Orthographies in Early Modern Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Norse Mythology — Comparative Perspectives Old Norse Mythology— Comparative Perspectives

Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature No. 3 OLd NOrse MythOLOgy — COMParative PersPeCtives OLd NOrse MythOLOgy— COMParative PersPeCtives edited by Pernille hermann, stephen a. Mitchell, and Jens Peter schjødt with amber J. rose Published by THE MILMAN PARRY COLLECTION OF ORAL LITERATURE Harvard University Distributed by HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2017 Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives Published by The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Distributed by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England Copyright © 2017 The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature All rights reserved The Ilex Foundation (ilexfoundation.org) and the Center for Hellenic Studies (chs.harvard.edu) provided generous fnancial and production support for the publication of this book. Editorial Team of the Milman Parry Collection Managing Editors: Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy Executive Editors: Casey Dué and David Elmer Production Team of the Center for Hellenic Studies Production Manager for Publications: Jill Curry Robbins Web Producer: Noel Spencer Cover Design: Joni Godlove Production: Kristin Murphy Romano Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hermann, Pernille, editor. Title: Old Norse mythology--comparative perspectives / edited by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, Jens Peter Schjødt, with Amber J. Rose. Description: Cambridge, MA : Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, 2017. | Series: Publications of the Milman Parry collection of oral literature ; no. 3 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2017030125 | ISBN 9780674975699 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mythology, Norse. | Scandinavia--Religion--History. Classifcation: LCC BL860 .O55 2017 | DDC 293/.13--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030125 Table of Contents Series Foreword ................................................... -

Romanian Language and Its Dialects

Social Sciences ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS Ana-Maria DUDĂU1 ABSTRACT: THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE, THE CONTINUANCE OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE SPOKEN IN THE EASTERN PARTS OF THE FORMER ROMAN EMPIRE, COMES WITH ITS FOUR DIALECTS: DACO- ROMANIAN, AROMANIAN, MEGLENO-ROMANIAN AND ISTRO-ROMANIAN TO COMPLETE THE EUROPEAN LINGUISTIC PALETTE. THE ROMANIAN LINGUISTS HAVE ALWAYS SHOWN A PERMANENT CONCERN FOR BOTH THE IDENTITY AND THE STATUS OF THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS, THUS SUPPORTING THE EXISTENCE OF THE ETHNIC, LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL PARTICULARITIES OF THE MINORITIES AND REJECTING, FIRMLY, ANY ATTEMPT TO ASSIMILATE THEM BY FORCE KEYWORDS: MULTILINGUALISM, DIALECT, ASSIMILATION, OFFICIAL LANGUAGE, SPOKEN LANGUAGE. The Romanian language - the only Romance language in Eastern Europe - is an "island" of Latinity in a mainly "Slavic sea" - including its dialects from the south of the Danube – Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian. Multilingualism is defined narrowly as the alternative use of several languages; widely, it is use of several alternative language systems, regardless of their status: different languages, dialects of the same language or even varieties of the same idiom, being a natural consequence of linguistic contact. Multilingualism is an Europe value and a shared commitment, with particular importance for initial education, lifelong learning, employment, justice, freedom and security. Romanian language, with its four dialects - Daco-Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno- Romanian and Istro-Romanian – is the continuance of the Latin language spoken in the eastern parts of the former Roman Empire. Together with the Dalmatian language (now extinct) and central and southern Italian dialects, is part of the Apenino-Balkan group of Romance languages, different from theAlpine–Pyrenean group2. -

Ebook Download a Reference Grammar of Modern Italian

A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF MODERN ITALIAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Maiden,Cecilia Robustelli | 512 pages | 01 Jun 2009 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780340913390 | Italian | London, United Kingdom A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian PDF Book This Italian reference grammar provides a comprehensive, accessible and jargon-free guide to the forms and structures of Italian. This rule is not absolute, and some exceptions do exist. Parli inglese? Italian is an official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries' populations. The rediscovery of Dante's De vulgari eloquentia , as well as a renewed interest in linguistics in the 16th century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language. Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian has many inconsistent outcomes, where the same underlying sound produces different results in different words, e. An instance of neuter gender also exists in pronouns of the third person singular. Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to that continent. This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Retrieved 7 August Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to being a phonemic orthography. For a group composed of boys and girls, ragazzi is the plural, suggesting that -i is a general plural. Book is in Used-Good condition. Story of Language. A history of Western society. It formerly had official status in Albania , Malta , Monaco , Montenegro Kotor , Greece Ionian Islands and Dodecanese and is generally understood in Corsica due to its close relation with the Tuscan-influenced local language and Savoie. -

