Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paris, Brittany & Normandy

9 or 12 days PARIS, BRITTANY & NORMANDY FACULTY-LED INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS ABOUT THIS TOUR Rich in art, culture, fashion and history, France is an ideal setting for your students to finesse their language skills or admire the masterpieces in the Louvre. Delight in the culture of Paris, explore the rocky island commune of Mont Saint-Michel and reflect upon the events that took place during World War II on the beaches of Normandy. Through it all, you’ll return home prepared for whatever path lies ahead of you. Beyond photos and stories, new perspectives and glowing confidence, you’ll have something to carry with you for the rest of your life. It could be an inscription you read on the walls of a famous monument, or perhaps a joke you shared with another student from around the world. The fact is, there’s just something transformative about an EF College Study Tour, and it’s different for every traveler. Once you’ve traveled with us, you’ll know exactly what it is for you. DAY 2: Notre Dame DAY 3: Champs-Élysées DAY 4: Versailles DAY 5: Chartres Cathedral DAY 3: Taking in the views from the Eiff el Tower PARIS, BRITTANY & NORMANDY 9 or 12 days Rouen Normandy (2) INCLUDED ON TOUR: OPTIONAL EXCURSION: Mont Saint-Michel Caen Paris (4) St. Malo (1) Round-trip airfare Versailles Chartres Land transportation Optional excursions let you incorporate additional Hotel accommodations sites and attractions into your itinerary and make the Light breakfast daily and select meals most of your time abroad. Full-time Tour Director Sightseeing tours and visits to special attractions Free time to study and explore EXTENSION: French Riviera (3 days) FOR MORE INFORMATION: Extend your tour and enjoy extra time exploring your efcollegestudytours.com/FRAA destination or seeing a new place at a great value. -

Human Values of Colombian People. Evidence for the Functionalist Theory of Values

Human values of colombian people. Evidence for the functionalist theory of values Human values of colombian people. Evidence for the functionalist theoryof values Valores Humanos de los Colombianos. Evidencia de la Teoría Funcionalista de los Valores Recibido: Febrero de 201228 de mayo de 2010. Rubén Ardila Revisado: Agosto de 20124 de junio de 2012. National University of Colombia, Colombia Aceptado: Octubre de 2012 Valdiney V. Gouveia Universidad Federal de Paraíba, Brasil Emerson Diógenes de Medeiros Universidad Federal de Piauí, Brasil This paper was supported in part by grant of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development to the second author. Authors are grateful to this agency. Correspondence must be addressed to Rubén Ardila, National University of Colombia. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Resumen The objective of this research work has been to get to El objetivo de esta investigación ha sido conocer la orientación know the axiological orientation of Colombians, and axiológica de los colombianos, y reunir evidencias empíricas gather empirical evidence regarding the suitability of the con respecto a la adecuación de la teoría funcionalista de functionalist theory of values in Colombia, testing its content los valores en Colombia, comprobando sus hipótesis de and structure hypothesis and the psychometric properties contenido y estructura y las propiedades psicométricas de of its measurement (Basic Values Questionnaire BVQ). The su medida (el Cuestionario de Valores Básicos, CVB). El BVQ evaluates sexuality, success, social support, knowledge, CVB evalúa sexualidad, éxito, apoyo social, conocimiento, emotion, power, affection, religiosity, health, pleasure, emoción, poder, afectividad, religiosidad, salud, placer, prestige, obedience, personal stability, belonging, beauty, prestigio, obediencia, estabilidad personal, pertenencia, tradition, survival, and maturity. -

Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano

COLOMBIAN NATIONALISM: FOUR MUSICAL PERSPECTIVES FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO by Ana Maria Trujillo A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music The University of Memphis December 2011 ABSTRACT Trujillo, Ana Maria. DMA. The University of Memphis. December/2011. Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano. Dr. Kenneth Kreitner, Ph.D. This paper explores the Colombian nationalistic musical movement, which was born as a search for identity that various composers undertook in order to discover the roots of Colombian musical folklore. These roots, while distinct, have all played a significant part in the formation of the culture that gave birth to a unified national identity. It is this identity that acts as a recurring motif throughout the works of the four composers mentioned in this study, each representing a different stage of the nationalistic movement according to their respective generations, backgrounds, and ideological postures. The idea of universalism and the integration of a national identity into the sphere of the Western musical tradition is a dilemma that has caused internal struggle and strife among generations of musicians and artists in general. This paper strives to open a new path in the research of nationalistic music for violin and piano through the analyses of four works written for this type of chamber ensemble: the third movement of the Sonata Op. 7 No.1 for Violin and Piano by Guillermo Uribe Holguín; Lopeziana, piece for Violin and Piano by Adolfo Mejía; Sonata for Violin and Piano No.3 by Luís Antonio Escobar; and Dúo rapsódico con aires de currulao for Violin and Piano by Andrés Posada. -

![HIS 105-[Section], Latin American Fiction and History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8818/his-105-section-latin-american-fiction-and-history-278818.webp)

HIS 105-[Section], Latin American Fiction and History

1 HIS 105-04 Latin American Fiction and History Professor Willie Hiatt, Spring 2010 MWF • 8-8:50 a.m. • Clough Hall 300 OFFICE: Clough Hall 311 OFFICE HOURS: 9-11 a.m. Monday and Wednesday; 1-3 p.m. Tuesday; and by appointment PHONE: Office: 901-843-3656; Cell: 859-285-7037 E-MAIL: [email protected] COURSE OVERVIEW This introduction to Latin American history exposes you to broad literary, social, and cultural currents in the modern period, roughly covering independence from Spain to today. You will analyze novels, short stories, poetry, and plays as historical documents that illuminate national identity, race, gender, class, and politics at specific historical moments. The course engages costumbrismo, modernism, vanguardism, indigenismo, magical realism, and other literary and historical currents from Mexico and the Caribbean in the north to the Andes and Argentina in the south. You will address a number of important questions: How can we read fictional texts as historical documents? How does fiction expand our knowledge of Latin America’s colonial and postcolonial past? What does literature tells us about the region that no other historical documents do? And what does writing across culture and language mean for modern identity and national authenticity? The course covers a number of important themes: Colonial Legacies and Republican Possibilities Nation-Building Civilization vs. Barbarism Cultural Emancipation Liberalism vs. Conservatism Indigenismo (a political, intellectual, and artistic project that defended indigenous masses against exploitation) Imperialism Magical Realism 2 COURSE READINGS You may purchase required books at the Rhodes College bookstore or at local and online retailers. -

Site/Non-Site Explores the Relationship Between the Two Genres Which the Master of Aix-En- Provence Cultivated with the Same Passion: Landscapes and Still Lifes

