1 Post-Canonical Buddhist Political Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies

UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM FORPOST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN THE DEPARTMENT OF BUDDHIST STUDIES W.E.F. THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies Nomenclature of courses will be done in such a way that the course code will consist of eleven characters. The first character ‘P’ stands for Post Graduate. The second character ‘S’ stands for Semester. Next two characters will denote the Subject Code. Subject Subject Code Buddhist Studies BS Next character will signify the nature of the course. T- Theory Course D- Project based Courses leading to dissertation (e.g. Major, Minor, Mini Project etc.) L- Training S- Independent Study V- Special Topic Lecture Courses Tu- Tutorial The succeeding character will denote whether the course is compulsory “C” or Elective “E”. The next character will denote the Semester Number. For example: 1 will denote Semester— I, and 2 will denote Semester— II Last two characters will denote the paper Number. Nomenclature of P G Courses PSBSTC101 P POST GRADUATE S SEMESTER BS BUDDHIST STUDIES (SUBJECT CODE) T THEORY (NATURE OF COURSE) C COMPULSORY 1 SEMESTER NUMBER 01 PAPER NUMBER O OPEN 1 Semester wise Distribution of Courses and Credits SEMESTER- I (December 2018, 2019, 2020 & 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC101 History of Buddhism in India 6 PSBSTC102 Fundamentals of Buddhist Philosophy 6 PSBSTC103 Pali Language and History 6 PSBSTC104 Selected Pali Sutta Texts 6 SEMESTER- II (May 2019, 2020 and 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC201 Vinaya -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

Curriculum Vitae of Jay L Garfield

Curriculum Vitae of Jay L Garfield Present Appointment Doris Silbert Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy, Smith College Director, Five Colleges Tibetan Studies in India Program Director, Logic Program Professor, Graduate Faculty of Philosophy, University of Massachusetts Professor of Philosophy, University of Melbourne Adjunct Professor of Philosophy, Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies Collaborateur Scientifique, Université de Lausanne Contact Details Address: Department of Philosophy Smith College Northampton, MA 01063 USA Phone: +1 413 585 3649 Fax: +1 413 585 3710 Secretary: +1 413 585 3642 E-mail: [email protected] Phone (India) +91 98399 00490 Phone (Australia) +614 1063 8965 Personal Details Date of Birth: November 13, 1955 Marital Status: Married, four children Citizenship: USA, Australia Home Address: 105 January Hills Road Amherst, MA 01002 Home Phone +1 413 548 9577 Education A.B., Oberlin College, 1975 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1976 PhD, University of Pittsburgh, 1986 Areas of Professional Interest Philosophy of Psychology, Cognitive Science, Philosophy of Mind, Philosophy of Language, Metaphysics, Epistemology, Buddhist Philosophy, Applied and Theoretical Ethics, Philosophy of Technology, Artificial Intelligence, Hermeneutics June 2008 Curriculum vitae of Prof Jay L Garfield page 2 Academic Honours Phi Beta Kappa Sigma Xi High Honours in Philosophy, Oberlin College High Honours in Psychology, Oberlin College Andrew Mellon Predoctoral Fellow in Philosophy, 1975-1976 Teaching Fellow in Philosophy, 1976-1980 Michael Bennett Memorial Philosophical Essay Prize, 1980 Fellow of the Academy of Finland, 1986-1987 Grants and Fellowships National Endowment for Humanities Summer Institute Fellowship (Nagarjuna), 1989 Fulbright Teaching/Research Grant, Sri Lanka 1990-1991 (declined) Indo-American Fellow, 1990-1991 Hewlett-Mellon Research Grants, 1993, 1994 (India) Culpepper Languages Across the Curriculum Grant 1994-1995. -

Buddhist " Protestantism" in Poland

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 13 Issue 2 Article 5 4-1993 Buddhist " Protestantism" in Poland Malgorzata Alblamowicz-Borri University of Paris Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Alblamowicz-Borri, Malgorzata (1993) "Buddhist " Protestantism" in Poland," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 13 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol13/iss2/5 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUDDHIST "PROTESTANTISM" IN POLAND by Malgorzata Ablamowicz - Borri Malgorzata Ablamowicz - Borri (Buddhist) received a master's degree at Universite de Paris X. This article is an resumme of her thesis.1 She also presented this topic at the UNESCO at the Tenth Congress of Buddhist Studies iti Paris, July 18-21, 1991. Currently she lives in Santa Barbara, California. I. Phases of Assimilation of Buddhism in the Occident I propose to divide the assimilation of Buddhism in the Occident into three phases: 1. The first phase was essentially intellectual; Buddhist texts were translated and submitted to philosophical analysis. In Poland, this phase appeared after World War I when Poland gained independence. Under the leadership of Andrzej Gawronski, Stanislaw Schayer, Stanislaw Stasiak, Arnold Kunst, Jan Jaworski and others, the Polish tradition of Buddhist studies formed mainly in two study centers, Lwow (now in Ukraine) and Warsaw. -

