Carving out a Space for Alternative Voices Through Performing Arts in Contemporary Cambodian Tourism 77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A N a K S a S T

A n a k S a s t r a Issue 20 Table of Contents s t o r i e s "Nasiruddin" by William Tham Wai Liang "Fingertips Pointing to the Sky" by Thomas De Angelo "Ma'af, Jam Berapa?" by Barry Rosenberg "Modern Love" by Lindsay Boyd n o n f i c t i o n "Kim and Seng Ly" by Hank Herreman p o e m s "Memories of Station One," "The Crossover to Miniloc Island," "Life Metaphors on the 6 a.m. Train," and "At the Corner of Maria Clara and Dimasalang" by Iris Orpi "Whispers in the Mist," "Monsoon Season in Thailand," and "Temple of Dawn" by Carl Wade Thompson "Not Defeated" by Clara Ray Rusinek Klein "A Tribute to My Own State of Collapse" by Abigail Bautista "Mourning" and "Hall of Mirrors" by Gerard Sarnat "Cakra Zen Warrior" by Gary Singh "Bony Carcass" and "Asking a Gas Station Clerk for Directions" by Pauline Lacanilao "Kata Hatiku" by James Penha "Here, There and Everywhere" and "A Felled Caress" by Lana Bella * * * * * Contributor Bios William Tham Wai Liang is currently a cherry analyst born in Kuala Lumpur but currently working in the Okanagan valley. He writes to pass the time and also to preserve any interesting stories that he comes across. Thomas De Angelo is an author in the United States with a particular interest in Southeast Asia. If any readers wish to comment on his story, he can be reached at ThomDeAngelo{at}aol.com. Barry Rosenberg was brought up in England but moved to Australia after completing a Ph.D. -

Khmer Dance Project

KHMER DANCE PROJECT 1 KHMER DANCE PROJECT Royal Khmer Dance robam preah reachea trop Past and Present In 1906, two years after succeeding his half-brother Norodom, King Sisowath of Cambodia, accompanied by the Royal Ballet, embarked on a long trip to Marseilles for the French Colonial Exposition. France responded warmly to the charming dancers and the king’s entourage. The famous sculptor Rodin was so enchanted by the dancers that he traveled with them and drew evocative sketches of their fluid, graceful movements. Lamenting their inevitable departure, Rodin, profoundly moved, confessed: “What emptiness they left me with. I thought they had taken away the beauty of the world. I followed them to Marseilles; I would have followed them as far as Cairo.” Under the Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 1979, Royal Khmer dance was banned from the soil of Cambodia. Its artists were executed or died from malnutrition, illness and forced labor. After the regime's collapse in 1979, Royal Khmer dance had almost disappeared; few former dancers had survived. Ever since this brutal period, Royal Khmer dance has slowly 2 and painstakingly struggled to retrieve memories. Former dance masters have tried to revive the gestures, music, and artistry that are part of Khmer classical dance’s heritage. Their long-lasting and devoted efforts were finally recognized and honored when UNESCO proclaimed the Royal Ballet of Cambodia (or Royal Khmer dance) a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2003. Yet, two years later, the campus of Royal University of Fine Arts which is devoted to the Arts was moved out of the center of the capital Phnom Penh. -

June 2020 #211

Click here to kill the Virus...the Italian way INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Table of Contents 1 Notams 2 Admin Reports 3-4-5 Covid19 Experience Flying the Line with Covid19 Paul Soderlind Scholarship Winners North Country Don King Atkins Stratocruiser Contributing Stories from the Members Bits and Pieces-June Gars’ Stories From here on out the If you use and depend on the most critical thing is NOT to RNPA Directory FLY THE AIRPLANE. you must keep your mailing address(es) up to date . The ONLY Instead, you MUST place that can be done is to send KEEP YOUR EMAIL UPTO DATE. it to: The only way we will have to The Keeper Of The Data Base: communicate directly with you Howie Leland as a group is through emails. Change yours here ONLY: [email protected] (239) 839-6198 Howie Leland 14541 Eagle Ridge Drive, [email protected] Ft. Myers, FL 33912 "Heard about the RNPA FORUM?" President Reports Gary Pisel HAPPY LOCKDOWN GREETINGS TO ALL MEMBERS Well the past few weeks and months have been a rude awakening for our past lifestyles. Vacations and cruises cancelled, all the major league sports cancelled, the airline industry reduced to the bare minimum. Luckily, I have not heard of many pilots or flight attendants contracting COVID19. Hopefully as we start to reopen the USA things will bounce back. The airlines at present are running at full capacity but with several restrictions. Now is the time to plan ahead. We have a RNPA cruise on Norwegian Cruise Lines next April. Things will be back to the new normal. -

