Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor's Thesis Studies on Multilingual Information Processing

NAIST-IS-DT9761021 Doctor’s Thesis Studies on Multilingual Information Processing on the Internet Akira Maeda September 18, 2000 Department of Information Systems Graduate School of Information Science Nara Institute of Science and Technology Doctor’s Thesis submitted to Graduate School of Information Science, Nara Institute of Science and Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR of ENGINEERING Akira Maeda Thesis committee: Shunsuke Uemura, Professor Yuji Matsumoto, Professor Minoru Ito, Professor Masatoshi Yoshikawa, Associate Professor Studies on Multilingual Information Processing on the Internet ∗ Akira Maeda Abstract With the increasing popularity of the Internet in various part of the world, the languages used for Web documents are expanded from English to various languages. However, there are many unsolved problems in order to realize an information system which can handle such multilingual documents in a unified manner. From the user’s point of view, three most fundamental text processing functions for the general use of the World Wide Web are display, input, and retrieval of the text. However, for languages such as Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, character fonts and input methods that are necessary for displaying and inputting texts, are not always installed on the client side. From the system’s point of view, one of the most troublesome problems is that, many Web documents do not have meta information of the character coding system and the language used for the document itself, although character coding systems used for Web documents vary according to the language. It may result in troubles such as incorrect display on Web browsers, and inaccurate indexing on Web search engines. -

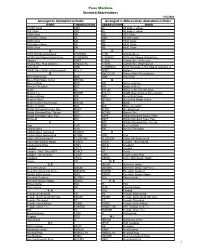

Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order Arranged in Alphabetical Order Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations

Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations 1/25/2008 Arranged in Alphabetical Order Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order WORD ABBREVIATION ABBREVIATION WORD 10,000 Class 10M 45 45 degree elbow 150 Class 150 90 90 degree elbow 3000 Class 3M 150 150 Class 45 degree elbow 45 10M 10,000 Class 6000 Class 6M 3M 3000 Class 90 degree elbow 90 6M 6000 Class 9000 Class 9M 9M 9000 Class A A A105 Hot Dip Galvanized A105HDG A105 Carbon Steel A105N Hot Dipped Galvanized A105NHDG A105HDG A105 Hot Dipped Galvanized Adapter ADPT A105A Carbon Steel Annealed Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove AMOCO PL A105N Carbon Steel Normalized Annealed ANN A105NHDG A105 Normalized Hot Dipped Galvanized ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* B16.11 ADPT Adapter B AMOCO PL Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove Bevel Both Ends BBE ANN Annealed Bevel End Nipple Outlet BE NOL B Bevel x Plain BXP B/B Brass to Brass Bevel x Threaded BXT B/S Brass to Steel Blank BL B/S UN Brass to Steel Seat Union Branch Tee BRTEE B16.11 ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* Brass to Brass B/B BBE Bevel Both Ends Brass to Steel B/S BE NOL Bevel End Nipple Outlet Brass to Steel Seat Union B/S UN BL Blank Braze-on Outlet BOL BOL Braze-on Outlet British Standard Parallel Pipe BSPP BOSS Welding Boss British Standard Pipe Thread BST BRTEE Branch Tee British Standard Taper Pipe BSPT BSPP British Standard Parallel Pipe Buttweld BW BSPT British Standard Taper Pipe C BST British Standard Pipe Thread Cap CAP BXP Bevel x Plain Carbon Steel A105 BXT Bevel x Threaded Carbon Steel Annealed A105HT C Carbon Steel Normalized A105N CAP Cap Class 200 -

Proposal to Encode 0D5F MALAYALAM LETTER ARCHAIC II

Proposal to encode 0D5F MALAYALAM LETTER ARCHAIC II Shriramana Sharma, jamadagni-at-gmail-dot-com, India 2012-May-22 §1. Introduction In the Malayalam Unicode encoding, the independent letter form for the long vowel Ī is: ഈ where the length mark ◌ൗ is appended to the short vowel ഇ to parallel the symbols for U/UU i.e. ഉ/ഊ. However, Ī was originally written as: As these are entirely different representations of Ī, although their sound value may be the same, it is proposed to encode the archaic form as a separate character. §2. Background As the core Unicode encoding for the major Indic scripts is based on ISCII, and the ISCII code chart for Malayalam only contained the modern form for the independent Ī [1, p 24]: … thus it is this written form that came to be encoded as 0D08 MALAYALAM LETTER II. While this “new” written form is seen in print as early as 1936 CE [2]: … there is no doubt that the much earlier form was parallel to the modern Grantha , both of which are derived from the old Grantha Ī as seen below: 1 ma - īdṛgvidhā | tatarāya īṇ Old Grantha from the Iḷaiyānputtūr copper plates [3, p 13]. Also seen is the Vatteḻuttu Ī of the same time (line 2, 2nd char from right) which also exhibits the two dots. Of course, both are derived from old South Indian Brahmi Ī which again has the two dots. It is said [entire paragraph: Radhakrishna Warrier, personal communication] that it was the poet Vaḷḷattōḷ Nārāyaṇa Mēnōn (1878–1958) who introduced the new form of Ī ഈ. -

