Chieftains Into Ancestors: Imperial Expansion and Indigenous Society in Southwest China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narrative Inquiry Into Chinese International Doctoral Students

Volume 16, 2021 NARRATIVE INQUIRY INTO CHINESE INTERNATIONAL DOCTORAL STUDENTS’ JOURNEY: A STRENGTH-BASED PERSPECTIVE Shihua Brazill Montana State University, Bozeman, [email protected] MT, USA ABSTRACT Aim/Purpose This narrative inquiry study uses a strength-based approach to study the cross- cultural socialization journey of Chinese international doctoral students at a U.S. Land Grant university. Historically, we thought of socialization as an institu- tional or group-defined process, but “journey” taps into a rich narrative tradi- tion about individuals, how they relate to others, and the identities that they carry and develop. Background To date, research has employed a deficit perspective to study how Chinese stu- dents must adapt to their new environment. Instead, my original contribution is using narrative inquiry study to explore cross-cultural socialization and mentor- ing practices that are consonant with the cultural capital that Chinese interna- tional doctoral students bring with them. Methodology This qualitative research uses narrative inquiry to capture and understand the experiences of three Chinese international doctoral students at a Land Grant in- stitute in the U.S. Contribution This study will be especially important for administrators and faculty striving to create more diverse, supportive, and inclusive academic environments to en- hance Chinese international doctoral students’ experiences in the U.S. Moreo- ver, this study fills a gap in existing research by using a strength-based lens to provide valuable practical insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymak- ers to support the unique cross-cultural socialization of Chinese international doctoral students. Findings Using multiple conversational interviews, artifacts, and vignettes, the study sought to understand the doctoral experience of Chinese international students’ experience at an American Land Grant University. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

THE UNIVERSITY of BRITISH COLUMBIA Curriculum Vitae for Faculty Members

THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Curriculum Vitae for Faculty Members Date: April 20, 2019 Initials:NN 1. SURNAME:Nan FIRST NAME:Ning MIDDLE NAME(S): 2. DEPARTMENT/SCHOOL:Accounting and Information Systems 3. FACULTY:Sauder School of Business 4. PRESENT RANK:Assistant Professor SINCE:June 2012 5. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates University of Michigan PhD1 Business Administration August, 2006 University of Minnesota MA Mass Communication July, 2002 Peking University BA Advertising July, 1999 Special Professional Qualifications 6. EMPLOYMENT RECORD (a) Prior to coming to UBC University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates University of Oklahoma Assistant Professor 2006-2012 (b) At UBC Rank or Title Dates Assistant Professor 2012-present (c) Date of granting of tenure at U.B.C.: 1 Title of Dissertation: Unintended Consequences in Central-Remote Office Arrangement: A Study Coupling Laboratory Experiments with Multi-Agent Modeling. Supervisor: Prof. Judith Olson Updated April 20, 2019 - Page 2/15 7. LEAVES OF ABSENCE University, Company or Organization Type of Leave Dates at which Leave was taken 8. TEACHING (a) Areas of special interest and accomplishments My teaching experience includes undergraduate, MBA, and PhD level courses. I seek to deliver both handson technology skills and critical thinking abilities to students. To date, I have taught the following topics: • E-business (digital business) • Database management • Introduction to Management Information Systems • Complexity theory -

SSA1208 / GES1005 – Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past and Present

