Будућност Историје Музике the Future of Music History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Pavel Lisitsian Discography by Richard Kummins

Pavel Lisitsian Discography By Richard Kummins e-mail: [email protected] Rev - 17 June 2014 Composer Selection Other artists Date Lang Record # The capital city of the country (Stolitsa Agababov rodin) 1956 Rus 78 USSR 41366 (1956) LP Melodiya 14305/6 (1964) LP Melodiya M10 45467/8 (1984) CD Russian Disc 15022 (1994) MP3 RMG 1637 (2005 - Song Listen, maybe, Op 49 #2 (Paslushai, byt Anthology Vol 1) Arensky mozhet) Andrei Mitnik, piano 1951 Rus MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) 78 USSR 14626 (1947) LP Vocal Record Collector's Armenian (trad) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1947 Arm Society 1992 Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Crane (Groong) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Russian Folk Instrument Orchestra - Crane (Groong) Central TV and All-Union Radio LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) - Vladimir Fedoseyev 1968 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) LP DKS 6228 (1955) Armenian (trad) Dogwood forest (Lyut kizil usta tvoi) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1955 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Dream (Yeraz) (arranged by Aleksandr LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG -

Investigations Into the Zarlino-Galilei Dispute

WHERE NATURE AND ART ADJOIN: INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE ZARLINO- GALILEI DISPUTE, INCLUDING AN ANNOTATED TRANSLATION OF VINCENZO GALILEI’S DISCORSO INTORNO ALL’OPERE DI MESSER GIOSEFFO ZARLINO Randall E. Goldberg Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Jacobs School of Music Indiana University February 2011 UMI Number: 3449553 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3449553 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ____________________________ Thomas J. Mathiesen ____________________________ Massimo Ossi ____________________________ Ayana Smith ____________________________ Domenico Bertoloni Meli February 8, 2011 ii Copyright © 2011 Randall E. Goldberg iii Dedication For encouraging me to follow my dreams and helping me “be the ball,” this dissertation is dedicated with love to my parents Barry and Sherry Goldberg iv Acknowledgments There are many people and institutions that aided me in the completion of this project. First of all, I would like thank the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University. -

(English-Kreyol Dictionary). Educa Vision Inc., 7130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 713 FL 023 664 AUTHOR Vilsaint, Fequiere TITLE Diksyone Angle Kreyol (English-Kreyol Dictionary). PUB DATE 91 NOTE 294p. AVAILABLE FROM Educa Vision Inc., 7130 Cove Place, Temple Terrace, FL 33617. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Vocabularies /Classifications /Dictionaries (134) LANGUAGE English; Haitian Creole EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; Comparative Analysis; English; *Haitian Creole; *Phoneme Grapheme Correspondence; *Pronunciation; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *Bilingual Dictionaries ABSTRACT The English-to-Haitian Creole (HC) dictionary defines about 10,000 English words in common usage, and was intended to help improve communication between HC native speakers and the English-speaking community. An introduction, in both English and HC, details the origins and sources for the dictionary. Two additional preliminary sections provide information on HC phonetics and the alphabet and notes on pronunciation. The dictionary entries are arranged alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DIKSIONt 7f-ngigxrzyd Vilsaint tick VISION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDU ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS CENTER (ERIC) MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. \hkavt Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Points of view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES official OERI position or policy. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." 2 DIKSYCAlik 74)25fg _wczyd Vilsaint EDW. 'VDRON Diksyone Angle-Kreyal F. Vilsaint 1992 2 Copyright e 1991 by Fequiere Vilsaint All rights reserved. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

