VAX-11/780—A Virtual Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Memory

Chapter 4 Virtual Memory Linux processes execute in a virtual environment that makes it appear as if each process had the entire address space of the CPU available to itself. This virtual address space extends from address 0 all the way to the maximum address. On a 32-bit platform, such as IA-32, the maximum address is 232 − 1or0xffffffff. On a 64-bit platform, such as IA-64, this is 264 − 1or0xffffffffffffffff. While it is obviously convenient for a process to be able to access such a huge ad- dress space, there are really three distinct, but equally important, reasons for using virtual memory. 1. Resource virtualization. On a system with virtual memory, a process does not have to concern itself with the details of how much physical memory is available or which physical memory locations are already in use by some other process. In other words, virtual memory takes a limited physical resource (physical memory) and turns it into an infinite, or at least an abundant, resource (virtual memory). 2. Information isolation. Because each process runs in its own address space, it is not possible for one process to read data that belongs to another process. This improves security because it reduces the risk of one process being able to spy on another pro- cess and, e.g., steal a password. 3. Fault isolation. Processes with their own virtual address spaces cannot overwrite each other’s memory. This greatly reduces the risk of a failure in one process trig- gering a failure in another process. That is, when a process crashes, the problem is generally limited to that process alone and does not cause the entire machine to go down. -

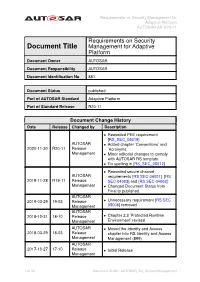

Requirements on Security Management for Adaptive Platform AUTOSAR AP R20-11

Requirements on Security Management for Adaptive Platform AUTOSAR AP R20-11 Requirements on Security Document Title Management for Adaptive Platform Document Owner AUTOSAR Document Responsibility AUTOSAR Document Identification No 881 Document Status published Part of AUTOSAR Standard Adaptive Platform Part of Standard Release R20-11 Document Change History Date Release Changed by Description • Reworded PEE requirement [RS_SEC_05019] AUTOSAR • Added chapter ’Conventions’ and 2020-11-30 R20-11 Release ’Acronyms’ Management • Minor editorial changes to comply with AUTOSAR RS template • Fix spelling in [RS_SEC_05012] • Reworded secure channel AUTOSAR requirements [RS SEC 04001], [RS 2019-11-28 R19-11 Release SEC 04003] and [RS SEC 04003] Management • Changed Document Status from Final to published AUTOSAR 2019-03-29 19-03 Release • Unnecessary requirement [RS SEC Management 05006] removed AUTOSAR 2018-10-31 18-10 Release • Chapter 2.3 ’Protected Runtime Management Environment’ revised AUTOSAR • Moved the Identity and Access 2018-03-29 18-03 Release chapter into RS Identity and Access Management Management (899) AUTOSAR 2017-10-27 17-10 Release • Initial Release Management 1 of 32 Document ID 881: AUTOSAR_RS_SecurityManagement Requirements on Security Management for Adaptive Platform AUTOSAR AP R20-11 Disclaimer This work (specification and/or software implementation) and the material contained in it, as released by AUTOSAR, is for the purpose of information only. AUTOSAR and the companies that have contributed to it shall not be liable for any use of the work. The material contained in this work is protected by copyright and other types of intel- lectual property rights. The commercial exploitation of the material contained in this work requires a license to such intellectual property rights. -