Conversion Table a = 1 B = 2 C = 3 D = 4 E = 5 F = 6 G = 7 H = 8 I = 9 J = 10 K =11 L = 12 M = 13 N =14 O =15 P = 16 Q =17 R

Classroom Activity 2 Math 113 The Dating Game Introduction: Disclaimer: Although this is called the “Dating Game”, it is merely intended to help the student gain understanding of the concept of Standard Deviation. It is not intended to help students find dates. The day after Thanksgiving, 1996, I was driving my sister, Conversion Table brother-in-law, and sister-in-law over to meet my brother in A=1 K=11 U=21 Springfield at the Mission where he and his wife helped out. B=2 L=12 V=22 During this drive, I ask my sister, “How do you know which C=3 M=13 W=23 woman is the right one for you?”. Now, my sister was born D=4 N=14 X=24 a Jones, and like the rest of the family, she can make E=5 O=15 Y=25 anything sound believable. Without missing a beat, she F=6 P=16 Z=26 said, “You take the letters in her name, convert them to G=7 Q=17 numbers, find the standard deviation, and whoever’s H=8 R=18 standard deviation is closest to yours is the woman for you.” I=9S=19 I was so proud of my sister, that was a really good answer. J=10 T=20 Then, she followed it up with “Actually, if you can find a woman who knows what a standard deviation is, that’s the woman for you.” The first part was easy, take each letter in your name and convert it to a number. Use the system where an A=1, B=2, .. -

11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Review Words Challenge Words

Spelling: Digraphs Name Fold back the paper 1. 1. thirty along the dotted line. 2. 2. width Use the blanks to write each word as it is read 3. 3. northern aloud. When you fi nish 4. 4. fi fth the test, unfold the paper. Use the list at 5. 5. choose the right to correct any 6. 6. touch spelling mistakes. 7. 7. chef 8. 8. chance 9. 9. pitcher 10. 10. kitchen 11. 11. sketched 12. 12. ketchup 13. 13. snatch 14. 14. stretching 15. 15. rush 16. 16. whine 17. 17. whirl 18. 18. bring 19. 19. graph 20. 20. photo Review Words 21. 21. unload Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 22. 22. relearn 23. 23. subway Challenge Words 24. 24. expression 25. 25. theater Phonics/Spelling • Grade 4 • Unit 2 • Week 2 37 Spelling: Digraphs Name thirty choose pitcher snatch whirl width touch kitchen stretching bring northern chef sketched rush graph fi fth chance ketchup whine photo A. Underline the spelling word in each row that rhymes with the word in bold type. Write the spelling word on the line. 1. much match touch luck 2. sting bring brag stint 3. fetching resting guessing stretching 4. pants stand lamp chance 5. dirty thirty forty wiry 6. shine mind whine lane 7. news loose stew choose 8. catch clutch snatch snake 9. laugh graph rough roof 10. fl ush crash rush puts Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 11. clef chef step leaf 12. etched skipped punched sketched 13. hurl hurt whirl while 14. richer pitcher sister listener B. -

Digraphs Th, Sh, Ch, Ph

At the Beach Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph • Generalization Words can have two consonants together that are pronounced as one sound: southern, shovel, chapter, hyRJlen. Word Sort Sort the list words by digraphs th, sh, ch, and ph. th ch 1. shovel 2. southern 1. 11. 3. northern 4. chapter 2. 12. 5. hyphen 6. chosen 7. establish 3. 13. 8. although 9. challenge 10. approach 4. 14. 11. astonish 12. python 5. 15. 13. shatter 0 14. ethnic 15. shiver sh 16. Ul 16. pharmacy .,; 6. ..~ ~ 17. charity a: !l 17. .c 18. china CJ) a: 19. attach 7. ~.. 20. ostrich i 18. ~.. 8. "'5 .; £ c ph 0 ~ C) 9. 19. ;ii" c: <G~ ,f 0 E 10. 20. CJ) ·c i;: 0 0 ~ + Home Home Activity Your child is learning about four sounds made with two consonants together, called ~ digraphs. Ask your child to tell you what those four sounds are and give one list word for each sound. DVD•62 Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph Name Unit 2Weel1 1Interactive Review Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph shovel hyphen challenge shatter charity southern chosen approach ethnic china northern establish astonish shiver attach chapter although python pharmacy ostrich Alphabetize Write the ten list words below in alphabetical order. ethnic python ostrich charity hyphen although chapter establish northern southern 1. 6. 2. 7. c, 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. Synonyms Write the list word that has the same or nearly the same meaning. 11. surprise 16. drugstore 12. dare 17. break 13. shake 18. fasten "'u £ c 14. 19. dig 0 pottery ·;; " 15. -