American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter

CHAPTER FO U R American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter ★ he Buddha’s Birthday is celebrated for weeks on end in Los Angeles. TMore than three hundred Buddhist temples sit in this great city fac- ing the Pacific, and every weekend for most of the month of May the Buddha’s Birthday is observed somewhere, by some group—the Viet- namese at a community college in Orange County, the Japanese at their temples in central Los Angeles, the pan-Buddhist Sangha Council at a Korean temple in downtown L.A. My introduction to the Buddha’s Birthday observance was at Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights, just east of Los Angeles. It is said to be the largest Buddhist temple in the Western hemisphere, built by Chinese Buddhists hailing originally from Taiwan and advocating a progressive Humanistic Buddhism dedicated to the pos- itive transformation of the world. In an upscale Los Angeles suburb with its malls, doughnut shops, and gas stations, I was about to pull over and ask for directions when the road curved up a hill, and suddenly there it was— an opulent red and gold cluster of sloping tile rooftops like a radiant vision from another world, completely dominating the vista. The ornamental gateway read “International Buddhist Progress Society,” the name under which the temple is incorporated, and I gazed up in amazement. This was in 1991, and I had never seen anything like it in America. The entrance took me first into the Bodhisattva Hall of gilded images and rich lacquerwork, where five of the great bodhisattvas of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition receive the prayers of the faithful. -

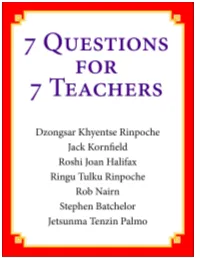

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture

Thesis Title: Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture In fulfilment of the requirements of Master’s in Theology (Missiology) Submitted by: Gerard G. Ravasco Supervised by: Dr. Bill Domeris, Ph D March, 2004 Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The world we live in 1 1.2 The particular world we live in 1 1.3 Our target location: Cambodia 2 1.4 Our Particular Challenge: Cambodian Culture 2 1.5 An Invitation to Inculturation 3 1.6 My Personal Context 4 1.6.1 My Objectives 4 1.6.2 My Limitations 5 1.6.3 My Methodology 5 Chapter 2 2.0 Religious Influences in Early Cambodian History 6 2.1 The Beginnings of a People 6 2.2 Early Cambodian Kingdoms 7 2.3 Funan 8 2.4 Zhen-la 10 2.5 The Founding of Angkor 12 2.6 Angkorean Kingship 15 2.7 Theravada Buddhism and the Post Angkorean Crisis 18 2.8 An Overview of Christianity 19 2.9 Conclusion 20 Chapter 3 3.0 Religions that influenced Cambodian Culture 22 3.1 Animism 22 3.1.1 Animism as a Philosophical Theory 22 3.1.2 Animism as an Anthropological Theory 23 3.1.2.1 Tylor’s Theory 23 3.1.2.2 Counter Theories 24 3.1.2.3 An Animistic World View 24 3.1.2.4 Ancestor Veneration 25 3.1.2.5 Shamanism 26 3.1.3 Animism in Cambodian Culture 27 3.1.3.1 Spirits reside with us 27 3.1.3.2 Spirits intervene in daily life 28 3.1.3.3 Spirit’s power outside Cambodia 29 3.2 Brahmanism 30 3.2.1 Brahmanism and Hinduism 30 3.2.2 Brahmin Texts 31 3.2.3 Early Brahmanism or Vedism 32 3.2.4 Popular Brahmanism 33 3.2.5 Pantheistic Brahmanism -