Standardization in Early English Orthography

Standardization in Early English Orthography Over thirty years ago Fred Brengelman pointed out that since at least 1909 and George Krapp’s Modern English: Its Growth and Present Use, it was widely assumed that English printers played the major role in the standardization of English spelling.1 Brengelman demonstrated convincingly that the role of the printers was at best minimal and that much more important was the work done in the late 16th and 17th centuries by early English orthoepists and spelling reformers – people like Richard Mulcaster, John Cheke, Thomas Smith, John Hart, William Bullokar, Alexander Gil, and Richard Hodges.2 Brengelman’s argument is completely convincing, but it concentrates on developments rather late in the history of English orthography – developments that were external to the system itself and basically top-down. It necessarily ignores the extent to which much standardization occurred naturally and internally during the 11th through 16th centuries. This early standardization was not a top-down process, but rather bottom-up, arising from the communication acts of individual spellers and their readers – many small actions by many agents. In what follows I argue that English orthography is an evolving system, and that this evolution produced a degree of standardization upon which the 16th and 17th century orthoepists could base their work, work that not only further rationalized and standardized our orthography, as Brengelman has shown, but also marked the beginning of the essentially top-down system that we have today. English Orthography as an Evolving Complex System. English orthography is not just an evolving system; it is an evolving complex system – adaptive, self-regulating, and self-organizing. -

ELL101: Intro to Linguistics Week 1 Phonetics &

ELL101: Intro to Linguistics Week 1 Phonetics & IPA Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Education and Language Acquisition Dept. LaGuardia Community College August 16, 2017 . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 1/41 Fields of linguistics • Week 1-2: Phonetics (physical sound properties) • Week 2-3: Phonology (speech sound rules) • Week 4: Morphology (word parts) • Week 5-6: Syntax (structure) • Week 7-8: Semantics (meaning) • Week 7-8: Pragmatics (conversation & convention) • Week 9: First & Second language acquisition • Week 10-12: Historical linguistics (history of language) • Week 10-12: Socio-linguistics (language in society) • Week 10-12: Neuro-linguistics (the brain and language) • Week 10-12: Computational linguistics (computer and language) • Week 10-12: Evolutional linguistics (how language evolved in human history) . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 2/41 Overview Phonetics Phonetics is a study of the characteristics of the speech sound (p.30; Yule (2010)) Branches of phonetics • Articulatory phonetics • how speech sounds are made • Acoustic phonetics • physical properties of speech sounds • Auditory phonetics • how speech sounds are perceived • See some examples of phonetics research: • Speech visualization (acoustic / auditory phonetics) • ”McGurk effect” (auditory phonetics) . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 3/41 Acoustic phonetics (example) • The speech wave (spectorogram) of ”[a] (as in above), [ɛ] (as in bed), and [ɪ] (as in bit)” 5000 ) z H ( y c n e u q e r F 0 0 . .0.3799. Time (s) . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 4/41 Acoustic phonetics (example) • The speech wave (spectorogram) of ”Was that a good movie you saw?” 5000 ) z H ( y c n e u q e r F 0 0 2.926 Time (s) . -

Teaching Initial Reading and Writing at the Very Beginning of Compulsory School Attendance in the Czech Primary School Phdr

FELA Initial Teaching in Europe 1st Symposium in Klagenfurt 2015 Teaching initial reading and writing at the very beginning of compulsory school attendance in the Czech Primary School PhDr. Marie Ernestová, Czech Republic 1 Introductory Facts • language typology: Czech is a flectional language • 7 cases in both singular and plural noun declination patterns and 6 forms in verbal conjugation (3 in the singular and 3 in the plural) • illogical grammar gender system (table=masculine, chair=feminine, window=neuter). 2 • language genealogy: Czech is a West Slavic language • with highly phonemic orthography it may be described as having regular spelling • the Czech alphabet consists of 42 letters (including the digraph ch, which is considered a single letter in Czech): • a á b c č d ď e é ě f g h ch i í j k l m n ň o ó p q r ř s š t ť u ú ů v w x y ý z ž 3 • the Czech orthographic system is diacritic. The háček /ˇ/ is added to standard Latin letters for expressing sounds which are foreign to the Latin language. The acute accent is used for long vowels. • There are two ways in Czech to write long [u:]: ú or ů. 4 • only one digraph: ´ch´ always pronounced the same, as /X/ as in the English loch. • All over Europe the ch-consonant combination makes problems as this ´/X/´ sound can be spelt in as many as eighteen ways: c, ć, ç,ċ,ĉ, č, ch, çh, ci, cs,cz,tch, tj,tš, tsch, tsi, tsj, tx and even k. -

