Historical Evidence at the ECCC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

2 Nd Quarterly

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH Appeal for Donation of Archives Truth can Overcome Denial in Cambodia (Photo: Heng Chivoan) “DC-Cam appeals for the donation of archival material as part of its Special English Edition mission to provide Cambodians with greater access to their history Second Quarter 2013 by housing these archival collections within its facilities.” -- Youk Chhang Searching for the truth. Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia TABLE OF CONTENTS Special English Edition, Second Quarter 2013 LETTERS Appeal for Donation of Archives...........................1 Full of Hope with UNTAC....................................2 The Pandavas’ Journey Home................................3 DOCUMENTATION Hai Sam Ol Confessed...........................................6 HISTORY Sou Met, Former Khmer Rouge ...........................7 Tired of War, a Khmer Rouge Sodier...................9 From Khmer Rouge Militant to...........................12 Khmer Rouge Pedagogy......................................14 Chan Srey Mom: Prison looks.............................20 Malai: From Conflicted Area to...........................23 LEGAL Famine under the Khmer Rouge..........................26 Ung Pech was one of survivors from S-21 Security Office. In 1979, he turned Khieu Samphan to Remain..................................33 this Security Office into Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum with assistance from Vietnamese experts. Ung Pech had served as the director of this PUBLIC DEBATE museum until -

All Pieces Were Art-Directed and Designed by Youk Chhang, and Published by DC-Cam, Unless Otiierwise Specified. Spreads From

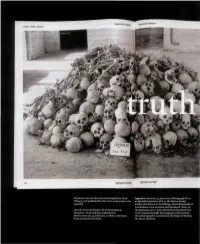

kuf All pieces were art-directed and designed by Youk Opposite: Issue no. 54, June Z004. Photograph of an Chhang, and published by DC-Cam, unless otiierwise unidentified prisoner of S-21, the Khmer Rouge specified. facility also known as Tuol Sleng, where thousands of Cambodians were tortured and murdered. Many of Spreads from Search ing for tbe Truth magazine. the prisoners at S-21 were themselves IiR cadres who Designers: Youk Chbang, Sophcak Sim. were arrested, brutally interrogated, and executed. Above: Issue no. 55, July 2004. A room at the Siem This photograph was printed in the hopes of finding Reap Genocide Memorial. the man's relatives. i ,«>**'«•". A CAMBODIAN DESIGNER ATTEMPTS TO MAKE PEACE WITH THE PAST BY ARCHIVING THE HORRORS OE THE KHMER ROUGE YEARS. By Edward Lovett nciliation In the late 1970s, Youk Chhang was living, archives the history of the Khmer Rouge as all Cambodians were, in the Khmer years. Since the victims cannot speak for Rouge's idea of Maoist agrarian Utopia. In themselves, Chhang has sought to unearth reality, his home was a slave labor camp rid- (often literally) and document a history that dled with famine and disease, ruled by an would otherwise remain unktiown. oppressive regime that was simultaneously In overseeing the design and production of paranoid, brutal, and inept. The prisoners in DC-Cam's publications, Chhang is also a the camp were forced to work the fields all graphic designer. But the content he presents day, every day. They were also critically is categorically different ftom that of most underfed, and they risked their lives to gath- designers. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia * Seeta Scully I. DEFINING A ―SUCCESSFUL‖ TRIBUNAL: THE DEBATE ...................... 302 A. The Human Rights Perspective ................................................ 303 B. The Social Perspective ............................................................. 306 C. Balancing Human Rights and Social Impacts .......................... 307 II. DEVELOPMENT & STRUCTURE OF THE ECCC ................................... 308 III. SHORTCOMINGS OF THE ECCC ......................................................... 321 A. Insufficient Legal Protections ................................................... 322 B. Limited Jurisdiction .................................................................. 323 C. Political Interference and Lack of Judicial Independence ....... 325 D. Bias ........................................................................................... 332 E. Corruption ................................................................................ 334 IV. SUCCESSES OF THE ECCC ................................................................ 338 A. Creation of a Common History ................................................ 338 B. Ending Impunity ....................................................................... 340 C. Capacity Building ..................................................................... 341 D. Instilling Faith in Domestic Institutions ................................... 342 E. Outreach .................................................................................. -

