Khmer Dance Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carving out a Space for Alternative Voices Through Performing Arts in Contemporary Cambodian Tourism 77

Carving out a Space for Alternative Voices through Performing Arts in Contemporary Cambodian Tourism 77 Carving out a Space for Alternative Voices through Performing Arts in Contemporary Cambodian Tourism: Transformation, Transgression and Cambodia’s first gay classical dance company Saori HAGAI * Abstract This paper explores the potential for the global phenomenon of tourism to become a platform for performing art practitioners, dancers and artists to carve out a space for alternative voices through their performances and perhaps thereby to stimulate social transformation and even encourage evolutionary social transgression in Cambodia. Drawing on the post-colonial discourses of Geertz(1980)and Vickers(1989), this paper adopts tourism as a cultural arena which contributes to the deconstruction of the landscape of a country through the exposure to the wider global gaze. This is achieved by taking the case study of Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA in its calculated promotion of social transgression in the classical arts. Prumsodun Ok & NATYARASA is the Cambodia’s first gay classical dance company(hereafter the Company)established in 2015, and sets a manifestation of their continuing commitment to social transformation through artistic dialogue both inside and outside of Cambodia. The increasing resonance of the LGBTQ movement across the world helped the Company to receive more global recognitions especially since the venerable TED Conference and other international art * Associate Professor, Ritsumeikan International, Ritsumeikan University 78 立命館大学人文科学研究所紀要(121号) foundations have chosen Ok as a recipient of various grants and fellowships. In this way the Company hopes to boost the maturity and quality of the dance discourse in a postmodern era that has greater space for airing alternative voices. -

Saint Mary's College School of Liberal Arts Department of Performing Arts

Saint Mary’s College School of Liberal Arts Department of Performing Arts Asian Dance Performing Arts PROFESSORS: Jia Wu OFFICE: LeFevre Theatre 5 OFFICE HOURS: by appointment only (T.TH 11:20 -12:50 pm) PHONE: (925) 631-4299 CLASS HOURS: 1:15-2:50 T TH COURSE DESCRIPTION: Classical dance is a significant symbol for the contemporary Asian nations-state and its diasporas. In this class, we will explore how the category of “classical dance” was defined in 20th and 21st century in Asia and investigate the performative value of the concept—that is, we will look into what the idea of “classical dance” does, how it is deployed, and examine the circumstances of its production and reception. Out of the many established classical and contemporary forms, our focus will be on,wayang wong and shadow puppet in Bali and Java, Kathak and Bharatanatyam in India, Peking Opera, Yangge, Ethnic Dances and “Revolution” Ballet in China and Classical Dance in Cambodia. We will explore the key sources upon which the dances are based; survey the histories of the forms that comprise the classical canon; and situate the revival, reconstruction, and institutionalization of classical dance as a symbol of national identity and heritage in these four nations. We will also look at “folk,” “social,” “popular,” “Bollywood,” “modern,” and “contemporary” dance as categories distinguished from—and which interrogate—classical structures. Throughout, we will critically consider the relationship between dance, colonialism, nationalism, religion, and social history. COURSE LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Dance in Bali and Java: students will be able to • Identify the basic characteristics and vocabulary in classical dance • Understand the key concepts and discourses involved in the study of these forms • Develop an awareness of the context and politics of performing as well as viewing these dances. -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

Dances Inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity a List Compiled by Alkis Raftis

Dances inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity A list compiled by Alkis Raftis www.CID-world.org/Cultural-Heritage/ The International Dance Council CID, being the official organization for dance, presents a list of dances recognized by UNESCO as part of the Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Dances are part of many customs or rituals included either in the Representative List or the Urgent Safeguarding List. I have listed below only cultural manifestations where dance is the central part. For information visit www.CID-world.org/Cultural-Heritage/ Send comments to the CID Secretariat or CID Sections in the respective countries. Representative List & Urgent Safeguarding List 2018 Yalli (Kochari, Tenzere), traditional group dances of Nakhchivan - Azerbaijan Khon, masked dance drama in Thailand - Thailand Mooba dance of the Lenje ethnic group of Central Province of Zambia - Zambia Mwinoghe, joyous dance - Malawi 2017 Zaouli, popular music and dance of the Guro communities in Côte d’Ivoire - Côte d'Ivoire Kushtdepdi rite of singing and dancing - Turkmenistan Kolo, traditional folk dance - Serbia Kochari, traditional group dance - Armenia Rebetiko – Greece Taskiwin, martial dance of the western High Atlas - Morocco 2016 Almezmar, drumming and dancing with sticks - Saudi Arabia Momoeria, New Year's celebration in eight villages of Kozani area, West Macedonia, Greece - Greece Music and dance of the merengue in the Dominican Republic - Dominican Republic Rumba in Cuba, a festive combination of music and dances and all -

