A Vision for Reconciliation in Anlong Veng, Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

History a Work in Progress in One-Time KR Stronghold May Titthara January 25, 2011

History a work in progress in one-time KR stronghold May Titthara January 25, 2011 Sitting under a tree outside Malai High School, 20-year-old Phen Soeurm offers a dismissive approach to his history class typical of many his age. As the teacher lectures, “the class just listens without paying attention at all,” Phen Soeurm says. “They just want to kill time.” Here in this dusty district of Banteay Meanchey province, however, there is more to this phenomenon than a simple case of student laziness. The lecture in question covers the history of the Democratic Kampuchea regime, an understandably sensitive topic in this former Khmer Rouge stronghold. “Most students don’t want to study Khmer Rouge history because they don’t want to be reminded of what happened, and because all of their parents are former Khmer Rouge,” Phen Soeurm said. In schools throughout the Kingdom, the introduction of KR-related material has been a sensitive project. Prior to last year, high school history tests drew from a textbook that gave short shrift to the regime and its history, omitting some of the most basic facts about it. But on the 2010 national history exam, five of the 14 questions dealt with the Khmer Rouge period. In addition to identifying regime leaders, students are asked to explain why it is said that Tuol Sleng prison was a tragedy for the Cambodian people; who was behind Tuol Sleng; how the administrative zones of Democratic Kampuchea were organised; and when the regime was in power. These new additions to the exam follow the 2007 introduction of a government-approved textbook created by the Documentation Centre of Cambodia titled A History of Democratic Kampuchea. -

First Quarterly Report: January-March, 2012

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia Quarterly Report: January‐March, 2012 DC‐Cam Team Leaders and the Management Team Prepared and Compiled by Farina So Office Manager Edited by Norman (Sambath) Pentelovitch April, 2012 Sirik Savina, Outreach Coordinator, discusses with the villagers about the hearing process at Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Abbreviations CHRAC Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee CP Civil Party CTM Cambodia Tribunal Monitor DC‐Cam Documentation Center of Cambodia DK Democratic Kampuchea ECCC Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia ICC International Criminal Court ITP Sida Advanced International Training Programme KID Khmer Institute for Democracy KR Khmer Rouge MMMF Margaret McNamara Memorial Fund MRDC Mondul Kiri Resource and Documentation Centre OCP Office of Co‐Prosecutors OCIJ Office of Co‐Investigating Judges PTSD Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Sida Swedish International Development Agency TSL Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum UN United Nations UNDP United Nation for Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VOT Victims of Torture VPA Victims Participation Project VSS Victim Support Section YFP Youth for Peace YRDP Youth Resource Development Program 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Results/Outcome................................................................................................................. 7 Raised Public Awareness on the Value of Documents............................................. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

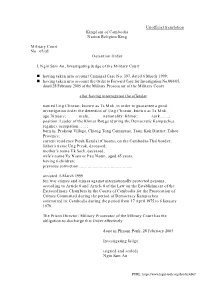

Ung Choeun, Known As Ta

Unofficial translation Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Military Court No 07/05 Detention Order I, Ngin Sam An, Investigating Judge of the Military Court n having taken into account Criminal Case No. 397, dated 6 March 1999; n having taken into account the Order to Forward Case for Investigation No.004/05, dated 28 February 2005 of the Military Prosecutor of the Military Court after having interrogated the offender named Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, in order to guarantee a good investigation order the detention of Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, age 78 years; male; nationality: Khmer; rank…….; position: Leader of the Khmer Rouge (during the Democratic Kampuchea regime); occupation……; born in Prakeap Village, Chieng Tong Commune, Tram Kok District, Takeo Province; current residence Pteah Kandal (Choam), on the Cambodia-Thai border; father’s name Ung Preak, deceased; mother’s name Uk Soch, deceased; wife’s name Vy Naen or Pau Naem, aged 45 years; having 6 children; previous conviction:………………………………… arrested: 6 March 1999 for: war crimes and crimes against internationally protected persons, according to Article 6 and Article 8 of the Law on the Establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for the Prosecution of Crimes Committed during the period of Democracy Kampuchea committed in: Cambodia during the period from 17 April 1975 to 6 January 1979. The Prison Director/Military Prosecutor of the Military Court has the obligation to discharge this Order effectively done in Phnom Penh, 28 February 2005 Investigating -

