Opening Remarks Guo Changgang: Good Morning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chieftains Into Ancestors: Imperial Expansion and Indigenous Society in Southwest China

1 Chieftains into Ancestors: Imperial Expansion and Indigenous Society in Southwest China. David Faure and Ho Ts’ui-p’ing, editors. Vancouver and Toronto: University of British Columbia Press, 2013. ISBN: 9780774823692 The scholars whose essays appear in this volume all attempt, in one way or another, to provide a history of southern and southwestern China from the perspective of the people who lived and still live there. One of the driving forces behind the impressive span of research across several cultural and geographical areas is to produce or recover the history(ies) of indigenous conquered people as they saw and experienced it, rather than from the perspective of the Chinese imperial state. It is a bold and fresh look at a part of China that has had a long-contested relationship with the imperial center. The essays in this volume are all based on extensive fieldwork in places ranging from western Yunnan to western Hunan to Hainan Island. Adding to the level of interest in these pieces is the fact that these scholars also engage with imperial-era written texts, as they interrogate the different narratives found in oral (described as “ephemeral”) rituals and texts written in Chinese. In fact, it is precisely the nexus or difference between these two modes of communicating the past and the relationship between the local and the central state that energizes all of the scholarship presented in this collection of essays. They bring a very different understanding of how the Chinese state expanded its reach over this wide swath of territory, sometimes with the cooperation of indigenous groups, sometimes in stark opposition, and how indigenous local traditions were, and continue to be, reified and constructed in ways that make sense of the process of state building from local perspectives. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

SSA1208 / GES1005 – Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past and Present

SSA1208 / GES1005 – Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past and Present Group Essay Ho Lim Keng Temple Prepared By: Tutorial [D5] Chew Si Hui (A0130382R) Kwek Yee Ying (A0130679Y) Lye Pei Xuan (A0146673X) Soh Rolynn (A0130650W) Submission Date: 31th March 2017 1 Content Page 1. Introduction to Ho Lim Keng Temple 3 2. Exterior & Courtyard 3 3. Second Level 3 4. Interior & Main Hall 4 5. Main Gods 4 6. Secondary Gods 5 7. Our Views 6 8. Experiences Encountered during our Temple Visit 7 9. References 8 10. Appendix 8 2 1. Introduction to Ho Lim Keng Temple Ho Lim Keng Temple is a Taoist temple and is managed by common surname association, Xu (许) Clan. Chinese clan associations are benevolent organizations of popular origin found among overseas Chinese communities for individuals with the same surname. This social practice arose several centuries ago in China. As its old location was acquisited by the government for redevelopment plans, they had moved to a new location on Outram Hill. Under the leadership of 许木泰宗长 and other leaders, along with the clan's enthusiastic response, the clan managed to raise a total of more than $124,000, and attained their fundraising goal for the reconstruction of the temple. Reconstruction works commenced in 1973 and was completed in 1975. Ho Lim Keng Temple was advocated by the Xu Clan in 1961, with a board of directors to manage internal affairs. In 1966, Ho Lim Keng Temple applied to the Registrar of Societies and was approved on February 28, 1967 and then was published in the Government Gazette on March 3. -

Or Bis Book S

Spring 2017 Pope Francis WITH THE SMELL OF THE SHEEP See Page 3 Orbis Books A World of Books That Matter Maryknoll, NY 800.258.5838 ORBISBOOKS.COM MORNING HOMILIES IV Pope Francis “Each morning since Pope Francis’s election, I have read his beautiful morning homilies . These homilies—clear, brief, often funny and always grounded in experience, are my favorite of all the pope’s talks and writings. It never fails to astonish how Pope Francis can find something new in these familiar Bible passages, and I hope that his sur- prising insights will lead you deeper into Scripture and help you encounter God in a new way." —James Martin, SJ, author, Jesus: A Pilgrimage ach day Pope Francis says Mass and offers a short homily for fellow residents and Eguests in the chapel of St. Martha’s Guest- house, where he has chosen to live. Through these accounts of his morning homilies, drawn from July to November 2014, it is now possible for those who were not present to experience and enjoy his lively manner of speaking, and his capacity to engage his listeners and their daily lives with the joy of the gospel message. APRIL 3 192pp., 5 /8 x 8¼ $18 softcover ISBN 978-1-62698-228-4 RELIGION/Christianity/Catholic RELIGION/Sermons/Christian MORE MORNING HOMILIES MORNING HOMILIES I MORNING HOMILIES II MORNING HOMILIES III (MAR.-AUG. 2013) (SEP. 2013-JAN. 2014) (FEB.-JUN. 2014) ISBN 978-1-62698-111-9 ISBN 978-1-62698-179-9 ISBN 978-1-62698-147-8 $18 softcover $18 softcover $18 softcover Dear Friends, When Orbis first launched our Modern Spiritual MORNING HOMILIES IV Masters Series twenty years ago, the “masters” were Pope Francis mostly historical figures. -

