Foundation A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chieftains Into Ancestors: Imperial Expansion and Indigenous Society in Southwest China

1 Chieftains into Ancestors: Imperial Expansion and Indigenous Society in Southwest China. David Faure and Ho Ts’ui-p’ing, editors. Vancouver and Toronto: University of British Columbia Press, 2013. ISBN: 9780774823692 The scholars whose essays appear in this volume all attempt, in one way or another, to provide a history of southern and southwestern China from the perspective of the people who lived and still live there. One of the driving forces behind the impressive span of research across several cultural and geographical areas is to produce or recover the history(ies) of indigenous conquered people as they saw and experienced it, rather than from the perspective of the Chinese imperial state. It is a bold and fresh look at a part of China that has had a long-contested relationship with the imperial center. The essays in this volume are all based on extensive fieldwork in places ranging from western Yunnan to western Hunan to Hainan Island. Adding to the level of interest in these pieces is the fact that these scholars also engage with imperial-era written texts, as they interrogate the different narratives found in oral (described as “ephemeral”) rituals and texts written in Chinese. In fact, it is precisely the nexus or difference between these two modes of communicating the past and the relationship between the local and the central state that energizes all of the scholarship presented in this collection of essays. They bring a very different understanding of how the Chinese state expanded its reach over this wide swath of territory, sometimes with the cooperation of indigenous groups, sometimes in stark opposition, and how indigenous local traditions were, and continue to be, reified and constructed in ways that make sense of the process of state building from local perspectives. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

SSA1208 / GES1005 – Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past and Present

SSA1208 / GES1005 – Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past and Present Group Essay Ho Lim Keng Temple Prepared By: Tutorial [D5] Chew Si Hui (A0130382R) Kwek Yee Ying (A0130679Y) Lye Pei Xuan (A0146673X) Soh Rolynn (A0130650W) Submission Date: 31th March 2017 1 Content Page 1. Introduction to Ho Lim Keng Temple 3 2. Exterior & Courtyard 3 3. Second Level 3 4. Interior & Main Hall 4 5. Main Gods 4 6. Secondary Gods 5 7. Our Views 6 8. Experiences Encountered during our Temple Visit 7 9. References 8 10. Appendix 8 2 1. Introduction to Ho Lim Keng Temple Ho Lim Keng Temple is a Taoist temple and is managed by common surname association, Xu (许) Clan. Chinese clan associations are benevolent organizations of popular origin found among overseas Chinese communities for individuals with the same surname. This social practice arose several centuries ago in China. As its old location was acquisited by the government for redevelopment plans, they had moved to a new location on Outram Hill. Under the leadership of 许木泰宗长 and other leaders, along with the clan's enthusiastic response, the clan managed to raise a total of more than $124,000, and attained their fundraising goal for the reconstruction of the temple. Reconstruction works commenced in 1973 and was completed in 1975. Ho Lim Keng Temple was advocated by the Xu Clan in 1961, with a board of directors to manage internal affairs. In 1966, Ho Lim Keng Temple applied to the Registrar of Societies and was approved on February 28, 1967 and then was published in the Government Gazette on March 3. -

Opening Remarks Guo Changgang: Good Morning

Opening Remarks Guo Changgang: Good morning. Let’s start our workshop. First, I want to say many, many thanks to our dear guests and colleagues who took their time to participate in this event. And I should also firstly thank Professor Mark Juergensmeyer. Actually, he had this idea when we met last year in Chicago, where we talked about it. In recent years, my field and my interest is in religion and its’ globalizing force, the role of religion and its’ globalizing force in some specific religious countries; the role of religion and also the tension between religion and nation-states. So when we talked together, we came to this idea to make this joint event. So I should thank Mark Juergensmeyer actually for making this event possible. And also thanks to Dinah. Dinah, you actually give a big support to Mark Juergensmeyer’s project. Guo Changgang: Now I’d like to introduce our colleagues and every participant. Professor Tajima Tadaatsu. Oh, Tadaatsu Tajima. Can we just call you Tad? He is a professor from Tenshi College, Japan. Dr. Greg Auberry from Catholic Relief Services, Center in Cambodia. Professor Zhang Zhigang, he is still on the way he is a Professor from Peking University. He’s still on the way up here. Professor David A. Palmer from Hong Kong University. I think your field is Taoism. Chinese religion and Taoism, and director She Hongye from the Amity Foundation. Dr. Victor from UCSB center of Santa Barbara and colleague to Mark. Mark Juergensmeyer : More than a colleague. He is my right hand man. -