UTORAK, 17. April • TUESDAY April 17 ŽICE I DUŠA Strings & Soul

XI MEĐUNARODNI MUZIČKI FESTIVAL XI INTERNATIONAL MUSIC FESTIVAL ŽICE I DUŠA Strings & Soul PODGORICA 9–22 april 2012 UTORAK, 17. april • TUESDAY April 17 Velika scena CNP u 20h | Great Hall of MNT at 20 GUDAČKI KVARTET RUBIKON STRING QUARTET RUBICON [Crna Gora-Srbija • Montenegro-Serbia] Roman Simović Roman Simović violina | violin Miloš Petrović Miloš Petrović violina | violin Branko Kabadaić Branko Kabadaić viola | viola Dragan Đorđević Dragan Đorđević violončelo | violoncello PROGRAM • PROGRAMME ĐAKOMO PUČINI GIACOMO PUCCINI Crisantemi (Chrysanthemums) za gudački kvartet Crisantemi (Chrysanthemums) for String Quartet EDVARD ELGAR EDWARD ELGAR Gudački kvartet u e molu op. 83 String Quartet in e minor Op. 83 Allegro Moderato Piacevole (Pocco Andante) Allegro molto pauza • intermission TOŠIO HOSOKAVA TOSHIO HOSOKAWA Gudački kvartet „Cvjetanje” String Quartet “Blossoming” MORIS RAVEL MAURICE RAVEL Gudački kvartet u F-duru String Quartet in F Major Allegro Moderato Assez vif. Tres Rythme Tres lent Vif et agite Kažu da idealan sastav gudačkog kvarteta čine četiri muzičara sposobna za solističku karijeru koji dijele zajedničku ljubav prema literaturi kamerne muzike, a to je upravo ono što se može naći u kombinaciji ostvarenih i uspješnih gudača – violinista Romana Simovića i Miloša Petrovića, violiste, Branka Kabadaića, i čeliste Dragana Đorđevića – koji čine kvartet Rubikon. GUDAČKI KVARTET RUBIKON imao je prvi nastup 2003. na festivalu Grad Teatar u Budvi. Ubrzo je uslijedila turneja po Srbiji i Crnoj Gori a nakon toga, Rubikon kvartet je nastupio na festivalu Kotor Art. Kako je njihova reputacija rasla, kvaret je ubrzo pozvan od strane uvaženog violiniste/dirigenta Šlomo Minza da nastupi na prestižnom festivalu Sion-Vale, sa Hajekom Kazazianom i pijanistom Lajonelom Mo- neom. -

La Musique À La Renaissance Philippe Vendrix

La musique à la Renaissance Philippe Vendrix To cite this version: Philippe Vendrix. La musique à la Renaissance. Presses Universitaires de France, 127 p., 1999, Que sais-je ?, n. 3448. halshs-00008954 HAL Id: halshs-00008954 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00008954 Submitted on 19 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. La musique à la Renaissance Philippe Vendrix INTRODUCTION Chaque époque a construit des discours sur la musique, non pas pour réduire une pratique artistique à un ensemble de concepts, mais plutôt pour souligner le rôle central de l’art des sons dans les relations que l’être entretient avec la nature, avec le monde, avec l’univers, avec Dieu, et aussi avec sa propre imagination. Parler d’esthétique ou de théorie esthétique à la Renaissance peut paraître anachronique, du moins si l’on se réfère à la discipline philosophique qu’est l’esthétique, née effectivement au cours du XVIIIe siècle. Si l’on abandonne la notion héritée des Lumières pour plutôt s’interroger sur la réalité des prises de conscience esthétique, alors l’anachronisme n’est plus de mise. -

Arkivförteckning Rune Gustafssons Arkiv

Rune Gustafssons arkiv Svenskt visarkiv April 2013 Leif Larsson INLEDNING Rune Gustafsson ( 1933 – 2012 ) hörde sedan början av 1950-talet till en av Sveriges allra främsta jazzmusiker. Han började sin karriär hos trumslagaren Nils-Bertil Dahlander i Göteborg men flyttade några år senare till Stockholm. Under nästan hela fortsatta 1950-talet spelade han där tillsammans med Putte Wickman. Rune träffade 1959 Arne Domnérus som han sedan samarbetade med i många olika sammanhang. Under ett par årtionden var Rune Gustafsson en av våra mest anlitade studiomusiker som genom sin mångsidighet och flexibilitet passade in i de flesta situationer. Rune Gustafsson har bakom sig en rad egna skivor, bl. a. ”Move” som belönades med Orkesterjournalens Gyllene Skiva. Han har även varit involverad i flera andra produktioner som tilldelats denna utmärkelse. Under åren har RG samarbetat med en rad av jazzens internationella storheter, såsom Benny Carter, George Russel, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz och Zoot Sims. Med den sistnämnde gjorde Rune två skivor, den sista ”In A Sentimental Mood” kom att bli Zoot Sims allra sista. Med sin mångsidighet har Rune också varit efterfrågad i många andra musikaliska sammanhang, både i Sverige och stora delar av världen, t.ex. Eng- land, USA, Sydamerika, Ryssland, Japan och Kina. 1997 erhöll Rune det allra första priset ur Albin Hagströms minnesfond i Kungliga musikaliska akademien med motiveringen: ”För en mer än fyrtiofemårig gärning som framstående jazzsolist och mångsidig studio musiker – en beundrad förebild och outtömlig inspirationskälla för generationer svenska elgitarrister. 1998 fick Rune Gustafsson Thore Ehrlings stipendium med motiveringen: ”En av de mångsidigaste musikerna inom svensk populärmusik och vår genom tiderna främste jazzgitarrist”. -