Saint Mary's College School of Liberal Arts Department of Performing Arts

Saint Mary’s College School of Liberal Arts Department of Performing Arts Asian Dance Performing Arts PROFESSORS: Jia Wu OFFICE: LeFevre Theatre 5 OFFICE HOURS: by appointment only (T.TH 11:20 -12:50 pm) PHONE: (925) 631-4299 CLASS HOURS: 1:15-2:50 T TH COURSE DESCRIPTION: Classical dance is a significant symbol for the contemporary Asian nations-state and its diasporas. In this class, we will explore how the category of “classical dance” was defined in 20th and 21st century in Asia and investigate the performative value of the concept—that is, we will look into what the idea of “classical dance” does, how it is deployed, and examine the circumstances of its production and reception. Out of the many established classical and contemporary forms, our focus will be on,wayang wong and shadow puppet in Bali and Java, Kathak and Bharatanatyam in India, Peking Opera, Yangge, Ethnic Dances and “Revolution” Ballet in China and Classical Dance in Cambodia. We will explore the key sources upon which the dances are based; survey the histories of the forms that comprise the classical canon; and situate the revival, reconstruction, and institutionalization of classical dance as a symbol of national identity and heritage in these four nations. We will also look at “folk,” “social,” “popular,” “Bollywood,” “modern,” and “contemporary” dance as categories distinguished from—and which interrogate—classical structures. Throughout, we will critically consider the relationship between dance, colonialism, nationalism, religion, and social history. COURSE LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Dance in Bali and Java: students will be able to • Identify the basic characteristics and vocabulary in classical dance • Understand the key concepts and discourses involved in the study of these forms • Develop an awareness of the context and politics of performing as well as viewing these dances. -

Language and Culture of Cambodia SFS 2080

Language and Culture of Cambodia SFS 2080 Syllabus The School for Field Studies (SFS) Center for Conservation and Development Studies Siem Reap, Cambodia This syllabus may develop or change over time based on local conditions, learning opportunities, and faculty expertise. Course content may vary from semester to semester. www.fieldstudies.org © 2019 The School for Field Studies Fa19 COURSE CONTENT SUBJECT TO CHANGE Please note that this is a copy of a recent syllabus. A final syllabus will be provided to students on the first day of academic programming. SFS programs are different from other travel or study abroad programs. Each iteration of a program is unique and often cannot be implemented exactly as planned for a variety of reasons. There are factors which, although monitored closely, are beyond our control. For example: • Changes in access to or expiration or change in terms of permits to the highly regulated and sensitive environments in which we work; • Changes in social/political conditions or tenuous weather situations/natural disasters may require changes to sites or plans, often with little notice; • Some aspects of programs depend on the current faculty team as well as the goodwill and generosity of individuals, communities, and institutions which lend support. Please be advised that these or other variables may require changes before or during the program. Part of the SFS experience is adapting to changing conditions and overcoming the obstacles that may be present. In other words, the elephants are not always where we want them to be, so be flexible! 2 Course Overview The Language and Culture course contains two distinct but related modules: Cambodian society and culture, and Khmer language. -

Exploring Cambodian Classical Dance with Instructor: Sopheap Huot Editor: Claire Manigo-Bizzell Table of Contents