Currents Fall 2009

fb_fall 09 currents2_!!GTU_Currents Redesign Draft 2 10/8/09 2:51 PM Page 1 GTU Where religion meets the world news of the G raduate t heoloGical u nion fall 2009 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: 2 A Prophetic Voice on Social Justice 4 Finding Slavery in Your Own Back Yard 5 A-twitter with American Buddhist Monk Heng Sure 9 The Gift Always Comes Back 10 News The Moan 11 New Books and the Shout James Noel on African American Religious Experience Background: “Continuity,” painted by James Noel ake a black sermon, print it in a book, then read it, and you have no idea what it means because it has been abstracted from the living worship of the black church, says T the Rev. Dr. James Noel, (Ph.D. ’99), Farlough Professor of African American Christianity at the San Francisco Theological Seminary. The sermon’s meaning, he says, is deter - mined by the hymns sung, the testimonials, the prayers said before and after the sermon’s deliv - ery, as well as what went on that week for parishioners. Coltrane “My fascination is with religious experience and its various modes of expression,” he says, “espe - “ cially African American religious experience, which is different than that of Europeans or white and the church Americans. The disciplines generated by both the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment — it’s the same aren’t adequate for elucidating black religion, and this has implications for theological education.” thing. Noel’s holistic view of African American religious experience and expression is reflected in his own life. -

The Contemporary Confucian-Christian Encounter: Interreligious Or Intrareligious Dialogue?*

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Publications Humanities January 1995 The onC temporary Confucian-Christian Encounter: Interreligious or Intrareligious Dialogue Christian Jochim San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/humanities_pub Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Christian Jochim. "The onC temporary Confucian-Christian Encounter: Interreligious or Intrareligious Dialogue" Journal of Ecumenical Studies (1995): 35-62. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 32:1, Winter 1995 THE CONTEMPORARY CONFUCIAN-CHRISTIAN ENCOUNTER: INTERRELIGIOUS OR INTRARELIGIOUS DIALOGUE?* Christian Jochim PRECIS The discipline of comparative religions has paid little attention to perhaps the most important religious phenomenon of the late twentieth century: interreligious dialogue. Avail able scholarship on this topic is largely written by and for participants in various dialogues. This scholarship is mainly on the normative issues that concern participants, thus leaving the need for descriptive, analytical scholarship largely unfilled. This essay engages in descriptive analysis of a relatively new twentieth-century dialogue— the Confucian-Christian dialogue —which, nevertheless, has deep historical roots. The essay turns, first, to history, summarizing two different periods of past Confucian-Christian en counter: the period from Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) to the World's Parliament of Religions (1893), and the twentieth-century period leading up to the recent international Confucian- Christian conferences. It turns, second, to the specific nature of the first, second, and third international Confucian-Christian international conferences (1988,1991, and 1994). -

Many Yet One?

Many yet One? MANY YET ONE? Multiple Religious Belonging Edited by Peniel Jesudason Rufus Rajkumar and Joseph Prabhakar Dayam MANY YET ONE? Multiple Religious Belonging Edited by Peniel Jesudason Rufus Rajkumar and Joseph Prabhakar Dayam Copyright © 2016 WCC Publications. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in notices or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: pub- lications@wcc-coe. org. WCC Publications is the book publishing programme of the World Council of Churches. Founded in 1948, the WCC promotes Christian unity in faith, witness and service for a just and peaceful world. A global fellowship, the WCC brings together 345 Protestant, Or- thodox, Anglican and other churches representing more than 550 million Christians in 110 countries and works cooperatively with the Roman Catholic Church. Opinions expressed in WCC Publications are those of the authors. Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, © copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Cover design: Adele Robey, Phoenix Graphics, Inc. Book design and typesetting: Michelle Cook / 4 Seasons Book Design ISBN: 978-2-8254-1669-3 World Council of Churches 150 route de Ferney, P. O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland http://publications. oikoumene. org CONTENTS Contributors vii Introduction Peniel Jesudason Rufus Rajkumar and 1 Joseph Prabhakar Dayam 1. Eucharist Upstairs, Yoga Downstairs: On Multiple 5 Religious Participation John J. Thatamanil 2. On Doing as Others Do: Theological Perspectives 27 on Multiple Religious Practice S. -

