1 Former Khmer Rouge Cadre Testifies on Evacuation Plans By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

First Quarterly Report: January-March, 2012

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia Quarterly Report: January‐March, 2012 DC‐Cam Team Leaders and the Management Team Prepared and Compiled by Farina So Office Manager Edited by Norman (Sambath) Pentelovitch April, 2012 Sirik Savina, Outreach Coordinator, discusses with the villagers about the hearing process at Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Abbreviations CHRAC Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee CP Civil Party CTM Cambodia Tribunal Monitor DC‐Cam Documentation Center of Cambodia DK Democratic Kampuchea ECCC Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia ICC International Criminal Court ITP Sida Advanced International Training Programme KID Khmer Institute for Democracy KR Khmer Rouge MMMF Margaret McNamara Memorial Fund MRDC Mondul Kiri Resource and Documentation Centre OCP Office of Co‐Prosecutors OCIJ Office of Co‐Investigating Judges PTSD Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Sida Swedish International Development Agency TSL Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum UN United Nations UNDP United Nation for Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VOT Victims of Torture VPA Victims Participation Project VSS Victim Support Section YFP Youth for Peace YRDP Youth Resource Development Program 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Results/Outcome................................................................................................................. 7 Raised Public Awareness on the Value of Documents............................................. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

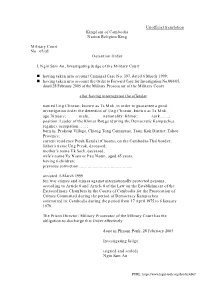

Ung Choeun, Known As Ta

Unofficial translation Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Military Court No 07/05 Detention Order I, Ngin Sam An, Investigating Judge of the Military Court n having taken into account Criminal Case No. 397, dated 6 March 1999; n having taken into account the Order to Forward Case for Investigation No.004/05, dated 28 February 2005 of the Military Prosecutor of the Military Court after having interrogated the offender named Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, in order to guarantee a good investigation order the detention of Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, age 78 years; male; nationality: Khmer; rank…….; position: Leader of the Khmer Rouge (during the Democratic Kampuchea regime); occupation……; born in Prakeap Village, Chieng Tong Commune, Tram Kok District, Takeo Province; current residence Pteah Kandal (Choam), on the Cambodia-Thai border; father’s name Ung Preak, deceased; mother’s name Uk Soch, deceased; wife’s name Vy Naen or Pau Naem, aged 45 years; having 6 children; previous conviction:………………………………… arrested: 6 March 1999 for: war crimes and crimes against internationally protected persons, according to Article 6 and Article 8 of the Law on the Establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for the Prosecution of Crimes Committed during the period of Democracy Kampuchea committed in: Cambodia during the period from 17 April 1975 to 6 January 1979. The Prison Director/Military Prosecutor of the Military Court has the obligation to discharge this Order effectively done in Phnom Penh, 28 February 2005 Investigating -

Conflicting Sites of Memory in Post-Genocide Cambodia

Brigitte Sion Conflicting Sites of Memory in Post-Genocide Cambodia A new road connects the towns of Siem Reap to Along Veng, in northern Cambodia; it now takes less then two hours from the temples of Angkor to reach the last bastion of the Khmer Rouge, in what used to be a dense jungle. It is enough time for my driver, thirty-one-year-old Vann, to tell me the story of his family. ‘‘Every Cambodian family has lost relatives under the Khmer Rouge,’’ he says. Vann’s mother lost her husband and children in the early years of Pol Pot’s murderous regime. She remarried and gave birth to a new set of children, including Vann. ‘‘A total of ten family members died,’’ he sums up. Later, when Vann was in school, he was required, along with all residents of his village outside Siem Reap, to excavate the killing fields and exhume the bodily remains for cremation. ‘‘The smell was horrible,’’ he recalls. ‘‘I see too many bones. It scares me.’’ For years, Vann avoided the former mass graves. ‘‘My children don’t know what happened.’’ A Khmer song is playing in the car. ‘‘Old music from the 1960s,’’ he says by means of introduction. ‘‘The singer was killed.’’ We pass Along Veng and continue through the lush countryside and rice fields toward the Thai border. It takes a number of stops and questions, and a few dollars, to find the cremation site of Pol Pot, who was burned hastily in 1998 on a pile of rubbish. It is hidden behind a house, amid high weeds, junk, and garbage. -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng &dss?e?73&£i& frjjrarijsfass cassis^ scesse & w o O as by Timothy Dylan Wood A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: y' 7* Stephen A. Tyler, Herbert S. Autrey Professor Department of Philip R. Wood, Professor Department of French Studies HOUSTON, TEXAS MAY 2009 UMI Number: 3362431 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3362431 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng by Timothy Dylan Wood Anlong Veng was the last stronghold of the Khmer Rouge until the organization's ultimate collapse and defeat in 1999. This dissertation argues that recent moves by the Cambodian government to transform this site into an "historical-tourist area" is overwhelmingly dominated by commercial priorities. However, the tourism project simultaneously effects an historical narrative that inherits but transforms the government's historiographic endeavors that immediately followed Democratic Kampuchea's 1979 ousting. -