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China Noga Ganany Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Noga Ganany All rights reserved ABSTRACT Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late Ming China Noga Ganany In this dissertation, I examine a genre of commercially-published, illustrated hagiographical books. Recounting the life stories of some of China’s most beloved cultural icons, from Confucius to Guanyin, I term these hagiographical books “origin narratives” (chushen zhuan 出身傳). Weaving a plethora of legends and ritual traditions into the new “vernacular” xiaoshuo format, origin narratives offered comprehensive portrayals of gods, sages, and immortals in narrative form, and were marketed to a general, lay readership. Their narratives were often accompanied by additional materials (or “paratexts”), such as worship manuals, advertisements for temples, and messages from the gods themselves, that reveal the intimate connection of these books to contemporaneous cultic reverence of their protagonists. The content and composition of origin narratives reflect the extensive range of possibilities of late-Ming xiaoshuo narrative writing, challenging our understanding of reading. I argue that origin narratives functioned as entertaining and informative encyclopedic sourcebooks that consolidated all knowledge about their protagonists, from their hagiographies to their ritual traditions. Origin narratives also alert us to the hagiographical substrate in late-imperial literature and religious practice, wherein widely-revered figures played multiple roles in the culture. The reverence of these cultural icons was constructed through the relationship between what I call the Three Ps: their personas (and life stories), the practices surrounding their lore, and the places associated with them (or “sacred geographies”). -

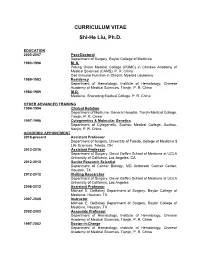

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D. EDUCATION 2003-2007 Post-Doctoral Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine 1993-1996 M. S. Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS). P. R. China Cell Immune Function in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia 1989-1993 Residency Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1984-1989 M.D. Medicine, Shandong Medical College, P. R. China OTHER ADVANCED TRAINING 1994-1994 Clinical Rotation Department of Medicine, General Hospital, Tianjin Medical College, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-1998 Cytogenetics & Molecular Genetics Department of Cytogenetic, Suzhou Medical College, Suzhou, Nanjin, P. R. China ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT 2016-present Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, University of Toledo, College of Medicine $ Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 2013-2016 Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles, CA 2012-2013 Senior Research Scientist Department of Cancer Biology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 2012-2012 Visiting Researcher Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles 2008-2012 Assistant Professor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2007-2008 Instructor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2002-2003 Associate Professor Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-2002 Doctor-in-Charge Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China HONORS OR AWARDS 2015 Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research award. -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Xi Jinping's Inner Circle (Part 2: Friends from Xi's Formative Years)

Xi Jinping’s Inner Circle (Part 2: Friends from Xi’s Formative Years) Cheng Li The dominance of Jiang Zemin’s political allies in the current Politburo Standing Committee has enabled Xi Jinping, who is a protégé of Jiang, to pursue an ambitious reform agenda during his first term. The effectiveness of Xi’s policies and the political legacy of his leadership, however, will depend significantly on the political positioning of Xi’s own protégés, both now and during his second term. The second article in this series examines Xi’s longtime friends—the political confidants Xi met during his formative years, and to whom he has remained close over the past several decades. For Xi, these friends are more trustworthy than political allies whose bonds with Xi were built primarily on shared factional association. Some of these confidants will likely play crucial roles in helping Xi handle the daunting challenges of the future (and may already be helping him now). An analysis of Xi’s most trusted associates will not only identify some of the rising stars in the next round of leadership turnover in China, but will also help characterize the political orientation and worldview of the influential figures in Xi’s most trusted inner circle. “Who are our enemies? Who are our friends?” In the early years of the Chinese Communist movement, Mao Zedong considered this “a question of first importance for the revolution.” 1 This question may be even more consequential today, for Xi Jinping, China’s new top leader, than at any other time in the past three decades. -

A Comparison of the Korean and Japanese Approaches to Foreign Family Names

15 A Comparison of the Korean and Japanese Approaches to Foreign Family Names JIN Guanglin* Abstract There are many foreign family names in Korean and Japanese genealogies. This paper is especially focused on the fact that out of approximately 280 Korean family names, roughly half are of foreign origin, and that out of those foreign family names, the majority trace their beginnings to China. In Japan, the Newly Edited Register of Family Names (新撰姓氏錄), published in 815, records that out of 1,182 aristocratic clans in the capital and its surroundings, 326 clans—approximately one-third—originated from China and Korea. Does the prevalence of foreign family names reflect migration from China to Korea, and from China and Korea to Japan? Or is it perhaps a result of Korean Sinophilia (慕華思想) and Japanese admiration for Korean and Chinese cultures? Or could there be an entirely distinct explanation? First I discuss premodern Korean and ancient Japanese foreign family names, and then I examine the formation and characteristics of these family names. Next I analyze how migration from China to Korea, as well as from China and Korea to Japan, occurred in their historical contexts. Through these studies, I derive answers to the above-mentioned questions. Key words: family names (surnames), Chinese-style family names, cultural diffusion and adoption, migration, Sinophilia in traditional Korea and Japan 1 Foreign Family Names in Premodern Korea The precise number of Korean family names varies by record. The Geography Annals of King Sejong (世宗實錄地理志, 1454), the first systematic register of Korean family names, records 265 family names, but the Survey of the Geography of Korea (東國輿地勝覽, 1486) records 277. -

