UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Statement

Mission Statement The Center for Khmer Studies promotes research, teaching and public service in the social sciences, arts and humanities in Cambodia and the Mekong region. CKS seeks to: • Promote research and international scholarly exchange by programs that increase understanding of Cambodia and its region, •Strengthen Cambodia’s cultural and educational struc- tures, and integrate Cambodian scholars in regional and inter- national exchange, • Promote a vigorous civil society. CKS is a private American Overseas Research Center support- ed by a consortium of educational institutions, scholars and individuals. It is incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA. It receives partial support for overhead and American fellowships from the US Government. Its pro- grams are privately funded. CKS is the sole member institution of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC) in Southeast Asia. CKS’s programs are administered from its headquarters in Siem Reap and from Phnom Penh. It maintains a small administrative office in New York and a support office in Paris, Les Three Generations of Scholars, Prof. SON Soubert (center), his teacher (left), and Board of Directors Amis du Centre Phon Kaseka (right) outside the Sre Ampil Museum d’Etudes Lois de Menil, Ph.D., President Khmeres. Anne H. Bass, Vice-President Olivier Bernier, Vice-President Center for Khmer Studies Dean Berry, Esq., Secretary and General Counsel Head Office: Gaye Fugate, Treasurer PO Box 9380 Wat Damnak, Siem Reap, Cambodia Prof. Michel Rethy Antelme, INALCO, Paris Tel: (855) 063 964 385 Prof. Kamaleswar Bhattacharya, Paris Fax: (855) 063 963 035 Robert Kessler, Denver, CO Phnom Penh Office: Emma C. -

Carving out a Space for Alternative Voices Through Performing Arts in Contemporary Cambodian Tourism 77

Carving out a Space for Alternative Voices through Performing Arts in Contemporary Cambodian Tourism 77 Carving out a Space for Alternative Voices through Performing Arts in Contemporary Cambodian Tourism: Transformation, Transgression and Cambodia’s first gay classical dance company Saori HAGAI * Abstract This paper explores the potential for the global phenomenon of tourism to become a platform for performing art practitioners, dancers and artists to carve out a space for alternative voices through their performances and perhaps thereby to stimulate social transformation and even encourage evolutionary social transgression in Cambodia. Drawing on the post-colonial discourses of Geertz(1980)and Vickers(1989), this paper adopts tourism as a cultural arena which contributes to the deconstruction of the landscape of a country through the exposure to the wider global gaze. This is achieved by taking the case study of Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA in its calculated promotion of social transgression in the classical arts. Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA is the Cambodia’s first gay classical dance company(hereafter the Company)established in 2015, and sets a manifestation of their continuing commitment to social transformation through artistic dialogue both inside and outside of Cambodia. The increasing resonance of the LGBTQ movement across the world helped the Company to receive more global recognitions especially since the venerable TED Conference and other international art * Associate Professor, Ritsumeikan International, Ritsumeikan University 78 立命館大学人文科学研究所紀要(121号) foundations have chosen Ok as a recipient of various grants and fellowships. In this way the Company hopes to boost the maturity and quality of the dance discourse in a postmodern era that has greater space for airing alternative voices. -

Khmer Dance Project

KHMER DANCE PROJECT 1 KHMER DANCE PROJECT Royal Khmer Dance robam preah reachea trop Past and Present In 1906, two years after succeeding his half-brother Norodom, King Sisowath of Cambodia, accompanied by the Royal Ballet, embarked on a long trip to Marseilles for the French Colonial Exposition. France responded warmly to the charming dancers and the king’s entourage. The famous sculptor Rodin was so enchanted by the dancers that he traveled with them and drew evocative sketches of their fluid, graceful movements. Lamenting their inevitable departure, Rodin, profoundly moved, confessed: “What emptiness they left me with. I thought they had taken away the beauty of the world. I followed them to Marseilles; I would have followed them as far as Cairo.” Under the Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 1979, Royal Khmer dance was banned from the soil of Cambodia. Its artists were executed or died from malnutrition, illness and forced labor. After the regime's collapse in 1979, Royal Khmer dance had almost disappeared; few former dancers had survived. Ever since this brutal period, Royal Khmer dance has slowly 2 and painstakingly struggled to retrieve memories. Former dance masters have tried to revive the gestures, music, and artistry that are part of Khmer classical dance’s heritage. Their long-lasting and devoted efforts were finally recognized and honored when UNESCO proclaimed the Royal Ballet of Cambodia (or Royal Khmer dance) a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2003. Yet, two years later, the campus of Royal University of Fine Arts which is devoted to the Arts was moved out of the center of the capital Phnom Penh. -

