CT 11 Final:Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Islamic Republic of Iran

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei’s writ dominates the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controls the armed forces and indirectly controls internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majlis. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviews all legislation the Majlis passes to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles; it also screens presidential and Majlis candidates for eligibility. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected president in June 2009 in a multiparty election that was generally considered neither free nor fair. There were numerous instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Demonstrations by opposition groups, university students, and others increased during the first few months of the year, inspired in part by events of the Arab Spring. In February hundreds of protesters throughout the country staged rallies to show solidarity with protesters in Tunisia and Egypt. The government responded harshly to protesters and critics, arresting, torturing, and prosecuting them for their dissent. As part of its crackdown, the government increased its oppression of media and the arts, arresting and imprisoning dozens of journalists, bloggers, poets, actors, filmmakers, and artists throughout the year. -

SEM 62 Annual Meeting

SEM 62nd Annual Meeting Denver, Colorado October 26 – 29, 2017 Hosted by University of Denver University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado College SEM 2017 Annual Meeting Table of Contents Sponsors .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Committees, Board, Staff, and Council ................................................................................................................................................... 2 – 3 Welcome Messages ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Exhibitors and Advertisers ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 – 7 Charles Seeger Lecture...................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Schedule at a Glance. ........................................................................................................................................................................................ -

(English-Kreyol Dictionary). Educa Vision Inc., 7130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 713 FL 023 664 AUTHOR Vilsaint, Fequiere TITLE Diksyone Angle Kreyol (English-Kreyol Dictionary). PUB DATE 91 NOTE 294p. AVAILABLE FROM Educa Vision Inc., 7130 Cove Place, Temple Terrace, FL 33617. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Vocabularies /Classifications /Dictionaries (134) LANGUAGE English; Haitian Creole EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; Comparative Analysis; English; *Haitian Creole; *Phoneme Grapheme Correspondence; *Pronunciation; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *Bilingual Dictionaries ABSTRACT The English-to-Haitian Creole (HC) dictionary defines about 10,000 English words in common usage, and was intended to help improve communication between HC native speakers and the English-speaking community. An introduction, in both English and HC, details the origins and sources for the dictionary. Two additional preliminary sections provide information on HC phonetics and the alphabet and notes on pronunciation. The dictionary entries are arranged alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DIKSIONt 7f-ngigxrzyd Vilsaint tick VISION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDU ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS CENTER (ERIC) MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. \hkavt Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Points of view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES official OERI position or policy. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." 2 DIKSYCAlik 74)25fg _wczyd Vilsaint EDW. 'VDRON Diksyone Angle-Kreyal F. Vilsaint 1992 2 Copyright e 1991 by Fequiere Vilsaint All rights reserved. -

Iran's Nuclear Ambitions From

IDENTITY AND LEGITIMACY: IRAN’S NUCLEAR AMBITIONS FROM NON- TRADITIONAL PERSPECTIVES Pupak Mohebali Doctor of Philosophy University of York Politics June 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the impact of Iranian elites’ conceptions of national identity on decisions affecting Iran's nuclear programme and the P5+1 nuclear negotiations. “Why has the development of an indigenous nuclear fuel cycle been portrayed as a unifying symbol of national identity in Iran, especially since 2002 following the revelation of clandestine nuclear activities”? This is the key research question that explores the Iranian political elites’ perspectives on nuclear policy actions. My main empirical data is elite interviews. Another valuable source of empirical data is a discourse analysis of Iranian leaders’ statements on various aspects of the nuclear programme. The major focus of the thesis is how the discourses of Iranian national identity have been influential in nuclear decision-making among the national elites. In this thesis, I examine Iranian national identity components, including Persian nationalism, Shia Islamic identity, Islamic Revolutionary ideology, and modernity and technological advancement. Traditional rationalist IR approaches, such as realism fail to explain how effective national identity is in the context of foreign policy decision-making. I thus discuss the connection between national identity, prestige and bargaining leverage using a social constructivist approach. According to constructivism, states’ cultures and identities are not established realities, but the outcomes of historical and social processes. The Iranian nuclear programme has a symbolic nature that mingles with socially constructed values. There is the need to look at Iran’s nuclear intentions not necessarily through the lens of a nuclear weapons programme, but rather through the regime’s overall nuclear aspirations. -

