Iran 2012 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran Human Rights Defenders Report 2019/20

IRAN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS REPORT 2019/20 Table of Contents Definition of terms and concepts 4 Introduction 7 LAWYERS Amirsalar Davoudi 9 Payam Derafshan 10 Mohammad Najafi 11 Nasrin Sotoudeh 12 CIVIL ACTIVISTS Zartosht Ahmadi-Ragheb 13 Rezvaneh Ahmad-Khanbeigi 14 Shahnaz Akmali 15 Atena Daemi 16 Golrokh Ebrahimi-Irayi 17 Farhad Meysami 18 Narges Mohammadi 19 Mohammad Nourizad 20 Arsham Rezaii 21 Arash Sadeghi 22 Saeed Shirzad 23 Imam Ali Popular Student Relief Society 24 TEACHERS Esmaeil Abdi 26 Mahmoud Beheshti-Langroudi 27 Mohammad Habibi 28 MINORITY RIGHTS ACTIVISTS Mary Mohammadi 29 Zara Mohammadi 30 ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVISTS Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation 31 Workers rights ACTIVISTS Marzieh Amiri 32 This report has been prepared by Iran Human Rights (IHR) Esmaeil Bakhshi 33 Sepideh Gholiyan 34 Leila Hosseinzadeh 35 IHR is an independent non-partisan NGO based in Norway. Abolition of the Nasrin Javadi 36 death penalty, supporting human rights defenders and promoting the rule of law Asal Mohammadi 37 constitute the core of IHR’s activities. Neda Naji 38 Atefeh Rangriz 39 Design and layout: L Tarighi Hassan Saeedi 40 © Iran Human Rights, 2020 Rasoul Taleb-Moghaddam 41 WOMEN’S RIGHTS ACTIVISTS Raha Ahmadi 42 Raheleh Ahmadi 43 Monireh Arabshahi 44 Yasaman Aryani 45 Mojgan Keshavarz 46 Saba Kordafshari 47 Nedaye Zanan Iran 48 www.iranhr.net Recommendations 49 Endnotes 50 : @IHRights | : @iranhumanrights | : @humanrightsiran Definition of Terms & Concepts PRISONS Evin Prison: Iran’s most notorious prison where Wards 209, 240 and 241, which have solitary cells called security“suites” and are controlled by the Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS): Ward 209 Evin: dedicated to security prisoners under the jurisdiction of the MOIS. -

The Iranian Regime and the New Political Challenge

Foreign Policy Research Institute E-Notes A Catalyst for Ideas Distributed via Email and Posted at www.fpri.org June 2011 ~MIDDLE EAST MEDIA MONITOR~ AN ENEMY FROM WITHIN: THE IRANIAN REGIME AND THE NEW POLITICAL CHALLENGE By Raz Zimmt Middle East Media Monitor is an FPRI E-Note series, designed to review once a month a current topic from the perspective of the foreign language press in such countries as Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, and Turkey. These articles will focus on providing FPRI’s readership with an inside view on how some of the most important countries in the Middle East are covering issues of importance to the American foreign policy community. Raz Zimmt is a Ph.D. candidate in the Graduate School of Historical Studies and a research fellow at the Center for Iranian Studies at Tel Aviv University. He is the editor of the weekly “Spotlight on Iran,” published by the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, www.terrorism-info.org.il/site/home/default.asp . On May 11, 2011 hardliner cleric, Ayatollah Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi, held a meeting with members of the conservative Islamic Coalition Party. Mesbah-Yazdi warned his audience against the strengthening of deviant religious thought in Iranian society. He claimed that it jeopardizes the concept of “the Guardianship of the Islamic jurist” ( Velayat-e Faqih ), upon which the Iranian regime has been based since the Islamic Revolution (1979). “If this current continues and one day we will see another Seyyed Ali Mohammad Bab 1...we should not be surprised.” 2 A few days later, Ayatollah Seyyed Mohammad Sa’idi, the Friday prayer leader in Qom, warned the “deviant currents” to stop their conspiracies or the people will annihilate them, as they did to [Abolhassan] Banisadr, 3 “the hypocrites” [a reference to Iranian opposition organization, the Mojahedin-e Khalq ] and “the leaders of the sedition” [a reference to the reformist opposition]. -