creating journeys through the arts Exploring Cambodian Classical Dance with Instructor: Sopheap Huot Editor: Claire Manigo-Bizzell Table of Contents i-iii Preface iv Glossary 1 Intro to Cambodian Classical Dance 2 Let’s Dance! The Neang Role Stretching Routine Part I 3 Let’s Dance! The Neang Role Stretching Routine Part II 4 Let’s Dance! The Neang Role Basic Gestures 5 Dance and Storytelling 6 Coloring Day: Learn about the Neang and Sva! 7 Coloring Day: Learn about the Neayrong and Yeak! 8 Reading Day: The Cambodian Dancer: Sophany’s Gift of Hope 9 Draw With Me: Masks in Cambodian Classical Dance 10 Let’s Explore! The Carvings at Angkor Wat 19 Appendix Art Sphere Inc • www.artsphere.org • [email protected] • © 2020 All Rights Reserved, Art Sphere Inc. Use this space to create your own art! Art Sphere Inc • www.artsphere.org • [email protected] • © 2020 All Rights Reserved, Art Sphere Inc. BOK Building, 1901 S 9th St. Studio 502, Philadelphia PA, 19148 • (215) 413 -3955 • www.artsphere.org• info@ artsphere.org creating journeys through the arts Follow your creativity and go beyond where the path leads so you can leave a trail to inspire others to express themselves, too! Preface How to Use Our Online Materials and We are pleased to present Creating Journeys This Book Through the Arts to take you on a path to Not everyone learns the same way. Some people transform everyday materials into art, to explore are more visual, some more musical, some more the intersections of art with nature, literacy, mathematical1. -

Namaste - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Namaste - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Namaste Namaste From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Namaste (/ˈnɑː məsteɪ/, Ⱦȱȸ -m əs-tay ; Sanskrit: नमते; Hindi: [n əməste ː]), sometimes expressed as Namaskar or Namaskaram , is a customary greeting when people meet or depart. [1][2] It is commonly found among Hindus of the Indian Subcontinent, in some Southeast Asian countries, and diaspora from these regions. [3][4] Namaste is spoken with a slight bow and hands pressed together, palms touching and fingers pointing upwards, thumbs close to the chest. This gesture is called Añjali Mudr ā or Pranamasana .[5] In Hinduism it means "I bow to the divine in you". [3][6] Namaste or namaskar is used as a respectful form of greeting, acknowledging and welcoming a relative, guest or stranger. It is used with goodbyes as well. It is typically spoken and simultaneously performed with the palms touching gesture, but it may also be spoken without acting it out or performed wordlessly; all three carry the same meaning. This cultural practice of salutation and valediction originated in the Indian A Mohiniattam dancer making a subcontinent.[7] Namaste gesture Contents 1 Etymology, meaning and origins 2 Uses 2.1 Regional variations 3 See also 4 References 5 External links Etymology, meaning and origins Namaste (Namas + te, Devanagari: नमः + ते = नमे) is derived from Sanskrit and is a combination of the word "Nama ḥa " and the enclitic 2nd person singular pronoun " te ".[8] The word " Nama ḥa " takes the Sandhi form "Namas " before the sound " t ".[9][10] Nama ḥa means 'bow', 'obeisance', 'reverential salutation' or 'adoration' [11] and te means 'to you' (dative case). -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

Dances Inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity a List Compiled by Alkis Raftis

Dances inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity A list compiled by Alkis Raftis www.CID-world.org/Cultural-Heritage/ The International Dance Council CID, being the official organization for dance, presents a list of dances recognized by UNESCO as part of the Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Dances are part of many customs or rituals included either in the Representative List or the Urgent Safeguarding List. I have listed below only cultural manifestations where dance is the central part. For information visit www.CID-world.org/Cultural-Heritage/ Send comments to the CID Secretariat or CID Sections in the respective countries. Representative List & Urgent Safeguarding List 2018 Yalli (Kochari, Tenzere), traditional group dances of Nakhchivan - Azerbaijan Khon, masked dance drama in Thailand - Thailand Mooba dance of the Lenje ethnic group of Central Province of Zambia - Zambia Mwinoghe, joyous dance - Malawi 2017 Zaouli, popular music and dance of the Guro communities in Côte d’Ivoire - Côte d'Ivoire Kushtdepdi rite of singing and dancing - Turkmenistan Kolo, traditional folk dance - Serbia Kochari, traditional group dance - Armenia Rebetiko – Greece Taskiwin, martial dance of the western High Atlas - Morocco 2016 Almezmar, drumming and dancing with sticks - Saudi Arabia Momoeria, New Year's celebration in eight villages of Kozani area, West Macedonia, Greece - Greece Music and dance of the merengue in the Dominican Republic - Dominican Republic Rumba in Cuba, a festive combination of music and dances and all -

