Runes a Book of Runes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Norse Mythology — Comparative Perspectives Old Norse Mythology— Comparative Perspectives

Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature No. 3 OLd NOrse MythOLOgy — COMParative PersPeCtives OLd NOrse MythOLOgy— COMParative PersPeCtives edited by Pernille hermann, stephen a. Mitchell, and Jens Peter schjødt with amber J. rose Published by THE MILMAN PARRY COLLECTION OF ORAL LITERATURE Harvard University Distributed by HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2017 Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives Published by The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Distributed by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England Copyright © 2017 The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature All rights reserved The Ilex Foundation (ilexfoundation.org) and the Center for Hellenic Studies (chs.harvard.edu) provided generous fnancial and production support for the publication of this book. Editorial Team of the Milman Parry Collection Managing Editors: Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy Executive Editors: Casey Dué and David Elmer Production Team of the Center for Hellenic Studies Production Manager for Publications: Jill Curry Robbins Web Producer: Noel Spencer Cover Design: Joni Godlove Production: Kristin Murphy Romano Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hermann, Pernille, editor. Title: Old Norse mythology--comparative perspectives / edited by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, Jens Peter Schjødt, with Amber J. Rose. Description: Cambridge, MA : Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, 2017. | Series: Publications of the Milman Parry collection of oral literature ; no. 3 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2017030125 | ISBN 9780674975699 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mythology, Norse. | Scandinavia--Religion--History. Classifcation: LCC BL860 .O55 2017 | DDC 293/.13--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030125 Table of Contents Series Foreword ................................................... -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

The Carian Language HANDBOOK of ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE the NEAR and MIDDLE EAST

The Carian Language HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-SIX The Carian Language by Ignacio J. Adiego with an appendix by Koray Konuk BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adiego Lajara, Ignacio-Javier. The Carian language / by Ignacio J. Adiego ; with an appendix by Koray Konuk. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 86). Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13 : 978-90-04-15281-6 (hardback) ISBN-10 : 90-04-15281-4 (hardback) 1. Carian language. 2. Carian language—Writing. 3. Inscriptions, Carian—Egypt. 4. Inscriptions, Carian—Turkey—Caria. I. Title. II. P946.A35 2006 491’.998—dc22 2006051655 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 15281 4 ISBN-13 978 90 04 15281 6 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Hotei Publishers, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

University of London Deviant Burials in Viking-Age

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA Ruth Lydia Taylor M. Phil, Institute of Archaeology, University College London UMI Number: U602472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602472 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA The thesis brings together information yielded from archaeology and other sources to provide an overall picture of the types of burial practices encountered during the Viking-Age in Scandinavia. From this, an attempt is made to establish deviancy. Comparative evidence, such as literary, runic, legal and folkloric evidence will be used critically to shed perspective on burial practices and the artefacts found within the graves. The thesis will mostly cover burials from the Viking Age (late 8th century to the mid- 11th century), but where the comparative evidence dates from other periods, its validity is discussed accordingly. Two types of deviant burial emerged: the criminal and the victim. A third type, which shows distinctive irregularity yet lacks deviancy, is the healer/witch burial. -

Proposal to Encode 0D5F MALAYALAM LETTER ARCHAIC II

Proposal to encode 0D5F MALAYALAM LETTER ARCHAIC II Shriramana Sharma, jamadagni-at-gmail-dot-com, India 2012-May-22 §1. Introduction In the Malayalam Unicode encoding, the independent letter form for the long vowel Ī is: ഈ where the length mark ◌ൗ is appended to the short vowel ഇ to parallel the symbols for U/UU i.e. ഉ/ഊ. However, Ī was originally written as: As these are entirely different representations of Ī, although their sound value may be the same, it is proposed to encode the archaic form as a separate character. §2. Background As the core Unicode encoding for the major Indic scripts is based on ISCII, and the ISCII code chart for Malayalam only contained the modern form for the independent Ī [1, p 24]: … thus it is this written form that came to be encoded as 0D08 MALAYALAM LETTER II. While this “new” written form is seen in print as early as 1936 CE [2]: … there is no doubt that the much earlier form was parallel to the modern Grantha , both of which are derived from the old Grantha Ī as seen below: 1 ma - īdṛgvidhā | tatarāya īṇ Old Grantha from the Iḷaiyānputtūr copper plates [3, p 13]. Also seen is the Vatteḻuttu Ī of the same time (line 2, 2nd char from right) which also exhibits the two dots. Of course, both are derived from old South Indian Brahmi Ī which again has the two dots. It is said [entire paragraph: Radhakrishna Warrier, personal communication] that it was the poet Vaḷḷattōḷ Nārāyaṇa Mēnōn (1878–1958) who introduced the new form of Ī ഈ. -

Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W

Knowl. Org. 46(2019)No.3 209 W. Korwin and H. Lund. Alphabetization Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W. Dunedin Rd., Columbus, OH 43214, USA, <[email protected]> **University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies, DK-2300 Copenhagen S Denmark, <[email protected]> Wendy Korwin received her PhD in American studies from the College of William and Mary in 2017 with a dissertation entitled Material Literacy: Alphabets, Bodies, and Consumer Culture. She has worked as both a librarian and an archivist, and is currently based in Columbus, Ohio, United States. Haakon Lund is Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies in Denmark. He is educated as a librarian (MLSc) from the Royal School of Library and Information Science, and his research includes research data management, system usability and users, and gaze interaction. He has pre- sented his research at international conferences and published several journal articles. Korwin, Wendy and Haakon Lund. 2019. “Alphabetization.” Knowledge Organization 46(3): 209-222. 62 references. DOI:10.5771/0943-7444-2019-3-209. Abstract: The article provides definitions of alphabetization and related concepts and traces its historical devel- opment and challenges, covering analog as well as digital media. It introduces basic principles as well as standards, norms, and guidelines. The function of alphabetization is considered and related to alternatives such as system- atic arrangement or classification. Received: 18 February 2019; Revised: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 21 March 2019 Keywords: order, orders, lettering, alphabetization, arrangement † Derived from the article of similar title in the ISKO Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization Version 1.0; published 2019-01-10. -

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

MA ritgerð Norræn trú Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell Október 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell 60 einingar Félags– og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október, 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA-gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Caroline Elizabeth Oxley, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Caroline Oxley MA in Old Nordic Religion: Thesis Kennitala: 181291-3899 Október 2019 Abstract Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum: Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view This thesis is a study of animal shape-shifting in Old Norse culture, considering, among other things, the related concepts of hamr, hugr, and the fylgjur (and variations on these concepts) as well as how shape-shifters appear to be associated with the wild, exile, immorality, and violence. Whether human, deities, or some other type of species, the shape-shifter can be categorized as an ambiguous and fluid figure who breaks down many typical societal borderlines including those relating to gender, biology, animal/ human, and sexual orientation. As a whole, this research project seeks to better understand the background, nature, and identity of these figures, in part by approaching the subject psychoanalytically, more specifically within the framework established by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, as part of his theory of archetypes. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

The Origin of the Alphabet: an Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis

Colless, Brian E. The origin of the alphabet: an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 12, 2014 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Colless, Brian E. “The origin of the alphabet : an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis” [en línea], Antiguo Oriente : Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente 12 (2014). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/origin-alphabet-goldwasser-hypothesis.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] . 03 Colless - Alphabet_Antiguo Oriente 09/06/2015 10:22 a.m. Página 71 THE ORIGIN OF THE ALPHABET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE GOLDWASSER HYPOTHESIS BRIAN E. COLLESS [email protected] Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Summary: The Origin of the Alphabet Since 2006 the discussion of the origin of the Semitic alphabet has been given an impetus through a hypothesis propagated by Orly Goldwasser: the alphabet was allegedly invented in the 19th century BCE by illiterate Semitic workers in the Egyptian turquoise mines of Sinai; they saw the picturesque Egyptian inscriptions on the site and borrowed a number of the hieroglyphs to write their own language, using a supposedly new method which is now known by the technical term acrophony. The main weakness of the theory is that it ignores the West Semitic acrophonic syllabary, which already existed, and contained most of the letters of the alphabet. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Anglo-Saxon Runes

Runes Each rune can mean something in divination (fortune telling) but they also act as a phonetic alphabet. This means that they can sound out words. When writing your name or whatever in runes, don’t pay attention to the letters we use, but rather the sounds we use to make up the words. Then finds the runes with the closest sounds and put them together. Anglo- Swedo- Roman Germanic Danish Saxon Norwegian A ansuz ac ar or god oak-tree (?) AE aesch ash-tree A/O or B berkanan bercon or birch-twig (?) C cen torch D dagaz day E ehwaz horse EA ear earth, grave(?) F fehu feoh fe fe money, cattle, money, money, money, wealth property property property gyfu / G gebo geofu gift gift (?) G gar spear H hagalaz hail hagol (?) I isa is iss ice ice ice Ï The sound of this character was something ihwaz / close to, but not exactly eihwaz like I or IE. yew-tree J jera year, fruitful part of the year K kenaz calc torch, flame (?) (?) K name unknown L laguz / laukaz water / fertility M mannaz man N naudiz need, necessity, nou (?) extremity ing NG ingwaz the god the god "Ing" "Ing" O othala- hereditary land, oethil possession OE P perth-(?) peorth meaning unclear (?) R raidho reth (?) riding, carriage S sowilo sun or sol (?) or sun tiwaz / teiwaz T the god Tiw (whose name survives in Tyr "Tuesday") TH thurisaz thorn thurs giant, monster (?) thorn giant, monster U uruz ur wild ox (?) wild ox W wunjo joy X Y yr bow (?) Z agiz(?) meaning unclear Now write your name: _________________________________________________________________ Rune table borrowed from: www.cratchit.org/dleigh/alpha/runes/runes.htm . -

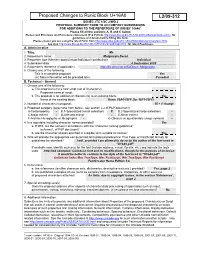

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4.