Data Collection Survey on Electric Power Sector in Cambodia Final Report

Kingdom of Cambodia Data Collection Survey on Electric Power Sector in Cambodia Final Report March 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) The Chugoku Electric Power Co., Inc. SAP JR 12 -021 Data Collection Survey on Electric Power Sector in Cambodia Final Report Contents Chapter 1 Background, Objectives and Scope of Study……...............................................................1-1 1.1 Background of the Study………....................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Objectives of the Study...................................................................................................................1-1 1.3 Supported agencies of the study.....................................................................................................1-2 1.4 Road map of study..........................................................................................................................1-2 Chapter 2 Current Status of the Power Sector in Cambodia................................................................2-1 2.1 Organizations of the Power Sector.................................................................................................2-1 2.1.1 Structure of the power sector.............................................................................................2-1 2.1.2 MIME................................................................................................................................2-1 2.1.3 EAC...................................................................................................................................2-3 -

Report on Power Sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia

ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY OF CAMBODIA REPORT ON POWER SECTOR OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 2013 EDITION Compiled by Electricity Authority of Cambodia from Data for the Year 2012 received from Licensees Electricity Authority of Cambodia ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY OF CAMBODIA REPORT ON POWER SECTOR OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 2013 EDITION Compiled by Electricity Authority of Cambodia from Data for the Year 2012 received from Licensees Report on Power Sector for the Year 2012 0 Electricity Authority of Cambodia Preface The Annual Report on Power Sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2013 Edition is compiled from informations for the year 2012 availble with EAC and received from licensees, MIME and other organizations in the power sector. The data received from some licensees may not up to the required level of accuracy and hence the information provided in this report may be taken as indicative. This report is for dissemination to the Royal Government, institutions, investors and public desirous to know about the situation of the power sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia during the year 2012. With addition of more HV transmission system and MV sub-transmission system, more and more licensees are getting connected to the grid supply. This has resulted in improvement in the quality of supply to more consumers. By end of 2012, more than 91% of the consumers are connected to the grid system. More licensees are now supplying electricity for 24 hours a day. The grid supply has reduced the cost of supply and consequently the tariff for supply to consumers. Due to lower cost and other measures taken by Royal Government of Cambodia, in 2012 there has been a substantial increase in the number of consumers availing electricity supply. -

Searching for the TRUTH

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH w Reconciliation from the Destruction of the Genocide w Phnom Kraol Security Center and Cardres Purged at Region 105 “Recalling May 20th makes me think about the Khmer Rouge regime SpecialEnglish Edition and especially the death of my father. The Khmer Rouge forced my Second Quater 2016 father to dig the grave to bury himself” -- Rous Vannat, Khmer Rouge Survivor Searching for the truth. TABLE OF CONTENTS Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Special English Edition, Second Quarter 2016 EDITORIAL u Reconciliation from the Destruction of the Genocide.....................................1 DOCUMENTATION u Ty Sareth and the Traitorous Plans Against Angkar..........................................3 u Men Phoeun Chief of Statistics of the North-West Region.............................7 u News for Revolutionary Male and Female Youth...........................................13 HISTORY u I Believe in Good Deeds.............................................................................................16 u My Uncle Died because of Visting Hometown.................................................20 u The Murder in Region 41 under the Control of Ta An.................................22 u May 20: The Memorial of My Father’s Death....................................................25 u Ouk Nhor, Former Sub-Chief of Prey Pdao Cooperative..............................31 u Nuon Chhorn, Militiawoman...................................................................................32 -

Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia a Synthesis of Findings from Research on Appropriation and Derived Rights to Land

Études et Travaux en ligne no 18 Pel Sokha, Pierre-Yves Le Meur, Sam Vitou, Laing Lan, Pel Setha, Hay Leakhena & Im Sothy Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia A Synthesis of Findings from Research on Appropriation and Derived Rights to Land LES ÉDITIONS DU GRET Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia Document Reference Pel Sokha, Pierre-Yves Le Meur, Sam Vitou, Laing Lan, Pel Setha, Hay Leakhen & Im Sothy, 2008, Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia : A synthesis of Findings from Research on Appropriation and Derived Rights to Land, Coll. Études et Travaux, série en ligne n°18, Éditions du Gret, www.gret.org, May 2008, 249 p. Authors: Pel Sokha, Pierre-Yves Le Meur, Sam Vitou, Laing Lan, Pel Setha, Hay Leakhen & Im Sothy Subject Area(s): Land Transactions Geographic Zone(s): Cambodia Keywords: Rights to Land, Rural Development, Land Transaction, Land Policy Online Publication: May 2008 Cover Layout: Hélène Gay Études et Travaux Online collection This collection brings together papers that present the work of GRET staff (research programme results, project analysis documents, thematic studies, discussion papers, etc.). These documents are placed online and can be downloaded for free from GRET’s website (“online resources” section): www.gret.org They are also sold in printed format by GRET’s bookstore (“publications” section). Contact: Éditions du Gret, [email protected] Gret - Collection Études et Travaux - Série en ligne n° 18 1 Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia Contents Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................. -