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Islamic Republic of Iran

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei’s writ dominates the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controls the armed forces and indirectly controls internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majlis. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviews all legislation the Majlis passes to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles; it also screens presidential and Majlis candidates for eligibility. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected president in June 2009 in a multiparty election that was generally considered neither free nor fair. There were numerous instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Demonstrations by opposition groups, university students, and others increased during the first few months of the year, inspired in part by events of the Arab Spring. In February hundreds of protesters throughout the country staged rallies to show solidarity with protesters in Tunisia and Egypt. The government responded harshly to protesters and critics, arresting, torturing, and prosecuting them for their dissent. As part of its crackdown, the government increased its oppression of media and the arts, arresting and imprisoning dozens of journalists, bloggers, poets, actors, filmmakers, and artists throughout the year. -

En En Motion for a Resolution

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2009 - 2014 Plenary sitting 15.11.2011 B7-0598/2011 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION with request for inclusion in the agenda for the debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law pursuant to Rule 122 of the Rules of Procedure on Iran - recent cases of human rights violations Véronique De Keyser, María Muñiz De Urquiza, Kathleen Van Brempt, Pino Arlacchi, Corina Creţu, Kristian Vigenin on behalf of the S&D Group RE\P7_B(2011)0598_EN.doc PE472.810v01-00 EN United in diversityEN B7-0598/2011 European Parliament resolution on Iran - recent cases of human rights violations The European Parliament, - having regard to its previous resolutions on Iran, notably those concerning human rights and, in particular, those of February 2010 and January 2011, - having regard to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to all of which Iran is a party, - having regard to Rule 122(5) of its Rules of Procedure, A. whereas the multi-faceted human rights crisis is gripping Iran, including the persecution and prosecution of civil society actors, political activists, journalists, students, artists, lawyers, and environmental activists; as well as the routine denial of freedom of assembly, women’s rights, the rights of religious and ethnic minorities, and the skyrocketing rates of executions; B. whereas recent deaths of two human rights defenders, Haleh Sahabi and Hoda Saber, for which the officials were responsible, illustrate the existential threats to jailed human rights defenders and dissidents in Iran; C. -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

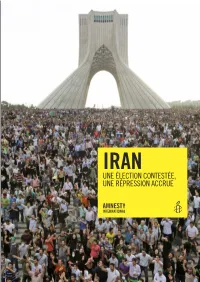

Iran. Une Élection Contestée, Une Répression Accrue

IRAN UNE ÉLECTION CONTESTÉE, UNE RÉPRESSION ACCRUE Amnesty International est un mouvement mondial regroupant 2,2 millions de personnes qui défendent les droits humains et luttent contre les atteintes à ces droits dans plus de 150 pays et territoires. La vision d’Amnesty International est celle d’un monde où chacun peut se prévaloir de tous les droits énoncés dans la Déclaration universelle des droits de l’homme et dans d’autres textes internationaux. Essentiellement financée par ses membres et les dons de particuliers, Amnesty International est indépendante de tout gouvernement, de toute tendance politique, de toute puissance économique et de toute croyance religieuse. Amnesty International Publications Publié pour la première fois en 2009 par Amnesty International Publications Secrétariat international Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street Londres WC1X 0DW Royaume-Uni www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2009 Index : MDE 13/123/2009 L’édition originale a été publiée en langue anglaise Imprimé par Amnesty International, Secrétariat international, Londres, Royaume-Uni Tous droits réservés. Cette publication, qui est protégée par le droit d'auteur, peut être reproduite gratuitement, par quelque procédé que ce soit, à des fins de sensibilisation, de campagne ou d'enseignement, mais pas à des fins commerciales. Les titulaires des droits d'auteur demandent à être informés de toute utilisation de ce document afin d’en évaluer l’impact. Toute reproduction dans d'autres circonstances, ou réutilisation dans d'autres publications, ou traduction, ou adaptation nécessitent l'autorisation écrite préalable des éditeurs, qui pourront exiger le paiement d'un droit. Photo de couverture : Des centaines de milliers de personnes manifestant sur Azadi (Place de la Liberté), à Téhéran, contre les résultats de l’élection présidentielle, le 15 juin 2009. -