SSA1208 / GES1005 – Everyday Life of Chinese Singaporeans: Past and Present Group Essay Ho Lim Keng Temple Prepared By: Tutorial [D5] Chew Si Hui (A0130382R) Kwek Yee Ying (A0130679Y) Lye Pei Xuan (A0146673X) Soh Rolynn (A0130650W) Submission Date: 31th March 2017 1 Content Page 1. Introduction to Ho Lim Keng Temple 3 2. Exterior & Courtyard 3 3. Second Level 3 4. Interior & Main Hall 4 5. Main Gods 4 6. Secondary Gods 5 7. Our Views 6 8. Experiences Encountered during our Temple Visit 7 9. References 8 10. Appendix 8 2 1. Introduction to Ho Lim Keng Temple Ho Lim Keng Temple is a Taoist temple and is managed by common surname association, Xu (许) Clan. Chinese clan associations are benevolent organizations of popular origin found among overseas Chinese communities for individuals with the same surname. This social practice arose several centuries ago in China. As its old location was acquisited by the government for redevelopment plans, they had moved to a new location on Outram Hill. Under the leadership of 许木泰宗长 and other leaders, along with the clan's enthusiastic response, the clan managed to raise a total of more than $124,000, and attained their fundraising goal for the reconstruction of the temple. Reconstruction works commenced in 1973 and was completed in 1975. Ho Lim Keng Temple was advocated by the Xu Clan in 1961, with a board of directors to manage internal affairs. In 1966, Ho Lim Keng Temple applied to the Registrar of Societies and was approved on February 28, 1967 and then was published in the Government Gazette on March 3. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

Self-Study Syllabus on Chinese Foreign Policy

Self-Study Syllabus on Chinese Foreign Policy www.mandarinsociety.org PrefaceAbout this syllabus with China’s rapid economic policymakers in Washington, Tokyo, Canberra as the scale and scope of China’s current growth, increasing military and other capitals think about responding to involvement in Africa, China’s first overseas power,Along and expanding influence, Chinese the challenge of China’s rising power. military facility in Djibouti, or Beijing’s foreign policy is becoming a more salient establishment of the Asian Infrastructure concern for the United States, its allies This syllabus is organized to build Investment Bank (AIIB). One of the challenges and partners, and other countries in Asia understanding of Chinese foreign policy in that this has created for observers of China’s and around the world. As China’s interests a step-by-step fashion based on one hour foreign policy is that so much is going on become increasingly global, China is of reading five nights a week for four weeks. every day it is no longer possible to find transitioning from a foreign policy that was In total, the key readings add up to roughly one book on Chinese foreign policy that once concerned principally with dealing 800 pages, rarely more than 40–50 pages will provide a clear-eyed assessment of with the superpowers, protecting China’s for a night. We assume no prior knowledge everything that a China analyst should know. regional interests, and positioning China of Chinese foreign policy, only an interest in as a champion of developing countries, to developing a clearer sense of how China is To understanding China’s diplomatic history one with a more varied and global agenda. -

Opening Remarks Guo Changgang: Good Morning

Opening Remarks Guo Changgang: Good morning. Let’s start our workshop. First, I want to say many, many thanks to our dear guests and colleagues who took their time to participate in this event. And I should also firstly thank Professor Mark Juergensmeyer. Actually, he had this idea when we met last year in Chicago, where we talked about it. In recent years, my field and my interest is in religion and its’ globalizing force, the role of religion and its’ globalizing force in some specific religious countries; the role of religion and also the tension between religion and nation-states. So when we talked together, we came to this idea to make this joint event. So I should thank Mark Juergensmeyer actually for making this event possible. And also thanks to Dinah. Dinah, you actually give a big support to Mark Juergensmeyer’s project. Guo Changgang: Now I’d like to introduce our colleagues and every participant. Professor Tajima Tadaatsu. Oh, Tadaatsu Tajima. Can we just call you Tad? He is a professor from Tenshi College, Japan. Dr. Greg Auberry from Catholic Relief Services, Center in Cambodia. Professor Zhang Zhigang, he is still on the way he is a Professor from Peking University. He’s still on the way up here. Professor David A. Palmer from Hong Kong University. I think your field is Taoism. Chinese religion and Taoism, and director She Hongye from the Amity Foundation. Dr. Victor from UCSB center of Santa Barbara and colleague to Mark. Mark Juergensmeyer : More than a colleague. He is my right hand man. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China Noga Ganany Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Noga Ganany All rights reserved ABSTRACT Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late Ming China Noga Ganany In this dissertation, I examine a genre of commercially-published, illustrated hagiographical books. Recounting the life stories of some of China’s most beloved cultural icons, from Confucius to Guanyin, I term these hagiographical books “origin narratives” (chushen zhuan 出身傳). Weaving a plethora of legends and ritual traditions into the new “vernacular” xiaoshuo format, origin narratives offered comprehensive portrayals of gods, sages, and immortals in narrative form, and were marketed to a general, lay readership. Their narratives were often accompanied by additional materials (or “paratexts”), such as worship manuals, advertisements for temples, and messages from the gods themselves, that reveal the intimate connection of these books to contemporaneous cultic reverence of their protagonists. The content and composition of origin narratives reflect the extensive range of possibilities of late-Ming xiaoshuo narrative writing, challenging our understanding of reading. I argue that origin narratives functioned as entertaining and informative encyclopedic sourcebooks that consolidated all knowledge about their protagonists, from their hagiographies to their ritual traditions. Origin narratives also alert us to the hagiographical substrate in late-imperial literature and religious practice, wherein widely-revered figures played multiple roles in the culture. The reverence of these cultural icons was constructed through the relationship between what I call the Three Ps: their personas (and life stories), the practices surrounding their lore, and the places associated with them (or “sacred geographies”). -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