Iran 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Parliamentary elections held in 2016 and presidential elections held in 2017 were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

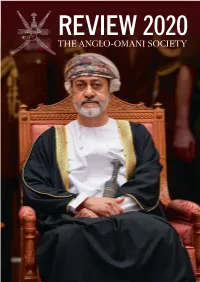

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

2009 SEM Honorary Member: Lois Ann Anderson Weapons of Mass In

Volume 44 Number 1 January 2010 curriculum. She directed the Ugandan 2009 SEM Honorary kiganda xylophone study group from Inside Member: Lois Ann 1975-2008 and she directed/coordi- 1 2009 SEM Honorary Member nated the Javanese gamelan ensem- 1 Weapons of Mass Instruction Anderson ble from 1976-1982. 3 People and Places Lois’s colleagues in musicology By Portia K. Maultsby, Virginia Gor- 4 nC embraced her vision for a broader 2 linski, and Mellonee Burnim 7 54th Annual Meeting curriculum and a more comprehen- 9 Prizes Lois Ann Anderson was among sive approach to the study of music 11 President’s Report the first generation of ethnomusicolo- traditions, integrating ethnomusicol- 13 Calls for Participation gists to graduate from UCLA and to ogy courses into the musicology 15 SEM Crossroads Project establish ethnomusicology programs program and including related content 15 Resolution of Thanks at major research institutions through- on PhD exams. The School of Music 17 Announcements out the country. After receiving her also adopted a more democratic 21 Conferences Calendar PhD under the directorship of Mantle administrative structure that rotated division chairs between the two disciplines. Over Weapons of Mass In- her forty years at the University of struction Wisconsin, Lois By Gage Averill, SEM President served as chair several times and “Ethnomusicology At the End Of she served as Di- Petroglobalization” rector of the Cen- You will notice as you attempt to ter for Southeast open up this edition of the Asian Studies Newslet- and spread it on the desk that it from 1981-1982. ter is no longer made of paper. -

Iran and the Gulf Military Balance - I

IRAN AND THE GULF MILITARY BALANCE - I The Conventional and Asymmetric Dimensions FIFTH WORKING DRAFT By Anthony H. Cordesman and Alexander Wilner Revised July 11, 2012 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Cordesman/Wilner: Iran & The Gulf Military Balance, Rev 5 7/11/12 2 Acknowledgements This analysis was made possible by a grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation. It draws on the work of Dr. Abdullah Toukan and a series of reports on Iran by Adam Seitz, a Senior Research Associate and Instructor, Middle East Studies, Marine Corps University. 2 Cordesman/Wilner: Iran & The Gulf Military Balance, Rev 5 7/11/12 3 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 5 THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 6 Figure III.1: Summary Chronology of US-Iranian Military Competition: 2000-2011 ............................... 8 CURRENT PATTERNS IN THE STRUCTURE OF US AND IRANIAN MILITARY COMPETITION ........................................... 13 DIFFERING NATIONAL PERSPECTIVES .............................................................................................................. 17 US Perceptions .................................................................................................................................... 17 Iranian Perceptions............................................................................................................................ -