6 Documenting the Crimes of Democratic Kampuchea

Article by John CIORCIARI and CHHANG Youk entitled "Documenting the Crimes of Democratic Kampuchea" in Jaya RAMJI and Beth VAN SCHAAK's book "Bringing the Khmer Rouge to Justice. Prosecuting Mass Violence Before the Cambodian Courts", pp.226-227. 6 Documenting The Crimes Of Democratic Kampuchea John D. Ciorciari with Youk Chhang John D. Ciorciari (A.B., J.D., Harvard; M.Phil., Oxford) is the Wai Seng Senior Research Scholar at the Asian Studies Centre in St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford. Since 1999, he has served as a legal advisor to the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) in Phnom Penh. Youk Chhang has served as the Director of DC-Cam since January 1997 and has managed the fieldwork of its Mass Grave Mapping Project since July 1995. He is also the Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of DC-Cam’s monthly magazine, SEARCHING FOR THE TRUTH, and has edited numerous scholarly publications dealing with the abuses of the Pol Pot regime. The Democratic Kampuchea (DK) regime was decidedly one of the most brutal in modern history. Between April 1975 and January 1979, when the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) held power in Phnom Penh, millions of Cambodians suffered grave human rights abuses. Films, museum exhibitions, scholarly works, and harrowing survivor accounts have illustrated the horrors of the DK period and brought worldwide infamy to the “Pol Pot regime.”1 Historically, it is beyond doubt that elements of the CPK were responsible for myriad criminal offenses. However, the perpetrators of the most serious crimes of that period have never been held accountable for their atrocities in an internationally recognized legal proceeding. -

07-31-12 CTM Blog Entry Trial

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne questions witness Rochoem Ton at the ECCC on Tuesday. Witness Rochoem Ton Faces Questions from the Bench and Defense Teams on Third Day of Testimony By Erica Embree, JD/LLM (International Human Rights) candidate, Class of 2015, Northwestern University School of Law Trial Chamber Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne and the defense teams for Nuon Chea and Ieng Sary took their turn examining witness Rochoem Ton on Tuesday, July 31, 2012, in Case 002 against accused Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan, and Ieng Sary at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). The morning proceedings were attended by 220 villagers from Kampot who left their village at 5 a.m. this morning in order to attend the proceedings. One hundred villagers from Kampong Som observed the afternoon proceedings. All parties were present in the courtroom, except Ieng Sary who continued to observe the proceedings via audio-visual equipment in his holding cell due to his health issues. Prior to giving the floor to the defense team for Nuon Chea, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn asked the members of the bench if anyone had questions to put to Rochoem Ton. Judge Lavergne indicated he wished to examine the witness and took the floor with several questions. Judge Lavergne Questions the Witness on Khieu Samphan Judge Lavergne first asked the witness about when he first met Khieu Samphan. The witness confirmed that he met Khieu Samphan in 1971, explaining that they met when Khieu Samphan went into the military kitchen hall, and they exchanged greetings. Judge Lavergne inquired whether the witness knew about or had discussions with any of the leadership about Khieu Samphan’s role, specifically his involvement in the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea (GRUNK). -

A Guide to the First Trial in Case 002 April 2014

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia A Guide to the First Trial in Case 002 April 2014 Introduction The second case before the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia is now on trial. In Case 002, four individuals who allegedly held high positions in the Khmer Rouge regime (Democratic Kampuchea) were charged with crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and genocide. Two of the four accused – former Deputy Sec- retary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea Nuon Chea and former Head of State Khieu xxxxxxxx Samphan – stand trial. The case against anoth- People waive white flags in the streets of Phnom Penh as the Khmer Rouge enter the city in er accused, Ieng Thirith, was severed after she April 1975 (Source: from the presentation of the prosecution’s opening statements) was found unfit to stand trial due to dementia while the proceedings against Ieng Sary were terminated after his death. Accused Persons The first trial in Case 002, known as Case 002/01, began on 21 November 2011 with opening statements by prosecutors and law- NUON Chea yers for civil parties and accused, and conclud- Date of Birth: 7 July 1926 ed with closing statements in late October Place of Birth: Voat Kor, Sangkae, Battambang 2013 following 20 months of evidentiary hear- Position in Democratic Kampuchea: Deputy Secretary of the ings. A trial judgement is expected in mid-2014. Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) Date of Arrest: 19 September 2007 The first trial focused on charges of crimes against humanity committed during the course Nuon Chea (Long Bunruot, by birth) studied law at Bangkok's Thammasat University, of two population movements, from Phnom where he became a member of the Thai Communist Party. -