Of Khmer Student Pre-Departure Handbook UNIVERSITY of HAWAI‘I at MĀNOA Department of Indo-Pacific Languages and Literatures Saklvitüal&Yhaévgiu ±±±

kmµviFIsiPßaPasaExµr SUMMER ABROAD PROGRAM Khmer Language and Culture 2019 advanced study of khmer Student Pre-Departure Handbook UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA Department of Indo-Pacific Languages and Literatures saklviTüal&yhaévGIu ±±± ± ± ±±± ± 1 2 Contact Information Table of Contents ±±± ±±± ¿ ASK Principle Investigator/Project Director Contact Information ............................................................................. 1 Dr. Chhany Sak-Humphry Email: [email protected] Welcome …………………………..................….........................………... 5 Websites: manoa.hawaii.edu/ask; khmer.hawaii.edu; www.hawaii.edu/khmer U.S. contact numbers Things You Need to be Aware of Office:(808) 956 8070 Conduct ®Illegal Activity ®Class Activities & Excursions ®Travel During Program 6 Cell: (808) 561 6850 Fax: (808) 956 5978 Things We Need From You Address & Contact Info ® Questions/Concerns ........................................... 7 University of Hawai'i at Ma ̄ noa ¿ Dept. of Indo-Pacific Languages & Literatures Academic Preparation 2540 Maile Way, Spalding Hall 255, Review Past Lessons ® Read & Listen to Recent Cambodian News ® Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822, U.S.A. Tel : (808) 956 8672 Earn University Credits .......................................................................... 8 Fax: (808) 956 5978 Website: manoa.hawaii.edu/ipll Tips for Safe Travel Important Documents .................................................................................... 9 ¿ Center for Khmer Studies Luggage Information ® Arrival in Phnom Penh ® Exiting Phnom -

Country Briefing Packet

INDONESIA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se INDONESIA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org INDONESIA Country Briefing Packet PRE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY? 5 The 10 Most Beautiful Places to Visit in Indonesia 5 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 8 BASIC STATISTICS 8 MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS 9 ADULT RISK FACTORS 9 TOP 10 CAUSES OF DEATH 10 BURDEN OF DISEASE 11 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 12 History 12 Geography 14 Climate and Weather 15 Demographics 16 Economy 18 Education 19 Religion 20 Culture 20 Poverty 22 SURVIVAL GUIDE 23 Etiquette 23 SAFETY 27 Currency 29 Money Changing - Inside Of Indonesia 30 IMR recommendations on money 31 TIME IN INDONESIA 32 EMBASSY INFORMATION 33 U. S. Embassy, Jakarta 33 U. S. Consulate General, Surabaya 33 WEBSITES 34 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org INDONESIA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the Indonesia Medical/Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The final section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. -

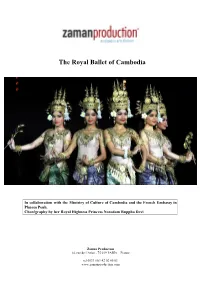

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia In collaboration with the Ministry of Culture of Cambodia and the French Embassy in Phnom Penh. Chorégraphy by her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Zaman Production 14, rue de l’Atlas - 75 019 PARIS – France tel 0033 (0)1 42 02 00 03 www.zamanproduction.com IMMATERIAL HERITAGE UNESCO duration : 1h20 UNESCO : Choreography by Her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Renowned for its graceful hand gestures and stunning costumes, the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, also known as Khmer Classical Dance, has been closely associated with the Khmer court for over one thousand years. Performances would traditionally accompany royal ceremonies and observances such as coronations, marriages, funerals or Khmer holidays. This art form, which narrowly escaped annihilation in the 1970s, is cherished by many Cambodians. Infused with a sacred and symbolic role, the dance embodies the traditional values of refinement, respect and spirituality. Its repertory perpetuates the legends associated with the origins of the Khmer people. Consequently, Cambodians have long esteemed this tradition as the emblem of Khmer culture. Four distinct character types exist in the classical repertory: Neang the woman, Neayrong the man, Yeak the giant, and Sva the monkey. Each possesses distinctive colours, costumes, makeup and masks.The gestures and poses, mastered by the dancers only after years of intensive training, evoke the gamut of human emotions, from fear and rage to love and joy. An orchestra accompanies the dance, and a female chorus provides a running commentary on the plot, highlighting the emotions mimed by the dancers, who were considered the kings’ messengers to the gods and to the ancestors.