Будућност Историје Музике the Future of Music History

Будућност историје музике The Future II/2019 of Music History 27 Реч уреднице Editor's Note ема броја 27 Будућност историје музике инспирисана је истоименим Тсеминаром, организованим у оквиру конференције одржане у Српској History академији наука и уметности септембра 2017. године. Организатор семинара био је Џим Самсон, један од најзначајнијих музиколога данашњице, емеритус професор колеџа Ројал Холовеј Универзитета у Лондону, редовни члан Британске Академије и аутор више од 100 Будућност публикација, међу којима је и прва обухватна историја музике на Балкану на енглеском језику (Music in the Balkans, Leiden: Brill, 2013). Проф. The Future Самсон је љубазно прихватио наш позив да буде гост-уредник овог броја часописа, у којем објављујемо радове четворо од петоро учесника панела историје Будућност историје музике (Рајнхарда Штрома, Мартина Лесера, Кетрин Елис и Марине Фролове-Вокер). Изражавамо велику захвалност овим еминентним музиколозима на исцрпном промишљању будућности музике музике наше дисциплине и настојањима да предмет изучавања постану географске регије, друштвени слојеви и слушалачке праксе који су досад били занемарени у музиколошким разматрањима. he theme of the issue No 27 The Future of Music History was inspired by the Teponymous seminar organised as part of a conference held at the Serbian The Future Academy of Sciences and Arts in September 2017. The seminar was prepared by Jim Samson, one of the most outstanding musicologists of our time, Emeritus Professor of Music, Royal Holloway (University of London), member of Music of the British Academy and author of more than 100 publications, including the first comprehensive history of music in the Balkans in English (Leiden: Brill, Будућност историје 2013). Professor Samson kindly accepted our invitation to be the guest editor History of this issue, in which we publish articles by four of the five panelists (Reinhard Strohm, Martin Loeser, Katharine Ellis and Marina Frolova-Walker). -

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

U.S. and Iranian Strategic Competition

Iran V: Sanctions Competition January 4, 2013 0 U.S. AND IRANIAN STRATEGIC COMPETITION Sanctions, Energy, Arms Control, and Regime Change Anthony H. Cordesman, Bryan Gold, Sam Khazai, and Bradley Bosserman April 19, 2013 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Note: This report is will be updated. Please provide comments and suggestions to [email protected] Iran V: Sanctions Competition April, 19 2013 I Executive Summary This report analyzes four key aspects of US and Iranian strategic competition - sanctions, energy, arms control, and regime change. Its primary focus is on the ways in which the sanctions applied to Iran have changed US and Iranian competition since the fall of 2011. This escalation has been spurred by the creation of a series of far stronger US unilateral sanctions and the EU‘s imposition of equally strong sanctions – both of which affect Iran‘s ability to export, its financial system and its overall economy. It has been spurred by Iran‘s ongoing missile deployments and nuclear program, as reported in sources like the November 2011 IAEA report that highlights the probable military dimensions of Iran‘s nuclear program. And, by Iranian rhetoric, by Iranian threats to ―close‖ the Gulf to oil traffic; increased support of the Quds Force and pro-Shiite governments and non-state actors; and by incidents like the Iranian-sponsored assassination plot against the Saudi Ambassador to the US, an Iranian government instigated mob attack on the British Embassy in Tehran on November 30, 2011, and the Iranian-linked attacks against Israeli diplomats. -

The Relationship Between the Supreme Leadership and Presidency and Its Impact on the Political System in Iran

Study The Relationship Between the Supreme Leadership and Presidency and Its Impact on the Political System in Iran By Dr. Motasem Sadiqallah | Researcher at the International Institute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah) Mahmoud Hamdi Abualqasim | Researcher at the International Insti- tute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah) www.rasanah-iiis.org WWW.RASANAH-IIIS.ORG Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 3 I- The Status and Role of the Supreme Leadership and the Presidency in the Iranian Political System ................................................................................. 4 II- The Problems Involving the Relationship Between the Supreme Leader and the Presidency .............................................................................................. 11 III- Applying Pressure Through Power to Dismiss the President .....................15 IV- The Implications of the Conflict Between the Supreme Leader and the Presidency on the Effectiveness of the Political System ................................. 20 V- The Future of the Relationship Between the Supreme Leader and the President ........................................................................................ 26 Conclusion .................................................................................................. 29 Disclaimer The study, including its analysis and views, solely reflects the opinions of the writers who are liable for the conclusions, statistics or mistakes contained therein