Programming Model, Address Mode, HC12 Hardware Introduction

EEL 4744C: Microprocessor Applications Lecture 2 Programming Model, Address Mode, HC12 Hardware Introduction Dr. Tao Li 1 Reading Assignment • Microcontrollers and Microcomputers: Chapter 3, Chapter 4 • Software and Hardware Engineering: Chapter 2 Or • Software and Hardware Engineering: Chapter 4 Plus • CPU12 Reference Manual: Chapter 3 • M68HC12B Family Data Sheet: Chapter 1, 2, 3, 4 Dr. Tao Li 2 EEL 4744C: Microprocessor Applications Lecture 2 Part 1 CPU Registers and Control Codes Dr. Tao Li 3 CPU Registers • Accumulators – Registers that accumulate answers, e.g. the A Register – Can work simultaneously as the source register for one operand and the destination register for ALU operations • General-purpose registers – Registers that hold data, work as source and destination register for data transfers and source for ALU operations • Doubled registers – An N-bit CPU in general uses N-bit data registers – Sometimes 2 of the N-bit registers are used together to double the number of bits, thus “doubled” registers Dr. Tao Li 4 CPU Registers (2) • Pointer registers – Registers that address memory by pointing to specific memory locations that hold the needed data – Contain memory addresses (without offset) • Stack pointer registers – Pointer registers dedicated to variable data and return address storage in subroutine calls • Index registers – Also used to address memory – An effective memory address is found by adding an offset to the content of the involved index register Dr. Tao Li 5 CPU Registers (3) • Segment registers – In some architectures, memory addressing requires that the physical address be specified in 2 parts • Segment part: specifies a memory page • Offset part: specifies a particular place in the page • Condition code registers – Also called flag or status registers – Hold condition code bits generated when instructions are executed, e.g. -

The Birth, Evolution and Future of Microprocessor

The Birth, Evolution and Future of Microprocessor Swetha Kogatam Computer Science Department San Jose State University San Jose, CA 95192 408-924-1000 [email protected] ABSTRACT timed sequence through the bus system to output devices such as The world's first microprocessor, the 4004, was co-developed by CRT Screens, networks, or printers. In some cases, the terms Busicom, a Japanese manufacturer of calculators, and Intel, a U.S. 'CPU' and 'microprocessor' are used interchangeably to denote the manufacturer of semiconductors. The basic architecture of 4004 same device. was developed in August 1969; a concrete plan for the 4004 The different ways in which microprocessors are categorized are: system was finalized in December 1969; and the first microprocessor was successfully developed in March 1971. a) CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computers) Microprocessors, which became the "technology to open up a new b) RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computers) era," brought two outstanding impacts, "power of intelligence" and "power of computing". First, microprocessors opened up a new a) VLIW(Very Long Instruction Word Computers) "era of programming" through replacing with software, the b) Super scalar processors hardwired logic based on IC's of the former "era of logic". At the same time, microprocessors allowed young engineers access to "power of computing" for the creative development of personal 2. BIRTH OF THE MICROPROCESSOR computers and computer games, which in turn led to growth in the In 1970, Intel introduced the first dynamic RAM, which increased software industry, and paved the way to the development of high- IC memory by a factor of four. -

IBM Z/Architecture Reference Summary

z/Architecture IBMr Reference Summary SA22-7871-06 . z/Architecture IBMr Reference Summary SA22-7871-06 Seventh Edition (August, 2010) This revision differs from the previous edition by containing instructions related to the facilities marked by a bar under “Facility” in “Preface” and minor corrections and clari- fications. Changes are indicated by a bar in the margin. References in this publication to IBM® products, programs, or services do not imply that IBM intends to make these available in all countries in which IBM operates. Any reference to an IBM program product in this publication is not intended to state or imply that only IBM’s program product may be used. Any functionally equivalent pro- gram may be used instead. Additional copies of this and other IBM publications may be ordered or downloaded from the IBM publications web site at http://www.ibm.com/support/documentation. Please direct any comments on the contents of this publication to: IBM Corporation Department E57 2455 South Road Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-5400 USA IBM may use or distribute whatever information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring any obligation to you. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2001-2010. All rights reserved. US Government Users Restricted Rights — Use, duplication, or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. ii z/Architecture Reference Summary Preface This publication is intended primarily for use by z/Architecture™ assembler-language application programmers. It contains basic machine information summarized from the IBM z/Architecture Principles of Operation, SA22-7832, about the zSeries™ proces- sors. It also contains frequently used information from IBM ESA/390 Common I/O- Device Commands and Self Description, SA22-7204, IBM System/370 Extended Architecture Interpretive Execution, SA22-7095, and IBM High Level Assembler for MVS & VM & VSE Language Reference, SC26-4940. -

