Conflicting Sites of Memory in Post-Genocide Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

Historical Evidence at the ECCC

History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Andrew Mamo, History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC (May, 2013). Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10985172 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA History and the Boundaries of Legality: Historical Evidence at the ECCC Andrew Mamo The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) are marked by the amount of time that has elapsed between the fall of Democratic Kampuchea in 1979 and the creation of the tribunal. Does this passage of time matter? There are obvious practical reasons why it does: suspects die, witnesses die or have their memories fade, documents are lost and found, theories of accountability gain or lose currency within the broader public. And yet, formally, the mechanisms of criminal justice continue to operate despite the intervening years. The narrow jurisdiction limits the court’s attention to the events of 1975–1979, and potential evidence must meet legal requirements of relevance in order to be admissible. Beyond the immediate questions of the quality of the evidence, does history matter? Should it? One answer is that this history is largely irrelevant to the legal questions at issue. -

First Quarterly Report: January-March, 2012

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia Quarterly Report: January‐March, 2012 DC‐Cam Team Leaders and the Management Team Prepared and Compiled by Farina So Office Manager Edited by Norman (Sambath) Pentelovitch April, 2012 Sirik Savina, Outreach Coordinator, discusses with the villagers about the hearing process at Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Abbreviations CHRAC Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee CP Civil Party CTM Cambodia Tribunal Monitor DC‐Cam Documentation Center of Cambodia DK Democratic Kampuchea ECCC Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia ICC International Criminal Court ITP Sida Advanced International Training Programme KID Khmer Institute for Democracy KR Khmer Rouge MMMF Margaret McNamara Memorial Fund MRDC Mondul Kiri Resource and Documentation Centre OCP Office of Co‐Prosecutors OCIJ Office of Co‐Investigating Judges PTSD Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Sida Swedish International Development Agency TSL Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum UN United Nations UNDP United Nation for Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VOT Victims of Torture VPA Victims Participation Project VSS Victim Support Section YFP Youth for Peace YRDP Youth Resource Development Program 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Results/Outcome................................................................................................................. 7 Raised Public Awareness on the Value of Documents............................................. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

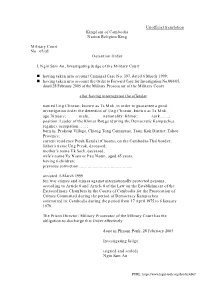

Ung Choeun, Known As Ta

Unofficial translation Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Military Court No 07/05 Detention Order I, Ngin Sam An, Investigating Judge of the Military Court n having taken into account Criminal Case No. 397, dated 6 March 1999; n having taken into account the Order to Forward Case for Investigation No.004/05, dated 28 February 2005 of the Military Prosecutor of the Military Court after having interrogated the offender named Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, in order to guarantee a good investigation order the detention of Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, age 78 years; male; nationality: Khmer; rank…….; position: Leader of the Khmer Rouge (during the Democratic Kampuchea regime); occupation……; born in Prakeap Village, Chieng Tong Commune, Tram Kok District, Takeo Province; current residence Pteah Kandal (Choam), on the Cambodia-Thai border; father’s name Ung Preak, deceased; mother’s name Uk Soch, deceased; wife’s name Vy Naen or Pau Naem, aged 45 years; having 6 children; previous conviction:………………………………… arrested: 6 March 1999 for: war crimes and crimes against internationally protected persons, according to Article 6 and Article 8 of the Law on the Establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for the Prosecution of Crimes Committed during the period of Democracy Kampuchea committed in: Cambodia during the period from 17 April 1975 to 6 January 1979. The Prison Director/Military Prosecutor of the Military Court has the obligation to discharge this Order effectively done in Phnom Penh, 28 February 2005 Investigating -