Rank of Weighted Digraphs with Blocks

Rank of weighted digraphs with blocks∗ Ranveer Singh† Swarup Kumar Panda ‡ Naomi Shaked-Monderer§ Abraham Berman¶ October 10, 2018 Abstract Let G be a digraph and r(G) be its rank. Many interesting results on the rank of an undirected graph appear in the literature, but not much information about the rank of a digraph is available. In this article, we study the rank of a digraph using the ranks of its blocks. In particular, we define classes of digraphs, namely r2-digraph, and r0-digraph, for which the rank can be exactly determined in terms of the ranks of subdigraphs of the blocks. Furthermore, the rank of directed trees, simple biblock graphs, and some simple block graphs are studied. Keywords: r2-digraphs, r0-digraphs, tree digraphs, block graphs, biblock graphs AMS Subject Classifications. 15A15, 15A18, 05C50 1 Introduction A well-known problem, proposed in 1957 by Collatz and Sinogowitz, is to characterize graphs with positive nullity [19]. Nullity of graphs is applicable in various branches of science, in particular, quantum chemistry, H¨uckel molecular orbital theory [10], [13] and social network theory [14]. For more detail on the applications see [10]. Many significant results on the nullity of undirected graphs are available in the literature, see [4, 7, 11, 12, 15, 12, 2, 3, 20]. Recently in [9, 8, 6] nullity of undirected graphs was studied using cut-vertices and connected components. The results are used to calculate the nullity of line graphs of undirected graphs. Apart from the connected components, it turns out that the blocks are also interesting subgraphs of a graph, which can be utilized to know its determinant [17, 16]. -

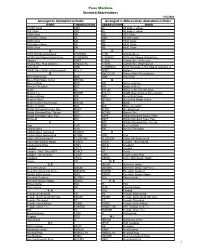

Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order Arranged in Alphabetical Order Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations

Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations 1/25/2008 Arranged in Alphabetical Order Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order WORD ABBREVIATION ABBREVIATION WORD 10,000 Class 10M 45 45 degree elbow 150 Class 150 90 90 degree elbow 3000 Class 3M 150 150 Class 45 degree elbow 45 10M 10,000 Class 6000 Class 6M 3M 3000 Class 90 degree elbow 90 6M 6000 Class 9000 Class 9M 9M 9000 Class A A A105 Hot Dip Galvanized A105HDG A105 Carbon Steel A105N Hot Dipped Galvanized A105NHDG A105HDG A105 Hot Dipped Galvanized Adapter ADPT A105A Carbon Steel Annealed Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove AMOCO PL A105N Carbon Steel Normalized Annealed ANN A105NHDG A105 Normalized Hot Dipped Galvanized ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* B16.11 ADPT Adapter B AMOCO PL Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove Bevel Both Ends BBE ANN Annealed Bevel End Nipple Outlet BE NOL B Bevel x Plain BXP B/B Brass to Brass Bevel x Threaded BXT B/S Brass to Steel Blank BL B/S UN Brass to Steel Seat Union Branch Tee BRTEE B16.11 ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* Brass to Brass B/B BBE Bevel Both Ends Brass to Steel B/S BE NOL Bevel End Nipple Outlet Brass to Steel Seat Union B/S UN BL Blank Braze-on Outlet BOL BOL Braze-on Outlet British Standard Parallel Pipe BSPP BOSS Welding Boss British Standard Pipe Thread BST BRTEE Branch Tee British Standard Taper Pipe BSPT BSPP British Standard Parallel Pipe Buttweld BW BSPT British Standard Taper Pipe C BST British Standard Pipe Thread Cap CAP BXP Bevel x Plain Carbon Steel A105 BXT Bevel x Threaded Carbon Steel Annealed A105HT C Carbon Steel Normalized A105N CAP Cap Class 200 -

31 Vowel Digraph Oo

Sort Vowel Digraph oo 31 Objectives • To identify spelling patterns of vowel digraph oo Words • To read, sort, and write words with vowel digraph oo o˘o oˉo = uˉ Oddball brook nook fool spool could Materials for Within Word Pattern crook soot groom spoon should Big Book of Rhymes, “The Puppet Show,” page 55 foot stood hoop stool would hood wood noon tool Whiteboard Activities DVD-ROM, Sort 31 hook wool root troop Teacher Resource CD-ROM, Sort 31 and Follow the Dragon Game Student Book, pages 121–124 Words Their Way Library, The House That Stood on Booker Hill Introduce/Model Small Groups • Read a Rhyme Read “The Puppet Show,” and Extend the Sort emphasize words with the vowel digraph oo. (wood, book, took; soon, noon) Ask students to locate these Alternative Sort: Brainstorming words, and help them write the words in two columns, Ask students to think of other words that contain according to vowel sound. Help students hear the oo. Write their responses on index cards. When different pronunciations of the vowel digraph oo. students have completed brainstorming, ask them to identify and sort all the words they named • Model Use the whiteboard DVD or the CD word according to the vowel sound of oo. cards. Define in context any that may be unfamiliar to students. Demonstrate how to sort the words ELL English Language Learners according to the sound of the digraph oo. Point out Explain that a nook is “a hidden place,” and that that would, could, and should do not contain the groom can have several meanings, including “a digraph oo, so they belong in the oddball category. -

Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W

Knowl. Org. 46(2019)No.3 209 W. Korwin and H. Lund. Alphabetization Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W. Dunedin Rd., Columbus, OH 43214, USA, <[email protected]> **University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies, DK-2300 Copenhagen S Denmark, <[email protected]> Wendy Korwin received her PhD in American studies from the College of William and Mary in 2017 with a dissertation entitled Material Literacy: Alphabets, Bodies, and Consumer Culture. She has worked as both a librarian and an archivist, and is currently based in Columbus, Ohio, United States. Haakon Lund is Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies in Denmark. He is educated as a librarian (MLSc) from the Royal School of Library and Information Science, and his research includes research data management, system usability and users, and gaze interaction. He has pre- sented his research at international conferences and published several journal articles. Korwin, Wendy and Haakon Lund. 2019. “Alphabetization.” Knowledge Organization 46(3): 209-222. 62 references. DOI:10.5771/0943-7444-2019-3-209. Abstract: The article provides definitions of alphabetization and related concepts and traces its historical devel- opment and challenges, covering analog as well as digital media. It introduces basic principles as well as standards, norms, and guidelines. The function of alphabetization is considered and related to alternatives such as system- atic arrangement or classification. Received: 18 February 2019; Revised: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 21 March 2019 Keywords: order, orders, lettering, alphabetization, arrangement † Derived from the article of similar title in the ISKO Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization Version 1.0; published 2019-01-10. -

Conversion Table a = 1 B = 2 C = 3 D = 4 E = 5 F = 6 G = 7 H = 8 I = 9 J = 10 K =11 L = 12 M = 13 N =14 O =15 P = 16 Q =17 R

Classroom Activity 2 Math 113 The Dating Game Introduction: Disclaimer: Although this is called the “Dating Game”, it is merely intended to help the student gain understanding of the concept of Standard Deviation. It is not intended to help students find dates. The day after Thanksgiving, 1996, I was driving my sister, Conversion Table brother-in-law, and sister-in-law over to meet my brother in A=1 K=11 U=21 Springfield at the Mission where he and his wife helped out. B=2 L=12 V=22 During this drive, I ask my sister, “How do you know which C=3 M=13 W=23 woman is the right one for you?”. Now, my sister was born D=4 N=14 X=24 a Jones, and like the rest of the family, she can make E=5 O=15 Y=25 anything sound believable. Without missing a beat, she F=6 P=16 Z=26 said, “You take the letters in her name, convert them to G=7 Q=17 numbers, find the standard deviation, and whoever’s H=8 R=18 standard deviation is closest to yours is the woman for you.” I=9S=19 I was so proud of my sister, that was a really good answer. J=10 T=20 Then, she followed it up with “Actually, if you can find a woman who knows what a standard deviation is, that’s the woman for you.” The first part was easy, take each letter in your name and convert it to a number. Use the system where an A=1, B=2, .. -

Master's Project at ICT, KTH Examensarbete Vid ICT, KTH

Master's Project at ICT, KTH Examensarbete vid ICT, KTH Automated source-to-source translation from Java to C++ Automatisk källkodsöversättning från Java till C++ JACEK SIEKA [email protected] Master's Thesis in Software Engineering Examensarbete inom programvaruteknik Supervisor and examiner: Thomas Sjöland Handledare och examinator: Thomas Sjöland Abstract Reuse of Java libraries and interoperability with platform native components has traditionally been limited to the application programming interface offered by the reference implementation of Java, the Java Native Interface. In this thesis the feasibility of another approach, automated source-to-source translation from Java to C++, is examined starting with a survey of the current research. Using the Java Language Specification as guide, translations for the constructs of the Java language are proposed, focusing on and taking advantage of the syntactic and semantic similarities between the two languages. Based on these translations, a tool for automatically translating Java source code to C++ has been developed and is presented in the text. Experimentation shows that a simple application and the core Java libraries it depends on can automatically be translated, producing equal output when built and run. The resulting source code is readable and maintainable, and therefore suitable as a starting point for further development in C++. With the fully automated process described, source-to-source translation becomes a viable alternative when facing a need for functionality already implemented in a Java library or application, saving considerable resources that would otherwise have to be spent rewriting the code manually. Sammanfattning Återanvändning av Java-bibliotek och interoperabilitet med plattformspecifika komponenter har traditionellt varit begränsat till det programmeringsgränssnitt som erbjuds av referensimplementationen av Java, Java Native Interface.