General Introduction Part One Medieval Russia: Kiev to Moscow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meat: a Novel

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 2019 Meat: A Novel Sergey Belyaev Boris Pilnyak Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Belyaev, Sergey; Pilnyak, Boris; and LeBlanc, Ronald D., "Meat: A Novel" (2019). Faculty Publications. 650. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/650 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sergey Belyaev and Boris Pilnyak Meat: A Novel Translated by Ronald D. LeBlanc Table of Contents Acknowledgments . III Note on Translation & Transliteration . IV Meat: A Novel: Text and Context . V Meat: A Novel: Part I . 1 Meat: A Novel: Part II . 56 Meat: A Novel: Part III . 98 Memorandum from the Authors . 157 II Acknowledgments I wish to thank the several friends and colleagues who provided me with assistance, advice, and support during the course of my work on this translation project, especially those who helped me to identify some of the exotic culinary items that are mentioned in the opening section of Part I. They include Lynn Visson, Darra Goldstein, Joyce Toomre, and Viktor Konstantinovich Lanchikov. Valuable translation help with tricky grammatical constructions and idiomatic expressions was provided by Dwight and Liya Roesch, both while they were in Moscow serving as interpreters for the State Department and since their return stateside. -

Revolution in Real Time: the Russian Provisional Government, 1917

ODUMUNC 2020 Crisis Brief Revolution in Real Time: The Russian Provisional Government, 1917 ODU Model United Nations Society Introduction seventy-four years later. The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to be keenly felt The Russian Revolution began on 8 March 1917 to this day. with a series of public protests in Petrograd, then the Winter Capital of Russia. These protests But could it have gone differently? Historians lasted for eight days and eventually resulted in emphasize the contingency of events. Although the collapse of the Russian monarchy, the rule of history often seems inventible afterwards, it Tsar Nicholas II. The number of killed and always was anything but certain. Changes in injured in clashes with the police and policy choices, in the outcome of events, government troops in the initial uprising in different players and different accidents, lead to Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people. surprising outcomes. Something like the Russian Revolution was extremely likely in 1917—the The collapse of the Romanov dynasty ushered a Romanov Dynasty was unable to cope with the tumultuous and violent series of events, enormous stresses facing the country—but the culminating in the Bolshevik Party’s seizure of revolution itself could have ended very control in November 1917 and creation of the differently. Soviet Union. The revolution saw some of the most dramatic and dangerous political events the Major questions surround the Provisional world has ever known. It would affect much Government that struggled to manage the chaos more than Russia and the ethnic republics Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. -

The Education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov The

Agata Strzelczyk DOI: 10.14746/bhw.2017.36.8 Department of History Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Abstract This article concerns two very different ways and methods of upbringing of two Russian tsars – Alexander the First and Nicholas the First. Although they were brothers, one was born nearly twen- ty years before the second and that influenced their future. Alexander, born in 1777 was the first son of the successor to the throne and was raised from the beginning as the future ruler. The person who shaped his education the most was his grandmother, empress Catherine the Second. She appoint- ed the Swiss philosopher La Harpe as his teacher and wanted Alexander to become the enlightened monarch. Nicholas, on the other hand, was never meant to rule and was never prepared for it. He was born is 1796 as the ninth child and third son and by the will of his parents, Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Fyodorovna he received education more suitable for a soldier than a tsar, but he eventually as- cended to the throne after Alexander died. One may ask how these differences influenced them and how they shaped their personalities as people and as rulers. Keywords: Romanov Children, Alexander I and Nicholas I, education, upbringing The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Among the ten children of Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, two sons – the oldest Alexander and Nicholas, the second youngest son – took the Russian throne. These two brothers and two rulers differed in many respects, from their characters, through poli- tics, views on Russia’s place in Europe, to circumstances surrounding their reign. -

Raisa Gorbacheva, the Soviet Union’S Only First Lady

Outraging the People by Stepping out of the Shadows Gender roles, the ‘feminine ideal’ and gender discourse in the Soviet Union and Raisa Gorbacheva, the Soviet Union’s only First Lady. Noraly Terbijhe Master Thesis MA Russian & Eurasian Studies Leiden University January 2020, Leiden Everywhere in the civilised world, the position, the rights and obligations of a wife of the head of state are more or less determined. For instance, I found out that the President’s wife in the White House has special staff to assist her in preforming her duties. She even has her own ‘territory’ and office in one wing of the White House. As it turns out, I as the First Lady had only one tradition to be proud of, the lack of any right to an official public existence.1 Raisa Maximovna Gorbacheva (1991) 1 Translated into English from Russian. From: Raisa Gorbacheva, Ya Nadeyus’ (Moscow 1991) 162. 1 Table of contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Literature review ........................................................................................................................... 9 3. Gender roles and discourse in Russia and the USSR ................................................................. 17 The supportive comrade ................................................................................................................. 19 The hardworking mother ............................................................................................................... -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Bulletin 10-Final Cover