MUFI Character Recommendation V. 3.0: Alphabetical Order

MUFI character recommendation Characters in the official Unicode Standard and in the Private Use Area for Medieval texts written in the Latin alphabet ⁋ ※ ð ƿ ᵹ ᴆ ※ ¶ ※ Part 1: Alphabetical order ※ Version 3.0 (5 July 2009) ※ Compliant with the Unicode Standard version 5.1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ※ Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI) ※ www.mufi.info ISBN 978-82-8088-402-2 ※ Characters on shaded background belong to the Private Use Area. Please read the introduction p. 11 carefully before using any of these characters. MUFI character recommendation ※ Part 1: alphabetical order version 3.0 p. 2 / 165 Editor Odd Einar Haugen, University of Bergen, Norway. Background Version 1.0 of the MUFI recommendation was published electronically and in hard copy on 8 December 2003. It was the result of an almost two-year-long electronic discussion within the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (http://www.mufi.info), which was established in July 2001 at the International Medi- eval Congress in Leeds. Version 1.0 contained a total of 828 characters, of which 473 characters were selected from various charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 355 were located in the Private Use Area. Version 1.0 of the recommendation is compliant with the Unicode Standard version 4.0. Version 2.0 is a major update, published electronically on 22 December 2006. It contains a few corrections of misprints in version 1.0 and 516 additional char- acters (of which 123 are from charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 393 are additions to the Private Use Area). -

Iso/Iec Jtc 1/Sc 2/Wg 2 N ___Iso/Iec Jtc 1/Sc 2/Wg 2/Irg N 1180

SC2/WG2 N3063 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N _____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2/IRG N 1180 ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2/IRG Ideographic Rapporteur Group (IRG) TITLE: Proposed additions to the CJK Strokes block of the UCS SOURCE: IRG Rapporteur STATUS: Submission from the IRG to WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 DATE: 2006-4-3 REFERENCE: WG2 N2807R, N2808R, IRG N1174 ATTACHMENTS: IRG N1181 (“Summary for Stroke submission”) Summary This document proposes the addition of twenty new CJK Strokes to the CJK Strokes block of the UCS. WG2 resolution M45.34 (N2754R) expanded the scope of IRG work to include CJK Strokes. The CJK Strokes block (U+31CO..U+31EF) now contains a total of sixteen CJK Strokes (U+31C0..U+31CF), derived from HKSCS (ISO/IEC 10646:2003/Amd.1). The IRG formed ad-hoc groups to complete the repertoire of common CJK Strokes, and finalized the repertoire in the IRG#25 meeting held in Berkeley, California, U.S.A. The twenty new CJK Strokes are proposed for code points in the range (U+31D0..U+31E3). Information on naming conventions and collation is also provided. List of the proposed characters, character names and code positions 31C 31D 31E 31C0 CJK STROKE T 31E0 CJK STROKE HXWG 0 ㇀ ㇐ ㇠ 31C1 CJK STROKE WG 31E1 CJK STROKE HZZZG 31C2 CJK STROKE XG 31E2 CJK STROKE PG 1 ㇁ ㇑ ㇡ 31C3 CJK STROKE BXG 31E3 CJK STROKE Q 31C4 CJK STROKE SW 2 ㇂ ㇒ ㇢ 31C5 CJK STROKE HZZ 31C6 CJK STROKE HZG 31C7 CJK STROKE HP 3 ㇃ ㇓ ㇣ 31C8 CJK STROKE HZWG 31C9 CJK STROKE SZWG 4 ㇄ ㇔ 31CA CJK STROKE HZT 31CB CJK STROKE HZZP 5 ㇅ ㇕ 31CC CJK STROKE HPWG 31CD CJK STROKE -