PROTESTS and REGIME SUPPRESSION in POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY n OCTOBER 2020 n PN85 PROTESTS AND REGIME SUPPRESSION IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar Green Movement members tangle with Basij and police forces, 2009. he nationwide protests that engulfed Iran in late 2019 were ostensibly a response to a 50 percent gasoline price hike enacted by the administration of President Hassan Rouhani.1 But in little time, complaints Textended to a broader critique of the leadership. Moreover, beyond the specific reasons for the protests, they appeared to reveal a deeper reality about Iran, both before and since the 1979 emergence of the Islamic Republic: its character as an inherently “revolutionary country” and a “movement society.”2 Since its formation, the Islamic Republic has seen multiple cycles of protest and revolt, ranging from ethnic movements in the early 1980s to urban riots in the early 1990s, student unrest spanning 1999–2003, the Green Movement response to the 2009 election, and upheaval in December 2017–January 2018. The last of these instances, like the current round, began with a focus on economic dissatisfaction and then spread to broader issues. All these movements were put down by the regime with characteristic brutality. © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SAEID GOLKAR In tracking and comparing protest dynamics and market deregulation, currency devaluation, and the regime responses since 1979, this study reveals that cutting of subsidies. These policies, however, spurred unrest has become more significant in scale, as well massive inflation, greater inequality, and a spate of as more secularized and violent. -

2021 Year Ahead

2021 YEAR AHEAD Claudio Brocado Anthony Brocado January 29, 2021 1 2020 turned out to be quite unusual. What may the year ahead and beyond bring? As the year got started, the consensus was that a strong 2019 for equities would be followed by a positive first half, after which meaningful volatility would kick in due to the US presidential election. In the spirit of our prefer- ence for a contrarian stance, we had expected somewhat the opposite: some profit-taking in the first half of 2020, followed by a rally that would result in a positive balance at year-end. But in the way of the markets – which always tend to catch the largest number of participants off guard – we had what some would argue was one of the strangest years in recent memory. 2 2020 turned out to be a very eventful year. The global virus crisis (GVC) brought about by the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic was something no serious market observer had anticipated as 2020 got started. Volatility had been all but nonexistent early in what we call ‘the new 20s’, which had led us to expect the few remaining volatile asset classes, such as cryptocurrencies, to benefit from the search for more extreme price swings. We had expected volatilities across asset classes to show some convergence. The markets delivered, but not in the direction we had expected. Volatilities surged higher across many assets, with the CBOE volatility index (VIX) reaching some of the highest readings in many years. As it became clear that what was commonly called the novel coronavirus would bring about a pandemic as it spread to the remotest corners of the world at record speeds, the markets feared the worst. -

Download Report

Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy Report April 2014 smallmedia.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License INTRODUCTION // Despite the election of the moderate Hassan Rouhani to the presidency last year, Iran’s systematic filtering of online content and mobile phone apps continues at full-pace. In this month’s edition of the Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy Report, Small Media takes a closer look at one of the bodies most deeply-enmeshed with the process of overseeing and directing filtering policies - the ‘Commission to Determine the Instances of Criminal Content’ (or CDICC). This month’s report also tracks all the usual news about Iran’s filtering system, national Internet policy, and infrastructure development projects. As well as tracking high-profile splits in the estab- lishment over the filtering of the chat app WhatsApp, this month’s report also finds evidence that the government has begun to deploy the National Information Network (SHOMA), or ‘National Internet’, with millions of Iranians using it to access the government’s new online platform for managing social welfare and support. 2 THE COMMISSION TO DETERMINE THE INSTANCES OF CRIMINAL CONTENT (CDICC) THE COMMISSION TO DETERMINE THE INSTANCES OF CRIMINAL CONTENT (CDICC) overview The Commission to Determine the Instances of Criminal Content (CDICC) is the body tasked with monitoring cyberspace, and filtering criminal Internet content. It was established as a consequence of Iran’s Cyber Crime Law (CCL), which was passed by Iran’s Parliament in May 2009. According to Article 22 of the CCL, Iran’s Judiciary System was given the mandate of establishing CDICC under the authority of Iran’s Prosecutor’s Office. -

