Ian-Harris-Buddhist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

1 Post-Canonical Buddhist Political Thought

Post-Canonical Buddhist Political Thought: Explaining the Republican Transformation (D02) (conference draft; please do not quote without permission) Matthew J. Moore Associate Professor Dept. of Political Science Cal Poly State University 1 Grand Avenue San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 805-756-2895 [email protected] 1 Introduction In other recent work I have looked at whether normative political theorizing can be found in the texts of Early or Canonical Buddhism, especially the Nikāya collections and the Vinaya texts governing monastic life, since those texts are viewed as authentic and authoritative by all modern sects of Buddhism.1 In this paper I turn to investigate Buddhist normative political theorizing after the early or Canonical period, which (following Collins2 and Bechert3) I treat as beginning during the life of the Buddha (c. sixth-fifth centuries BCE) and ending in the first century BCE, when the Canonical texts were first written down. At first glance this task is impossibly large, as even by the end of the early period Buddhism had already divided into several sects and had begun to develop substantial regional differences. Over the next 2,000 years Buddhism divided into three main sects: Theravada, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna. It also developed into numerous local variants as it mixed with various national cultures and evolved under different historical circumstances. To give just one example, the Sri Lankan national epic, the Mahāvaṃsa, is central to Sinhalese Buddhists’ understanding of what Buddhism says about politics and very influential on other Southeast Asian versions of Buddhism, but has no obvious relevance to Buddhists in Tibet or Japan, who in turn have their own texts and traditions. -

Koh Kong Villagers Trade Logging for Agriculture

R 3464 E MB U N SSUE I TUESDAY, JULY 14, 2020 Intelligent . In-depth . Independent www.phnompenhpost.com 4000 RIEL Koh Kong villagers trade PHNOM PENH SQUATTERS GET logging for agriculture PLOTS OF LAND Khorn Savi used to live in mountainous areas, He said each family in the communi- incomes and fourth, they are safe. wildlife sanctuaries and natural re- ty had been granted land concessions “In the past, residents were no- TO RELOCATE VER 200 families living in source conservation areas along the measuring 25m by 600m to convert madic rice growers. They went to Koh Kong province’s Stung Prat canal and in the Chi Phat them into village lands and planta- clear forest land to grow rice and lat- NATIONAL – page 5 Sovanna Green Village area. tions. He said the plan was to give the er cleared forests in other places. This Community who used to In 2004, they moved to live at So- villagers new job opportunities. affected natural resources, biodiver- Olog timber and hunt wild animals for vanna Green Village, which is located “This project encourages changes to sity and other wild animals,” he said. a living have now turned to agricul- in Botum Sakor district’s Kandorl the livelihoods of residents and aims Pheaktra made the comments when ture to sustain themselves. commune. The village was an agri- to provide them with steady [jobs]. he led over 20 reporters to inspect Ministry of Environment spokes- cultural development project coordi- First, the lands belong to them. Sec- man Neth Pheaktra said the families nated by the Wildlife Alliance. -

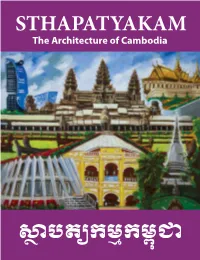

Sthapatyakam. the Architecture of Cambodia

STHAPATYAKAM The Architecture of Cambodia ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ The “Stha Patyakam” magazine team in front of Vann Molyvann’s French Library on the RUPP Campus Supervisor Dr. Tilman Baumgärtel Thanks to Yam Sokly, Heritage Mission, who has Design Supervisor Christine Schmutzler shared general knowledge about architecture in STHAPATYAKAM Editorial Assistant Jenny Nickisch Cambodia, Oun Phalline, Director of National Museum, The Architecture of Cambodia Writers and Editors An Danhsipo, Bo Sakalkitya, Sok Sophal, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Chey Phearon, Chhuon Sophorn, Cheng Bunlong, for an exclusive interview, Chheang Sidath, architect at Dareth Rosaline, Heng Guechly, Heang Sreychea, Ly Chhuong Import & Export Company, Nhem Sonimol, ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ Kun Chenda, Kim Kotara, Koeut Chantrea, Kong Sovan, architect student, who contributed the architecture Leng Len, Lim Meng Y, Muong Vandy, Mer Chanpolydet, books, Chhit Vongseyvisoth, architect student, A Plus Sreng Phearun, Rithy Lomor Pich, Rann Samnang, who contributed the Independence Monument picture, Samreth Meta, Soy Dolla, Sour Piset, Song Kimsour, Stefanie Irmer, director of Khmer Architecture Tours, Sam Chanmaliny, Ung Mengyean, Ven Sakol, Denis Schrey from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Phnom Department of Media and Communication Vorn Sokhan, Vann Chanvetey, Yar Ror Sartt, Penh for financial support of the printing, to the Royal University of Phnom Penh Yoeun Phary, Nou Uddom. Ministry of Tourism that has contributed the picture of Russian Boulevard, Phnom Penh Illustrator Lim -

