Taiwan's Tzu Chi As Engaged Buddhism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Changes in Tzu Chi. by Yu-Shuang Yao and Richard Gombrich

Changes in Tzu Chi. By Yu-Shuang Yao and Richard Gombrich, October 2014. Tzu Chi will soon be fifty years old. Since 2010 it has been the subject of almost 300 graduate theses written in Taiwan, and that number will surely have increased before this paper is published.1 There has been widespread criticism of Tzu Chi for its lack of traditional Buddhist ritual and public observance of Buddhist festivals. Indeed, the movement has generally appeared somewhat austere in its lack of ritual and public spectacle, an austerity very much in the spirit of Tai Xu’s criticism of the Chinese Buddhism of his day. This year, on May 11th, Tzu Chi showed a new face to the world. The Buddha’s birthday (according to the Chinese Buddhist calendar) was celebrated in every branch of Tzu Chi worldwide. In Hualien the Master herself presided over a spectacular celebration involving, we estimate, nearly 2000 participants. These participants included the Tzu Chi nuns, who live in Hualien at the Abode, the movement’s headquarters; they normally lead reclusive lives and are not seen in public; so far as we can tell, this is the first time that they have taken part in any public ceremony. A similar ceremony was held on an even larger scale in Taipei at the Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall, and was observed by 300 members of the Buddhist Saṅgha who had been invited from around the world. This is the first time that representatives of other Buddhist movements, let alone ordained members of those movements, have been invited by Tzu Chi. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

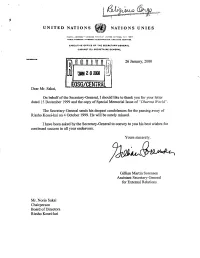

EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS ADRESSE POST ALE- UNITED NATIONS, N.V. 1OO17 CABLE AODflCSS ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: I/NATIONS NEWYORK EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL CABINET OU SECRETAIRE GENERAL REFERENCE: 26 January, 2000 EOSG/CENTRAL Dear Mr. Sakai, On behalf of the Secretary-General, I should like to thank you for your letter dated 15 December 1999 and the copy of Special Memorial Issue of "Dharma World". The Secretary-General sends his deepest condolences for the passing away of Rissho Kosei-kai on 4 October 1999. He will be surely missed. I have been asked by the Secretary-General to convey to you his best wishes for continued success hi all your endeavors. Yours sincerely, Gillian Martin Sorensen Assistant Secretary-General for External Relations Mr. Norio Sakai Chairperson Board of Directors Rissho Kosei-kai RISSHO KOSEI-KAI C, A BUDDHIST ORGANIZATION 2-11-1 Wada, Suginami-ku, Tokyo 166-8537, Japan, Tel: 03-3383-1111 lilJLU DEC 2 9 I999 December 15, 1999 Dear Sir/Madam, Special Memorial Issue of Dharrna World I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude for your friendship with Rissho Kosei-kai. As you may know, Founder Nikkyo Niwano peacefully passed away on October 4, 1999 at the age of 92. The enclosed Special Memorial Issue of Dharma World carries full details of the Founder's funeral ceremonies and a complete review of his life and work. I am very pleased to present this issue to you as a token of our wholehearted appreciation. Founder's posthumous name is "If^JLEIifc—SfbfcfiirlJ" (Kaiso Nikkyo Ichijo Daishi) in Japanese and "The Founder Nikkyo, Great Teacher of the One Vehicle" in English. -

Religion in the Age of Development

religions Article Religion in the Age of Development R. Michael Feener 1,* and Philip Fountain 2 1 Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, Marston Road, Oxford OX3 0EE, UK 2 Religious Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 20 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Religion has been profoundly reconfigured in the age of development. Over the past half century, we can trace broad transformations in the understandings and experiences of religion across traditions in communities in many parts of the world. In this paper, we delineate some of the specific ways in which ‘religion’ and ‘development’ interact and mutually inform each other with reference to case studies from Buddhist Thailand and Muslim Indonesia. These non-Christian cases from traditions outside contexts of major western nations provide windows on a complex, global history that considerably complicates what have come to be established narratives privileging the agency of major institutional players in the United States and the United Kingdom. In this way we seek to move discussions toward more conceptual and comparative reflections that can facilitate better understandings of the implications of contemporary entanglements of religion and development. Keywords: Religion; Development; Humanitarianism; Buddhism; Islam; Southeast Asia A Sarvodaya Shramadana work camp has proved to be the most effective means of destroying the inertia of any moribund village community and of evoking appreciation of its own inherent strength and directing it towards the objective of improving its own conditions. A.T. -

Overview of Actions Taken by Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation (BTCF)

Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation COVID-19 Relief Action Report #4 Overview of Actions taken by Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation (BTCF) As of 12 May, BTCF has: ● Distributed relief aid in 53 countries/regions (blue) with more distributions on the way for another 28 countries/regions (orange) ● A total of 14,466,805 items have been distributed with a further 7,440,677 items scheduled to be distributed ● Mid-term COVID-19 relief action plans have been initiated by BTCF chapters around the world including financial aid, material supplies and caring social support Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation COVID-19 Relief Action Report #4 Highlights by Region: Asia The Asia region, consisting of around 60% of the world’s population, is the most populated and diverse region in the world. Being the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries/regions in Asia experienced or are still experiencing severe lockdown restrictions. The cascading decline on local and national economy, along with lack of income and steep inflation of daily costs, have left our vulnerable communities struggling, wondering where their next meal may be. BTCF, founded in this region, has been supporting local Region Highlights communities for over half a century. Immediately, in early February, BTCF disaster management protocols were initiated and teams from different regions were dispatched to contact families Malaysia and individuals in our care. Understanding their needs, BTCF ● Care assistance for vulnerable communities. chapters quickly established suitable action plans and began the ● Long term partnerships paving the way for procurement of food supplies, necessities and personal protective COVID-19 co-operation. -

2019 Annual Report

TZU CHI USA Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation 2019 ANNUAL REPORT LETTER FROM THE CEO Wish All Living Beings Happiness and provided free medical care internationally, for 15,877 patients Freedom From Suffering in need in Ecuador and Mexico. As part of our long-term relief, we also rebuilt a church destroyed by the 2016 earthquake Tzu Chi USA, established in 1989, reached a major milestone in Ecuador and began reconstruction of the Morelos Institute in 2019, marking 30 years of service. Today, we have 66 offi ces destroyed in the 2017 earthquake in Mexico. in 25 states, with volunteers offering relief with compassion through Tzu Chi’s missions. Tzu Chi USA’s character education program continued to thrive in California and Texas. Implemented in eight schools, Addressing the needs of underserved populations and it provided 33,853 classes that reached 2,264 students. And, underprivileged families was at the forefront of our charity with the grand opening of the Tzu Chi Center in New York City mission in 2019. Our food pantry program helped families in in October, we now have a new home from which to inspire need across America, benefi ting 16,811 households, comprising care and compassion through exhibits that document Tzu Chi’s 109,688 individuals. In addition, our winter distributions humanitarian activities around the world. provided care to 2,608 individuals, offering $21,550 in cash cards, 1,116 eco-blankets & eco-scarves, and other essentials. We express our gratitude to all who supported Tzu Chi, and to all the agencies and organizations that partnered with us. -

DHARMA WORLD Vol3'

Cover photo: On March 5, Rissho Kosei May/June 2005 kai celebrated its 67th anniversary with a VoL3' ceremony in Fumon Hall in the organiza DHARMA WORLD tion's headquarters complex in Tokyo. Some 4,800 members took part in the For Living Buddhism and Interfaith Dialogue event, which was relayed by satellite TV to all branches throughout Japan, where simi lar ceremonies were held simultaneously. CONTENTS In Fumon Hall, forty members from young women's groups offered lighted candles and flowers. Photo: Yoshikazu Takekawa From the Advisor's Desk Reflections on the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Donate-a-Meal Campaign by Kinjiro Niwano 3 Essays Healing Our Suffering World by Cheng Yen 7 The Benefits of Haza Karma and Character: Fatalism or Free Will? DHARMA WORLD presents Buddhism as a Counseling Sessions 4 by I. Loganathan 17 practical living religion and promotes in terreligious dialogue for world peace. It The Emerging Euroyana by Michael Fuss 19 espouses views that emphasize the dignity The Real Purpose of Prayer by Kinzo Takemura 30 of life, seeks to rediscover our inner na ture and bring our lives more in accord with it, and investigates causes of human Reflections suffering. It tries to show how religious The Benefits of Hoza Counseling Sessions principles help solve problems in daily life by Nichiko Niwano 4 and how the least application of such The Precept Against Killing and principles has wholesome effects on the Acting Against Violence by Nikkyo Niwano 42 world around us. It seeks to demonstrate are fundamental to all reli truths that Healing Our Suffering World 7 gions, truths on which all people can act. -