The Parinirvana Cycle and the Theory of Multivalence: a Study Of

THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE AND THE THEORY OF MULTIVALENCE: A STUDY OF GANDHĀRAN BUDDHIST NARRATIVE RELIEFS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2017 By Emily Hebert Thesis Committee: Paul Lavy, Chairperson Kate Lingley Jesse Knutson TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1. BUDDHISM IN GREATER GANDHĀRA ........................................................... 9 Geography of Buddhism in Greater Gandhāra ....................................................................... 10 Buddhist Textual Traditions in Greater Gandhāra .................................................................. 12 Historical Periods of Buddhism in Greater Gandhāra ........................................................... 19 CHAPTER 2. GANDHĀRAN STŪPAS AND NARRATIVE ART ............................................. 28 Gandhāran Stūpas and Narrative Art: Architectural Context ................................................. 35 CHAPTER 3. THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYLCE OF NARRATIVE RELIEFS ................................ 39 CHAPTER 4 .THE THEORY OF MULTIVALENCE AND THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE ...... 44 CHAPTER 5. NARRATIVE RELIEF PANELS FROM THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE ............ 58 Episode -

Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar

Policy Studies 71 Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar Matthew J. Walton and Susan Hayward Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar About the East-West Center The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for infor- mation and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US main- land and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. The Center is an independent, public, nonprofit organization with funding from the US government, and additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and govern- ments in the region. Policy Studies an East-West Center series Series Editors Dieter Ernst and Marcus Mietzner Description Policy Studies presents original research on pressing economic and political policy challenges for governments and industry across Asia, About the East-West Center and for the region's relations with the United States. Written for the The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding policy and business communities, academics, journalists, and the in- among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the formed public, the peer-reviewed publications in this series provide Pacifi c through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. -

Buddhism, Power and Political Order

BUDDHISM, POWER AND POLITICAL ORDER Weber’s claim that Buddhism is an otherworldly religion is only partially true. Early sources indicate that the Buddha was sometimes diverted from supra- mundane interests to dwell on a variety of politically related matters. The significance of Asoka Maurya as a paradigm for later traditions of Buddhist kingship is also well attested. However, there has been little scholarly effort to integrate findings on the extent to which Buddhism interacted with the polit- ical order in the classical and modern states of Theravada Asia into a wider, comparative study. This volume brings together the brightest minds in the study of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Their contributions create a more coherent account of the relations between Buddhism and political order in the late pre-modern and modern period by questioning the contested relationship between monastic and secular power. In doing so, they expand the very nature of what is known as the ‘Theravada’. This book offers new insights for scholars of Buddhism, and it will stimulate new debates. Ian Harris is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cumbria, Lancaster, and was Senior Scholar at the Becket Institute, St Hugh’s College, University of Oxford, from 2001 to 2004. He is co-founder of the UK Association for Buddhist Studies and has written widely on aspects of Buddhist ethics. His most recent book is Cambodian Buddhism: History and Practice (2005), and he is currently responsible for a research project on Buddhism and Cambodian Communism at the Documentation Center of Cambodia [DC-Cam], Phnom Penh. ROUTLEDGE CRITICAL STUDIES IN BUDDHISM General Editors: Charles S. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

The Tradition of Sangiti and Pali Literature Introduction Meaning of Sangiti

Session: The Traditionl of Pāḷi Studies 1 The Tradition Of Sangiti And Pali Literature Prof. Bhikshu Satyapala, Ph.D. Department of Buddhist Studies University of Delhi Delhi 110 007, India Introduction Pali literature named after its language, Pali, refers to the Literature of Theravada Buddhist canonical and non-canonical literatures. The form of the Pali literature, which we have at present, has come down to us through the tradition of Sangities. History of Buddhism has records of more than a dozen Sangiti which has, so far, been convened in order to recite and preserve the original form of the Buddha’s teaching. Of these twelve, only two Sangities (the Councils held in Kashmir and Lhasa) were organized by two Buddhist schools (other than Theravada), which adopted respectively Sanskrit and Tibetan languages as the mode of transmission of the Buddha’s teachings among their followers. It is the work of these Councils due to which we have been able to preserve from centuries the tradition and teachings of the Buddha. The Buddha’s teachings currently available in Pali, Tibetan, and Sanskrit (most of which though not available in its original form but in Chinese translations) are the result of the Sangities held from time to time. Hence, it appears pertinent, firstly, to decipher the meaning of the term Sangiti and the role played by it. Meaning of Sangiti 1 The paper was presented in the International Conference of Theravada Buddhist Universities organized by International Theravada Buddhist Missionary University (ITBMU) and read in group discussion held under the chairmanship of Ven. Venerable Dr.