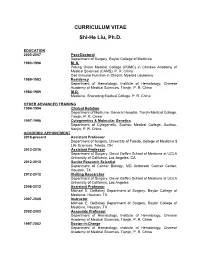

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Shi-He Liu, Ph.D. EDUCATION 2003-2007 Post-Doctoral Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine 1993-1996 M. S. Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS). P. R. China Cell Immune Function in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia 1989-1993 Residency Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1984-1989 M.D. Medicine, Shandong Medical College, P. R. China OTHER ADVANCED TRAINING 1994-1994 Clinical Rotation Department of Medicine, General Hospital, Tianjin Medical College, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-1998 Cytogenetics & Molecular Genetics Department of Cytogenetic, Suzhou Medical College, Suzhou, Nanjin, P. R. China ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT 2016-present Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, University of Toledo, College of Medicine $ Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 2013-2016 Assistant Professor Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles, CA 2012-2013 Senior Research Scientist Department of Cancer Biology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 2012-2012 Visiting Researcher Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA University of California, Los Angeles 2008-2012 Assistant Professor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2007-2008 Instructor Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 2002-2003 Associate Professor Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China 1997-2002 Doctor-in-Charge Department of Hematology, Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Tianjin, P. R. China HONORS OR AWARDS 2015 Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research award. -

Howard on Qiang, 'Art, Religion and Politics in Medieval China: the Dunhuang Cave of the Zhai Family'

H-Asia Howard on Qiang, 'Art, Religion and Politics in Medieval China: The Dunhuang Cave of the Zhai Family' Review published on Sunday, January 1, 2006 Ning Qiang. Art, Religion and Politics in Medieval China: The Dunhuang Cave of the Zhai Family. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004. xv + 178 pp. $39.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8248-2703-8. Reviewed by Angela Howard (Rutgers,) Published on H-Asia (January, 2006) The Making of a Seventh-Century Buddhist Cave in Dunhuang, China: Politics or Piety This book is a case study of Dunhuang Cave 220, completed in 642 through the sponsorship of the prominent Zhai family, which continued to supervise the cave's upkeep until the tenth century. Ning Qiang has chosen the cave for several reasons; it is dated, we know the identity of its patrons, and its décor manifests stylistic and doctrinal innovations. Breaking away from sixth-century stylistic and doctrinal conventions, Cave 220 was decorated with large murals of Pure Lands or Paradises on the lateral walls, a composition of the Vimalakirti and Manjushri (the Bodhisattva of Wisdom) debate above the entrance, and a large niche in the rear wall where a group of sculpture was complemented by painted images on the niche's surrounding walls. The lay-out and décor established a model for subsequent Tang caves. Although the author emphatically states that his study gives equal weight to the textual sources of the décor, related pictorial examples, and their socio-political foundations, he emphasizes the political and social influence of patronage and tends to overlook the religious sources of the art.