Re-Imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat During the People's Republic Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Delegation

An invitation to experience Cambodia’s transformation through the arts Cultural Delegation 10 days-9 nights Siem Reap . Battambang Phnom Penh January 29 - February 07, 2018 August 06 - August 15, 2018 January 28 - February 06, 2019 An Invitation On behalf of Cambodian Living Arts, I would like to personally invite you on an exclusive journey through the Kingdom of Cambodia. Our Cultural Delegations give you an insight into Cambodia like no other, through a unique blend of tourism and personal encounters with the people who’ve contributed to the country’s cultural re-emergence. With almost 20 years of experience, CLA has grown into one of the leading arts and cultural institutions in Cambodia. What began as a small program supporting four Master Artists has blossomed into a diverse and wide-reaching organization providing opportunities for young artists and arts leaders, supporting arts and culture education in Cambodia, expanding audiences and markets for Cambodian performing arts, and building links with our neighbors in the region. We would love for you to come and experience this transformation through the arts for yourself. Our Cultural Delegation will give you the chance to see the living arts in action and to meet artists, students and partners working to support and develop Cambodia’s rich artistic heritage. Through these intimate encounters you will come to understand the values and aspirations of Cambodian artists, the obstacles they face, and the vital role that culture plays in society here. Come with us and discover the impressive talents of this post-conflict nation and the role that you can play as an agent of change to help develop, sustain and grow the arts here in the Kingdom of Culture. -

Sthapatyakam. the Architecture of Cambodia

STHAPATYAKAM The Architecture of Cambodia ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ The “Stha Patyakam” magazine team in front of Vann Molyvann’s French Library on the RUPP Campus Supervisor Dr. Tilman Baumgärtel Thanks to Yam Sokly, Heritage Mission, who has Design Supervisor Christine Schmutzler shared general knowledge about architecture in STHAPATYAKAM Editorial Assistant Jenny Nickisch Cambodia, Oun Phalline, Director of National Museum, The Architecture of Cambodia Writers and Editors An Danhsipo, Bo Sakalkitya, Sok Sophal, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Chey Phearon, Chhuon Sophorn, Cheng Bunlong, for an exclusive interview, Chheang Sidath, architect at Dareth Rosaline, Heng Guechly, Heang Sreychea, Ly Chhuong Import & Export Company, Nhem Sonimol, ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ Kun Chenda, Kim Kotara, Koeut Chantrea, Kong Sovan, architect student, who contributed the architecture Leng Len, Lim Meng Y, Muong Vandy, Mer Chanpolydet, books, Chhit Vongseyvisoth, architect student, A Plus Sreng Phearun, Rithy Lomor Pich, Rann Samnang, who contributed the Independence Monument picture, Samreth Meta, Soy Dolla, Sour Piset, Song Kimsour, Stefanie Irmer, director of Khmer Architecture Tours, Sam Chanmaliny, Ung Mengyean, Ven Sakol, Denis Schrey from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Phnom Department of Media and Communication Vorn Sokhan, Vann Chanvetey, Yar Ror Sartt, Penh for financial support of the printing, to the Royal University of Phnom Penh Yoeun Phary, Nou Uddom. Ministry of Tourism that has contributed the picture of Russian Boulevard, Phnom Penh Illustrator Lim -