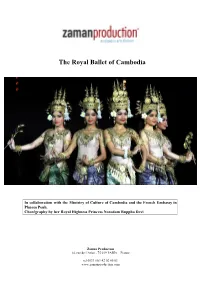

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia In collaboration with the Ministry of Culture of Cambodia and the French Embassy in Phnom Penh. Chorégraphy by her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Zaman Production 14, rue de l’Atlas - 75 019 PARIS – France tel 0033 (0)1 42 02 00 03 www.zamanproduction.com IMMATERIAL HERITAGE UNESCO duration : 1h20 UNESCO : Choreography by Her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Renowned for its graceful hand gestures and stunning costumes, the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, also known as Khmer Classical Dance, has been closely associated with the Khmer court for over one thousand years. Performances would traditionally accompany royal ceremonies and observances such as coronations, marriages, funerals or Khmer holidays. This art form, which narrowly escaped annihilation in the 1970s, is cherished by many Cambodians. Infused with a sacred and symbolic role, the dance embodies the traditional values of refinement, respect and spirituality. Its repertory perpetuates the legends associated with the origins of the Khmer people. Consequently, Cambodians have long esteemed this tradition as the emblem of Khmer culture. Four distinct character types exist in the classical repertory: Neang the woman, Neayrong the man, Yeak the giant, and Sva the monkey. Each possesses distinctive colours, costumes, makeup and masks.The gestures and poses, mastered by the dancers only after years of intensive training, evoke the gamut of human emotions, from fear and rage to love and joy. An orchestra accompanies the dance, and a female chorus provides a running commentary on the plot, highlighting the emotions mimed by the dancers, who were considered the kings’ messengers to the gods and to the ancestors. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

Katalin Lőrincz, Ph. D. Cultural Tourism

Katalin Lőrincz, Ph. D. Cultural Tourism 1 H-8200 Veszprém, Egyetem u.10. H-8201 Veszprém, Pf. 158. Telefon: (+36 88) 624-000 Internet: www.uni-pannon.hu Cultural Tourism Author: Katalin Lőrincz, Ph.D. Proofreader: Sándor Czeglédi Publisher: University of Pannonia, Faculty of Business an Economics ISBN: 978-963-396-165-0 Készült az EFOP-3.4.3.-16-2016-00009 projekt keretében. Veszprém 2020 2 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................ 6 Cultural and Heritage Tourism .......................................................................................................... 6 Cultural and Heritage Tourism, and Why It Matters? ........................................................................... 6 The History of Cultural and Heritage tourism ....................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Cultural Tourism – Definitions and Different Approaches ............................................................. 9 Learning Outcomes ................................................................................................................................ 9 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 9 1.1. The Concept of Culture ................................................................................................................ -

Milo Dinosaur: When Southeast Asia’S Cultural Heritage Meets Nestlé

ISSUE: 2019 No. 89 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore |24 October 2019 Milo Dinosaur: When Southeast Asia’s Cultural Heritage Meets Nestlé Geoffrey K. Pakiam, Gayathrii Nathan, and Toffa Abdul Wahed*1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Southeast Asia’s built heritage is already world-famous. Meanwhile, interest in the region’s intangible cultural heritage has been growing steadily. • As with built heritage, there are significant political, economic, and cultural sensitivities when elevating intangible cultural heritage through state channels within Southeast Asia. This is especially so in the case of food heritage. • Food heritage promotion has usually been associated with preserving traditional ‘homemade’ items from cultural homogenization and globalization processes. • There has been less attention paid to more recent forms of food heritage in Southeast Asia where multinational corporations influence the identity, ownership and commodification of food from the outset. • The growing popularity across Southeast Asia of the Milo Dinosaur beverage highlights this recent form and its inherent sensitivities. * Geoffrey K. Pakiam is Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute; email: [email protected]. He is the Principal Investigator for “Culinary Biographies: Singapore’s History Through Cooking and Consumption”, a project supported by the Heritage Research Grant of the National Heritage Board, Singapore. Gayathrii Nathan and Toffa Abdul Wahed are Research Assistants for the project. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 89 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION To the uninitiated, heritage can seem like antiquarian indulgence. Yet heritage pervades the present and helps shape the future of international relations, community identity, and economic development. Today, heritage officially encompasses not just old buildings but also intangible cultural heritage (ICH): long-standing ‘practices, representations, knowledge and skills’2 that often straddle borders, defy convenient categorization, and are easily commodified. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, 2009; 2010