site / non-site CÉZANNE site / non-site Guillermo Solana Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid February 4 – May 18, 2014 Fundación Colección Acknowledgements Thyssen-Bornemisza Board of Trustees President The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Hervé Irien José Ignacio Wert Ortega wishes to thank the following people Philipp Kaiser who have contributed decisively with Samuel Keller Vice-President their collaboration to making this Brian Kennedy Baroness Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza exhibition a reality: Udo Kittelmann Board Members María Alonso Perrine Le Blan HRH the Infanta Doña Pilar de Irina Antonova Ellen Lee Borbón Richard Armstrong Arnold L. Lehman José María Lassalle Ruiz László Baán Christophe Leribault Fernando Benzo Sáinz Mr. and Mrs. Barron U. Kidd Marina Loshak Marta Fernández Currás Graham W. J. Beal Glenn D. Lowry HIRH Archduchess Francesca von Christoph Becker Akiko Mabuchi Habsburg-Lothringen Jean-Yves Marin Miguel Klingenberg Richard Benefield Fred Bidwell Marc Mayer Miguel Satrústegui Gil-Delgado Mary G. Morton Isidre Fainé Casas Daniel Birnbaum Nathalie Bondil Pia Müller-Tamm Rodrigo de Rato y Figaredo Isabella Nilsson María de Corral López-Dóriga Michael Brand Thomas P. Campbell Nils Ohlsen Artistic Director Michael Clarke Eriko Osaka Guillermo Solana Caroline Collier Nicholas Penny Marcus Dekiert Ann Philbin Managing Director Lionel Pissarro Evelio Acevedo Philipp Demandt Jean Edmonson Christine Poullain Secretary Bernard Fibicher Earl A. Powell III Carmen Castañón Jiménez Gerhard Finckh HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco Giancarlo Forestieri William Robinson Honorary Director Marsha Rojas Tomàs Llorens David Franklin Matthias Frehner Alejandra Rossetti Peter Frei Katy Rothkopf Isabel García-Comas Klaus Albrecht Schröder María García Yelo Dieter Schwarz Léonard Gianadda Sir Nicholas Serota Karin van Gilst Esperanza Sobrino Belén Giráldez Nancy Spector Claudine Godts Maija Tanninen-Mattila Ann Goldstein Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza Michael Govan Charles L. -

1856 2 Jean Baptiste Du Tertre, “Indigoterie”

iLLusTRaTions Plates (Appear after page 204) 1 Anonymous, Johnny Heke (i.e., Hone Heke), 1856 2 Jean Baptiste Du Tertre, “Indigoterie” (detail), 1667 3 Anonymous, The Awakening of the Third Estate, 1789 4 José Campeche, El niño Juan Pantaleón de Avilés de Luna, 1808 5 William Blake, God Writing on the Tablets of the Covenant, 1805 6 James Sawkins, St. Jago [i.e., Santiago de] Cuba, 1859 7 Camille Pissarro, The Hermitage at Pontoise, 1867 8 Francisco Oller y Cestero, El Velorio [The Wake], 1895 9 Cover of Paris-Match 10 Bubbles scene from Rachida, 2002 11 Still of Ofelia from Pan’s Labyrinth, 2006 figures 1 Marie- Françoise Plissart from Droit de regards, 1985 2 2 Jean-Baptiste du Tertre, “Indigoterie,” Histoire générale des Antilles Habitées par les François, 1667 36 3 Plan of the Battle of Waterloo 37 4 John Bachmann, Panorama of the Seat of War: Bird’s Eye View of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and the District of Columbia, 1861 38 Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/chapter-pdf/651991/9780822393726-ix.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 5 “Multiplex set” from FM- 30–21 Aerial Photography: Military Applications, 1944 39 6 Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, Master Sergeant Steve Horton, U.S. Air Force 40 7 Anonymous, Toussaint L’Ouverture, ca. 1800 42 8 Dupuis, La Chute en masse, 1793 43 9 Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Untitled [Slaves, J. J. Smith’s Plantation near Beaufort, South Carolina], 1862 44 10 Emilio Longoni, May 1 or The Orator of the Strike, 1891 45 11 Ben H’midi and Ali la Pointe from The Battle of Algiers, 1966 46 12 An Inconvenient Truth, 2006 47 13 “Overseer,” detail from Du Tertre, “Indigoterie” 53 14 Anthony Van Dyck, Charles I at the Hunt, ca. -