15.5 Analysis of Alternatives

EIA Report The Study on Dang Kor new disposal site development in Phnom Penh JICA Annex 15. Environment Impact Assessment Report KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. Figure 15-68: View of the new disposal site from Bakou (to North) 15.5 Analysis of Alternatives 15.5.1 Review of the Previous Report for Siting of Disposal Site Two studies on the selection of the candidate site for the new disposal site after closure of the Stung Mean Chey disposal site were conducted. One is the “Report on searching for new landfill” (DPWT No. 634, 11 August 1995) and the other is “Dump Site Construction” in Phnom Penh (April 1997). According to the minutes of meeting on the inception report of this study signed on the 10th of March 2003, the study team reviewed the above-mentioned studies to verify the appropriateness of the site where the MPP had already acquired 11 ha of land as a part of the proposed area based on the results of these studies. a. Review of “Report on searching for new landfill” (DPWT No.634, 11 August 1995) The following four candidate sites for the new disposal site were nominated for the study. Candidate 1: Prey Sala Village, Sangkat Kakoy, Khan Dang Kor Candidate 2: Sam Rong Village, Khan Dang Kor Candidate 3: Pray Speu Village, Khan Dang Kor Candidate 4: Choeung Ek Village, Sangkat Choeung Ek, Khan Dang Kor The characteristics are summarized in Table 15-60 and their locations are shown in. Figure 15-69. At the time of this study, it was presumed that an area of about 10 ha was to be considered as a candidate site. -

Download.Html; Zsombor Peter, Loss of Forest in Cambodia Among Worst in the World, Cambodia Daily, Nov

CAMBODIA LAW AND POLICY JOURNAL 2013-2014 CHY TERITH Editor-in-Chief, Khmer-language ANNE HEINDEL Editor-in-Chief, English-language CHARLES JACKSON SHANNON MAREE TORRENS Editorial Advisors LIM CHEYTOATH SOKVISAL KIMSROY Articles Editors, Khmer-language LIM CHEYTOATH SOPHEAK PHEANA SAY SOLYDA PECHET MEN Translators HEATHER ANDERSON RACHEL KILLEAN Articles Editor, English-language YOUK CHHANG, Director, Documentation Center of Cambodia JOHN CIORCIARI, Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, Michigan University RANDLE DEFALCO, Articling Student-at-Law at the Hamilton Crown Attorney’s Office, LL.M, University of Toronto JAYA RAMJI-NOGALES, Associate Professor, Temple University Beasley School of Law PEOUDARA VANTHAN, Deputy Director Documentation Center of Cambodia Advisory Board ISSN 2408-9540 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this journal are those of the authors only. Copyright © 2014 by the Documentation Center of Cambodia. All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Cambodia Law and PoLiCY JoURnaL Eternal (2013). Painting by Asasax The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) is pleased to an- design, which will house a museum, research center, and a graduate nounce Cambodia’s first bi-annual academic journal published in English studies program. The Cambodia Law and Policy Journal, part of the and Khmer: The Cambodia Law and Policy Journal (CLPJ). DC-Cam Center’s Witnessing Justice Project, will be the Institute’s core academic strongly believes that empowering Cambodians to make informed publication. -

Perspectives

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Choeung Ek and Local Genocide Memorials.1

Memory and Sovereignty in Post-1979 Cambodia: Choeung Ek and Local Genocide Memorials.1 Rachel Hughes University of Melbourne, Australia Introduction This chapter seeks to investigate the politics and symbolism of memorial sites in Cambodia that are dedicated to the victims of the Democratic Kampuchea or “Pol Pot” period of 1975-1979. These national and local-level memorials were built during the decade immediately following the 1979 toppling of Pol Pot, during which time the Cambodian state was known as the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK). I will concentrate especially on the Choeung Ek Center for Genocide Crimes, located in the semi-rural outskirts of Phnom Penh. The chapter also examines local-level genocide memorials2 found throughout Cambodia. These two types of memorial — the large, central, national-level memorial, and the smaller, local memorial — command significant popular attention in contemporary Cambodia. An analysis of these two memorial types offers insights into PRK national reconstruction and the contemporary place-based politics of memory around Cambodia’s traumatic past. The Choeung Ek Center for Genocide Crimes The Choeung Ek Center for Genocide Crimes,3 featuring the large Memorial Stupa, is located fifteen kilometers southwest of Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. The site lies just outside of the urban fringe in Dang Kao district, but falls within the jurisdiction of the municipal authority of Phnom Penh. The Choeung Ek site, originally a Chinese graveyard, operated from 1977 to the end of 1978 as a killing site and burial ground for thousands of victims of Pol Pot’s purges (Chandler 1999: 139-140). -