Surface Or Essence: Beyond the Coded Character Set Model

Surface or Essence: Beyond the Coded Character Set Model. Shigeki Moro1) Abstract For almost all users, the coded character set model is the only way to use characters with their computers. Although there have been frequent arguments about the many problems of coded character sets, until now, there was almost nothing on the philosophical consideration on a character in the field of Computer science. In this paper, the similarity between the coded character set model and Aristotle’s Essentialism and the consequent problems derived from it, is discussed. Then the importance of the surface of the character is pointed out using the ´ecrituretheory of Jacques Derrida. Lastly, the Chaon model of the CHISE project is introduced as one of the solutions to this problem. Keywords: Unicode, Aristotle’s Essentialism, Derrida’s Theory of ´ecriture,Chaon model “Depth must be hidden. Where? On the surface.” other local and super character code sets are still —Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929) being developed, and the repertoires of the existing character sets are increasing even now. What users 1 Introduction. can only do is to choose and follow these character sets. Writing, is not only considered as one of the most The main reason for this is that there are both fundamental mediums of intellectual activities, but sides: Writing is not only dependent on a context, also a frequently used one, which is not restricted but that it is transmitted exceeding the context (it to the use of computers alone. Needless to say that is contrastive with oral language being indivisible the coded character set model (abbreviation being from a context). -

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Edited by Susan Baddeley Anja Voeste De Gruyter Mouton An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 ThisISBN work 978-3-11-021808-4 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, ase-ISBN of February (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 LibraryISSN 0179-0986 of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ae-ISSN CIP catalog 0179-3256 record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-028812-4 e-ISBNBibliografische 978-3-11-028817-9 Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- fie;This detaillierte work is licensed bibliografische under the DatenCreative sind Commons im Internet Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs über 3.0 License, Libraryhttp://dnb.dnb.deas of February of Congress 23, 2017.abrufbar. -

Electronic Document Preparation Pocket Primer

Electronic Document Preparation Pocket Primer Vít Novotný December 4, 2018 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (cc by 3.0) Contents Introduction 1 1 Writing 3 1.1 Text Processing 4 1.1.1 Character Encoding 4 1.1.2 Text Input 12 1.1.3 Text Editors 13 1.1.4 Interactive Document Preparation Systems 13 1.1.5 Regular Expressions 14 1.2 Version Control 17 2 Markup 21 2.1 Meta Markup Languages 22 2.1.1 The General Markup Language 22 2.1.2 The Extensible Markup Language 23 2.2 Markup on the World Wide Web 28 2.2.1 The Hypertext Markup Language 28 2.2.2 The Extensible Hypertext Markup Language 29 2.2.3 The Semantic Web and Linked Data 31 2.3 Document Preparation Systems 32 2.3.1 Batch-oriented Systems 35 2.3.2 Interactive Systems 36 2.4 Lightweight Markup Languages 39 3 Design 41 3.1 Fonts 41 3.2 Structural Elements 42 3.2.1 Paragraphs and Stanzas 42 iv CONTENTS 3.2.2 Headings 45 3.2.3 Tables and Lists 46 3.2.4 Notes 46 3.2.5 Quotations 47 3.3 Page Layout 48 3.4 Color 48 3.4.1 Theory 48 3.4.2 Schemes 51 Bibliography 53 Acronyms 61 Index 65 Introduction With the advent of the digital age, typesetting has become available to virtually anyone equipped with a personal computer. Beautiful text documents can now be crafted using free and consumer-grade software, which often obviates the need for the involvement of a professional designer and typesetter. -

The Book Unbound: Two Centuries of Indian Print 14Th-15Th July 2017 H.L

The Book Unbound: Two Centuries of Indian Print 14th-15th July 2017 H.L. Roy Auditorium, Jadavpur University Abstracts Keynote Address A Note on the Use of Punctuation in Early Printed Books in Bengali Swapan Chakravorty Punctuation was sparse and uneven in Bengali handwritten books. Poetry, it is well known, used the vertical virgule to end the first line of an end-stopped couplet (payaar), and two vertical lines at the end of the second. For triplets or tripadis, each set of three used a space between the first and the second, and the first set was closed by a vertical line and the second by a pair of virgulae. These marks were not necessarily grammatical or rhetorical, but more often than not prosodic. Line divisions, however, were erratic and optional, even after the introduction of print. Punctuated prose appeared only with the coming of print, instances of earlier manuscript prose being rare except in letters and a few documents relating to property, court orders and land records. Rammohan Roy's (1772-1833) early Bengali prose hardly employed punctuation. Between 1819 and 1833, when he was trying to fashion a modern prose and to codify its grammar, we see his texts using a sprinkling of commas, question marks and semi- colons. Common wisdom persuades us that it was Iswarchandra Vidyasagar (1820-91), scholar, author, social activist and printer, who standardized punctuation in Bengali printed prose. The disposition of Western punctuation, paragraphs and line-divisions could at times be excessive in Vidyasagar, impeding the rhetorical flow of a passage and distorting the 'eye-voice span'.