Mission Statement

Mission Statement The Center for Khmer Studies promotes research, teaching and public service in the social sciences, arts and humanities in Cambodia and the Mekong region. CKS seeks to: • Promote research and international scholarly exchange by programs that increase understanding of Cambodia and its region, •Strengthen Cambodia’s cultural and educational struc- tures, and integrate Cambodian scholars in regional and inter- national exchange, • Promote a vigorous civil society. CKS is a private American Overseas Research Center support- ed by a consortium of educational institutions, scholars and individuals. It is incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA. It receives partial support for overhead and American fellowships from the US Government. Its pro- grams are privately funded. CKS is the sole member institution of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC) in Southeast Asia. CKS’s programs are administered from its headquarters in Siem Reap and from Phnom Penh. It maintains a small administrative office in New York and a support office in Paris, Les Three Generations of Scholars, Prof. SON Soubert (center), his teacher (left), and Board of Directors Amis du Centre Phon Kaseka (right) outside the Sre Ampil Museum d’Etudes Lois de Menil, Ph.D., President Khmeres. Anne H. Bass, Vice-President Olivier Bernier, Vice-President Center for Khmer Studies Dean Berry, Esq., Secretary and General Counsel Head Office: Gaye Fugate, Treasurer PO Box 9380 Wat Damnak, Siem Reap, Cambodia Prof. Michel Rethy Antelme, INALCO, Paris Tel: (855) 063 964 385 Prof. Kamaleswar Bhattacharya, Paris Fax: (855) 063 963 035 Robert Kessler, Denver, CO Phnom Penh Office: Emma C. -

100 May 2006

Published by the Cabinet of Samdech Hun Sen —————— MP of Kandal Prime Minister Issue 100 http://www.cnv.org.kh May 2006 22 and 26 May 2006 (Unofficial Translation of Selected Comments) 29 May 2006 (With Unofficial Translation of Selected Comments) Conferring the Rank of the Buddhist Patriarchs Affairs of Parliament, Senate & Inspection Building ..., I am greatly delighted to ticipation clearly reflects a preside over the inauguration sense of solidarity, unity and ceremony of the Ministry of high determination in con- Parliamentary Affairs and gratulating the new achieve- Inspection's Office Building, ment made by the Royal Gov- here at Tonle Basac district, ernment. Khan Chamkarmon, Phnom Penh, which is being held with In this joyful gathering, on the participation from Your behalf of the Royal Govern- Venerable Buddhist Monks, ment and myself, I would like Excellencies, Ladies and Gen- to express my brotherhood tlemen, Teachers, Students sentiment toward Your Vener- and my dear compatriots able Monks, Excellencies, whose participation make this Ladies and Gentlemen, Teach- occasion the most glorious Samdech Hun Sen and Madame Bun Rany Hun Sen at the Bathing and auspicious one. Your par- (Continued on page 3) Ceremony for the Great Supreme Patriarch—Samdech Tep Vong ... My wife and I, together through the Kingdom and 11 May 2006 (Unofficial Translation of Selected Comments) with officials and Buddhist about 60,000 Buddhist monks Graduation of Batches of Judges followers who are present here – a development that is be- have a great pleasure to join yond belief after the country Let me add further (to what I brought to court would be with all of our Buddhist recovered from the devasta- had to say in my prepared judged to be justice or injus- monks in giving a bath to tion under the genocide re- text). -

First Quarterly Report: January-March, 2012

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia Quarterly Report: January‐March, 2012 DC‐Cam Team Leaders and the Management Team Prepared and Compiled by Farina So Office Manager Edited by Norman (Sambath) Pentelovitch April, 2012 Sirik Savina, Outreach Coordinator, discusses with the villagers about the hearing process at Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Abbreviations CHRAC Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee CP Civil Party CTM Cambodia Tribunal Monitor DC‐Cam Documentation Center of Cambodia DK Democratic Kampuchea ECCC Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia ICC International Criminal Court ITP Sida Advanced International Training Programme KID Khmer Institute for Democracy KR Khmer Rouge MMMF Margaret McNamara Memorial Fund MRDC Mondul Kiri Resource and Documentation Centre OCP Office of Co‐Prosecutors OCIJ Office of Co‐Investigating Judges PTSD Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Sida Swedish International Development Agency TSL Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum UN United Nations UNDP United Nation for Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VOT Victims of Torture VPA Victims Participation Project VSS Victim Support Section YFP Youth for Peace YRDP Youth Resource Development Program 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Results/Outcome................................................................................................................. 7 Raised Public Awareness on the Value of Documents............................................. -