Mi!!Lxlosalamos SCIENTIFIC LABORATORY

LA=8902-MS C3b ClC-l 4 REPORT COLLECTION REPRODUCTION COPY VAXNMS Benchmarking 1-’ > .— u) 9 g .— mi!!lxLOS ALAMOS SCIENTIFIC LABORATORY Post Office Box 1663 Los Alamos. New Mexico 87545 — wAifiimative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer b . l)lS(”L,\l\ll K “Thisreport wm prcpmd J, an xcttunt ,,1”wurk ,pmwrd by an dgmcy d the tlnitwl SIdtcs (kvcm. mm:. Ncit her t hc llniml SIJIL.. ( Lwcrnmcm nor any .gcncy tlhmd. nor my 08”Ihcif cmployccs. makci my wur,nly. mprcss w mphd. or JwImL.s m> lcg.d Iululity ur rcspmuhdily ltw Ilw w.cur- acy. .vmplctcncs. w uscftthtc>. ttt”any ml’ormdt ml. dpprdl us. prudu.i. w proccw didowd. or rep. resent%Ihd IIS us wuukl not mfrm$e priwtcly mvnd rqdtts. Itcl”crmcti herein 10 my sp.xi!l tom. mrcial ptotlucr. prtxcm. or S.rvskc hy tdc mmw. Irdcnmrl.. nmu(a.lurm. or dwrwi~.. does nut mmwsuily mnstitutc or reply its mdursmwnt. rccummcnddton. or favorin: by the llniwd States (“mvcmment ormy qxncy thctcd. rhc V!C$VSmd opinmm d .mthor% qmxd herein do nut net’. UMrily r;~lt or died lhow. ol”the llnttcd SIJIL.S( ;ovwnnwnt or my ugcncy lhure of. UNITED STATES .. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY CONTRACT W-7405 -ENG. 36 . ... LA-8902-MS UC-32 Issued: July 1981 G- . VAX/VMS Benchmarking Larry Creel —. I . .._- -- ----- ,. .- .-. .: .- ,.. .. ., ..,..: , .. .., . ... ..... - .-, ..:. .. *._–: - . VAX/VMS BENCHMARKING by Larry Creel ABSTRACT Primary emphasis in this report is on the perform- ance of three Digital Equipment Corporation VAX-11/780 computers at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Programs used in the study are part of the Laboratory’s set of benchmark programs. -

Virtual Memory - Paging

Virtual memory - Paging Johan Montelius KTH 2020 1 / 32 The process code heap (.text) data stack kernel 0x00000000 0xC0000000 0xffffffff Memory layout for a 32-bit Linux process 2 / 32 Segments - a could be solution Processes in virtual space Address translation by MMU (base and bounds) Physical memory 3 / 32 one problem Physical memory External fragmentation: free areas of free space that is hard to utilize. Solution: allocate larger segments ... internal fragmentation. 4 / 32 another problem virtual space used code We’re reserving physical memory that is not used. physical memory not used? 5 / 32 Let’s try again It’s easier to handle fixed size memory blocks. Can we map a process virtual space to a set of equal size blocks? An address is interpreted as a virtual page number (VPN) and an offset. 6 / 32 Remember the segmented MMU MMU exception no virtual addr. offset yes // < within bounds index + physical address segment table 7 / 32 The paging MMU MMU exception virtual addr. offset // VPN available ? + physical address page table 8 / 32 the MMU exception exception virtual address within bounds page available Segmentation Paging linear address physical address 9 / 32 a note on the x86 architecture The x86-32 architecture supports both segmentation and paging. A virtual address is translated to a linear address using a segmentation table. The linear address is then translated to a physical address by paging. Linux and Windows do not use use segmentation to separate code, data nor stack. The x86-64 (the 64-bit version of the x86 architecture) has dropped many features for segmentation. -