A Study of Xu Xu's Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS

Allegories and Appropriations of the ―Ghost‖: A Study of Xu Xu‘s Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Qin Chen Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Master's Examination Committee: Kirk Denton, Advisor Patricia Sieber Copyright by Qin Chen 2010 Abstract This thesis is a comparative study of Xu Xu‘s (1908-1980) novella Ghost Love (1937) and three film adaptations made in 1941, 1956 and 1995. As one of the most popular writers during the Republican period, Xu Xu is famous for fiction characterized by a cosmopolitan atmosphere, exoticism, and recounting fantastic encounters. Ghost Love, his first well-known work, presents the traditional narrative of ―a man encountering a female ghost,‖ but also embodies serious psychological, philosophical, and even political meanings. The approach applied to this thesis is semiotic and focuses on how each text reflects the particular reality and ethos of its time. In other words, in analyzing how Xu‘s original text and the three film adaptations present the same ―ghost story,‖ as well as different allegories hidden behind their appropriations of the image of the ―ghost,‖ the thesis seeks to broaden our understanding of the history, society, and culture of some eventful periods in twentieth-century China—prewar Shanghai (Chapter 1), wartime Shanghai (Chapter 2), post-war Hong Kong (Chapter 3) and post-Mao mainland (Chapter 4). ii Dedication To my parents and my husband, Zhang Boying iii Acknowledgments This thesis owes a good deal to the DEALL teachers and mentors who have taught and helped me during the past two years at The Ohio State University, particularly my advisor, Dr. -

Surname Methodology in Defining Ethnic Populations : Chinese

Surname Methodology in Defining Ethnic Populations: Chinese Canadians Ethnic Surveillance Series #1 August, 2005 Surveillance Methodology, Health Surveillance, Public Health Division, Alberta Health and Wellness For more information contact: Health Surveillance Alberta Health and Wellness 24th Floor, TELUS Plaza North Tower P.O. Box 1360 10025 Jasper Avenue, STN Main Edmonton, Alberta T5J 2N3 Phone: (780) 427-4518 Fax: (780) 427-1470 Website: www.health.gov.ab.ca ISBN (on-line PDF version): 0-7785-3471-5 Acknowledgements This report was written by Dr. Hude Quan, University of Calgary Dr. Donald Schopflocher, Alberta Health and Wellness Dr. Fu-Lin Wang, Alberta Health and Wellness (Authors are ordered by alphabetic order of surname). The authors gratefully acknowledge the surname review panel members of Thu Ha Nguyen and Siu Yu, and valuable comments from Yan Jin and Shaun Malo of Alberta Health & Wellness. They also thank Dr. Carolyn De Coster who helped with the writing and editing of the report. Thanks to Fraser Noseworthy for assisting with the cover page design. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Chinese surname list to define Chinese ethnicity was developed through literature review, a panel review, and a telephone survey of a randomly selected sample in Calgary. It was validated with the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Results show that the proportion who self-reported as Chinese has high agreement with the proportion identified by the surname list in the CCHS. The surname list was applied to the Alberta Health Insurance Plan registry database to define the Chinese ethnic population, and to the Vital Statistics Death Registry to assess the Chinese ethnic population mortality in Alberta. -

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Yurou Zhong All rights reserved ABSTRACT Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Yurou Zhong This dissertation examines the modern Chinese script crisis in twentieth-century China. It situates the Chinese script crisis within the modern phenomenon of phonocentrism – the systematic privileging of speech over writing. It depicts the Chinese experience as an integral part of a worldwide crisis of non-alphabetic scripts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It places the crisis of Chinese characters at the center of the making of modern Chinese language, literature, and culture. It investigates how the script crisis and the ensuing script revolution intersect with significant historical processes such as the Chinese engagement in the two World Wars, national and international education movements, the Communist revolution, and national salvation. Since the late nineteenth century, the Chinese writing system began to be targeted as the roadblock to literacy, science and democracy. Chinese and foreign scholars took the abolition of Chinese script to be the condition of modernity. A script revolution was launched as the Chinese response to the script crisis. This dissertation traces the beginning of the crisis to 1916, when Chao Yuen Ren published his English article “The Problem of the Chinese Language,” sweeping away all theoretical oppositions to alphabetizing the Chinese script. This was followed by two major movements dedicated to the task of eradicating Chinese characters: First, the Chinese Romanization Movement spearheaded by a group of Chinese and international scholars which was quickly endorsed by the Guomingdang (GMD) Nationalist government in the 1920s; Second, the dissident Chinese Latinization Movement initiated in the Soviet Union and championed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the 1930s.