Iran and the Gulf Military Balance - I

IRAN AND THE GULF MILITARY BALANCE - I The Conventional and Asymmetric Dimensions FIFTH WORKING DRAFT By Anthony H. Cordesman and Alexander Wilner Revised July 11, 2012 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Cordesman/Wilner: Iran & The Gulf Military Balance, Rev 5 7/11/12 2 Acknowledgements This analysis was made possible by a grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation. It draws on the work of Dr. Abdullah Toukan and a series of reports on Iran by Adam Seitz, a Senior Research Associate and Instructor, Middle East Studies, Marine Corps University. 2 Cordesman/Wilner: Iran & The Gulf Military Balance, Rev 5 7/11/12 3 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 5 THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 6 Figure III.1: Summary Chronology of US-Iranian Military Competition: 2000-2011 ............................... 8 CURRENT PATTERNS IN THE STRUCTURE OF US AND IRANIAN MILITARY COMPETITION ........................................... 13 DIFFERING NATIONAL PERSPECTIVES .............................................................................................................. 17 US Perceptions .................................................................................................................................... 17 Iranian Perceptions............................................................................................................................ -

U.S. and Iranian Strategic Competition

Iran V: Sanctions Competition January 4, 2013 0 U.S. AND IRANIAN STRATEGIC COMPETITION Sanctions, Energy, Arms Control, and Regime Change Anthony H. Cordesman, Bryan Gold, Sam Khazai, and Bradley Bosserman April 19, 2013 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Note: This report is will be updated. Please provide comments and suggestions to [email protected] Iran V: Sanctions Competition April, 19 2013 I Executive Summary This report analyzes four key aspects of US and Iranian strategic competition - sanctions, energy, arms control, and regime change. Its primary focus is on the ways in which the sanctions applied to Iran have changed US and Iranian competition since the fall of 2011. This escalation has been spurred by the creation of a series of far stronger US unilateral sanctions and the EU‘s imposition of equally strong sanctions – both of which affect Iran‘s ability to export, its financial system and its overall economy. It has been spurred by Iran‘s ongoing missile deployments and nuclear program, as reported in sources like the November 2011 IAEA report that highlights the probable military dimensions of Iran‘s nuclear program. And, by Iranian rhetoric, by Iranian threats to ―close‖ the Gulf to oil traffic; increased support of the Quds Force and pro-Shiite governments and non-state actors; and by incidents like the Iranian-sponsored assassination plot against the Saudi Ambassador to the US, an Iranian government instigated mob attack on the British Embassy in Tehran on November 30, 2011, and the Iranian-linked attacks against Israeli diplomats. -

The Relationship Between the Supreme Leadership and Presidency and Its Impact on the Political System in Iran

Study The Relationship Between the Supreme Leadership and Presidency and Its Impact on the Political System in Iran By Dr. Motasem Sadiqallah | Researcher at the International Institute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah) Mahmoud Hamdi Abualqasim | Researcher at the International Insti- tute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah) www.rasanah-iiis.org WWW.RASANAH-IIIS.ORG Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 3 I- The Status and Role of the Supreme Leadership and the Presidency in the Iranian Political System ................................................................................. 4 II- The Problems Involving the Relationship Between the Supreme Leader and the Presidency .............................................................................................. 11 III- Applying Pressure Through Power to Dismiss the President .....................15 IV- The Implications of the Conflict Between the Supreme Leader and the Presidency on the Effectiveness of the Political System ................................. 20 V- The Future of the Relationship Between the Supreme Leader and the President ........................................................................................ 26 Conclusion .................................................................................................. 29 Disclaimer The study, including its analysis and views, solely reflects the opinions of the writers who are liable for the conclusions, statistics or mistakes contained therein