CAMBODIA's SEARCH for JUSTICE Opportunities and Challenges For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

2 Nd Quarterly

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH Appeal for Donation of Archives Truth can Overcome Denial in Cambodia (Photo: Heng Chivoan) “DC-Cam appeals for the donation of archival material as part of its Special English Edition mission to provide Cambodians with greater access to their history Second Quarter 2013 by housing these archival collections within its facilities.” -- Youk Chhang Searching for the truth. Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia TABLE OF CONTENTS Special English Edition, Second Quarter 2013 LETTERS Appeal for Donation of Archives...........................1 Full of Hope with UNTAC....................................2 The Pandavas’ Journey Home................................3 DOCUMENTATION Hai Sam Ol Confessed...........................................6 HISTORY Sou Met, Former Khmer Rouge ...........................7 Tired of War, a Khmer Rouge Sodier...................9 From Khmer Rouge Militant to...........................12 Khmer Rouge Pedagogy......................................14 Chan Srey Mom: Prison looks.............................20 Malai: From Conflicted Area to...........................23 LEGAL Famine under the Khmer Rouge..........................26 Ung Pech was one of survivors from S-21 Security Office. In 1979, he turned Khieu Samphan to Remain..................................33 this Security Office into Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum with assistance from Vietnamese experts. Ung Pech had served as the director of this PUBLIC DEBATE museum until -

Historical Evidence at the ECCC

History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Andrew Mamo, History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC (May, 2013). Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10985172 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC Andrew Mamo The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) are marked by the amount of time that has elapsed between the fall of Democratic Kampuchea in 1979 and the creation of the tribunal. Does this passage of time matter? There are obvious practical reasons why it does: suspects die, witnesses die or have their memories fade, documents are lost and found, theories of accountability gain or lose currency within the broader public. And yet, formally, the mechanisms of criminal justice continue to operate despite the intervening years. The narrow jurisdiction limits the court’s attention to the events of 1975–1979, and potential evidence must meet legal requirements of relevance in order to be admissible. Beyond the immediate questions of the quality of the evidence, does history matter? Should it? One answer is that this history is largely irrelevant to the legal questions at issue. -

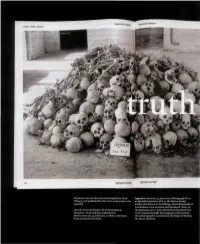

All Pieces Were Art-Directed and Designed by Youk Chhang, and Published by DC-Cam, Unless Otiierwise Specified. Spreads From

kuf All pieces were art-directed and designed by Youk Opposite: Issue no. 54, June Z004. Photograph of an Chhang, and published by DC-Cam, unless otiierwise unidentified prisoner of S-21, the Khmer Rouge specified. facility also known as Tuol Sleng, where thousands of Cambodians were tortured and murdered. Many of Spreads from Search ing for tbe Truth magazine. the prisoners at S-21 were themselves IiR cadres who Designers: Youk Chbang, Sophcak Sim. were arrested, brutally interrogated, and executed. Above: Issue no. 55, July 2004. A room at the Siem This photograph was printed in the hopes of finding Reap Genocide Memorial. the man's relatives. i ,«>**'«•". A CAMBODIAN DESIGNER ATTEMPTS TO MAKE PEACE WITH THE PAST BY ARCHIVING THE HORRORS OE THE KHMER ROUGE YEARS. By Edward Lovett nciliation In the late 1970s, Youk Chhang was living, archives the history of the Khmer Rouge as all Cambodians were, in the Khmer years. Since the victims cannot speak for Rouge's idea of Maoist agrarian Utopia. In themselves, Chhang has sought to unearth reality, his home was a slave labor camp rid- (often literally) and document a history that dled with famine and disease, ruled by an would otherwise remain unktiown. oppressive regime that was simultaneously In overseeing the design and production of paranoid, brutal, and inept. The prisoners in DC-Cam's publications, Chhang is also a the camp were forced to work the fields all graphic designer. But the content he presents day, every day. They were also critically is categorically different ftom that of most underfed, and they risked their lives to gath- designers. -

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia * Seeta Scully I. DEFINING A ―SUCCESSFUL‖ TRIBUNAL: THE DEBATE ...................... 302 A. The Human Rights Perspective ................................................ 303 B. The Social Perspective ............................................................. 306 C. Balancing Human Rights and Social Impacts .......................... 307 II. DEVELOPMENT & STRUCTURE OF THE ECCC ................................... 308 III. SHORTCOMINGS OF THE ECCC ......................................................... 321 A. Insufficient Legal Protections ................................................... 322 B. Limited Jurisdiction .................................................................. 323 C. Political Interference and Lack of Judicial Independence ....... 325 D. Bias ........................................................................................... 332 E. Corruption ................................................................................ 334 IV. SUCCESSES OF THE ECCC ................................................................ 338 A. Creation of a Common History ................................................ 338 B. Ending Impunity ....................................................................... 340 C. Capacity Building ..................................................................... 341 D. Instilling Faith in Domestic Institutions ................................... 342 E. Outreach .................................................................................. -