Cambodian Journal of Natural History

Cambodian Journal of Natural History Giant ibis census Patterns of salt lick use Protected area revisions Economic contribution of NTFPs New plants, bees and range extensions June 2016 Vol. 2016 No. 1 Cambodian Journal of Natural History ISSN 2226–969X Editors Email: [email protected] • Dr Neil M. Furey, Chief Editor, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. • Dr Jenny C. Daltry, Senior Conservation Biologist, Fauna & Flora International, UK. • Dr Nicholas J. Souter, Mekong Case Study Manager, Conservation International, Cambodia. • Dr Ith Saveng, Project Manager, University Capacity Building Project, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. International Editorial Board • Dr Stephen J. Browne, Fauna & Flora International, • Dr Sovanmoly Hul, Muséum National d’Histoire Singapore. Naturelle, Paris, France. • Dr Martin Fisher, Editor of Oryx – The International • Dr Andy L. Maxwell, World Wide Fund for Nature, Journal of Conservation, Cambridge, U.K. Cambodia. • Dr L. Lee Grismer, La Sierra University, California, • Dr Brad Pett itt , Murdoch University, Australia. USA. • Dr Campbell O. Webb, Harvard University Herbaria, • Dr Knud E. Heller, Nykøbing Falster Zoo, Denmark. USA. Other peer reviewers for this volume • Prof. Leonid Averyanov, Komarov Botanical Institute, • Neang Thy, Minstry of Environment, Cambodia. Russia. • Dr Nguyen Quang Truong, Institute of Ecology and • Prof. John Blake, University of Florida, USA. Biological Resources, Vietnam. • Dr Stephan Gale, Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden, • Dr Alain Pauly, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Hong Kong. Sciences, Belgium. • Fredéric Goes, Cambodia Bird News, France. • Dr Colin Pendry, Royal Botanical Garden, Edinburgh, • Dr Hubert Kurzweil, Singapore Botanical Gardens, UK. Singapore. • Dr Stephan Risch, Leverkusen, Germany. • Simon Mahood, Wildlife Conservation Society, • Dr Nophea Sasaki, University of Hyogo, Japan. -

A Comparative Study of Transitional Justice Between the Rwandan

Theiring: The Policy of Truth: A Comparative Study of Transitional Justice Theiringcamera ready (Do Not Delete) 6/20/2018 11:11 AM COMMENT THE POLICY OF TRUTH: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE BETWEEN THE RWANDAN GACACA COURT AND THE EXTRAORDINARY CHAMBERS IN THE COURTS OF CAMBODIA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 160 I. RWANDA AND THE GACACA COURT ....................................... 164 A. Formation .................................................................... 164 B. Structure ...................................................................... 165 C. Categories of Crimes .................................................. 166 D. Procedural Methods and Problems ............................ 168 II. THE EXTRAORDINARY CHAMBERS IN THE COURTS OF CAMBODIA ....................................................................... 170 A. Formation ................................................................... 170 B. Structure ..................................................................... 172 C. Administrative Divisions of the Court ........................ 173 1. Support for the Victims During the Process ........ 173 2. Access to Legal Counsel for Defendants ............. 174 3. A Central Office that Provides Support and Stability ................................................................ 175 D. Procedural Methods .................................................. 176 1. Role of the Victim ................................................ -

Conflicting Sites of Memory in Post-Genocide Cambodia

Brigitte Sion Conflicting Sites of Memory in Post-Genocide Cambodia A new road connects the towns of Siem Reap to Along Veng, in northern Cambodia; it now takes less then two hours from the temples of Angkor to reach the last bastion of the Khmer Rouge, in what used to be a dense jungle. It is enough time for my driver, thirty-one-year-old Vann, to tell me the story of his family. ‘‘Every Cambodian family has lost relatives under the Khmer Rouge,’’ he says. Vann’s mother lost her husband and children in the early years of Pol Pot’s murderous regime. She remarried and gave birth to a new set of children, including Vann. ‘‘A total of ten family members died,’’ he sums up. Later, when Vann was in school, he was required, along with all residents of his village outside Siem Reap, to excavate the killing fields and exhume the bodily remains for cremation. ‘‘The smell was horrible,’’ he recalls. ‘‘I see too many bones. It scares me.’’ For years, Vann avoided the former mass graves. ‘‘My children don’t know what happened.’’ A Khmer song is playing in the car. ‘‘Old music from the 1960s,’’ he says by means of introduction. ‘‘The singer was killed.’’ We pass Along Veng and continue through the lush countryside and rice fields toward the Thai border. It takes a number of stops and questions, and a few dollars, to find the cremation site of Pol Pot, who was burned hastily in 1998 on a pile of rubbish. It is hidden behind a house, amid high weeds, junk, and garbage.