La Constitución De Rionegro Antecedentes Y Esfuerzos

LA CONSTITUCIÓN DE RIONEGRO ANTECEDENTES Y ESFUERZOS EN LA CONCRECIÓN DE UN SISTEMA POLÍTICO PARA COLOMBIA THE CONSTITUTION OF RIONEGRO BACKGROUND AND EFFORTS IN CONCRETION OF A POLITICAL SYSTEM FOR COLOMBIA LA CONSTITUTION DE RIONEGRO CONTEXTE ET LES EFFORTS EN CONCRÉTION D’UN SYSTÈME POLITIQUE POUR LA COLOMBIE Fecha de recepción: 24 de mayo de 2015 Fecha de aprobación: 16 de junio de 2015 Jorge Enrique Patiño-Rojas1 221 1 Magíster en historia, Magíster en Economía de la Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. Docente Investigador Universitario Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. Avenida Central del Norte 39-115, 150003 Tunja, Tunja, Boyacá Revista Principia Iuris, ISSN Impreso 0124-2067 / ISSN En línea 2463-2007 Julio-Diciembre 2015, Vol. 12, No. 24 - Págs. 221 - 239 LA CONSTITUCIÓN DE RIONEGRO, ANTECEDENTES Y ESFUERZOS EN LA CONCRECIÓN DE UN SISTEMA POLÍTICO PARA COLOMBIA Resumen En este artículo nos referimos a los antecedentes de la Carta de Rionegro y sus aportes a la configuración de un sistema político para Colombia, en particular su contribución al significativo reparto del poder en el territorio de la antigua Nueva Granada por ella generado. El texto incluye de manera somera, y solo como análogos antecedentes, las características generales de la organización política territorial de la Civilización Chibcha y la estructura político-administrativa del Estado en la época colonial. No obstante, previo a abordar la materia objeto de examen, se hace necesario tratar dos temas importantes: uno forzoso, que provee el marco conceptual para el desarrollo del texto, y el otro referido tanto a las figuras más sobresalientes de los epónimos constituyentes de 1863, como a las instituciones democráticas de más avanzada en aquella Constitución. -

Stephen A. Cruikshank

THE MULATA AFFECT: BIOREMEDIATION IN THE CUBAN ARTS by Stephen A. Cruikshank A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in SPANISH AND LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES Department of Modern Languages and Cultural Studies University of Alberta © Stephen A. Cruikshank, 2018 ii Abstract The "mulata affect" may be understood as the repetitive process and movement of power and affect qualified in the mulata image over time. Through a lens of affect theory this study seeks to analyse how the mulata image in Cuba has historically been affected by, and likewise affected, cultural expressions and artistic representations. Relying on a theory of "bioremediation" this study proposes that the racialized body of the mulata, which is remediated through artistic images, consistently holds the potential to affect both national and exotic interpretations of her body and of Cuban culture. Four different artistic expressions of the mulata image are discussed. Beginning in the early twentieth century various artistic mediums are explored in the contexts of the mulata in the paintings of Carlos Enríquez's and the rumbera [rumba dancer] in the graphic illustrations of Conrado Massaguer. In addition, images of the miliciana [the militant woman] in the photography of Alberto Korda following the onset of Cuban Revolution and the jinetera [the sex-worker] in Daniel Díaz Torres film La película de Ana (2012) are discussed. Through an analysis of these four different expressions of the mulata body, this study seeks to expose a genealogy of the mulata image in art and, in doing so, reveal the ongoing visual changes and affective workings of the racialized female body that has contributed to the designations of Cuban culture and identity over time. -

NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012

ISSUE 8 NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012 Plans are moving ahead for the 2012 MAC AGM which is to be held in Trinidad, October 21st-24th. For further information please regularly visit the MAC website. Over the last 6 months whilst compiling articles for the newsletter one positive thing that has struck the Secretariat is the increase in the promotion Inside This Issue of information exchange in the Caribbean region. The newsletter has covered a range of conferences occurring this year throughout the Caribbean and 2. Caribbean: Crossroads of several new publications on curatorship in the Caribbean will have been the World Exhibition released by the end of 2012. 3. World Heritage Inscription Ceremony in Barbados Museums and museum staff should make the most of these conferences and 4. Zoology Inspired Art see them not only as a forum to learn about new practices but also as a way 5. 2012 MAC AGM to meet colleagues, not necessarily just in the field of museum work but also 6. New Book Released in many other disciplines. In the present financial situation the world finds ´&XUDWLQJLQWKH&DULEEHDQµ 7. Sint Marteen National itself, it may sound odd to be promoting attendance at conferences and Heritage Foundation buying books but museums must promote continued professional 8. ICOM Advisory Committee development of their staff - if not they will stagnate and the museum will Meeting suffer. 9. Membership Form 10. Association of Caribbean MAC is of course aware that the financial constraints facing many museums at Historians Conference present may limit the physical attendance at conferences. -

