Download Printable Issue (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

2 Nd Quarterly

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH Appeal for Donation of Archives Truth can Overcome Denial in Cambodia (Photo: Heng Chivoan) “DC-Cam appeals for the donation of archival material as part of its Special English Edition mission to provide Cambodians with greater access to their history Second Quarter 2013 by housing these archival collections within its facilities.” -- Youk Chhang Searching for the truth. Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia TABLE OF CONTENTS Special English Edition, Second Quarter 2013 LETTERS Appeal for Donation of Archives...........................1 Full of Hope with UNTAC....................................2 The Pandavas’ Journey Home................................3 DOCUMENTATION Hai Sam Ol Confessed...........................................6 HISTORY Sou Met, Former Khmer Rouge ...........................7 Tired of War, a Khmer Rouge Sodier...................9 From Khmer Rouge Militant to...........................12 Khmer Rouge Pedagogy......................................14 Chan Srey Mom: Prison looks.............................20 Malai: From Conflicted Area to...........................23 LEGAL Famine under the Khmer Rouge..........................26 Ung Pech was one of survivors from S-21 Security Office. In 1979, he turned Khieu Samphan to Remain..................................33 this Security Office into Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum with assistance from Vietnamese experts. Ung Pech had served as the director of this PUBLIC DEBATE museum until -

Historical Evidence at the ECCC

History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Andrew Mamo, History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC (May, 2013). Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10985172 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC Andrew Mamo The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) are marked by the amount of time that has elapsed between the fall of Democratic Kampuchea in 1979 and the creation of the tribunal. Does this passage of time matter? There are obvious practical reasons why it does: suspects die, witnesses die or have their memories fade, documents are lost and found, theories of accountability gain or lose currency within the broader public. And yet, formally, the mechanisms of criminal justice continue to operate despite the intervening years. The narrow jurisdiction limits the court’s attention to the events of 1975–1979, and potential evidence must meet legal requirements of relevance in order to be admissible. Beyond the immediate questions of the quality of the evidence, does history matter? Should it? One answer is that this history is largely irrelevant to the legal questions at issue. -

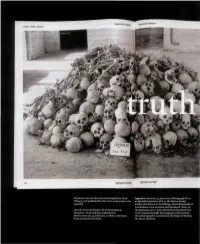

All Pieces Were Art-Directed and Designed by Youk Chhang, and Published by DC-Cam, Unless Otiierwise Specified. Spreads From

kuf All pieces were art-directed and designed by Youk Opposite: Issue no. 54, June Z004. Photograph of an Chhang, and published by DC-Cam, unless otiierwise unidentified prisoner of S-21, the Khmer Rouge specified. facility also known as Tuol Sleng, where thousands of Cambodians were tortured and murdered. Many of Spreads from Search ing for tbe Truth magazine. the prisoners at S-21 were themselves IiR cadres who Designers: Youk Chbang, Sophcak Sim. were arrested, brutally interrogated, and executed. Above: Issue no. 55, July 2004. A room at the Siem This photograph was printed in the hopes of finding Reap Genocide Memorial. the man's relatives. i ,«>**'«•". A CAMBODIAN DESIGNER ATTEMPTS TO MAKE PEACE WITH THE PAST BY ARCHIVING THE HORRORS OE THE KHMER ROUGE YEARS. By Edward Lovett nciliation In the late 1970s, Youk Chhang was living, archives the history of the Khmer Rouge as all Cambodians were, in the Khmer years. Since the victims cannot speak for Rouge's idea of Maoist agrarian Utopia. In themselves, Chhang has sought to unearth reality, his home was a slave labor camp rid- (often literally) and document a history that dled with famine and disease, ruled by an would otherwise remain unktiown. oppressive regime that was simultaneously In overseeing the design and production of paranoid, brutal, and inept. The prisoners in DC-Cam's publications, Chhang is also a the camp were forced to work the fields all graphic designer. But the content he presents day, every day. They were also critically is categorically different ftom that of most underfed, and they risked their lives to gath- designers. -

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia * Seeta Scully I. DEFINING A ―SUCCESSFUL‖ TRIBUNAL: THE DEBATE ...................... 302 A. The Human Rights Perspective ................................................ 303 B. The Social Perspective ............................................................. 306 C. Balancing Human Rights and Social Impacts .......................... 307 II. DEVELOPMENT & STRUCTURE OF THE ECCC ................................... 308 III. SHORTCOMINGS OF THE ECCC ......................................................... 321 A. Insufficient Legal Protections ................................................... 322 B. Limited Jurisdiction .................................................................. 323 C. Political Interference and Lack of Judicial Independence ....... 325 D. Bias ........................................................................................... 332 E. Corruption ................................................................................ 334 IV. SUCCESSES OF THE ECCC ................................................................ 338 A. Creation of a Common History ................................................ 338 B. Ending Impunity ....................................................................... 340 C. Capacity Building ..................................................................... 341 D. Instilling Faith in Domestic Institutions ................................... 342 E. Outreach .................................................................................. -