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Abstract This Article

The Memory of the Cambodian Genocide: The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Abstract This article examines the representation of the memory of the Cambodian genocide in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh. The museum is housed in the former Tuol Sleng prison, a detention and torture centre through which thousands of people passed before execution at the Choeung Ek killing field. From its opening in 1980, the museum was a stake in the ongoing conflict between the new Vietnamese- backed government and Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge guerrillas. Its focus on encouraging an emotional response from visitors, rather than on pedagogy, was part of the museum’s attempt to engender public sympathy for the regime. Furthermore, in order to absolve former Khmer Rouge members in government of blame, the museum sort to attribute responsibility for the atrocities of the period to a handful of ‘criminals’. The article traces the development of the museum and its exhibitions up to the present, commenting on what this public representation of the past reveals about the memory of the genocide and the changing political situation in Cambodia. The Tuol Sleng prison (also known by its codename S-21) was the largest centre for torture during the rule of the Cambodian Khmer Rouge (KR) between 1975 and 1979. Prisoners were interrogated at Tuol Sleng before being taken to the Choeung Ek killing field located fifteen kilometres southwest of Phnom Penh. Approximately 20,000 people are believed to have been executed and buried at this site.1 In the wake of the Vietnamese invasion in 1979, two photojournalists discovered Tuol Sleng. -

The Continuing Presence of Victims of the Khmer

Powerful remains: the continuing presence of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime in today’s Cambodia HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Helen Jarvis Permanent People’s Tribunal, UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme [email protected] Abstract The Khmer Rouge forbade the conduct of any funeral rites at the time of the death of the estimated two million people who perished during their rule (1975–79). Since then, however, memorials have been erected and commemorative cere monies performed, both public and private, especially at former execution sites, known widely as ‘the killing fields’. The physical remains themselves, as well as images of skulls and the haunting photographs of prisoners destined for execution, have come to serve as iconic representations of that tragic period in Cambodian history and have been deployed in contested interpretations of the regime and its overthrow. Key words: Cambodia, Khmer Rouge, memorialisation, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, dark tourism Introduction A photograph of a human skull, or of hundreds of skulls reverently arranged in a memorial, has become the iconic representation of Cambodia. Since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime on 7 January 1979, book covers, film posters, tourist brochures, maps and sign boards, as well as numerous original works of art, have featured such images of the remains of its victims, often coupled with the haunting term ‘the killing fields’, as well as ‘mug shots’ of prisoners destined for execution. Early examples on book covers include the first edition of Ben Kiernan’s seminal work How Pol Pot Came to Power, published in 1985, on which the map of Cambodia morphs into the shape of a human skull and Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death, edited by Karl D. -

“Please Don't Walk Through the Mass Grave”

“Please Don’t Walk Through The Mass Grave” Does this Message Reflect the Memorialization of the Cambodian Genocide? Max de Kruiff 10886230 June 2015 Supervisor: Nanci Adler Word Count: 22.910 Table of Contents Introduction 2 The Struggle of Politicized Memorialization 11 The Cambodian People and their Past: Memorializing 25 the Genocide from the Bottom Up Memorialization in Cambodia and the International Community 37 Conclusion 48 Bibliography 52 1 Introduction Fourteen kilometers southeast from the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh lies Choeung Ek. For those who do not wish to engage themselves in history, this site seems to be a calm part of the Cambodian rural landscape. A beautiful place, untouched by busy urban influences, Choeung Ek is Cambodia in its purest form. Sadly, Choeung Ek is an example of how something that seems so innocent at first sight is in fact a dark place which echoes the voices of death. Visiting Choeung Ek anno 2015 is a visit to one of history’s darkest pages. The well- preserved Killing Fields of Choeung Ek give a horrible and interesting peek in the terror of the Red Khmer regime at the same time. When entering the memorial site, the large stupa comes immediately into sight. Before reaching this building, the visitor is warned about the content of what will be seen at Choeung Ek. In the stupa, hundreds of skulls are shown to the visitor, a rather unpleasant but unfortunately realistic illustration of what happened there. I had the chance to visit Choeung Ek in 2011. The things that I experienced there and in Cambodia as a whole, inspired me to write this thesis.