Saint Mary's College School of Liberal Arts Department of Performing Arts

Saint Mary’s College School of Liberal Arts Department of Performing Arts Asian Dance Performing Arts PROFESSORS: Jia Wu OFFICE: LeFevre Theatre 5 OFFICE HOURS: by appointment only (T.TH 11:20 -12:50 pm) PHONE: (925) 631-4299 CLASS HOURS: 1:15-2:50 T TH COURSE DESCRIPTION: Classical dance is a significant symbol for the contemporary Asian nations-state and its diasporas. In this class, we will explore how the category of “classical dance” was defined in 20th and 21st century in Asia and investigate the performative value of the concept—that is, we will look into what the idea of “classical dance” does, how it is deployed, and examine the circumstances of its production and reception. Out of the many established classical and contemporary forms, our focus will be on,wayang wong and shadow puppet in Bali and Java, Kathak and Bharatanatyam in India, Peking Opera, Yangge, Ethnic Dances and “Revolution” Ballet in China and Classical Dance in Cambodia. We will explore the key sources upon which the dances are based; survey the histories of the forms that comprise the classical canon; and situate the revival, reconstruction, and institutionalization of classical dance as a symbol of national identity and heritage in these four nations. We will also look at “folk,” “social,” “popular,” “Bollywood,” “modern,” and “contemporary” dance as categories distinguished from—and which interrogate—classical structures. Throughout, we will critically consider the relationship between dance, colonialism, nationalism, religion, and social history. COURSE LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Dance in Bali and Java: students will be able to • Identify the basic characteristics and vocabulary in classical dance • Understand the key concepts and discourses involved in the study of these forms • Develop an awareness of the context and politics of performing as well as viewing these dances. -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

Dances Inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity a List Compiled by Alkis Raftis

Dances inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity A list compiled by Alkis Raftis www.CID-world.org/Cultural-Heritage/ The International Dance Council CID, being the official organization for dance, presents a list of dances recognized by UNESCO as part of the Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Dances are part of many customs or rituals included either in the Representative List or the Urgent Safeguarding List. I have listed below only cultural manifestations where dance is the central part. For information visit www.CID-world.org/Cultural-Heritage/ Send comments to the CID Secretariat or CID Sections in the respective countries. Representative List & Urgent Safeguarding List 2018 Yalli (Kochari, Tenzere), traditional group dances of Nakhchivan - Azerbaijan Khon, masked dance drama in Thailand - Thailand Mooba dance of the Lenje ethnic group of Central Province of Zambia - Zambia Mwinoghe, joyous dance - Malawi 2017 Zaouli, popular music and dance of the Guro communities in Côte d’Ivoire - Côte d'Ivoire Kushtdepdi rite of singing and dancing - Turkmenistan Kolo, traditional folk dance - Serbia Kochari, traditional group dance - Armenia Rebetiko – Greece Taskiwin, martial dance of the western High Atlas - Morocco 2016 Almezmar, drumming and dancing with sticks - Saudi Arabia Momoeria, New Year's celebration in eight villages of Kozani area, West Macedonia, Greece - Greece Music and dance of the merengue in the Dominican Republic - Dominican Republic Rumba in Cuba, a festive combination of music and dances and all -

Tuchman-Rosta, Celia

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performance, Practice, and Possibility: How Large-Scale Processes Affect the Bodily Economy of Cambodia's Classical Dancers Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qb8m3cx Author Tuchman-Rosta, Celia Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Performance, Practice, and Possibility: How Large Scale Processes Affect the Bodily Economy of Cambodia’s Classical Dancers A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta March 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sally Ness, Chairperson Dr. Yolanda Moses Dr. Christina Schwenkel Dr. Deborah Wong Copyright by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta 2018 The Dissertation of Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of many inspiring individuals who have taken the time to guide my research and writing in small and large ways and across countries and oceans. To start, I thank Sophiline Cheam Shapiro and John Shapiro, co-founders of Khmer Arts, and Michael Sullivan the former director (and his predecessor Philippe Peycam) at the Center For Khmer Studies who provided the formal letters of affiliation required for me -

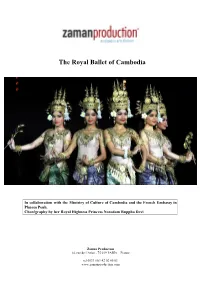

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia In collaboration with the Ministry of Culture of Cambodia and the French Embassy in Phnom Penh. Chorégraphy by her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Zaman Production 14, rue de l’Atlas - 75 019 PARIS – France tel 0033 (0)1 42 02 00 03 www.zamanproduction.com IMMATERIAL HERITAGE UNESCO duration : 1h20 UNESCO : Choreography by Her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Renowned for its graceful hand gestures and stunning costumes, the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, also known as Khmer Classical Dance, has been closely associated with the Khmer court for over one thousand years. Performances would traditionally accompany royal ceremonies and observances such as coronations, marriages, funerals or Khmer holidays. This art form, which narrowly escaped annihilation in the 1970s, is cherished by many Cambodians. Infused with a sacred and symbolic role, the dance embodies the traditional values of refinement, respect and spirituality. Its repertory perpetuates the legends associated with the origins of the Khmer people. Consequently, Cambodians have long esteemed this tradition as the emblem of Khmer culture. Four distinct character types exist in the classical repertory: Neang the woman, Neayrong the man, Yeak the giant, and Sva the monkey. Each possesses distinctive colours, costumes, makeup and masks.The gestures and poses, mastered by the dancers only after years of intensive training, evoke the gamut of human emotions, from fear and rage to love and joy. An orchestra accompanies the dance, and a female chorus provides a running commentary on the plot, highlighting the emotions mimed by the dancers, who were considered the kings’ messengers to the gods and to the ancestors. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

