name is synonymous with the democratic reconstruction of Germany, the firm alignment of foreign policy with the trans-Atlantic community of values, the vision of a unified Europe and an orientation towards the social market economy. His intellectual heritage continues to serve both as our aim as well as our obligation today. In our European and international cooperation efforts, we work for people to be able to live self-determined lives in freedom and dignity. We make a contribu- tion underpinned by values to helping Germany meet its growing responsibili- ties throughout the world. KAS has been working in Cambodia since 1994, striving to support the Cambodian people in fostering dialogue, building networks and enhancing scientific projects. Thereby, the foundation works towards creating an environment conducive to social and economic development. All programs are conceived and implemented in close cooperation with the Cambodian partners on central and sub-national level. © Copyright 2019 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Cambodia Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Cambodia House No 4, Street 462, Khan Chamkar Mon, P.O.Box 944, Phnom Penh, Kingdom of Cambodia, Telephone : +855 23 966 176 Email : Offi[email protected] Website : www.kas.de/cambodia Facebook : www.facebook.com/kaskambodscha www.kas.de/cambodiia FOREWORD This year we are celebrating 25 years of Konrad-Adenauer- As the current country representative of the Konrad- Stiftung in Cambodia. -

Choreopolitics and Disability in Contemporary Cambodian

Transforming the national body: choreopolitics and disability in contemporary Cambodian dance Abstract This paper analyses how dance traces geographies of nation and national identity. Focusing on contemporary dance in Cambodia, particularly in relation to disability, it examines how some dancers are shifting the constitution of the national ‘body’. The paper extends geographical exchanges with dance studies by drawing upon the concept of choreopolitics and analysing how it produces variegated enactments of nationality. In the process, the paper works across different approaches to the study of nations and extends our understanding of how the nation is a performed entity. Keywords: Cambodia, contemporary dance, disability, Epic Arts, geographies of performance, nationality Introduction This paper analyses how dance can reimagine the constitution and contours of the nation. Focusing on contemporary dance in Cambodia, it uses the concept of choreopolitics to investigate variegated enactments of nationality. Choreopolitics describes the relationship between kinetics and politicsi, but is concerned with the freedom to move and the ability to challenge existing bodily comportments through non-conformity. However, I suggest that choreopolitical expressions work across a dualism in geographical research whereby national identity is either located in material bodies or artefacts, or in affective domains that encompass, but exceed, these geographies.ii As 1 such, choreopolitics contributes to emerging research that connects different formations of national identity.iii The relationship between the nation and the performing arts encompasses imaginations and practices that are multiply inhabited, involving degrees of consensus and contestation, inclusion and exclusion. The performing arts expose such tensions through their content, form, creative choices, emotional entanglements, and relationship to the state, enabling researchers to ‘explore the paradoxes, ambiguities and complexities that surround nationality’iv.