Language and Culture of Cambodia SFS 2080

Language and Culture of Cambodia SFS 2080 Syllabus The School for Field Studies (SFS) Center for Conservation and Development Studies Siem Reap, Cambodia This syllabus may develop or change over time based on local conditions, learning opportunities, and faculty expertise. Course content may vary from semester to semester. www.fieldstudies.org © 2019 The School for Field Studies Fa19 COURSE CONTENT SUBJECT TO CHANGE Please note that this is a copy of a recent syllabus. A final syllabus will be provided to students on the first day of academic programming. SFS programs are different from other travel or study abroad programs. Each iteration of a program is unique and often cannot be implemented exactly as planned for a variety of reasons. There are factors which, although monitored closely, are beyond our control. For example: • Changes in access to or expiration or change in terms of permits to the highly regulated and sensitive environments in which we work; • Changes in social/political conditions or tenuous weather situations/natural disasters may require changes to sites or plans, often with little notice; • Some aspects of programs depend on the current faculty team as well as the goodwill and generosity of individuals, communities, and institutions which lend support. Please be advised that these or other variables may require changes before or during the program. Part of the SFS experience is adapting to changing conditions and overcoming the obstacles that may be present. In other words, the elephants are not always where we want them to be, so be flexible! 2 Course Overview The Language and Culture course contains two distinct but related modules: Cambodian society and culture, and Khmer language. -

Exploring the Utilization of Buddhist Practices in Counseling for Two Different Groups of Service Providers (Monks and Psychologists) in Cambodia

Exploring the Utilization of Buddhist Practices in Counseling for Two Different Groups of Service Providers (Monks and Psychologists) in Cambodia Khann Sareth and Tanja E Schunert1; Taing S Hun, Lara Petri, Lucy Wilmann, Vith Kimly, Judith Strasser, and Chor Sonary2 The suffering of Cambodia has been deep. From this suffering comes great Compassion. Great Compassion makes a Peaceful Heart. A peaceful Heart makes a Peaceful Person. A Peaceful Person makes a Peaceful Community. A Peaceful Community makes a Peaceful Nation. And a Peaceful Nation makes a Peaceful World. May all beings live in Happiness and Peace. --Samdech Maha Ghosananda, Cambodia The above quotation sets the objective we advocate and work for in Cambodia.3 Introductory analysis Background and current situation: Cambodia’s history of political unrest, socioeconomic struggle and traumatic genocide under the Khmer Rouges (KR) has disrupted and destroyed many grown structures of resources, such as the foundations of sufficient health care, education and deeper knowledge of Buddhist and Hindu, animistic traditional practices and cultural legacies. Normal patterns and habits of daily life have been torn apart and resulted in low indicators of development. Cambodia was ranked 137th out of 182 countries according to the United Nations Human Development Index (2009) and struggles still with providing a minimum of health services and standards especially in the field of mental health. Problems such as poverty, lack of gender parity, mistrust and suppressed anger, domestic violence, child and sex-trafficking, substance abuse, and other issues which continue to undermine movements for national reconciliation, are common (Human Rights Watch, 2010; Humeniuk, Ali, & Ling, 2004; UNIAP, 2008; van de Put & Eisenbruch, 2002). -

The Emergence of Cambodian Women Into the Public

WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Joan M. Kraynanski June 2007 WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE by JOAN M. KRAYNANSKI has been approved for the Center for International Studies by ________________________________________ Elizabeth Fuller Collins Associate Professor, Classics and World Religions _______________________________________ Drew McDaniel Interim Director, Center for International Studies Abstract Kraynanski, Joan M., M.A., June 2007, Southeast Asian Studies WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE (65 pp.) Director of Thesis: Elizabeth Fuller Collins This thesis examines the changing role of Cambodian women as they become engaged in local politics and how the situation of women’s engagement in the public sphere is contributing to a change in Cambodia’s traditional gender regimes. I examine the challenges for and successes of women engaged in local politics in Cambodia through interviews and observation of four elected women commune council members. Cambodian’s political culture, beginning with the post-colonial period up until the present, has been guided by strong centralized leadership, predominantly vested in one individual. The women who entered the political system from the commune council elections of 2002 address a political philosophy of inclusiveness and cooperation. The guiding organizational philosophy of inclusiveness and cooperation is also evident in other women centered organizations that have sprung up in Cambodia since the early 1990s. My research looks at how women’s role in society began to change during the Khmer Rouge years, 1975 to 1979, and has continued to transform, for some a matter of necessity, while for others a matter of choice. -

Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - the Case for the Prosecution