Virtual Memory in X86

Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 Virtual Memory in x86 Nima Honarmand Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 x86 Processor Modes • Real mode – walks and talks like a really old x86 chip • State at boot • 20-bit address space, direct physical memory access • 1 MB of usable memory • No paging • No user mode; processor has only one protection level • Protected mode – Standard 32-bit x86 mode • Combination of segmentation and paging • Privilege levels (separate user and kernel) • 32-bit virtual address • 32-bit physical address • 36-bit if Physical Address Extension (PAE) feature enabled Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 x86 Processor Modes • Long mode – 64-bit mode (aka amd64, x86_64, etc.) • Very similar to 32-bit mode (protected mode), but bigger address space • 48-bit virtual address space • 52-bit physical address space • Restricted segmentation use • Even more obscure modes we won’t discuss today xv6 uses protected mode w/o PAE (i.e., 32-bit virtual and physical addresses) Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 Virt. & Phys. Addr. Spaces in x86 Processor • Both RAM hand hardware devices (disk, Core NIC, etc.) connected to system bus • Mapped to different parts of the physical Virtual Addr address space by the BIOS MMU Data • You can talk to a device by performing Physical Addr read/write operations on its physical addresses Cache • Devices are free to interpret reads/writes in any way they want (driver knows) System Interconnect (Bus) : all addrs virtual DRAM Network … Disk (Memory) Card : all addrs physical Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 Virt-to-Phys Translation in x86 0xdeadbeef Segmentation 0x0eadbeef Paging 0x6eadbeef Virtual Address Linear Address Physical Address Protected/Long mode only • Segmentation cannot be disabled! • But can be made a no-op (a.k.a. -

Computer Organization

Chapter 12 Computer Organization Central Processing Unit (CPU) • Data section ‣ Receives data from and sends data to the main memory subsystem and I/O devices • Control section ‣ Issues the control signals to the data section and the other components of the computer system Figure 12.1 CPU Input Data Control Main Output device section section Memory device Bus Data flow Control CPU components • 16-bit memory address register (MAR) ‣ 8-bit MARA and 8-bit MARB • 8-bit memory data register (MDR) • 8-bit multiplexers ‣ AMux, CMux, MDRMux ‣ 0 on control line routes left input ‣ 1 on control line routes right input Control signals • Originate from the control section on the right (not shown in Figure 12.2) • Two kinds of control signals ‣ Clock signals end in “Ck” to load data into registers with a clock pulse ‣ Signals that do not end in “Ck” to set up the data flow before each clock pulse arrives 0 1 8 14 15 22 23 A IR T3 M1 0x00 0x01 2 3 9 10 16 17 24 25 LoadCk Figure 12.2 X T4 M2 0x02 0x03 4 5 11 18 19 26 27 5 C SP T1 T5 M3 0x04 0x08 5 6 7 12 13 20 21 28 29 B PC T2 T6 M4 0xFA 0xFC 5 30 31 A CPU registers M5 0xFE 0xFF CBus ABus BBus Bus MARB MARCk MARA MDRCk MDR MDRMux AMux AMux MDRMux CMux 4 ALU ALU CMux Cin Cout C CCk Mem V VCk ANDZ Addr ANDZ Z ZCk Zout 0 Data 0 0 0 N NCk MemWrite MemRead Figure 12.2 (Expanded) 0 1 8 14 15 22 23 A IR T3 M1 0x00 0x01 2 3 9 10 16 17 24 25 LoadCk X T4 M2 0x02 0x03 4 5 11 18 19 26 27 5 C SP T1 T5 M3 0x04 0x08 5 6 7 12 13 20 21 28 29 B PC T2 T6 M4 0xFA 0xFC 5 30 31 A CPU registers M5 0xFE 0xFF CBus ABus BBus -