Constitución De 1863

CONSTITUCIÓN DE 1863 La constitución de 1863 es la que surge como resultado de las guerra, en que se reprimen al partido conservador, que había sido derrotado por el grupo de los liberales, es así como surgen los “Estados Unidos de Colombia “ y así se llamó la constitución de 1863 o constitución de Rionegro, de corte liberal y federalista, conformado por nueve estados soberanos (Panamá, Antioquia, Magdalena, Bolívar, Santander, Boyacá, Cundinamarca, Tolima y Cauca), bajo la mirada incisiva de Tomas Cipriano de Mosquera, quien decretaría la ley de amortización de bienes de manos muertas. A partir de ese momento el gobierno nacional queda dividido en los tres poderes que aun hoy sobreviven, el ejecutivo, legislativo y judicial, con un periodo para el Presidente de la Unión de dos años, en tanto que los presidentes de los estados tenían un mandato de cuatro, el presidente debía ser elegido por los votos que cada estado habría depositado, este proceso dependía de cada estado si bien en algunos no se presentaba ninguna restricción, otros mantenían la imposibilidad de votar para los que no supieran leer y escribir y poseer propiedad; se prohibió la reelección para todos los casos; se liberó el porte y comercio de armas; se propendió por el impulso económico y por el fortalecimiento de los estados en detrimento del estado central, lo que conllevo a rivalidades e intereses y al surgimiento de figuras como Manuel Antonio Caro y Rafael Núñez, quienes darían paso a un nuevo orden centralista a partir de los años 80 conduciendo a la promulgación de la constitución de 1886. -

ALEJANDRO OTERO B. 1921, El Manteco, Venezuela D. 1990

ALEJANDRO OTERO b. 1921, El Manteco, Venezuela d. 1990, Caracas, Venezuela SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2019 Alejandro Otero: Rhythm in Line and Space, Sicardi Ayers Bacino, Houston, TX, USA 2017 Kinesthesia: Latin American Kinetic Art, 1954–1969 - Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Spring, CA 2016 Kazuya Sakai - Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City MOLAA at twenty: 1996-2016 - Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA), Long Beach, CA 2015 Moderno: Design for Living in Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, 1940–1978 - The Americas Society Art Gallery, New York City, NY 2014 Impulse, Reason, Sense, Conflict. - CIFO - Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, Miami, FL 2013 Donald Judd+Alejandro Otero - Galería Cayón, Madrid Obra en Papel - Universidad Metropolitana, Caracas Intersections - MOLAA Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, CA Mixtape - MOLAA Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, CA Concrete Inventions. Patricia Phelp de Cisneros Collection - Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. 2012 O Espaço Ressoante Os Coloritmos De Alejandro Otero - Instituto de Arte Contemporânea (IAC), São Paulo, Brazil Constellations: Constructivism, Internationalism, and the Inter-American Avant-Garde - AMA Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC Caribbean: Crossroads Of The World - El Museo del Barrio, the Queens Museum of Art & The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York City, NY 2011 Arte latinoamericano 1910 - 2010 - MALBA Colección Costantini - Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires 2007 Abra Solar. Un camino hacia la luz. Centro de Arte La Estancia, Caracas, Venezuela 2006 The Rhythm of Color: Alejandro Otero and Willys de Castro: Two Modern Masters in the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection - Fundación Cisneros. The Aspen Institute, Colorado Exchange of glances: Visions on Latin America. -

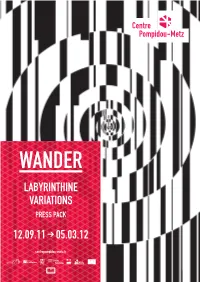

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN .......................................................................................