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China Noga Ganany Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Noga Ganany All rights reserved ABSTRACT Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late Ming China Noga Ganany In this dissertation, I examine a genre of commercially-published, illustrated hagiographical books. Recounting the life stories of some of China’s most beloved cultural icons, from Confucius to Guanyin, I term these hagiographical books “origin narratives” (chushen zhuan 出身傳). Weaving a plethora of legends and ritual traditions into the new “vernacular” xiaoshuo format, origin narratives offered comprehensive portrayals of gods, sages, and immortals in narrative form, and were marketed to a general, lay readership. Their narratives were often accompanied by additional materials (or “paratexts”), such as worship manuals, advertisements for temples, and messages from the gods themselves, that reveal the intimate connection of these books to contemporaneous cultic reverence of their protagonists. The content and composition of origin narratives reflect the extensive range of possibilities of late-Ming xiaoshuo narrative writing, challenging our understanding of reading. I argue that origin narratives functioned as entertaining and informative encyclopedic sourcebooks that consolidated all knowledge about their protagonists, from their hagiographies to their ritual traditions. Origin narratives also alert us to the hagiographical substrate in late-imperial literature and religious practice, wherein widely-revered figures played multiple roles in the culture. The reverence of these cultural icons was constructed through the relationship between what I call the Three Ps: their personas (and life stories), the practices surrounding their lore, and the places associated with them (or “sacred geographies”). -

The Heart of Policy

currents GTU NEWS OF THE G RADUATE T HEOLOGICAL U NION Where religion meets the world Spring 2006 what’s inside The Heart of Policy 3 Opening a Conversation “ t’s not that I’m advocating war, but there are cases where military force might 4 Bonnie Hardwick Looks Ibe necessary, and we’d better have a rational or ethical way to decide whether Back–and Forward it’s just or not.” 5 Adams Receives Sarlo Award Military intervention may not seem an intuitive area of study for the seminary, but for 2006 GTU doctoral graduate, lawyer, and mother Eileen Chamberlain 7 A Greater Effect for Good of Portola Valley, California, there is no incongruity. “My concern, which flows 10 Point of View: out of the moral concern, is that our current norms on using force can’t be Christian Mission squared necessarily within an ethical framework, and I’m trying to bring them into that framework.” Eileen Chamberlain, 12 News and Notes Ph.D. ’06 13 Commencement In her dissertation, Humanitarian Military Intervention: The Moral Imperative Versus the Rule of Law, Chamberlain examines both the ethical and legal justifications for using peacekeeping forces. She points out an egregious disconnect between theory and reality that undermines the rule of law and makes humanitarian policy less effective. Focusing her work ended up being “as simple as reading the newspaper. I just followed what seemed to matter to me,” she said. “I’ve always been interested in international law, and have done human rights work. When I first came to the Graduate Theological Union I had no idea that I would write about this, but the topic really brought together my passions.” A lawyer who had taken a hiatus when her third of four children was born, Chamberlain chose the GTU to I started“ with the follow a deeper calling. -

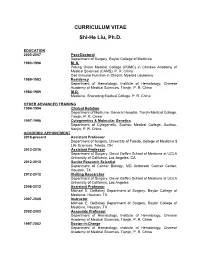

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D. EDUCATION 2003-2007 Post-Doctoral Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine 1993-1996 M. S. Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS). P. R. China Cell Immune Function in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia 1989-1993 Residency Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1984-1989 M.D. Medicine, Shandong Medical College, P. R. China OTHER ADVANCED TRAINING 1994-1994 Clinical Rotation Department of Medicine, General Hospital, Tianjin Medical College, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-1998 Cytogenetics & Molecular Genetics Department of Cytogenetic, Suzhou Medical College, Suzhou, Nanjin, P. R. China ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT 2016-present Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, University of Toledo, College of Medicine $ Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 2013-2016 Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles, CA 2012-2013 Senior Research Scientist Department of Cancer Biology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 2012-2012 Visiting Researcher Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles 2008-2012 Assistant Professor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2007-2008 Instructor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2002-2003 Associate Professor Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-2002 Doctor-in-Charge Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China HONORS OR AWARDS 2015 Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research award. -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Xi Jinping's Inner Circle (Part 2: Friends from Xi's Formative Years)

Xi Jinping’s Inner Circle (Part 2: Friends from Xi’s Formative Years) Cheng Li The dominance of Jiang Zemin’s political allies in the current Politburo Standing Committee has enabled Xi Jinping, who is a protégé of Jiang, to pursue an ambitious reform agenda during his first term. The effectiveness of Xi’s policies and the political legacy of his leadership, however, will depend significantly on the political positioning of Xi’s own protégés, both now and during his second term. The second article in this series examines Xi’s longtime friends—the political confidants Xi met during his formative years, and to whom he has remained close over the past several decades. For Xi, these friends are more trustworthy than political allies whose bonds with Xi were built primarily on shared factional association. Some of these confidants will likely play crucial roles in helping Xi handle the daunting challenges of the future (and may already be helping him now). An analysis of Xi’s most trusted associates will not only identify some of the rising stars in the next round of leadership turnover in China, but will also help characterize the political orientation and worldview of the influential figures in Xi’s most trusted inner circle. “Who are our enemies? Who are our friends?” In the early years of the Chinese Communist movement, Mao Zedong considered this “a question of first importance for the revolution.” 1 This question may be even more consequential today, for Xi Jinping, China’s new top leader, than at any other time in the past three decades.