4 Th Quarterly

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH The Interpreter, The Translator, The Unknown Heroes Poch Younly’s Personal Accounts Photos: ECCC “Visitors to the Phnom Penh facility will learn the tragic legacy of Special English Edition the Khmer Rouge, remembering the victims as human beings Fourth Quarter 2013 unwittingly caught in the vortex of war, extremist ideology, and irrationality...” -- Zaha Hadid. Searching for the truth. Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia TABLE OF CONTENTS Special English Edition, Fourth Quarter 2013 LETTERS The Interpreter, The Translator..............................1 Zaha Hadid to Design the New..............................2 DOCUMENTATION Kuy Chea: The Front’s Ambassadorial Staff.........5 The Confession of Nuon Roeun.............................8 HISTORY It Was not Forced Evacuation..............................14 Khieu Samphan Make a Statment........................26 To Many, the Front Brings Them.........................28 Political Affairs Democratic ................................30 LEGAL Voice of Genocide................................................37 PUBLIC DEBATE Co-Presecutor: We Want to Live..........................50 FAMILY TRACING ECCC International co-prosecutor Nicolas Koumjian (Photo: DC-Cam) A Cross-Generation Reflection............................54 Copyright © Memory Remains beyond Khmer .......................57 My Father’s Life from 1975.................................59 Documentation Center of Cambodia All rights reserved. Licensed by the Ministry of Information of the Royal Government of Cambodia, Prakas No.0291 P.M99, 2 August 1999. Photographs by the Documentation Center of Cambodia and Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Contributors: Ty Lico, Nicolas Koumjian, Kallyann Kang, Randle C. DeFalco, Pechet Men, Dalin Lorn, Cheytoath Lim, Sreyneath Poole , Fatily Sa and Nikola Yann. Staff Writers: Bunthorn Som, Sarakmonin Teav and Sothida Sin Editor-in-chief: Socheat Nhean. English Editor: James Black. -

DOCUMENTATION CENTER of CAMBODIA YOUK CHHANG: STRATEGIC VISION for 2017-20 the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) Envisions a New Future for Cambodia

DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA YOUK CHHANG: STRATEGIC VISION FOR 2017-20 The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) envisions a new future for Cambodia. Cambodia has struggled for decades to come to grips with its past, not only on a personal and community level, but within its institutions—civil, cultural, and religious. Such transitions are never easy. Genocide and mass atrocities impact a society for generations. But post-conflict societies are not inevitably chained to their past. Proactive citizens can positively affect their circumstances, direction and future. Every new day brings new opportunities to mature and grow, but only if individuals, communities, and the nation are informed of and given the opportunity to discuss and reconcile themselves to their past. A country must deal with its past if it is to move forward. It is a struggle that is faced by every post-conflict society regardless of politics, culture, or circumstance. Indeed, to move forward, we must boldly research the past, commemorating human achievement, sacrifice, and resilience but also investigating and learning from humankind’s mistakes, failures, and evils. Despite decades of war, genocide, and suffering, Cambodia has not lost its spirit for life and it’s yearning for a better Cambodia will never escape its future. The struggle is not over. It has only just begun. Cambodia’s future will not only depend on our consideration of our past and present troubles, but also our courage to face the difficulties that liehead. a history, but it does not need to be Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives/Ouch Makara. -

Guidebook Teacher’S Guidebook the Teaching of “A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979)”

TEACHER’S GUIDEBOOK TEACHER’S GUIDEBOOK THE TEACHING OF “A HISTORY OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA (1975-1979)” The Documentation Center of Cambodia and the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport TEACHER’S GUIDEBOOK THE TEACHING OF “A HISTORY OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA (1975-1979)” Students receiving A History of Democratic Kampuchea textbooks at Youkunthor High School in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, October 2009. Photo by Terith Chy. Source: DC-Cam Archives. The Documentation Center of Cambodia and the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport Searching for the Truth: Memory & Justice Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) P.O. Box 1110, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tel.: +855 (23) 211-875 | Fax.: +855 (23) 210-358 Teacher’s Guidebook: The Teaching of “A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979)” Dr. Phala Chea and Chris Dearing Khmer Translation Team Dy Khamboly Pheng Pong Rasy Prak Keo Dara Editors (Khmer and English) Tep Meng Khean Youk Chhang Dacil Q. Keo Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport and DC-Cam’s Reviewers The rare Angkear-bos flower which Youk Chhang planted in 1967 at his primary school, Poeuv Um in Taul Alexander Hinton Ben Neang Beth Van Schaack Kauk, Phnom Penh. Photo by Chy Terith. Chea Kalyann Cheng Hong Chhim Dina Dacil Q. Keo David Chandler Frank Chalk George Chigas Gier Galle Foss Ieat Bun Leng Im Kouch Im Sethy Keo Dara Prak Copyright © 2009 by the Documentation Center of Cambodia and the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport. Kevin Murphy Khamboly Dy Kok-Thay Eng Kong Hak Leang Seng Hak Leng Sary All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or Ly Rumany Mao Veasna Meas Sokhan mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permis- Miriam Morgenstern Mom Meth Moung Sophat sion in writing from the publisher. -