15.5 Analysis of Alternatives

EIA Report The Study on Dang Kor new disposal site development in Phnom Penh JICA Annex 15. Environment Impact Assessment Report KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. Figure 15-68: View of the new disposal site from Bakou (to North) 15.5 Analysis of Alternatives 15.5.1 Review of the Previous Report for Siting of Disposal Site Two studies on the selection of the candidate site for the new disposal site after closure of the Stung Mean Chey disposal site were conducted. One is the “Report on searching for new landfill” (DPWT No. 634, 11 August 1995) and the other is “Dump Site Construction” in Phnom Penh (April 1997). According to the minutes of meeting on the inception report of this study signed on the 10th of March 2003, the study team reviewed the above-mentioned studies to verify the appropriateness of the site where the MPP had already acquired 11 ha of land as a part of the proposed area based on the results of these studies. a. Review of “Report on searching for new landfill” (DPWT No.634, 11 August 1995) The following four candidate sites for the new disposal site were nominated for the study. Candidate 1: Prey Sala Village, Sangkat Kakoy, Khan Dang Kor Candidate 2: Sam Rong Village, Khan Dang Kor Candidate 3: Pray Speu Village, Khan Dang Kor Candidate 4: Choeung Ek Village, Sangkat Choeung Ek, Khan Dang Kor The characteristics are summarized in Table 15-60 and their locations are shown in. Figure 15-69. At the time of this study, it was presumed that an area of about 10 ha was to be considered as a candidate site. -

Download.Html; Zsombor Peter, Loss of Forest in Cambodia Among Worst in the World, Cambodia Daily, Nov

CAMBODIA LAW AND POLICY JOURNAL 2013-2014 CHY TERITH Editor-in-Chief, Khmer-language ANNE HEINDEL Editor-in-Chief, English-language CHARLES JACKSON SHANNON MAREE TORRENS Editorial Advisors LIM CHEYTOATH SOKVISAL KIMSROY Articles Editors, Khmer-language LIM CHEYTOATH SOPHEAK PHEANA SAY SOLYDA PECHET MEN Translators HEATHER ANDERSON RACHEL KILLEAN Articles Editor, English-language YOUK CHHANG, Director, Documentation Center of Cambodia JOHN CIORCIARI, Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, Michigan University RANDLE DEFALCO, Articling Student-at-Law at the Hamilton Crown Attorney’s Office, LL.M, University of Toronto JAYA RAMJI-NOGALES, Associate Professor, Temple University Beasley School of Law PEOUDARA VANTHAN, Deputy Director Documentation Center of Cambodia Advisory Board ISSN 2408-9540 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this journal are those of the authors only. Copyright © 2014 by the Documentation Center of Cambodia. All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Cambodia Law and PoLiCY JoURnaL Eternal (2013). Painting by Asasax The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) is pleased to an- design, which will house a museum, research center, and a graduate nounce Cambodia’s first bi-annual academic journal published in English studies program. The Cambodia Law and Policy Journal, part of the and Khmer: The Cambodia Law and Policy Journal (CLPJ). DC-Cam Center’s Witnessing Justice Project, will be the Institute’s core academic strongly believes that empowering Cambodians to make informed publication. -

Perspectives

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Choeung Ek and Local Genocide Memorials.1

Memory and Sovereignty in Post-1979 Cambodia: Choeung Ek and Local Genocide Memorials.1 Rachel Hughes University of Melbourne, Australia Introduction This chapter seeks to investigate the politics and symbolism of memorial sites in Cambodia that are dedicated to the victims of the Democratic Kampuchea or “Pol Pot” period of 1975-1979. These national and local-level memorials were built during the decade immediately following the 1979 toppling of Pol Pot, during which time the Cambodian state was known as the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK). I will concentrate especially on the Choeung Ek Center for Genocide Crimes, located in the semi-rural outskirts of Phnom Penh. The chapter also examines local-level genocide memorials2 found throughout Cambodia. These two types of memorial — the large, central, national-level memorial, and the smaller, local memorial — command significant popular attention in contemporary Cambodia. An analysis of these two memorial types offers insights into PRK national reconstruction and the contemporary place-based politics of memory around Cambodia’s traumatic past. The Choeung Ek Center for Genocide Crimes The Choeung Ek Center for Genocide Crimes,3 featuring the large Memorial Stupa, is located fifteen kilometers southwest of Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. The site lies just outside of the urban fringe in Dang Kao district, but falls within the jurisdiction of the municipal authority of Phnom Penh. The Choeung Ek site, originally a Chinese graveyard, operated from 1977 to the end of 1978 as a killing site and burial ground for thousands of victims of Pol Pot’s purges (Chandler 1999: 139-140). -