Chapter 1: Microprocessor Architecture

Chapter 1: Microprocessor architecture ECE 3120 – Fall 2013 Dr. Mohamed Mahmoud http://iweb.tntech.edu/mmahmoud/ [email protected] Outline 1.1 Computer hardware organization 1.1.1 Number System 1.1.2 Computer hardware organization 1.2 The processor 1.3 Memory system operation 1.4 Program Execution 1.5 HCS12 Microcontroller 1.1.1 Number System - Computer hardware uses binary numbers to perform all operations. - Human beings are used to decimal number system. Conversion is often needed to convert numbers between the internal (binary) and external (decimal) representations. - Octal and hexadecimal numbers have shorter representations than the binary system. - The binary number system has two digits 0 and 1 - The octal number system uses eight digits 0 and 7 - The hexadecimal number system uses 16 digits: 0, 1, .., 9, A, B, C,.., F 1 - 1 - A prefix is used to indicate the base of a number. - Convert %01000101 to Hexadecimal = $45 because 0100 = 4 and 0101 = 5 - Computer needs to deal with signed and unsigned numbers - Two’s complement method is used to represent negative numbers - A number with its most significant bit set to 1 is negative, otherwise it is positive. 1 - 2 1- Unsigned number %1111 = 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 = 15 %0111 = 1 + 2 + 4 = 7 Unsigned N-bit number can have numbers from 0 to 2N-1 2- Signed number %1111 is a negative number. To convert to decimal, calculate the two’s complement The two’s complement = one’s complement +1 = %0000 + 1 =%0001 = 1 then %1111 = -1 %0111 is a positive number = 1 + 2 + 4 = 7. -

Virtual Memory

CSE 410: Systems Programming Virtual Memory Ethan Blanton Department of Computer Science and Engineering University at Buffalo Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References Virtual Memory Virtual memory is a mechanism by which a system divorces the address space in programs from the physical layout of memory. Virtual addresses are locations in program address space. Physical addresses are locations in actual hardware RAM. With virtual memory, the two need not be equal. © 2018 Ethan Blanton / CSE 410: Systems Programming Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References Process Layout As previously discussed: Every process has unmapped memory near NULL Processes may have access to the entire address space Each process is denied access to the memory used by other processes Some of these statements seem contradictory. Virtual memory is the mechanism by which this is accomplished. Every address in a process’s address space is a virtual address. © 2018 Ethan Blanton / CSE 410: Systems Programming Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References Physical Layout The physical layout of hardware RAM may vary significantly from machine to machine or platform to platform. Sometimes certain locations are restricted Devices may appear in the memory address space Different amounts of RAM may be present Historically, programs were aware of these restrictions. Today, virtual memory hides these details. The kernel must still be aware of physical layout. © 2018 Ethan Blanton / CSE 410: Systems Programming Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References The Memory Management Unit The Memory Management Unit (MMU) translates addresses. It uses a per-process mapping structure to transform virtual addresses into physical addresses. The MMU is physical hardware between the CPU and the memory bus. -

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 L/780

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 l/780 Joel S. Emer Douglas W. Clark Digital Equipment Corp. Digital Equipment Corp. 77 Reed Road 295 Foster Street Hudson, MA 01749 Littleton, MA 01460 ABSTRACT effect of many architectural and implementation features. This paper reports the results of a study of VAX- llR80 processor performance using a novel hardware Prior related work includes studies of opcode monitoring technique. A micro-PC histogram frequency and other features of instruction- monitor was buiit for these measurements. It kee s a processing [lo. 11,15,161; some studies report timing count of the number of microcode cycles execute z( at Information as well [l, 4,121. each microcode location. Measurement ex eriments were performed on live timesharing wor i loads as After describing our methods and workloads in well as on synthetic workloads of several types. The Section 2, we will re ort the frequencies of various histogram counts allow the calculation of the processor events in 5 ections 3 and 4. Section 5 frequency of various architectural events, such as the resents the complete, detailed timing results, and frequency of different types of opcodes and operand !!Iection 6 concludes the paper. specifiers, as well as the frequency of some im lementation-s ecific events, such as translation bu h er misses. ?phe measurement technique also yields the amount of processing time spent, in various 2. DEFINITIONS AND METHODS activities, such as ordinary microcode computation, memory management, and processor stalls of 2.1 VAX-l l/780 Structure different kinds. This paper reports in detail the amount of time the “average’ VAX instruction The llf780 processor is composed of two major spends in these activities.