CAMBODIA's SEARCH for JUSTICE Opportunities and Challenges For

CAMBODIA’S SEARCH FOR JUSTICE Opportunities and Challenges for the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia By Christine Malumphy and B.J. Pierce1 February 2009 Over 1.5 million people died as a result of the Khmer Rouge’s rise to power and subsequent rule. The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) represents an unprecedented opportunity in international jurisprudence for victims of crimes against humanity and genocide to participate actively in the trial of surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime. International observers and many Cambodians hope the trials will provide a measure of justice for the most serious crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to 1979. However, the Tribunal’s evolution and structure pose numerous challenges to the administration of justice. This paper reviews the development of the tribunal and identifies some of the barriers that must be overcome if the ECCC will achieve its mission. Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge Cambodia, seeking French protection from encroachments by Thailand and Vietnam, became a French protectorate in 1863.2 Almost a century later, in 1954, Cambodia 1 Interns, International Human Rights Law Clinic, University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. The authors prepared this paper under the supervision of Eric Stover, Faculty Director, Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley and Laurel E. Fletcher, Director, International Human Rights Law Clinic, University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. 2 GARY KLINTWORTH, VIETNAM’S INTERVENTION -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng &dss?e?73&£i& frjjrarijsfass cassis^ scesse & w o O as by Timothy Dylan Wood A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: y' 7* Stephen A. Tyler, Herbert S. Autrey Professor Department of Philip R. Wood, Professor Department of French Studies HOUSTON, TEXAS MAY 2009 UMI Number: 3362431 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3362431 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng by Timothy Dylan Wood Anlong Veng was the last stronghold of the Khmer Rouge until the organization's ultimate collapse and defeat in 1999. This dissertation argues that recent moves by the Cambodian government to transform this site into an "historical-tourist area" is overwhelmingly dominated by commercial priorities. However, the tourism project simultaneously effects an historical narrative that inherits but transforms the government's historiographic endeavors that immediately followed Democratic Kampuchea's 1979 ousting. -

6 Documenting the Crimes of Democratic Kampuchea

Article by John CIORCIARI and CHHANG Youk entitled "Documenting the Crimes of Democratic Kampuchea" in Jaya RAMJI and Beth VAN SCHAAK's book "Bringing the Khmer Rouge to Justice. Prosecuting Mass Violence Before the Cambodian Courts", pp.226-227. 6 Documenting The Crimes Of Democratic Kampuchea John D. Ciorciari with Youk Chhang John D. Ciorciari (A.B., J.D., Harvard; M.Phil., Oxford) is the Wai Seng Senior Research Scholar at the Asian Studies Centre in St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford. Since 1999, he has served as a legal advisor to the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) in Phnom Penh. Youk Chhang has served as the Director of DC-Cam since January 1997 and has managed the fieldwork of its Mass Grave Mapping Project since July 1995. He is also the Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of DC-Cam’s monthly magazine, SEARCHING FOR THE TRUTH, and has edited numerous scholarly publications dealing with the abuses of the Pol Pot regime. The Democratic Kampuchea (DK) regime was decidedly one of the most brutal in modern history. Between April 1975 and January 1979, when the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) held power in Phnom Penh, millions of Cambodians suffered grave human rights abuses. Films, museum exhibitions, scholarly works, and harrowing survivor accounts have illustrated the horrors of the DK period and brought worldwide infamy to the “Pol Pot regime.”1 Historically, it is beyond doubt that elements of the CPK were responsible for myriad criminal offenses. However, the perpetrators of the most serious crimes of that period have never been held accountable for their atrocities in an internationally recognized legal proceeding. -

Summer 2010 TO: Junsen A. Ohno, International Progra

Seattle University School of Law Cambodia Legal Internship Intern Report- Summer 2010 TO: Junsen A. Ohno, International Programs Administrator FROM: Krista Nelson, Summer Associate, Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) RE: Summer 2010 Documentation Center Report Dates of Internship Start: May 24, 2010 End: July 30, 2010 Supervisor: Anne Heindel, DC-Cam Legal Advisor Email: [email protected] Description of Internship Work Assignment: I. Legal Memorandum to the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) DC-Cam typically hires ten summer associates, all of whom are assigned a different legal issue to research for the ECCC. The topics vary and while most are procedural issues, there are often several substantive crimes to choose as a project. I researched the ECCC’s presumption of confidentiality during the pre-trial period, namely the presumption of confidential documents related to the judicial investigation and the presumption of in camera hearings before the Pre-Trial Chamber. While the ECCC’s internal rules of procedure explicitly enumerate confidentiality measures, so too do the rules mandate transparent proceedings when possible. Yet there are currently no standards to guide the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges and the Pre-Trial Chamber in their release of public information. Confidentiality measures at the ECCC have become a controversial topic recently, as the Ieng Sary Defence team was sanctioned for breaching the confidentiality of the judicial investigation when they posted information related to the case on their website; in addition, several journalists have been warned that reporting on material related to the investigation risks sanctions from the Court.