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 12 Issue 3 Justice and the Prevention of Genocide Article 7 12-2018 Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution William Smith Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Smith, William (2018) "Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 12: Iss. 3: 20-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.12.3.1658 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss3/7 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution Acknowledgements This address was prepared with the assistance of Caroline Delava, Martin Hardy and Andreana Paz, legal interns in the Office of the Co-Prosecutor. The opinions in this address are those of the author solely and reflect the concepts and essence of the address delivered at the Conference. This conference proceeding is available in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss3/7 Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution William Smith Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia Phnom Penh, Cambodia The Importance of Contemporaneous Documents and Academic Activism* Figure 1. -

Economic History of Industrialization in Cambodia

Working Paper No. 7 Economic history of industrialization in Cambodia 1 2 Sokty Chhair and Luyna Ung Abstract The industrialization which started in 1953 had been completely disrupted by the chronic civil war and closed-door policy of successive communism/socialism regimes. Since 1993 Cambodia has embraced a market economy heavily dependent on foreign capital and foreign markets. As a result, the economy has experienced high economic growth rate yet with low linkage to domestic economy. The government’s Rice Export Policy introduced in 2010 to diversify its economy, maximize its value added and job creation was highly evaluated to bring those benefits under the environment of weak governance. Whether similar kind of such a policy for other sectors is successful remains to be seen. Keywords: industrialization, mixed economy, cooperative, garment sector, Cambodia JEL classification: L2, L52 1 1Cambodian Economic Association; 2Supreme National Economic Council; corresponding author email: [email protected]. The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined or influenced by any donation. Learning to Compete (L2C) is a collaborative research program of the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings (AGI), the African Development Bank, (AfDB), and the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER) on industrial development in Africa. -

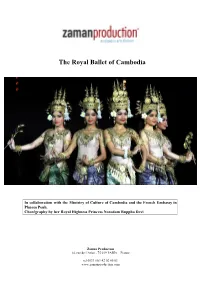

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia In collaboration with the Ministry of Culture of Cambodia and the French Embassy in Phnom Penh. Chorégraphy by her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Zaman Production 14, rue de l’Atlas - 75 019 PARIS – France tel 0033 (0)1 42 02 00 03 www.zamanproduction.com IMMATERIAL HERITAGE UNESCO duration : 1h20 UNESCO : Choreography by Her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Renowned for its graceful hand gestures and stunning costumes, the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, also known as Khmer Classical Dance, has been closely associated with the Khmer court for over one thousand years. Performances would traditionally accompany royal ceremonies and observances such as coronations, marriages, funerals or Khmer holidays. This art form, which narrowly escaped annihilation in the 1970s, is cherished by many Cambodians. Infused with a sacred and symbolic role, the dance embodies the traditional values of refinement, respect and spirituality. Its repertory perpetuates the legends associated with the origins of the Khmer people. Consequently, Cambodians have long esteemed this tradition as the emblem of Khmer culture. Four distinct character types exist in the classical repertory: Neang the woman, Neayrong the man, Yeak the giant, and Sva the monkey. Each possesses distinctive colours, costumes, makeup and masks.The gestures and poses, mastered by the dancers only after years of intensive training, evoke the gamut of human emotions, from fear and rage to love and joy. An orchestra accompanies the dance, and a female chorus provides a running commentary on the plot, highlighting the emotions mimed by the dancers, who were considered the kings’ messengers to the gods and to the ancestors. -

The Cambodian Civil War and the Vietnam War

THE CAMBODIAN CIVIL WAR AND THE VIETNAM WAR: A TALE OF TWO REVOLUTIONARY WARS by Boraden Nhem A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Spring 2015 €•' 2015 Boraden Nhem All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 3718366 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 3718366 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 THE CAMBODIAN CIVIL WAR AND THE VIETNAM WAR: A TALE OF TWO REVOLUTIONARY WARS by Boraden Nhem Approved: _________________________________________________________________ Gretchen Bauer, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: _____________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: _________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Hear the Cry of the Earth and the Poor Whakarongo Ki Te Tangi O Papatūānuku Me Te Hunga Pōhara