2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Ircibrochure2017en2.Pdf

National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region IRCI 2017 National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) 2 cho, Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 590-0802, Japan Tel: +81-72-275-8050 Fax: +81-72-275-8151 http://www.irci.jp Contents IRCI and UNESCO IRCI and UNESCO Introduction of IRCI Greetings & Overview of IRCI ............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 UNESCO Category 2 Centres .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Operation of IRCI ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage ............................................................................................ 3 Introduction of IRCI What is Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH)? ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Activities of IRCI Greetings & Overview of IRCI Strategies and Projects -

Música Popular, Memória, Patrimônio

Poder e valor das listas nas políticas de patrimônio e na música popular Porto Alegre, 03 de maio de 2006 Texto elaborado para o debate A memória da música popular promovido pelo Projeto Unimúsica 2006 – festa e folguedo Elizabeth Travassos Instituto Villa-Lobos Programa de Pós-graduação em Música UNIRIO Gostaria de propor como contribuição a essa conversa sobre música popular uma reflexão sobre o fenômeno das listas; sobre o poder e o valor que têm as listas nas políticas de patrimônio e na canção popular. Como vocês sabem, listas e inventários adquiriram visibilidade, recentemente, a partir das proclamações pela UNESCO de “obras-primas do patrimônio cultural oral e imaterial da humanidade”. Segundo a Convenção aprovada na 32ª Assembléia Geral da UNESCO, em 2003, o patrimônio oral e imaterial abrange práticas, representações, conhecimentos e técnicas. Ele manifesta-se nas tradições e expressões orais, incluindo a língua, nos espetáculos, rituais e festas, nas técnicas do artesanato tradicional, em conhecimentos referentes à natureza. A Convenção nos propõe então olhar práticas sociais e festas como obras- primas. Este curto-circuito entre a noção antropológica de cultura, considerada como totalidade dos artefatos materiais e simbólicos do homem, e a noção altamente distintiva de obra-prima, causa certa perplexidade. Estaria incluída no patrimônio cultural a arte da conversação? Não admira que o tema se preste à controvérsia e mesmo ao humor. Foi em 2001 a primeira proclamação da UNESCO, que apontou 19 “obras- primas”, tais como a música de trompas transversas da comunidade Tagbana, na Costa do Marfim e o canto polifônico na República da Geórgia, entre muitas outras. -

The Inadequate Protection of Cultural Heritage in the United States, 15 J

THE JOHN MARSHALL REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW AMBER TEARS AND COPYRIGHT FEARS: THE INADEQUATE PROTECTION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE UNITED STATES INGRIDA R. LATOZA ABSTRACT The United States is comprised of many different cultural communities, each rich with expressions of language and custom. Cultural diversity promotes respect among individuals and harmonizes differences between communities—nationally and globally. Through the preservation of cultural heritage, diversity is maintained. Since World War II, with the exile of many from Lithuania, members of the Lithuanian-American community have strived to maintain the cultural heritage of their beloved homeland. After several decades, a Lithuanian-American cultural identity has developed, creating unique and individual traditions, adding to the cultural heritage of the United States as a whole. Most of the international community has adopted the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, but the United States relies on intellectual property laws, particularly the Copyright Act, to preserve cultural heritage. This comment explores the preservation of Lithuanian-American cultural heritage through the protection of copyright law with a modified standard for preserving and protecting intangible cultural heritage. Copyright © 2016 The John Marshall Law School Cite as Ingrida R. Latoza, Amber Tears and Copyright Fears: The Inadequate Protection of Cultural Heritage in the United States, 15 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 543 (2016). AMBER TEARS AND