Buddha-Nature, Critical Buddhism, and Early Chan*

Buddha-nature, Critical Buddhism, and Early Chan* Robert H. Sharf (University of California, Berkeley) 국문요약 이 논문은 불교와 서양 철학에 대한 최근의 비교 연구에서 왜 중세 중국불교 사상이 더 이목을 끌지 않았는지에 대한 반성으로 시작한다. 일본의 “비판 불 교”를 창시한 일본의 마츠모토 시로(松本史朗)와 하카마야 노리아키(袴谷憲 * This paper was originally prepared for the conference “Tathāgatagarbha or Buddha-nature Thought: Its Formation, Reception, and Transformation in India, East Asia, and Tibet,” held in Seoul, August 6-7, 2016. My thanks to the conference organizers and participants, as well as to the anonymous reviewers of this article, for their helpful feedback. Thanks also to Jay Garfield, Elizabeth Sharf, and Evan Thompson for their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts. 불교학리뷰 (Critical Review for Buddhist Studies) 22권 (2017. 12) 105p~150p 106 불교학리뷰 vol.22 昭)는 이러한 경시를 당연한 것으로 볼지 모른다. 그들은, 넓게는 동아시아불 교 전체, 좁게는 중국 선불교가 여래장과 불성사상을 수용하여 철학적으로 불 구가 되었다고 보기 때문이다. 실제로 마츠모토는 남종선의 설계자 중 한 사람 인 하택 신회(670-762)를 선종 입장에서 불성 이론을 옹호한 예로 뽑았다. 이 논문은 불성사상과 여래장사상이 실제로 비판적이고 철학적인 작업에 해로운지는 다루지 않는다. 오히려 이 논문의 관심은 8세기 남종선의 창시자 들이 가진 불성사상에 대한 깊은 관심은 그것을 수용하는 것과 전혀 무관하였 다는 것을 증명하는데 있다. 증거는 다음과 같다. (1) 신회의 저술, 주목할 만한 것은 그가 ‘무정불성’설에 대해 반대했다는 사실, (2) 육조단경, 특히 혜능 ‘오 도송’의 다양한 판본들이다. 그리하여 남종선은 비판불교학자들의 반-‘계일원 론(dhātuvāda)’에 대한 선구자로 간주할 수 있다. 이 논문은 중국불교 주석가들이 유가행파와 여래장의 형이상학적 일원론과 중관과 반야류 문헌의 반-실체론적 경향을 융합하려는데서 지속적으로 발생 하는 문제에 대한 평가로 마무리한다. -

Chinese Buddhist Moral Practices in Everyday Life: Dharma Drum Mountain, Volunteering and the Self

Chinese Buddhist Moral Practices in Everyday Life: Dharma Drum Mountain, Volunteering and the Self A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Social Science in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 Tsung-Han Yang School of Social Science Department of Sociology Table of Contents List of Tables…………………….............................................................9 Abstract ...................................................................................................10 Declaration……………………………………………………………...11 Copyright Statement…………………………………………………...11 Acknowledgements..................................................................................12 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………13 Introduction: Motivation For and Aims of the Thesis........................................13 Religion, Volunteering and Everyday Life………………………………………23 The Ethical Dimension of Everyday Life………………………………………..26 Religious Moral Habitus…………………………………………….……………27 The Sociological Perspective on Religious Moral Habitus……………………...28 Dharma Drum Mountain’s Chinese Buddhist Moral Habitus…………………...32 The Confucian View of Social Relationship and Morality ………………...….32 The Chinese Buddhist View of Social Relationships and Morality …………...34 Sheng Yen’s Notion of Character Education ………………………………….35 The Goal of Character Education…………………………………………..37 The Content of Character Education……………………………………….39 Summary of the thesis…………………………………………………………….40 2. An Introduction to Dharma Drum Mountain……………………..44 Introduction............................................................................................................44 -

Becoming a Disciple: the Recruiting Strategy of Tzu Chi

CHAPTER SIX BECOMING A DISCIPLE: THE RECRUITING STRATEGY OF TZU CHI Th is chapter discusses the recruitment strategies of the Tzu Chi Move- ment and the diff erent routes by which the members became involved in the Movement. Th e chapter has four main themes: 1. How the mem- bers came to know about Tzu Chi; 2. How the members fi rst encoun- tered Tzu Chi; 3. Th e routes to join Tzu Chi; 4. Some problems with joining more Tzu Chi. How the Members Came to Know about Tzu Chi Sociological research has shown that ‘person-to-person’ contact is one of the most important methods by which people get to know about NRMs (Wilson and Dobbelaere 1994: 59, 1987: 186; Barker E. 1898: 27). My research on Tzu Chi revealed a similar tendency. Initially most people became aware of the Movement through word of mouth, 15 per cent through the public media, and 9 per cent from Tzu Chi publica- tions (see Table 6.1). Th e majority of Tzu Chi members, then, learnt about the Movement through person to person contact. Th is suggests that Tzu Chi is a ‘com- munitarian group’ in the terms of Wilson and Dobbelaere. According to Wilson and Dobbelaere, one of the characteristics of such groups is that they put more emphasis on personal introductions and one to one contacts than on ‘large-scale rallies and collective occasions’ (Wilson and Dobbelaere 1994: 50). Table 6.1 How the public came to know about Tzu Chi Nos. Percentage of Survey Word of mouth 345 75% Public media 72 15% Tzu Chi publications 42 9% Total 459 99% 130 chapter six Some interviewees stated that they had heard of Tzu Chi from other Buddhist Masters.