LENT 2016 TEACHER’S BOOKLET Hear the cry of the earth and the poor Whakarongo ki te tangi o Papatūānuku me te hunga pōhara We need to strengthen the conviction that we are one single human family. Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, #52 Introduction Food Security Climate Change This year’s school resource In September 2015 the United Nations announced its 2030 In his recent encyclical, Laudato Si’, Pope Francis says that the for Lent focuses on the Agenda for Sustainable Development. Among its 17 goals to negative effects of climate change are felt most by those who be achieved by 2030 is ending hunger and ensuring access have made the smallest contribution to it: the poor. experiences and challenges by all people to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year In Cambodia, the effects of climate change are experienced of Cambodians living in round. In order to do this they have a target of doubling the by small farmers who notice that the wet season rainfall has agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale farmers. rural areas. Students will increased and the dry season rainfall has decreased. They This means small food producers will be supported with learn about the rich culture experience long periods of drought and then flash-flooding. In training, financial services, access to markets and fair access the past, flooding has resulted in the destruction of more than and recent sad history of to land. Cambodia, while being half the rice crop of the entire country. This trend looks set to Development and Partnership in Action, Cambodia (DPA) continue unless Cambodia’s farmers can learn to adapt their exposed to social justice and Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand are working with small agricultural methods to the changing weather patterns. -

Society and Culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian Period Under the Influence of Buddhism

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 8 (2021), 2420-2423 Research Article Society and Culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian Period under the influence of Buddhism Phra Ratchawimonmolia, Phra Dhammamolee, (Thongyoo) Drb. Phra Khrupanyasudhammanitesc, Phramaha Yuddhapicharn Thongjunrad, Thanarat Sa-ard-iame a,b,e Department of Buddhist Studies, c Department of Political Science, d Department of Public Administration a,b,c,d,e Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Surin Campus, Thailand a [email protected], b [email protected], c [email protected], d [email protected], e [email protected] Article History: Received: 10 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 20 April 2021 Abstract: The purposes of this article were 1) to present the society and culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian period, 2) to discover Buddhism in the Angkorian period, and) to analyze the influence of Buddhism on the society and culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian period. This relies on the primary source of data used in the documentary research. The methodology adopted in the study is of a critical and investigative approach to the analysis of data gathered from documentary sources. The result indicated that: ancient Cambodia inherited civilization from India. The ancient Cambodians, therefore, respected both Brahmin and Buddhism. The Cambodian way of life in the Angkorian era was primarily agricultural occupation, and the monarchy was the ultimate leader. Buddhism has spread in Cambodia after the finishing of the 3rd Buddhist Council. The king accepted Buddhism as the Code of conduct and carried on for a period. -

Bringing the Khmer Rouge to Justice: the Challenges and Risks Facing the Joint Tribunal in Cambodia Katheryn M

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 4 | Issue 3 Article 4 Spring 2006 Bringing the Khmer Rouge to Justice: The Challenges and Risks Facing the Joint Tribunal in Cambodia Katheryn M. Klein Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Katheryn M. Klein, Bringing the Khmer Rouge to Justice: The Challenges and Risks Facing the Joint Tribunal in Cambodia, 4 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 549 (2006). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol4/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2006 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 4, Issue 3 (Spring 2006) Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Bringing the Khmer Rouge to Justice: The Challenges and Risks Facing the Joint Tribunal in Cambodia Katheryn M. Klein* I. INTRODUCTION ¶1 The time for justice is running out. Over thirty years have passed since the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, and overthrew the Khmer Republic in order to carry out their violent plan to transform Cambodia into an agrarian, communist society. 1 From April 1975 until January 1979, the Khmer Rouge subjected citizens to forced labor, torture and genocide.2 Two to three million Cambodians were forced to evacuate their urban homes