Humanistic Buddhists and Social Liberation (I)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Chan Buddhism During the Times of Yixuan and Hsing Yun

The JapaneseAssociationJapanese Association of Indian and Buddhist Studies Joumal ofJndian and Buddhist Studies Vol, 64, No. 3, March 2016 (261) Times of Chan Buddhism duringthe and Hsing Yun: Yixuan Applying Chinese Chan Principles to Contemporary Society SHIJuewei i} Lirlji Yixuan uttaXil( (d. 866) and Fo Guang Hsing Yun es)kZg:- (1927-), although separated by rnore than a millennium, innovatively applied Chan teachings to the societies in which they lived to help their devotees discover their humanity and transcend their existential conditions. Both religious leaders not only survived persecution, but brought their faiths to greater heights. This paper studies how these masters adapted Chan Buddhist teachings to the woes and conditions of their times. In particular, I shall review how yixuan and Hsing yun adapted the teachings of their predecessors, added value to the socio-political milieu of their times, and used familiar language to reconcile reality and their beliefs. Background These two Chan masters were selected because of the significance of their contributions. Lirlji Yixuan was not only the founder ofa popular Lirlji2) school in Chan Buddhism but was also posthumously awarded the title of Meditation Master of and Wisdom Illumination(HuizhaoChanshi ue,H", maeM)(Sasaki Kirchner 2oog, s2) by Emperor Yizong em7 of the Tang dynasty (r. 859-873). Hsing Yun, a very strong proponent ofHumanistic Buddhism, is currently the recipient of ls honorary doctorate degrees from universities around the world (Shi and Weng 2015). To have received such accolades, both Chan masters ought to have made momentous contribution to their societies. Although Yixuan and Hsing Yun had humble beginnings, they were well-grounded in Buddhist teachings. -

A Study of Gender Equality in Humanistic Buddhism

《 》學報 ‧ 藝文│第三十三期 外文論文 A Study of Gender Equality in Humanistic Buddhism Chang Hongxing Ph.D. Candidate, Nanjing University Abstract Since Humanistic Buddhism was first proposed by Master Taixu, the issue of gender equality has gradually kindled widespread discussion in the field of Buddhism. During the Republican Era, Master Taixu and the female Buddhists of the Pure Bodhi Vihara have actively expressed their views on gender equality. Eventually, they reached a consensus of respecting a woman’s character, protecting her rights, and advocating equal status between men and women. After 1949, under the impetus of Venerable Master Hsing Yun, Venerable Yin Shun, Venerable Sheng Yen, Venerable Chao- hwei, thoughts on gender equality in Taiwan have made great strides. After 1980, the rejuvenation of Humanistic Buddhism in Mainland China in turn developed thoughts on gender equality. As a result, the overall status of female Buddhists in Mainland China has remarkably improved. Keywords: Humanistic Buddhism, gender equality, Taiwan, Mainland China 176 A Study of Gender Equality in Humanistic Buddhism Since the beginning of Buddhism, women’s issues have always received great attention. There are discussions in the sūtras and the Vinaya (collection of monastic rules) concerning issues such as female renunciation, women’s status, and gender relations. In a nutshell, the attitude of ancient Indian Buddhism towards women has always cycled between respecting women and rejecting women. After Buddhism’s spread to China, due to China’s domestic politics, economics, cultures, and various other reasons, there was no lack of flash points in Chinese Buddhism regarding women. On the whole, the discrimination towards women derived from ancient Indian Buddhism persisted. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Taiwan's Tzu Chi As Engaged Buddhism