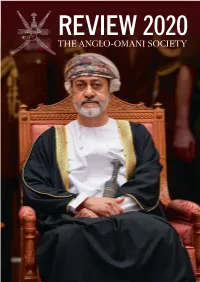

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

2009 SEM Honorary Member: Lois Ann Anderson Weapons of Mass In

Volume 44 Number 1 January 2010 curriculum. She directed the Ugandan 2009 SEM Honorary kiganda xylophone study group from Inside Member: Lois Ann 1975-2008 and she directed/coordi- 1 2009 SEM Honorary Member nated the Javanese gamelan ensem- 1 Weapons of Mass Instruction Anderson ble from 1976-1982. 3 People and Places Lois’s colleagues in musicology By Portia K. Maultsby, Virginia Gor- 4 nC embraced her vision for a broader 2 linski, and Mellonee Burnim 7 54th Annual Meeting curriculum and a more comprehen- 9 Prizes Lois Ann Anderson was among sive approach to the study of music 11 President’s Report the first generation of ethnomusicolo- traditions, integrating ethnomusicol- 13 Calls for Participation gists to graduate from UCLA and to ogy courses into the musicology 15 SEM Crossroads Project establish ethnomusicology programs program and including related content 15 Resolution of Thanks at major research institutions through- on PhD exams. The School of Music 17 Announcements out the country. After receiving her also adopted a more democratic 21 Conferences Calendar PhD under the directorship of Mantle administrative structure that rotated division chairs between the two disciplines. Over Weapons of Mass In- her forty years at the University of struction Wisconsin, Lois By Gage Averill, SEM President served as chair several times and “Ethnomusicology At the End Of she served as Di- Petroglobalization” rector of the Cen- You will notice as you attempt to ter for Southeast open up this edition of the Asian Studies Newslet- and spread it on the desk that it from 1981-1982. ter is no longer made of paper. -

KPFA Folio

KPFAFOLIO July 1%9 FM94.1 Ibnfcmt. vacaimt lit KPFA July Folio page 1 acDcfton, «r thcConfcquencct of Qo'^irrrin^ Troops .n h popuroui STt^tr^laTCd Town, taken f ., A KPFA 94.1 FM Listener Supported Radio 2207 Shattuck Avenue Berkeley, California 94704 -mil: Im Tel: (415) 848-6767 ^^^i station Manager Al Silbowitz Administrative Assistant . Marion Timofei Bookkeeper Erna Heims Assistant Bookkeeper .... Mariori Jansen Program Director . Elsa Knight Thompson Promotion Assistant Tom Green i Jean Jean Molyneaux News Director Lincoln Bergman Public Affairs Program Producer Denny Smithson Public Affairs Secretary .... Bobbie Harms Acting Drama & Literature Director Eleanor Sully Children's Programming Director Anne Hedley SKoAfS g«Lt>eHi'o»i Chief Engineer Ned Seagoon [ Engineering Assistants . Hercules Grytpype- thyne, Count Jim Moriarty Senior Production Assistant . Joe Agos . TVt^Hi ttoopj a*c4_ t'-vo-i-to-LS, Production Assistants . Bob Bergstresser Dana Cannon Traffic Clerk Janice Legnitto Subscription Lady Marcia Bartlett »,vJi u/fUyi^elM*^ e«j M"^ K/c> Receptionist Mildred Cheatham FOLIO Secretary Barbara Margolies ^k- »76I i^t^-c«4>v i-'},ooPi M.aAci.«<< The KPFA Folio Pt-lO«tO Hm.lr<^*'rSuLCjCJt4^\f*JL ' ' "a^ cLcC, u>*A C**t". JblooA. July, 1969 Volume20, No. 7 ®1969 Pacifica Foundation All Rights Reserved The KPFA FOLIO is published monthly and is dislributed free as a service to the subscribers of this listener-support- ed station. The FOLIO provides a detailed schedule of J^rx, Ojt-I itl- K«.A^ +Tajy4;^, UCfA programs broadcast A limited edition is published in braille. »J Dates after program listings indicate a repeat broadcast KPFA IS a non-commercial, educational radio station which broadcasts with 59.000 watts at 94 1 MH ly^onday through Fnday Broadcasting begins at 7:00 am, and on V livi tV.t«< weekends and holidays at 8 00 am Programming usually iV AA cUa«.>5 -rtvMUo WeJc.