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Abstract This Article

The Memory of the Cambodian Genocide: The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Abstract This article examines the representation of the memory of the Cambodian genocide in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh. The museum is housed in the former Tuol Sleng prison, a detention and torture centre through which thousands of people passed before execution at the Choeung Ek killing field. From its opening in 1980, the museum was a stake in the ongoing conflict between the new Vietnamese- backed government and Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge guerrillas. Its focus on encouraging an emotional response from visitors, rather than on pedagogy, was part of the museum’s attempt to engender public sympathy for the regime. Furthermore, in order to absolve former Khmer Rouge members in government of blame, the museum sort to attribute responsibility for the atrocities of the period to a handful of ‘criminals’. The article traces the development of the museum and its exhibitions up to the present, commenting on what this public representation of the past reveals about the memory of the genocide and the changing political situation in Cambodia. The Tuol Sleng prison (also known by its codename S-21) was the largest centre for torture during the rule of the Cambodian Khmer Rouge (KR) between 1975 and 1979. Prisoners were interrogated at Tuol Sleng before being taken to the Choeung Ek killing field located fifteen kilometres southwest of Phnom Penh. Approximately 20,000 people are believed to have been executed and buried at this site.1 In the wake of the Vietnamese invasion in 1979, two photojournalists discovered Tuol Sleng. -

4 Th Quarterly

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH The Interpreter, The Translator, The Unknown Heroes Poch Younly’s Personal Accounts Photos: ECCC “Visitors to the Phnom Penh facility will learn the tragic legacy of Special English Edition the Khmer Rouge, remembering the victims as human beings Fourth Quarter 2013 unwittingly caught in the vortex of war, extremist ideology, and irrationality...” -- Zaha Hadid. Searching for the truth. Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia TABLE OF CONTENTS Special English Edition, Fourth Quarter 2013 LETTERS The Interpreter, The Translator..............................1 Zaha Hadid to Design the New..............................2 DOCUMENTATION Kuy Chea: The Front’s Ambassadorial Staff.........5 The Confession of Nuon Roeun.............................8 HISTORY It Was not Forced Evacuation..............................14 Khieu Samphan Make a Statment........................26 To Many, the Front Brings Them.........................28 Political Affairs Democratic ................................30 LEGAL Voice of Genocide................................................37 PUBLIC DEBATE Co-Presecutor: We Want to Live..........................50 FAMILY TRACING ECCC International co-prosecutor Nicolas Koumjian (Photo: DC-Cam) A Cross-Generation Reflection............................54 Copyright © Memory Remains beyond Khmer .......................57 My Father’s Life from 1975.................................59 Documentation Center of Cambodia All rights reserved. Licensed by the Ministry of Information of the Royal Government of Cambodia, Prakas No.0291 P.M99, 2 August 1999. Photographs by the Documentation Center of Cambodia and Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Contributors: Ty Lico, Nicolas Koumjian, Kallyann Kang, Randle C. DeFalco, Pechet Men, Dalin Lorn, Cheytoath Lim, Sreyneath Poole , Fatily Sa and Nikola Yann. Staff Writers: Bunthorn Som, Sarakmonin Teav and Sothida Sin Editor-in-chief: Socheat Nhean. English Editor: James Black. -

The Continuing Presence of Victims of the Khmer

Powerful remains: the continuing presence of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime in today’s Cambodia HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Helen Jarvis Permanent People’s Tribunal, UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme [email protected] Abstract The Khmer Rouge forbade the conduct of any funeral rites at the time of the death of the estimated two million people who perished during their rule (1975–79). Since then, however, memorials have been erected and commemorative cere monies performed, both public and private, especially at former execution sites, known widely as ‘the killing fields’. The physical remains themselves, as well as images of skulls and the haunting photographs of prisoners destined for execution, have come to serve as iconic representations of that tragic period in Cambodian history and have been deployed in contested interpretations of the regime and its overthrow. Key words: Cambodia, Khmer Rouge, memorialisation, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, dark tourism Introduction A photograph of a human skull, or of hundreds of skulls reverently arranged in a memorial, has become the iconic representation of Cambodia. Since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime on 7 January 1979, book covers, film posters, tourist brochures, maps and sign boards, as well as numerous original works of art, have featured such images of the remains of its victims, often coupled with the haunting term ‘the killing fields’, as well as ‘mug shots’ of prisoners destined for execution. Early examples on book covers include the first edition of Ben Kiernan’s seminal work How Pol Pot Came to Power, published in 1985, on which the map of Cambodia morphs into the shape of a human skull and Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death, edited by Karl D.