BSRV 30.1 (2013) 137–139 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (print) 0256-2897 doi: 10.1558/bsrv.v30i1.137 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (online) 1747-9681 Taiwan’s Tzu Chi as Engaged Buddhism: Origins, Organization, Appeal and Social Impact, by Yu-Shuang Yao. Global Oriental, Brill, 2012. 243pp., hb., £59.09/65€/$90, ISBN-13: 9789004217478. Reviewed by Ann Heirman, Oriental Languages and Cultures, Ghent University, Belgium. Keywords Tzu Chi, Taiwanese Buddhism, Engaged Buddhism Taiwan’s Tzu Chi as Engaged Buddhism is a well-written book that addresses a most interesting topic in Taiwanese Buddhism, namely the way in which Engaged Buddhism found its way into Taiwan in, and through, the Tzu Chi Foundation (the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation). Founded in 1966, the Foundation expanded in the 1990s, and so became the largest lay organiza- tion in a contemporary Chinese context. The overwhelming involvement of the laity introduced a new aspect, and has triggered major changes in Taiwanese Buddhism. The present book offers a most welcome comprehensive study of the Foundation, discussing its context, development, structure, teaching and prac- tices. With its focus on both the history and the social context, the work devel- ops an interesting interdisciplinary approach, offering valuable insights into the appeal of the movement to a Taiwanese public. Nevertheless, some remarks still need to be made. The work is based on research that was completed in 2001, and research updates have not been pro- duced since, apart from a small Afterword (pp. 228-230). Yet not publishing the present work would have been a loss to the scientific community. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

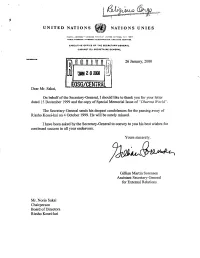

EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS ADRESSE POST ALE- UNITED NATIONS, N.V. 1OO17 CABLE AODflCSS ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: I/NATIONS NEWYORK EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL CABINET OU SECRETAIRE GENERAL REFERENCE: 26 January, 2000 EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr. Sakai, On behalf of the Secretary-General, I should like to thank you for your letter dated 15 December 1999 and the copy of Special Memorial Issue of "Dharma World". The Secretary-General sends his deepest condolences for the passing away of Rissho Kosei-kai on 4 October 1999. He will be surely missed. I have been asked by the Secretary-General to convey to you his best wishes for continued success hi all your endeavors. Yours sincerely, Gillian Martin Sorensen Assistant Secretary-General for External Relations Mr. Norio Sakai Chairperson Board of Directors Rissho Kosei-kai RISSHO KOSEI-KAI C, A BUDDHIST ORGANIZATION 2-11-1 Wada, Suginami-ku, Tokyo 166-8537, Japan, Tel: 03-3383-1111 lilJLU DEC 2 9 I999 December 15, 1999 Dear Sir/Madam, Special Memorial Issue of Dharrna World I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude for your friendship with Rissho Kosei-kai. As you may know, Founder Nikkyo Niwano peacefully passed away on October 4, 1999 at the age of 92. The enclosed Special Memorial Issue of Dharma World carries full details of the Founder's funeral ceremonies and a complete review of his life and work. I am very pleased to present this issue to you as a token of our wholehearted appreciation. Founder's posthumous name is "If^JLEIifc—SfbfcfiirlJ" (Kaiso Nikkyo Ichijo Daishi) in Japanese and "The Founder Nikkyo, Great Teacher of the One Vehicle" in English. -

Religion in the Age of Development

religions Article Religion in the Age of Development R. Michael Feener 1,* and Philip Fountain 2 1 Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, Marston Road, Oxford OX3 0EE, UK 2 Religious Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 20 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Religion has been profoundly reconfigured in the age of development. Over the past half century, we can trace broad transformations in the understandings and experiences of religion across traditions in communities in many parts of the world. In this paper, we delineate some of the specific ways in which ‘religion’ and ‘development’ interact and mutually inform each other with reference to case studies from Buddhist Thailand and Muslim Indonesia. These non-Christian cases from traditions outside contexts of major western nations provide windows on a complex, global history that considerably complicates what have come to be established narratives privileging the agency of major institutional players in the United States and the United Kingdom. In this way we seek to move discussions toward more conceptual and comparative reflections that can facilitate better understandings of the implications of contemporary entanglements of religion and development. Keywords: Religion; Development; Humanitarianism; Buddhism; Islam; Southeast Asia A Sarvodaya Shramadana work camp has proved to be the most effective means of destroying the inertia of any moribund village community and of evoking appreciation of its own inherent strength and directing it towards the objective of improving its own conditions. A.T. -