1 Engaged Buddhism East and West: Encounters with the Visions, Vitality, and Values of an Emerging Practice Paula Green The

Engaged Buddhism East and West: Encounters with the Visions, Vitality, and Values of an Emerging Practice Paula Green The latter decades of the 20th century witnessed the spread of Engaged Buddhism throughout Asia and the West, championed by Thich Nhat Hanh of Vietnam and building on earlier experiments especially in India and Sri Lanka. Based on wide interpretations of traditional Buddhist teachings, these new practices became tools of social change, creatively utilized by progressive monks, educators, reformers, environmentalists, medical doctors, researchers, activists, and peacebuilders. The experimental nature of a kind of sociopolitical and peace-oriented Dharma brought new followers to Buddhism in the West and revived Buddhist customs in the Asian lands of its birth and development. Traditionally inward and self-reflecting, Engaged Buddhism expanded Buddhist teaching to promote intergroup relations and societal structures that are inherently compassionate, just, and nonviolent. Its focus, embodied in the phrase, Peace Writ Large, signifies a greater magnitude and more robust agenda for peace than the absence of war. This chapter will focus on the emerging phenomenon of Engaged Buddhism East and West, looking at its traditional roots and contemporary branches, and discerning its impact on peacefulness, justice, tolerance, human and environmental rights, and related sociopolitical concerns. It will explore the organizational leadership and participation in engaged Buddhists processes, and what impact this movement has in both primarily Buddhist nations as well as in countries where Buddhists are a tiny minority and its practitioners may not have been born into Buddhist families. Traditional Buddhism and Social Engagement What is socially engaged Buddhism? For a religion that has traditionally focused on self- development and realization, its very designation indicates a dramatic departure. -

Re-Imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat During the People's Republic Of

Re-imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat during the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1989) Simon Bailey A Thesis in The Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2018 © Simon Bailey, 2018 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Simon Bailey Entitled: Re-imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat during the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1989) and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Chair Professor Barbara Lorenzkowski Examiner Professor. Theresa Ventura Examiner Professor Alison Rowley Supervisor Professor Matthew Penney Approved by Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director 2018 Dean of Faculty ABSTRACT Re-imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat during the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1989) Simon Bailey The People’s Republic of Kampuchea period between 1979 and 1989 is often overlooked when scholars work on the history of modern Cambodia. This decade is an academic blind spot sandwiched between the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime and the onset of the United Nations peace process. Utilizing mediums such as popular culture, postage stamps and performance art, this thesis will show how the single most identifiable image of Cambodian culture, Angkor Wat became a cultural binding agent for the government during the 1980s. To prove the centrality of Angkor in the myth-making and nation building mechanisms of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea, primary source material from Cambodia’s archives, along with interviews will form the foundation of this investigation. -

Part I Foundations of the Triple Gem: Buddha/S, Dharma/S, And

2 A Oneworld Book First published by Oneworld Publications, 2015 This eBook edition published 2015 Copyright © John S. Strong 2015 The moral right of John S. Strong to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78074-505-3 ISBN 978-1-78074-506-0 (eBook) Typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England 3 Contents List of Tables List of Figures Preface Schemes and Themes Technicalities Note on abbreviations Chapter 1 Introduction: Lumbinī, a Buddhist World Exposition 1.1 Theravāda and Mahāyāna 1.2 Lumbinī’s Eastern Monastic Zone: South and Southeast Asian Traditions 1.2.1 The Mahā Bodhi Society 1.2.2 The Sri Lanka Monastery 1.2.3 The Gautamī Center for Nuns 1.2.4 Myanmar (Burma) 1.2.5 Meditation Centers 1.3 Lumbinī’s Western Monastic Zone: East Asian Traditions 1.3.1 China 1.3.2 Korea 1.3.3 Japan 1.3.4 Vietnam 4 1.4 Lumbinī’s Western Monastic Zone: Tibetan Vajrayāna Traditions 1.4.1 The Great Lotus Stūpa 1.4.2 The Lumbinī Udyana Mahachaitya Part I: Foundations of the Triple Gem: Buddha/s, Dharma/s, and Saṃgha/s Chapter 2 Śākyamuni, Lives and Legends 2.1 The Historical Buddha 2.2 The Buddha’s World 2.3 The Buddha of Story 2.4 Past Buddhas and the Biographical Blueprint 2.5 The Start of Śākyamuni’s Career 2.6 Previous Lives (Jātakas) 2.6.1 The Donkey in the Lion’s Skin -

Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture

Thesis Title: Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture In fulfilment of the requirements of Master’s in Theology (Missiology) Submitted by: Gerard G. Ravasco Supervised by: Dr. Bill Domeris, Ph D March, 2004 Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The world we live in 1 1.2 The particular world we live in 1 1.3 Our target location: Cambodia 2 1.4 Our Particular Challenge: Cambodian Culture 2 1.5 An Invitation to Inculturation 3 1.6 My Personal Context 4 1.6.1 My Objectives 4 1.6.2 My Limitations 5 1.6.3 My Methodology 5 Chapter 2 2.0 Religious Influences in Early Cambodian History 6 2.1 The Beginnings of a People 6 2.2 Early Cambodian Kingdoms 7 2.3 Funan 8 2.4 Zhen-la 10 2.5 The Founding of Angkor 12 2.6 Angkorean Kingship 15 2.7 Theravada Buddhism and the Post Angkorean Crisis 18 2.8 An Overview of Christianity 19 2.9 Conclusion 20 Chapter 3 3.0 Religions that influenced Cambodian Culture 22 3.1 Animism 22 3.1.1 Animism as a Philosophical Theory 22 3.1.2 Animism as an Anthropological Theory 23 3.1.2.1 Tylor’s Theory 23 3.1.2.2 Counter Theories 24 3.1.2.3 An Animistic World View 24 3.1.2.4 Ancestor Veneration 25 3.1.2.5 Shamanism 26 3.1.3 Animism in Cambodian Culture 27 3.1.3.1 Spirits reside with us 27 3.1.3.2 Spirits intervene in daily life 28 3.1.3.3 Spirit’s power outside Cambodia 29 3.2 Brahmanism 30 3.2.1 Brahmanism and Hinduism 30 3.2.2 Brahmin Texts 31 3.2.3 Early Brahmanism or Vedism 32 3.2.4 Popular Brahmanism 33 3.2.5 Pantheistic Brahmanism -

Sambodh Samyak

IBC Newsletter Samyak Sambodh VOLUME III ISSUE 2 JULY-SEPTEMBER 2019 COUNCIL OF PATRONS ‘Let’s restore and move on’: His Holiness Thich Tri Quang Deputy Patriarch, Vietnam Buddhist Sangha, Vietnam ABCP held in Mongolia His Holiness Samdech Preah Agga Maha Sangharajadhipati Tep Vong PM Modi gifts Supreme Patriach, Mahanikaya Order, Cambodia Buddha statue His Holiness Dr. Bhaddanta Kumarabhivamsa Sangharaja and Chairman, State Sangha Mahanayaka Committee, Myanmar His Holiness Sanghanayaka Suddhananda Mahathero President, Bangladesh Bouddha Kristi Prachar Sangha, Bangladesh His Holiness Jinje-Beopwon 13th Supreme Patriarch, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, South Korea His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso India (Tibet in Exile) His Eminence Rev. Khamba Lama Gabju Choijamts Supreme Head of Mongolian Buddhists, Mongolia His Eminence 24th Pandito Khamba Lama Damba Ayusheev Prayers at the inauguration of the 11th General Assembly of Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace Supreme Head of Russian Buddhists, Russia (ABCP) at the Gandan Tegchenling Monastery His Holiness Late Somdet Phra Nyanasamvara Suvaddhana Mahathera he 11th General Assembly of Asian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Mongolia Supreme Patriarch, Thailand His Holiness Late Phra Achan Maha Phong Buddhist Conference for Peace in May 2015, that he announced the gifting Samaleuk T(ABCP) was held in Ulaanbaatar, of a Buddha statue with his two disciples Sangharaja, Laos from 21-23 June, 2019 at Mongolia’s to the Gandan Tegchenling Monastery. His Holiness Late Aggamaha Pandita leading monastery Gandan Tegchenling The Indian Council for Cultural Davuldena Gnanissara Maha Nikaya Thero Monastery, under the benevolent gaze of a Relations-ICCR was assigned the Mahanayaka, Amarapura Nikaya, Sri Lanka huge Statue of Lord Buddha with his two responsibility of commissioning the disciples.