"The Collapse of Cambodian Democracy and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal"

TRANSCRIPT "The Collapse of Cambodian Democracy and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal" A conversation with Putsata Reang, Heather Ryan, and David Tolbert Moderator: Jim Goldston Recorded October 24, 2017 ANNOUNCER: You are listening to a recording of the Open Society Foundations, working to build vibrant and tolerant democracies worldwide. Visit us at OpenSocietyFoundations.org. JIM GOLDSTON: I'm Jim Goldston with the Open Society Justice Initiative, and we're very pleased to welcome you to this evening's-- (MIC NOISE) discussion on the collapse of Cambodian democracy and the Khmer Rouge tribunal. We have with us three great-- panelists who are gonna be looking at-- what has been happening in Cambodia and-- what has been the impact of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia-- in operation now for a decade. To my-- immediate right is David Tolbert, the president of the International Center for Transitional Justice, the former special expert to the U.N. secretary general on the E-triple-C, if I can call the Extraordinary Chambers that. And David brings, of course, a diverse range of experiences dealing with mass crimes in lots of places around the world. To his right is-- Putsata Reang, who is an author and journalist who's followed closely the work of the E-triple-C, and also broader developments-- in Cambodia. And to Putsata's right is Heather Ryan, a consultant with the Open Society Justice Initiative who has-- was based in Phnom Penh for quite some time, and has also monitored the court very, very closely. So we really have people who know what they're talking about, which is a good start for a great panel. -

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy Sophie Diamant Richardson Old Chatham, New York Bachelor of Arts, Oberlin College, 1992 Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia May, 2005 !, 11 !K::;=::: .' P I / j ;/"'" G 2 © Copyright by Sophie Diamant Richardson All Rights Reserved May 2005 3 ABSTRACT Most international relations scholarship concentrates exclusively on cooperation or aggression and dismisses non-conforming behavior as anomalous. Consequently, Chinese foreign policy towards small states is deemed either irrelevant or deviant. Yet an inquiry into the full range of choices available to policymakers shows that a particular set of beliefs – the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – determined options, thus demonstrating the validity of an alternative rationality that standard approaches cannot apprehend. In theoretical terms, a belief-based explanation suggests that international relations and individual states’ foreign policies are not necessarily determined by a uniformly offensive or defensive posture, and that states can pursue more peaceful security strategies than an “anarchic” system has previously allowed. “Security” is not the one-dimensional, militarized state of being most international relations theory implies. Rather, it is a highly subjective, experience-based construct, such that those with different experiences will pursue different means of trying to create their own security. By examining one detailed longitudinal case, which draws on extensive archival research in China, and three shorter cases, it is shown that Chinese foreign policy makers rarely pursued options outside the Five Principles. -

Culture & History Story of Cambodia

CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORY OF CAMBODIA FARINA SO, VANNARA ORN - DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA R KILLEAN, R HICKEY, L MOFFETT, D VIEJO-ROSE CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORYﺷﻤﺲ ISBN-13: 978-99950-60-28-2 OF CAMBODIA R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn - 1 - Documentation Center of Cambodia ζរចងាំ និង យុត្ិធម៌ Memory & Justice មជ䮈មណ䮌លឯក羶រកម្宻ᾶ DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA (DC-CAM) Villa No. 66, Preah Sihanouk Boulevard Phnom Penh, 12000 Cambodia Tel.: + 855 (23) 211-875 Fax.: + 855 (23) 210-358 E-mail: [email protected] CHAM CULTURE AND HISTORY STORY R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn 1. Cambodia—Law—Human Rights 2. Cambodia—Politics and Government 3. Cambodia—History Funding for this project was provided by the UK Arts & Humanities Research Council: ‘Restoring Cultural Property and Communities After Conflict’ (project reference AH/P007929/1). DC-Cam receives generous support from the US Agency for International Development (USAID). The views expressed in this book are the points of view of the authors only. Include here a copyright statement about the photos used in the booklet. The ones sent by Belfast were from Creative Commons, or were from the authors, except where indicated. Copyright © 2018 by R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose & the Documentation Center of Cambodia. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Hun Sen, the UN, and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Not Worth the Wait: Hun Sen, the UN, and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rh6566v Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 24(1) Author Bowman, Herbert D. Publication Date 2006 DOI 10.5070/P8241022188 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California NOT WORTH THE WAIT: HUN SEN, THE UN, AND THE KHMER ROUGE TRIBUNAL Herbert D. Bowman* I. INTRODUCTION Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge killed between one and three million Cambodians.1 Twenty-four years later, on March 17, 2003, the United Nations and the Cambodian govern- ment reached an agreement to establish a criminal tribunal de- signed to try those most responsible for the massive human rights violations which took place during the Khmer Rouge reign of terror. 2 Another three years later, on July 4, 2006, international and Cambodian judges and prosecutors were sworn in to begin work at the Extraordinary Chamber in the Courts of Cambodia ("ECCC"). 3 To quickly grasp the Cambodia court's prospects for success, one only need know a few basic facts. First, the jurisdiction of the court will be limited to crimes 4 that took place between April 17, 1975 and January 6, 1979. * Fellow of Indiana University School of Law, Indianapolis Center for Inter- national & Comparative Law. Former International Prosecutor for the United Na- tions Mission to East Timor. The author is currently working and living in Cambodia. 1. Craig Etcheson, The Politics of Genocide Justice in Cambodia, in INTERNA- TIONALIZED CRIMINAL COURTS: SIERRA LEONE, EAST TIMOR, Kosovo AND CAM- BODIA 181-82 (Cesare P.R. -