Tuchman-Rosta Completedissertation Final

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Performance, Practice, and Possibility: How Large Scale Processes Affect the Bodily Economy of Cambodia’s Classical Dancers A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta March 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sally Ness, Chairperson Dr. Yolanda Moses Dr. Christina Schwenkel Dr. Deborah Wong Copyright by Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta 2018 The Dissertation of Celia Johanna Tuchman-Rosta is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of many inspiring individuals who have taken the time to guide my research and writing in small and large ways and across countries and oceans. To start, I thank Sophiline Cheam Shapiro and John Shapiro, co-founders of Khmer Arts, and Michael Sullivan the former director (and his predecessor Philippe Peycam) at the Center For Khmer Studies who provided the formal letters of affiliation required for me to begin my long-term research in Cambodia. Without them this research would not exist. I also thank all of the individuals who provided access to their organizations without whom I would not have been able to attain the full breadth of data collected: Fred Frumberg and Kang Rithisal at Amrita, Neak Kru Vong Metry at Apsara Art Association, Arn Chorn-Pond and Phloeun Prim at Cambodian Living Arts (and Ieng Sithul and Nop Thyda at the Folk and Classical Dance Class), Horm Bunheng and Chhon Sophearith at the Cambodian Cultural Village, Mam Si Hak at Koulen Restaurant, Ravynn Karet-Coxin at the Preah Ream Buppha Devi Conservatoire (NKF), Annie and Dei Lei at Smile of Angkor, Ouk Sothea at the School of Art, Siem Reap, Mann Kosal at Sovanna Phum, and Bun Thon at Temple Balcony Club. -

Katalin Lőrincz, Ph. D. Cultural Tourism

Katalin Lőrincz, Ph. D. Cultural Tourism 1 H-8200 Veszprém, Egyetem u.10. H-8201 Veszprém, Pf. 158. Telefon: (+36 88) 624-000 Internet: www.uni-pannon.hu Cultural Tourism Author: Katalin Lőrincz, Ph.D. Proofreader: Sándor Czeglédi Publisher: University of Pannonia, Faculty of Business an Economics ISBN: 978-963-396-165-0 Készült az EFOP-3.4.3.-16-2016-00009 projekt keretében. Veszprém 2020 2 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................ 6 Cultural and Heritage Tourism .......................................................................................................... 6 Cultural and Heritage Tourism, and Why It Matters? ........................................................................... 6 The History of Cultural and Heritage tourism ....................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Cultural Tourism – Definitions and Different Approaches ............................................................. 9 Learning Outcomes ................................................................................................................................ 9 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 9 1.1. The Concept of Culture ................................................................................................................ -

IN Focus 2011-2012 MICHAEL((Friday))Final Draft In

In Focus No.10, 2012-2013 No.10, The Center for Khmer Studies IN THIS ISSUE Welcome to CKS 3 KHMER DANCE PROJECT LOIS DE MENIL, PRESIDENT CKS TRAVEL Director’s Note 4-5 CKS Programs 16-19 MICHAEL SULLIVAN SUMMER JUNIOR RESIDENT FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM KHMER LANGUAGE AND CULTURE STUDY PROGRAM Members & Benefactors 6-7 SOUTHEAST ASIAN CURRICULUM DESIGN PROGRAM OLIVIER BERNIER, VICE-PRESIDENT PUBLISHING & TRANSLATION UPCOMING EVENTS The CKS Library 8-9 Feature Article 20-23 Activities & Projects 10-15 THE YASODHARAS̄RAMAŚ PROJECT CONFERENCES AND WORKSHOPS NATIONAL MUSEUM OF CAMBODIA DATABASE PROJECT Senior Fellows 24-27 OUTREACH ACTIVITIES AND LECTURE SERIES GIANT PUPPET PROJECT Photo: Detail of the caste over the entrance to the CKS Library depicting traditional Apsara dancers Mission Statement The Center for Khmer Studies supports research, teaching and public service in the social sciences, arts and humanities in Cambodia and the Mekong region. CKS seeks to: •Promote research and international scholarly exchange by programs that increase understanding of Cambodia and its region, •Strengthen Cambodia’s cultural and educational struc tures, and integrate Cambodian scholars into regional and international exchange, •Promote a vigorous civil society. CKS is an American Overseas Research Center supported by a consortium of educational institutions, scholars and individuals. It is incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA. It receives partial support for overhead and American fellowships from the US Government. Its programs are pri vately funded. CKS is the sole member institution of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC) in Southeast Asia. CKS’s programs are administered from its headquarters in Siem Reap and from Phnom Penh.