Former Bodyguard and Messenger Provides Insight Into the Khmer

Khmer Rouge leaders during the struggle in the 1971. Nuon Chea is seated on the far left with Pol Pot seated third from the left. (Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia) Former Bodyguard and Messenger Provides Insight into the Khmer Rouge Leadership By Erica Embree, JD/LLM (International Human Rights) candidate, Class of 2015, Northwestern University School of Law The prosecution’s examination of witness Rochoem Ton continued Thursday, July 26, 2012, in Case 002 against accused Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan, and Ieng Sary at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were present in the courtroom. As usual, Ieng Sary participated remotely from his holding cell, as Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn had granted Ieng Sary’s request due to his health issues. National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Seng Bunkheang Continues His Examination of the Witness After President Nonn had called the court to order for the day, National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Seng Bunkheang continued his examination of the witness from yesterday. He returned to the questions by asking whether Pol Pot ever traveled to the front battlefield. Mr. Rochoem confirmed that Pol Pot did, adding that the leader would visit the places of Son Sen, Koy Thuon, and Ta Mok in Anlong Veng. Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea Son Arun interjected to request that the witness clarify the term “battlefield.” Mr. Bunkheang, after noting that it is “commonly used, a battlefield is a battlefield,” asked Mr. Rochoem to clarify. The witness replied that it is the place at which soldiers are trained and fight. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Intimate Enemies: Violence pologists and others working in post-confl ict and Reconciliation in Peru situations well beyond the Andes. The global Kimberley Theidon, 2013, Philadelphia: discourse of ‘trauma’ underlay the TRC’s work University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN: and informed psychological interventions in 9780812244502, 488 pp., Hb. £49.00. Ayacucho as it has in so many other parts of the world; Theidon brings it into juxtaposi- Reviewed by David Orr tion with her informants’ embodied idioms of health and affl iction, and the signifi cance In the 1980s and early 1990s, Peru was con- they placed on forgett ing. In doing so, she vulsed by confl ict between the Maoist revo- adds to the scholarly literature challenging lutionary group Shining Path and the armed the cross-cultural appropriateness of trauma. forces. Nearly 70,000 people died, while the She explores how communities found ways lives of many more were severely disrupted. to reincorporate the arrepentidos, or ‘repentant The ravages of those years have been am- terrorists’, through such means as the sign- ply documented by the country’s Truth and ing of actas (quasi-legal agreements/declara- Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a massive tions), the use of evangelical discourse around project drawing on thousands of testimonies forgiveness, or conceptual frameworks that from those most aff ected. Yet, as Theidon emphasized their ‘re-humanization’. Yet while argues, such a large-scale undertaking neces- the considerable achievements made through sarily tends to impose its own logic on the such forms of social reincorporation are high- accounts gathered and to eff ace more ‘experi- lighted, the narratives of many individuals ence-near’ meanings. -

F2/4/3/3/6/1/2 Before the Supreme Court Chamber

01154686 F2/4/3/3/6/1/2 BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT CHAMBER EXTRAORDINARY CHAMBERS IN THE COURTS OF CAMBODIA FILING DETAILS Case No: 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/SCC Party Filing: Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers Filed to: Supreme Court Chamber Original Language: English Date of Document: 16 October 2015 CLASSIFICA TION ORIGINAL/ORIGINAL ilJ is iJ (Date): ..~.~:9.~!:~~.~.~:.~~. :.~~. Classification of the document: PUBLIC CMS/CFO: •••••••••• ~~~~•• ~~.~.~ •••••••••• suggested by the filing party: MmmJl:/Public Classification by Chamber: Classification Status: Review of Interim Classification: Records Officer Name: Signature: CIVIL PARTY LEAD CO-LAWYERS' RESPONSE TO "NUON CHEA'S SUBMISSIONS ON ROBERT LEMKIN'S TRANSCRIPTS AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE 'RIFT' WITHIN THE CPK" Filed by: Before: Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers Supreme Court Chamber PICH Ang Judge KONG Srim, President Marie GUIRAUD Judge A. KLONOWIECKA-MILART Judge SOM Sereyvuth Judge C.N. JAY ASINGHE Co-Lawyers for Civil Parties Judge MONG Monichariya Judge Y A N arin CHET Vanly Judge Florence Ndepele MW ACHANDE HONG Kim Suon MUMBA KIM Mengkhy LOR Chunthy MOCH Sovannary Distribution to: SIN Sowom Office of the Co-Prosecutors SAM Sokong 01154687 F2/4/3/3/6/V2 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/SCC VEN Pov CHEA Leang TY Srinna Nicholas KOUMJIAN Philippe CANONNE Laure DESFORGES Ferdinand DJAMMEN NZEPA The Accused Elodie DULAC KHIEU Samphan Isabelle DURAND NUON Chea Franyoise GAUTRY Emmanuel JACOMY Martine JACQUIN Co-Lawyers for the Defence Yiqiang Y. LIU SON Arun Daniel LOSQ Victor KOPPE Christine MARTINEAU KONG Sam Onn LymaNGUYEN Anta GUISSE Mahesh RAI Arthur VERCKEN Nushin SARKARA TI Standby Counsel TOUCH Voleak Calvin SAUNDERS Co-Lawyers for Civil Parties Olivier BAHOUGNE Patrick BAUDOUIN Beini Ye 01154688 F2/4/3/3/6/V2 I.