Translating Landscape: the Colombian Chorographic Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Última Voluntad Del Diputado Quiteño José Mexía De Lequerica1

ISSN 1696-0300 LA ÚLTIMA VOLUNTAD DEL DIPUTADO QUITEÑO JOSÉ MEXÍA DE LEQUERICA 1 Gloria de los Ángeles ZARZA RONDÓN Universidad de Cádiz RESUMEN: El artículo que presentamos pretende aclarar distintos datos historiográficos sobre la vida del diputado a Cortes por el Nuevo Reino de Granada, José Mexía de Lequerica. A través de la documentación consultada en los Archivos Históricos, Municipal y Provincial de Cádiz, además del Archivo Parroquial de San Antonio, hemos descubierto cuál fue su verdadera ubicación urbanística, con quiénes compartió el final de su vida, cuáles fueron sus últimas voluntades antes de fallecer, y cómo éstas se llevaron a cabo por sus albaceas testamentarios, ofreciendo así un panorama completo, y hasta ahora desconocido, sobre los últimos años de uno de los diputados hispanoamericanos más trascendentales del Cádiz doceañista. PALABRAS CLAVE: Protocolo notarial, Nuevo Reino de Granada, acta de defunción, padrón, Cortes de Cádiz. ABSTRACT: The article that we sense beforehand tries to clarify different information historiográficos on the life of the deputy to Spanish Parliament for the New Kingdom of Granada, Jose Mexía de Lequerica. Across the documentation consulted in the Historical, Municipal and Provincial Files of Cadiz, besides the Parochial File of San Antonio, we have discovered which was his real urban development location, with whom he shared the end of his life, which were his last wills before expiring, and how these were carried out by his testamentary executors, offering this way a complete panorama, and till now unknown, on the last years of one of the most transcendental Spanish-American deputies of the Cadiz doceañista. -

The Negritude Movements in Colombia

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses October 2018 THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA Carlos Valderrama University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Folklore Commons, Other Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Valderrama, Carlos, "THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1408. https://doi.org/10.7275/11944316.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1408 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA A Dissertation Presented by CARLOS ALBERTO VALDERRAMA RENTERÍA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SEPTEMBER 2018 Sociology © Copyright by Carlos Alberto Valderrama Rentería 2018 All Rights Reserved THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA A Dissertation Presented by CARLOS ALBERTO VALDERRAMA RENTERÍA Approved as to style and content by __________________________________________ Agustin Laó-Móntes, Chair __________________________________________ Enobong Hannah Branch, Member __________________________________________ Millie Thayer, Member _________________________________ John Bracey Jr., outside Member ______________________________ Anthony Paik, Department Head Department of Sociology DEDICATION To my wife, son (R.I.P), mother and siblings ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have finished this dissertation without the guidance and help of so many people. My mentor and friend Agustin Lao Montes. My beloved committee members, Millie Thayer, Enobong Hannah Branch and John Bracey. -

MCMANUS-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (4.095Mb)

The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McManus, Stuart Michael. 2016. The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493519 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World A dissertation presented by Stuart Michael McManus to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Stuart Michael McManus All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: James Hankins, Tamar Herzog Stuart Michael McManus The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World Abstract Historians have long recognized the symbiotic relationship between learned culture, urban life and Iberian expansion in the creation of “Latin” America out of the ruins of pre-Columbian polities, a process described most famously by Ángel Rama in his account of the “lettered city” (ciudad letrada). This dissertation argues that this was part of a larger global process in Latin America, Iberian Asia, Spanish North Africa, British North America and Europe. -

The Treatment of the Piano in Six Selected Chamber Works by Colombian Composers in the Twenty-First Century

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 The Treatment of the Piano in Six Selected Chamber Works by Colombian Composers in the Twenty-First Century Javier Camacho Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Camacho, Javier, "The Treatment of the Piano in Six Selected Chamber Works by Colombian Composers in the Twenty-First Century" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7067. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7067 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TREATMENT OF THE PIANO IN SIX SELECTED CHAMBER WORKS BY COLOMBIAN COMPOSERS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY Javier Camacho A Doctoral Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor -

Bambuco, Tango and Bolero: Music, Identity, and Class Struggles in Medell´In, Colombia, 1930–1953

BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 by Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado B.S. in Music (harpsichord), Ponti¯cia Universidad Javeriana, 1997 M.A. in Ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of Music in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2006 BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This dissertation explores the articulation of music, identity, and class struggles in the pro- duction, reception, and consumption of sound recordings of popular music in Colombia, 1930- 1953. I analyze practices of cultural consumption involving records in Medell¶³n,Colombia's second largest city and most important industrial center at the time. The study sheds light on some of the complex connections between two simultaneous historical processes during the mid-twentieth century, mass consumption and socio-political strife. Between 1930 and 1953, Colombian society experienced the rise of mass media and mass consumption as well as the outbreak of La Violencia, a turbulent period of social and political strife. Through an analysis of written material, especially the popular press, this work illustrates the use of aesthetic judgments to establish social di®erences in terms of ethnicity, social class, and gender. Another important aspect of the dissertation focuses on the adoption of music gen- res by di®erent groups, not only to demarcate di®erences at the local level, but as a means to inscribe these groups within larger imagined communities. -

Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes

Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Beatriz Goubert All rights reserved ABSTRACT Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Muiscas figure prominently in Colombian national historical accounts as a worthy and valuable indigenous culture, comparable to the Incas and Aztecs, but without their architectural grandeur. The magnificent goldsmith’s art locates them on a transnational level as part of the legend of El Dorado. Today, though the population is small, Muiscas are committed to cultural revitalization. The 19th century project of constructing the Colombian nation split the official Muisca history in two. A radical division was established between the illustrious indigenous past exemplified through Muisca culture as an advanced, but extinct civilization, and the assimilation politics established for the indigenous survivors, who were considered degraded subjects to be incorporated into the national project as regular citizens (mestizos). More than a century later, and supported in the 1991’s multicultural Colombian Constitution, the nation-state recognized the existence of five Muisca cabildos (indigenous governments) in the Bogotá Plateau, two in the capital city and three in nearby towns. As part of their legal battle for achieving recognition and maintaining it, these Muisca communities started a process of cultural revitalization focused on language, musical traditions, and healing practices. Today’s Muiscas incorporate references from the colonial archive, archeological collections, and scholars’ interpretations of these sources into their contemporary cultural practices. -

Introduction

Introduction A real cédula, addressed to the tribunal of accounts, or audit court, of Santa Fe de Bogotá on May 27, 1717, informed its members that Philip V, the first Bourbon king of Spain, had decided to create a new viceroyalty in northern South America. Other high-ranking civil and religious authorities across the region received similar documents communicating this decision. According to these documents, a number of “effective reasons of congruency” had convinced the king that it would be “most convenient” to appoint a viceroy to replace the president, governor and captain-general who had so far headed the audien- cia of Santa Fe.1 These documents further explained that the newly created viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada would comprise “the Province of Santa Fe, New Kingdom of Granada, [and] those of Cartagena, Santa Marta, Maracaibo, Caracas, Antioquia, Guyana, Popayan, and San Francisco de Quito”. The audiencia and tribunal of accounts based in Santa Fe became responsible for supervising the government and administration of all these territories to the exclusion of the courts in the viceroyalty of Peru and the audiencias of Santo Domingo, Panama and Quito.2 Thus, the first Bourbon king of Spain established the first new viceroyalty created within the Spanish Monarchy since the mid-sixteenth century. The viceroyalty, of course, was an administrative and political institution with a long tradition within the Spanish world. In 1701, when Philip V became king of Spain, the Spanish Monarchy included 10 such entities: Aragon, Catalonia, Navarre and Valencia within the Iberian Peninsula; Majorca, Naples, Sardinia and Sicily in the Mediterranean; and New Spain and Peru in the Americas. -

Art-Based Healing Strategies in Colombia in the Context of Collective Trauma: a Literature Review

ART-BASED HEALING STRATEGIES IN COLOMBIA IN THE CONTEXT OF COLLECTIVE TRAUMA: A LITERATURE REVIEW Ana María García Hernández A Research Paper in The Department of Creative Arts Therapies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2020 © ANA MARÍA GARCÍA HERNÁNDEZ 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This research paper prepared By: Ana María García Hernandez Entitled: Art-Based Healing Strategies in Colombia in the Context of Collective Trauma: A Literature Review and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Arts Therapies; Art Therapy Option) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality as approved by the research advisor. Research Advisor: ● s Janis Timm-Bottos, PhD, ATR-BC, PT Department Chair: Guylaine Vaillencourt, PhD, MTA April 2020 ABSTRACT ART-BASED HEALING STRATEGIES IN COLOMBIA IN THE CONTEXT OF COLLECTIVE TRAUMA: A LITERATURE REVIEW ANA MARÍA GARCÍA HERNÁNDEZ In Colombia, a country severely impacted by centuries of violence, many communities resorted to the use of art to overcome their collective trauma. The present research answers the question: “What is the existing literature that supports arts-based healing knowledge that has been developed in Colombia?” This research collects relevant data on the topic, gathered from professionals of different academic fields and reflects on it through an art therapy lens. Art-based healing strategies are reported in the literature associated with social and economic empowerment, reconnection of social fabric, transformation of social patterns and construction of hope. -

Scanned by Scan2net

CHIBCHA LEGENDS IN COLOMBIAN LITERATURE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN SPANISH IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF AR TS AND SCIENCES BY EDWINA TOOLEY MARTIN, B.A . DENTON, TEXAS MAY, 1962 Texas Woman's University University Hill Denton, Texas _________________________ May • _________________ 19 q_g__ __ W e hereby recommend that the thesis prepared under om supervision by -----'E'---'d"-'w"-'1=-· n=-=a ----"'T'--"o'--'o'-'l=-e=-y.,__c...cM-=a-=r-=t-=i'-'-n'-------- entitled Chibcha Legends in Colombian Literature be accepted as fulfilling this part of the requirements for the D egree of Master of Arts. Committee Chairman Accepted: ~f~ ... 1-80411 PREFACE La legende traduit les sentiments reels des peuples. Gustav Le Bon For centuries the golden treasure of the pre-conquest inhabitants of Colombia, South America, has captured man's imagination. The various legends of El DQrado led to the exploration of half of the South Am erican continent and the discovery of the Amazon River. It also lured Sir Walter Raleigh on the ill-fated expedition that finally cost him his head in the tower of London. These legends have inspired Colombia's men of letters and interested such foreign writers as Milton, Voltaire, and Andres/ Bello. Although it is true that the imaginative and psychological aspects of the legends are of particular interest to the student of a foreign culture, a legend may contain elements of historical truth also. Since these legends pro- vide insight into the early history of Colombia, an effort to find and preserve them has been made. -

Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 Maya Jiménez The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2151 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] COLOMBIAN ARTISTS IN PARIS, 1865-1905 by MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 © 2010 MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Katherine Manthorne____ _______________ _____________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Kevin Murphy__________ ______________ _____________________________ Date Executive Officer _______Professor Judy Sund________ ______Professor Edward J. Sullivan_____ ______Professor Emerita Sally Webster_______ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 by Maya A. Jiménez Adviser: Professor Katherine Manthorne This dissertation brings together a group of artists not previously studied collectively, within the broader context of both Colombian and Latin American artists in Paris. Taking into account their conditions of travel, as well as the precarious political and economic situation of Colombia at the turn of the twentieth century, this investigation exposes the ways in which government, politics and religion influenced the stylistic and thematic choices made by these artists abroad. -

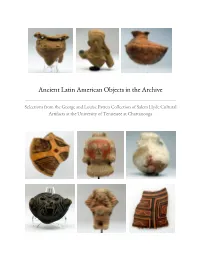

Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive

Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive Selections from the George and Louise Patten Collection of Salem Hyde Cultural Artifacts at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive: Selections from the George and Louise Patten Collection of Salem Hyde Cultural Artifacts at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga An exhibition catalog authored by students enrolled in Professor Caroline “Olivia” M. Wolf’s Latin American Visual Culture from Ancient to Modern class in Spring 2020. ● Heather Allen ● Abby Kandrach ● Rebekah Assid ● Casper Kittle ● Caitlin Ballone ● Jodi Koski ● Shaurie Bidot ● Anna Lee ● Katlynn Campbell ● Peter Li ● McKenzie Cleveland ● Sammy Mai ● Keturah Cole ● Amber McClane ● Kyle Cumberton ● Silvey McGregor ● Morgan Craig ● Brcien Partin ● Mallory Crook ● Kaitlyn Seahorn ● Nora Fernandez ● Cecily Salyer ● Briana Fitch ● Stephanie Swart ● Aaliyah Garnett ● Cameron Williams ● Hailey Gentry ● Lauren Williamson ● Riley Grisham ● Hannah Wimberly Lowe ● Chelsey Hall © 2020 by the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 5 A Collaborative Approach to Undergraduate Research 6 A Note on the Collection 7 Animal Figures 8 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Figure 10 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Monkey Figurine 11 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Sherd 12 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Bird-Shaped Whistle 13 Anthropomorphic Ceramics 14 Pre-Columbian Vessel Sherd 15 Pre-Columbian Handle Sherd 17 Pre-Columbian Panamanian Ceramic Vessel with Decorated -

Popular Royalists, Empire, and Politics in Southwestern New Granada, 1809 – 1819

Popular Royalists, Empire, and Politics in Southwestern New Granada, 1809 – 1819 Marcela Echeverri During the first decade of the nineteenth century, as Napoleon Bonaparte invaded the Iberian Peninsula, the Spanish monarchy entered into a transfor- mation unlike any other it had experienced since it claimed possession of the Americas. The replacement of King Fernando VII on the throne by Napoleon’s brother José in 1808 started a crisis of sovereignty felt from Madrid to Oaxaca to Tucumán, and all Spanish vassals were confronted with novel opportunities in the changing political landscape. In every corner of Spanish America, men and women faced the vacatio regis and adjusted to the liberal experiment taking form in the peninsula, as Spanish liberals unified to resist the French invasion. Their multiple and varied responses gave shape to anticolonial movements, in some cases, and in others were expressed through a renewed, full-fledged royalism. Since 1809 the Province of Popayán, encompassing the Pacific lowlands mining district and the Andean city of Pasto, had been a site of royalist resis- tance to the diverse autonomist and revolutionary projects that emerged in the viceroyalty of New Granada (colonial Colombia).1 Indians from the Pasto Research for this article was made possible by fellowships from New York University’s History Department, the John Carter Brown Library, and, in its final stages, through grants from Harvard’s Atlantic History Seminar and the Research Foundation of the City University of New York. Earlier versions of this work were presented at Harvard’s International Seminar on the History of the Atlantic World (August 2008), the Rutgers Center for Historical Analysis Seminar (October 2008), the City University of New York at Staten Island’s History Department Workshop (November 2008), and University of Texas Austin’s Institute for Historical Studies Independence and Decolonization Conference (April 2010).