Bombs Over Cambodia

the walrus october 2006 History Bombs Over Cambodia New information reveals that Cambodia was bombed far more heavily during the Vietnam War than previously believed — and that the bombing began not under Richard Nixon, but under Lyndon Johnson story by Taylor Owen and Ben Kiernan mapping by Taylor Owen US Air Force bombers like this B-52, shown releasing its payload over Vietnam, helped make Cambodia one of the most heavily bombed countries in history — perhaps the most heavily bombed. In the fall of 2000, twenty-five years after the end of the war in Indochina, more ordnance on Cambodia than was previously believed: 2,756,941 Bill Clinton became the first US president since Richard Nixon to visit tons’ worth, dropped in 230,516 sorties on 113,716 sites. Just over 10 per- Vietnam. While media coverage of the trip was dominated by talk of cent of this bombing was indiscriminate, with 3,580 of the sites listed as some two thousand US soldiers still classified as missing in action, a having “unknown” targets and another 8,238 sites having no target listed small act of great historical importance went almost unnoticed. As a hu- at all. The database also shows that the bombing began four years earlier manitarian gesture, Clinton released extensive Air Force data on all Amer- than is widely believed — not under Nixon, but under Lyndon Johnson. ican bombings of Indochina between 1964 and 1975. Recorded using a The impact of this bombing, the subject of much debate for the past groundbreaking ibm-designed system, the database provided extensive three decades, is now clearer than ever. -

4 Th Quarterly

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH The Interpreter, The Translator, The Unknown Heroes Poch Younly’s Personal Accounts Photos: ECCC “Visitors to the Phnom Penh facility will learn the tragic legacy of Special English Edition the Khmer Rouge, remembering the victims as human beings Fourth Quarter 2013 unwittingly caught in the vortex of war, extremist ideology, and irrationality...” -- Zaha Hadid. Searching for the truth. Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia TABLE OF CONTENTS Special English Edition, Fourth Quarter 2013 LETTERS The Interpreter, The Translator..............................1 Zaha Hadid to Design the New..............................2 DOCUMENTATION Kuy Chea: The Front’s Ambassadorial Staff.........5 The Confession of Nuon Roeun.............................8 HISTORY It Was not Forced Evacuation..............................14 Khieu Samphan Make a Statment........................26 To Many, the Front Brings Them.........................28 Political Affairs Democratic ................................30 LEGAL Voice of Genocide................................................37 PUBLIC DEBATE Co-Presecutor: We Want to Live..........................50 FAMILY TRACING ECCC International co-prosecutor Nicolas Koumjian (Photo: DC-Cam) A Cross-Generation Reflection............................54 Copyright © Memory Remains beyond Khmer .......................57 My Father’s Life from 1975.................................59 Documentation Center of Cambodia All rights reserved. Licensed by the Ministry of Information of the Royal Government of Cambodia, Prakas No.0291 P.M99, 2 August 1999. Photographs by the Documentation Center of Cambodia and Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Contributors: Ty Lico, Nicolas Koumjian, Kallyann Kang, Randle C. DeFalco, Pechet Men, Dalin Lorn, Cheytoath Lim, Sreyneath Poole , Fatily Sa and Nikola Yann. Staff Writers: Bunthorn Som, Sarakmonin Teav and Sothida Sin Editor-in-chief: Socheat Nhean. English Editor: James Black. -

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 17 (October 2017), No. 194 Ben Kiernan, Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. xvi + 621 pp. Illustrations, maps, bibliography, and index. $34.95 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-0-1951-6076-5. Christopher Goscha, Vietnam: A New History. New York: Basic Books, 2016. xiv + 553 pp. Illustrations, maps, bibliography, and index. $35.00 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-0-4650-9436-3. K. W. Taylor, A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013. xv + 696 pp. Illustrations, maps, bibliography, and index. $49.99 U.S. (pb) ISBN 978-0-5216-9915-0. Review by Gerard Sasges, National University of Singapore. Those of us with an interest in the history of Vietnam should count ourselves lucky. In the space of just four years, three senior historians of Southeast Asia have produced comprehensive studies of Vietnam’s history. After long decades where available surveys all traced their origins to the Cold War, readers are now spoiled for choice with three highly detailed studies based on decades of research by some of the most renowned scholars in their fields: Ben Kiernan’s Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present, Christopher Goscha’s Vietnam: A New History, and Keith Taylor’s A History of the Vietnamese. Their appearance in such rapid succession reflects many things: the authors’ personal and professional trajectories, the continued interest of publics and publishers for books on Vietnamese history, and important changes in the field of Vietnamese Studies since the 1990s.