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN Issue 10 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. March 1998 Leadership Transition in a Fractured Bloc Featuring: CPSU Plenums; Post-Stalin Succession Struggle and the Crisis in East Germany; Stalin and the Soviet- Yugoslav Split; Deng Xiaoping and Sino-Soviet Relations; The End of the Cold War: A Preview COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 10 The Cold War International History Project EDITOR: DAVID WOLFF CO-EDITOR: CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN ADVISING EDITOR: JAMES G. HERSHBERG ASSISTANT EDITOR: CHRISTA SHEEHAN MATTHEW RESEARCH ASSISTANT: ANDREW GRAUER Special thanks to: Benjamin Aldrich-Moodie, Tom Blanton, Monika Borbely, David Bortnik, Malcolm Byrne, Nedialka Douptcheva, Johanna Felcser, Drew Gilbert, Christiaan Hetzner, Kevin Krogman, John Martinez, Daniel Rozas, Natasha Shur, Aleksandra Szczepanowska, Robert Wampler, Vladislav Zubok. The Cold War International History Project was established at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., in 1991 with the help of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and receives major support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Smith Richardson Foundation. The Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to disseminate new information and perspectives on Cold War history emerging from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side”—the former Communist bloc—through publications, fellowships, and scholarly meetings and conferences. Within the Wilson Center, CWIHP is under the Division of International Studies, headed by Dr. Robert S. Litwak. The Director of the Cold War International History Project is Dr. David Wolff, and the incoming Acting Director is Christian F. -

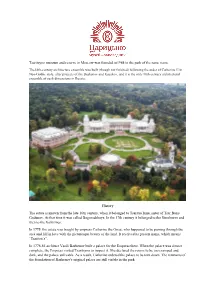

Tsaritsyno Museum and Reserve in Moscow Was Founded In1984 in the Park of the Same Name

Tsaritsyno museum and reserve in Moscow was founded in1984 in the park of the same name. The18th-century architecture ensemble was built (though not finished) following the order of Catherine II in Neo-Gothic style, after projects of the Bazhenov and Kazakov, and it is the only 18th-century architectural ensemble of such dimensions in Russia. History The estate is known from the late 16th century, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. At that time it was called Bogorodskoye. In the 17th century it belonged to the Streshnevs and then to the Galitzines. In 1775, the estate was bought by empress Catherine the Great, who happened to be passing through the area and fell in love with the picturesque beauty of the land. It received its present name, which means “Tsaritsa’s”. In 1776-85 architect Vasili Bazhenov built a palace for the Empress there. When the palace was almost complete, the Empress visited Tsaritsyno to inspect it. She declared the rooms to be too cramped and dark, and the palace unlivable. As a result, Catherine ordered the palace to be torn down. The remnants of the foundation of Bazhenov's original palace are still visible in the park. In 1786, Matvey Kazakov presented new architectural plans, which were approved by Catherine. Kazakov supervised the construction project until 1796 when the construction was interrupted by Catherine's death. Her successor, Emperor Paul I of Russia showed no interest in the palace and the massive structure remained unfinished and abandoned for more than 200 years, until it was completed and extensively reworked in 2005-07. -

1 December 2018 SHEILA M. PUFFER University Distinguished

December 2018 SHEILA M. PUFFER University Distinguished Professor Professor of International Business and Strategy International Business and Strategy Group D’Amore-McKim School of Business Northeastern University, Boston, USA CONTACT INFORMATION 313 Hayden Hall, Northeastern University, 360 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Business Administration, University of California, Berkeley Diploma in Management, Plekhanov Institute of the National Economy, Moscow, Russia M.B.A., University of Ottawa, Canada B.A., Slavic Studies, University of Ottawa POSITIONS HELD 1988 - present University Distinguished Professor (2011 – present) Professor of International Business and Strategy D’Amore-McKim School of Business, Northeastern University 1990 – present Fellow, Davis Center for Russian Studies, Harvard University 2018 – present Faculty Affiliate, Global Resilience Institute, Northeastern University May 2019 Fellow, Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia, New York University Jan. - Sept. 2015 Visiting Scholar, Stanford University Graduate School of Business 2007 – 2012 Cherry Family Senior Fellow of International Business, Northeastern University April 2012 Visiting Professor, University of Nottingham Business School, Ningbo, China February 2012 Visiting Professor, IEDC Business School doctoral program, Bled, Slovenia April 2009 Visiting Professor, Stockholm School of Economics July 1996 Visiting Professor, Ecole Supérieure de Commerce, Reims, France (Joint program with Northeastern University) -

Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War Natalia Zemtsova CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/49 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War Natalia Zemtsova May 2011 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York Advisor: Jean Krasno ABSTRACT The role of a political leader has always been important for understanding both domestic and world politics. The most significant historical events are usually associated in our minds with the images of the people who were directly involved and who were in charge of the most crucial decisions at that particular moment in time. Thus, analyzing the American Civil War, we always mention the great role and the achievements of Abraham Lincoln as the president of the United States. We cannot forget about the actions of such charismatic leaders as Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt when we think about the brutal events and the outcome of the World War II. Or, for example, the Cuban Missile Crisis and its peaceful solution went down in history highlighting roles of John F. -

Law and Familial Order in the Romanov Dynasty *

Russian History 37 (2010) 389–411 brill.nl/ruhi “For the Firm Maintenance of the Dignity and Tranquility of the Imperial Family”: Law and Familial Order in the Romanov Dynasty * Russell E. Martin Westminster College Abstract Th is article examines the Law of Succession and the Statute on the Imperial Family, texts which were issued by Emperor Paul I on April 5,1797, and which regulated the succession to the throne and the structure of the Romanov dynasty as a family down to the end of the empire in 1917. It also analyzes the revisions introduced in these texts by subsequent emperors, focusing particu- larly on the development of a requirement for equal marriage and for marrying Orthodox spouses. Th e article argues that changing circumstances in the dynasty—its rapid increase in numbers, its growing demands on the fi nancial resources of the Imperial Household, its struggle to resist morganatic and interfaith marriages—forced changes to provisions in the Law and Statute, and that the Romanovs debated and reformed the structure of the Imperial Family in the context of the provisions of these laws. Th e article shows how these Imperial House laws served as a vitally important arena for reform and legal culture in pre-revolutionary Russia. Keywords Paul I, Alexander III , Fundamental Laws of Russia , Statute on the Imperial Family , Succession , Romanov dynasty Th e death of Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna on the night of May 23-24, 2010, garnered more media coverage in Russia than is typical for members of the Russian Imperial house. As the widow of Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich (1917-1992), the legitimist claimant to the vacant Russian throne (the fi rst * ) I wish to thank the staff of Hillman Library of the University of Pittsburgh, for their assistance to me while working in the stacks on this project, and Connie Davis, the intrepid interlibrary loan administrator of McGill Library at Westminster College, for her time and help fi nding sources for me. -

Georgian Opposition to Soviet Rule (1956-1989) and the Causes of Resentment

Georgian Opposition to Soviet Rule (1956-1989) and the Causes of Resentment between Georgia and Russia Master‘s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lisa Anne Goddard Graduate Program in Slavic and East European Studies The Ohio State University 2011 Master‘s Thesis Committee: Nicholas Breyfogle, Advisor Theodora Dragostinova Irma Murvanishvili Copyright by Lisa Anne Goddard 2011 Abstract This Master‘s thesis seeks to examine the question of strained relations between Georgia and the Russian Federation, paying particular attention to the Georgian revolts of 1956, 1978 and 1989 during the Soviet era. By examining the results of these historical conflicts, one can discern a pattern of three major causes of the tensions between these neighboring peoples: disagreement with Russia over national identity characteristics such as language, disputes over territory, and degradation of symbols of national legacy. It is through conflicts and revolts on the basis of these three factors that Georgian anti- Russian sentiment and Russian anti-Georgian sentiment developed. This thesis is divided into four chapters that will explore the origins and results of each uprising, as well as the evolving conceptions of national identity that served as a backdrop to the conflicts. Following an introduction that lays out the primary questions and findings of the thesis, the second chapter gives a brief history of Georgia and its relationship with Russia, as well as outlines the history and dynamic nature of Georgian national identity. Chapter three, the core chapter, presents the Georgian rebellions during the Soviet era, their causes, and their relevance to this thesis.