American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter

CHAPTER FO U R American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter ★ he Buddha’s Birthday is celebrated for weeks on end in Los Angeles. TMore than three hundred Buddhist temples sit in this great city fac- ing the Pacific, and every weekend for most of the month of May the Buddha’s Birthday is observed somewhere, by some group—the Viet- namese at a community college in Orange County, the Japanese at their temples in central Los Angeles, the pan-Buddhist Sangha Council at a Korean temple in downtown L.A. My introduction to the Buddha’s Birthday observance was at Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights, just east of Los Angeles. It is said to be the largest Buddhist temple in the Western hemisphere, built by Chinese Buddhists hailing originally from Taiwan and advocating a progressive Humanistic Buddhism dedicated to the pos- itive transformation of the world. In an upscale Los Angeles suburb with its malls, doughnut shops, and gas stations, I was about to pull over and ask for directions when the road curved up a hill, and suddenly there it was— an opulent red and gold cluster of sloping tile rooftops like a radiant vision from another world, completely dominating the vista. The ornamental gateway read “International Buddhist Progress Society,” the name under which the temple is incorporated, and I gazed up in amazement. This was in 1991, and I had never seen anything like it in America. The entrance took me first into the Bodhisattva Hall of gilded images and rich lacquerwork, where five of the great bodhisattvas of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition receive the prayers of the faithful. -

Chan Buddhism During the Times of Venerable Master Yixuan and Venerable Master Hsing Yun: Applying Chinese Chan Principles to Contemporary Society

《 》學報 ‧ 藝文│第三十二期 外文論文 Chan Buddhism During the Times of Venerable Master Yixuan and Venerable Master Hsing Yun: Applying Chinese Chan Principles to Contemporary Society Shi Juewei Director, Humanistic Buddhism Centre (Australia) Linji Venerable Master Yixuan 臨濟義玄 (d. 866) and Fo Guang Venerable Master Hsing Yun 佛光星雲1 (1927–), although separated by more than a millennium, innovatively applied Chan teachings to the societies in which they lived to help their devotees discover their humanity and transcend their existential conditions. Both religious leaders not only survived persecution, but brought their faiths to greater heights. This paper studies how these masters adapted Chan Buddhist teachings to the woes and conditions of their times. In particular, I shall review how Venerable Master Yixuan and Venerable Master Hsing Yun adapted the teachings of their predecessors, added value to the socio- political milieu of their times, and used familiar language to reconcile reality and their beliefs. Background These two Chan masters were selected because of the significance of their contributions. Venerable Master Yixuan was not only the founder of a popular 1. In the Pinyin system, the name should be expressed as Xingyun. In this paper, I use the more popular “Hsing Yun” instead. 170 Chan Buddhism During the Times of Venerable Master Yixuan and Venerable Master Hsing Yun: Applying Chinese Chan Principles to Contemporary Society Linji2 school in Chan Buddhism but was also posthumously awarded the title of Meditation Master of Wisdom Illumination (Huizhao Chanshi 慧照禪師)3 by Emperor Yizong 懿宗 of the Tang dynasty (r. 859–873). Venerable Master Hsing Yun, a strong proponent of Humanistic Buddhism, is the recipient of over 30 honorary doctoral degrees and honorary professorships from universities around the world.4 To have received such accolades, both Chan masters ought to have made momentous contribution to their societies. -

Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 2019 Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women" (2019). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 25. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Section Titles Placed Here | I Out of the Shadows Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU First Edition: Sri Satguru Publications 2006 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2019 Copyright © 2019 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover design Copyright © 2006 Allen Wynar Sakyadhita Conference Poster